1,3-Dibutylimidazolium Chloride: A Down-to-Earth Look

Historical Development

The journey of 1,3-dibutylimidazolium chloride began many decades back, springing from the larger quest to understand ionic liquids and their curious properties. Back in the eighties and nineties, laboratories around the globe started eyeballing imidazolium-based salts for their role in making solvents that shrug off volatility and open new doors in synthetic chemistry. The birth of this molecule marked a clear push toward safer, more stable alternatives in reaction media. Today, the focus is less on chasing the novelty, more on harnessing reliability and moving applications from niche lab settings into larger-scale, real-world uses.

Product Overview

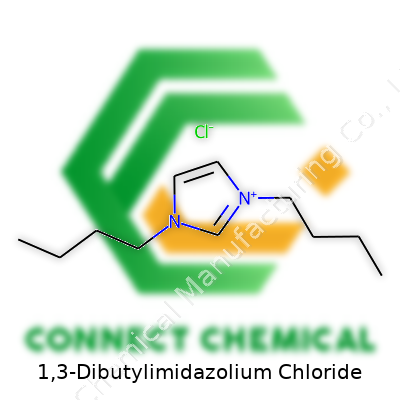

This compound stands out as an ionic liquid, which means it behaves more like a molten salt at room temperature than one would expect. It looks like a pale crystalline solid or sometimes as a viscous fluid, depending on how dry or pure it is. The structure has a bulky imidazole core, padded with two butyl chains and paired up with a chloride ion. This unique blend gives the material a stability that most organic salts miss. Researchers picked this one over others for good reasons: it helps dissolve a stubborn mix of chemicals, works as a mild catalyst, and stays in place under tough conditions.

Physical & Chemical Properties

The melting point typically hovers around 60 to 70°C, although impurities can push it higher or lower. In liquid form, the substance barely has any vapor pressure, making spills less about fumes and more about sticky messes. Its chemical stability under neutral and mildly acidic conditions makes it attractive for projects where water or air would wreck traditional materials. The ionicity means it conducts electricity, sometimes as well as tap water. While many solvents dissolve in it, the real charm comes when mixing polar reagents—few compounds manage to keep everything in solution this well.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Commercial grades usually come with a certificate that reads like a report card—moisture content, chloride purity, and total alkali metals get attention from compliance officers and researchers alike. Labels reflect a focus on safety, highlighting hygroscopic tendencies, sensitivity to strong bases, and storage conditions. A technical data sheet typically lists density at 20°C, which swings near 1.05 g/cm³, and solubility information, including interactions with water, acetone, and common alcohols. Reliable suppliers provide lot numbers and traceability back to batch records.

Preparation Method

The most common route starts with imidazole; perform N-butylation stepwise, then react with an alkyl halide, such as n-butyl chloride, to slip in the needed chains. Next comes a purification sequence—usually re-crystallization and vacuum drying—in order to drive down water and halide impurities. Labs handling it keep a close eye on reaction times and the order of mixing to avoid over-alkylation or side reactions. Increasing demand for quality has pushed chemical manufacturers to adopt more robust purification methods, like counter-current extraction, to crank out more consistent batches.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

This ionic liquid doesn’t just sit around as a solvent; it steps into the ring as a reactant and sometimes a ligand. The imidazolium ring can take part in carbene formations under mild base, leading to catalytic transformations in organic synthesis. There’s a knack for tweaking the butyl chains to nudge solubility or fine-tune viscosity. Chemists experiment with swapping out the chloride for less reactive anions and have used the backbone as a springboard for immobilizing catalysts on solid supports. This kind of tinkering has fueled a steady stream of patents over the last decade.

Synonyms & Product Names

In catalogs and research papers, expect to see alternate names such as 1,3-dibutyl-1H-imidazolium chloride or sometimes DBIM-Cl. It pops up under trade names or abbreviations, yet the backbone stays the same. Clear naming might seem trivial, but anyone who has mixed up similar salts in a reaction run knows why tight labeling keeps troubleshooting from turning into weeks of delays.

Safety & Operational Standards

Safety sheets warn against inhalation and skin contact, which often means gloves and eye protection come out every time the bottle does. This salt likes to absorb water from the air, so storage in tightly sealed containers—sometimes with desiccant packs—becomes standard. Fume hoods cut the risk from airborne particles if you’re heating or stirring it up. On the scale of chemical risk, it behaves better than volatile organics but never as safe as water. Handling protocols align with the push for greener, safer chemistry in industrial and academic settings.

Application Area

This compound shows up everywhere from analytical chemistry labs to pilot-scale organic syntheses. It finds use dissolving cellulosic biomass, separating reaction products, and supporting transition metal catalysts. Electrochemists lean on its conductivity for battery and fuel cell research. In pharmaceuticals, it helps nudge tricky molecules into shape or lures stubborn impurities out of solution. Even in environmental engineering, teams use related salts for pollutant extraction and sensor development. What keeps it in the limelight is flexibility—the same bottle might see use in three different departments in a given week.

Research & Development

Academic journals brim with studies probing solubility, cation effects, and rare reaction pathways. Industrial R&D teams focus on how to cut production costs and control impurities. Whether looking at phase behavior or electrochemical window, investigations aim to tie laboratory discovery to scalable manufacturing. Some researchers push for biodegradable versions, others for salts with a broader temperature range. Conferences buzz with posters and talks about integrating these compounds into solid electrolytes or task-specific solvent blends. Innovation centers on making these materials both greener and cheaper.

Toxicity Research

Toxicology threads run through many of the regulation efforts. Early promise often collided with results showing that, although 1,3-dibutylimidazolium chloride beats volatile solvents for safety, high concentrations can hit aquatic life hard. Studies point to low acute mammalian toxicity but stress that persistence in soils or water might spell trouble. The data urge for responsible disposal and containment in manufacturing—which means scrubbers, containment ponds, and close monitoring around every transfer point. Ongoing work explores how structural tweaks to the imidazolium ring impact environmental fate and breakdown, searching for a way to keep performance without long-term fallout.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, the march toward cleaner chemical processes hinges on finding the right balance between capacity, sustainability, and cost. 1,3-dibutylimidazolium chloride sits at a crossroads of green chemistry and worthwhile performance. Researchers push into energy storage, separation science, and process intensification, using what’s learned from small-batch experiments to design better processes and smarter materials. Industry eyes automation and closed-loop recycling for ionic liquids like this one, to shrink waste and turn costs downward. Every new insight into how these materials work helps bridge the gap between possibility and real improvement in everything from plastics recycling to advanced batteries.

Understanding the Role of 1,3-Dibutylimidazolium Chloride

1,3-Dibutylimidazolium chloride often comes up in technical circles, but for most people, the name means little. This compound falls into the category of ionic liquids, and scientists prize it for its ability to solve tough problems in chemistry and manufacturing. Over the years, I’ve worked with researchers who use materials like this to push boundaries in clean technology and advanced materials.

Industrial Uses and Science in Action

Chemists enjoy working with 1,3-dibutylimidazolium chloride because it behaves differently compared to water or traditional solvents. It can stay liquid at room temperature, carries an ionic charge, and doesn’t evaporate easily. This gives it a distinct advantage in some chemical reactions, especially those that need strict conditions or high efficiency with low waste.

One of the most practical roles for this compound shows up in cellulose processing. Plants produce cellulose, and paper mills or textile factories break it down for pulp or fabric. Regular solvents struggle with tough plant fibers, but ionic liquids handle this job smoothly. I’ve seen these solvents dissolve cellulose far more effectively, opening doors for recycling paper or turning plant leftovers into biofuels and bioplastics.

People working in green chemistry like this compound for another reason—it supports more sustainable manufacturing. By swapping out harsh, toxic chemicals for a safer ionic liquid, factories cut down on pollution and make safer products. The numbers back this up. According to research published in Green Chemistry (2021), ionic liquids, including 1,3-dibutylimidazolium chloride, can shrink the environmental footprint of processing for everything from clothing fibers to pharmaceuticals.

Electrochemistry and Battery Research

With the global push toward electric vehicles and renewable energy, materials science needs advanced electrolytes for cutting-edge batteries. Many regular battery electrolytes break down or catch fire. Researchers are testing ionic liquids as safer alternatives. I met an engineer last year who described small batteries running longer and safer with ionic liquid electrolytes. While 1,3-dibutylimidazolium chloride isn’t the most famous choice yet, its stability and non-flammable nature provide a big advantage over older options.

Lab Workhorses and Specialty Applications

Some applications stay behind the scenes. In academic labs, scientists rely on 1,3-dibutylimidazolium chloride to carry out tough organic and inorganic syntheses. Its ionic nature lets it conduct electricity and shift the way molecules react, and this helps create new compounds, catalysts and potentially life-saving drugs. As someone who’s spent time in experimental labs, I’ve seen the trial and error involved, but also the excitement when a new solvent opens up a reaction pathway previously blocked by older chemicals.

Challenges and Adjustments

The chemical industry has no shortage of hurdles. 1,3-dibutylimidazolium chloride can be expensive to make at large scale and requires careful handling. Companies working on scaling up production often experiment with new synthesis routes or look for ways to recycle and reuse solvents. More accessible production would drive down costs and broaden its use.

Moving Forward

Real progress here comes from teamwork. Universities, companies, and public agencies can pool knowledge to design cleaner, more efficient manufacturing. Laws rewarding pollution reduction or safer chemicals also speed things up. Above all, greater transparency lets experts assess risks and rewards, especially as new data emerges on health and environmental impacts.

Recognizing Its Framework

Chemists often talk about 1,3-dibutylimidazolium chloride as an ionic liquid. I remember learning about these in college and thinking how odd it felt to pour a salt that looked like oil. The secret lives in the molecule's structure. Start with imidazolium—a flat, five-membered ring with two nitrogens. Instead of tiny side groups, it wears two butyl chains, one on each nitrogen. Each butyl chain is a string of four carbon atoms. Those dangly chains help the compound stay gently viscous at room temperature. The chloride comes from a classic sodium-chloride story: an oppositely charged companion that balances everything out.

Why Structure Shapes Behavior

If you ever watch 1,3-dibutylimidazolium chloride on glass, you won't see crystals or grains. You find an oily pool. Its chemical shape explains this—the long butyl groups disrupt tight packing, so the usual brittle solid just never forms. I always found this useful in lab practice because it let us dissolve things regular solvents avoided. For instance, ionic liquids like this tackle cellulose—something water or simple alcohols refused to touch.

This quality leads to green chemistry possibilities. The world pushes hard to replace old fossil fuel-based solvents, many of which evaporate and pollute the air. Ionic liquids resist vaporization and sometimes recycle several times without losing their punch. Their structure, with those fat butyl groups on the imidazolium ring, lets them dissolve plenty of organic and inorganic substances. That makes lab life easier and cuts out some toxic waste streams.

Human Side and Handling

Working with novel chemicals always raises safety flags. Ionic liquids gained a reputation for being safer than volatile organic solvents, but no chemical gets a free pass. I remember my former advisor reminding me to glove up—1,3-dibutylimidazolium chloride won’t give you a headache from fumes, but its long-term health effects demand respect. The structure that keeps it together and in liquid form also means it lingers in water. Labs, factories, and regulatory bodies need to get honest about responsible disposal. Pouring last month’s experiment down the sink feels easy, but the compound might haunt aquatic life if ignored.

Shaping Solutions

There’s a lesson here: structure gives power, but power creates responsibility. I once spent weeks cleaning up ionic liquid residues from failed trials. It drove home the value in planning recycling and waste management right from the start. Europe's REACH regulations push industry toward closed-loop usage, demanding documentation and follow-up. Growing acceptance of green chemistry practices can nudge more scientists and engineers to rethink chemical use at every stage, from beaker to wastewater.

Chemists find themselves at the intersection of old tools and new approaches. The butyl chains, the imidazolium core, that ever-present chloride—together they form something more than a molecular curiosity. They challenge us to weigh benefits and costs, always searching for safer and smarter ways to handle the materials we create.

Everyday Experience Meets Chemical Reality

People working in labs or industries come across chemicals once in a while that bring up questions about safety. 1,3-Dibutylimidazolium chloride isn’t a household name, but it finds its way into research as an ionic liquid. Tucked away in plastic bottles on lab shelves, it claims a spot because of its ability to dissolve a wide range of substances. Even so, safety often takes a back seat during hectic workdays. Thinking a clear liquid looks harmless can lead to problems.

Practical Concerns on Safety

Common sense says don’t trust appearances. Just because 1,3-dibutylimidazolium chloride looks like water doesn’t mean it acts like it. According to published Material Safety Data Sheets, this substance tends to irritate the skin and eyes. A minor splash might not cause blisters, but it can leave a stinging sensation or red skin. Prolonged exposure—through careless spills, dirty gloves, or contaminated work areas—sets the stage for bigger problems, such as chemical burns. Any researcher who’s had a chemical soak into their glove learns fast to never assume a mild liquid poses no threat.

Inhaling fumes is less of a concern since 1,3-dibutylimidazolium chloride comes with low vapor pressure. Though that sounds comforting, accidents involving powders or when the liquid dries can create dust. Those particles, when inhaled, irritate the nose and throat. Research from occupational safety authorities stresses good ventilation around work areas. The old habit of wafting chemical containers to “smell-test” substances doesn’t cut it anymore.

Long Term Health and Environmental Worries

Regulations surrounding 1,3-dibutylimidazolium chloride aren’t as strict as those for cancer-causing chemicals, but scientists study the effects of ionic liquids on people and the planet. There’s evidence that some of these compounds disrupt aquatic organisms even at low concentrations. Pouring them down the drain as if nothing matters puts everyone at risk. Labs that ignore safe disposal rules risk contaminating water streams and violating environmental laws. Better to follow guidelines—even if disposal means extra paperwork or waiting on waste contractors.

Keeping Workplaces Safe

Each person has a part in building a safer culture. Glove use, lab coats, and goggles save skin and eyes every day, and these simple habits stop accidents from turning into bigger stories. Training goes a long way, but real safety grows from watching out for teammates and flagging problems early—a leaky bottle or a missing safety shower only stays a small issue if someone speaks up. Inexperienced students rush through experiments to save time, sometimes skipping PPE. Supervisors and colleagues must keep an eye out, reminding them that taking shortcuts with chemicals never pays off.

What Works: Sensible, Proven Solutions

Years of working with chemicals prove the power of good habits. Check labels before use. Never trust your memory to identify substances. Wipe down work surfaces, especially after handling sticky or oily liquids like this one. Report near-misses—spills, splashes, or the onset of skin irritation—so lessons spread before someone gets hurt. Stick to certified disposal services for waste. Take extra care until more is known about the long-term impacts of newer ionic liquids, including 1,3-dibutylimidazolium chloride. Awareness and responsibility, not overconfidence, keep workplaces safe and healthy for everyone.

A Close Look at a Unique Chemical Compound

1,3-Dibutylimidazolium chloride tends to show up in research labs focused on ionic liquids, catalysis, and even batteries. It’s a salt with some remarkable properties, used often for its stability and versatility. Still, safety and purity start at storage, no matter how impressive a chemical might be.

Temperature Matters

These types of ionic liquids usually do best away from extremes in heat or cold. A cool, dry place keeps the compound stable and prevents any breakdown or reaction with moisture in the air. Room temperature—ideally just below 25 degrees Celsius—keeps things steady. I’ve seen what happens when chemicals get left out in fluctuating heat: containers get crusty or wet, and sometimes labels even peel from condensation. Nobody wants to guess what’s actually inside each bottle. A steady climate cuts down on stress all around—not just for the chemical, but for the person working with it, too.

Keep It Dry for Purity

This salt pulls in water from the air. Humidity won’t just make a mess of the powder; it can start changing its chemistry. Tools like desiccators or even sealed containers with silica gel packs make a big difference. I remember watching a colleague lose an afternoon trying to reclaim material that had clumped and partially dissolved thanks to a humid summer. Clean, controlled storage took care of that problem for good the next season. Protecting chemicals from water always protects the next experiment, saving time and money in the long run.

Shield From Light and Air

Direct sunlight speeds up unwanted changes, even in something as robust as 1,3-dibutylimidazolium chloride. Opaque or amber-colored bottles block out the rays. Air exposure can slowly introduce contaminants, so keeping a tight lid on storage bottles makes a big difference. Every time you open a container, think about how much oxygen and dust could sneak in. Smaller aliquots for use stop the main supply from getting ruined after too many openings. I’ve seen this simple practice save plenty of lab budgets from buying new stock too soon.

Don’t Skip Labeling and Documentation

Even with a solid plan, chemical safety starts slipping without proper labels and records. Each container needs the chemical’s name, the date received, and any hazard pictograms required by regulations. Don’t trust memory alone—especially in a shared workspace. GHS-compliant labels help in case of accidents or inspections. I’ve seen well-meaning coworkers end up confused and waste valuable chemicals because someone left off the date or used shorthand nobody else understood. Digital inventories back up handwritten records so nothing gets lost during busy times.

Smart Organization Always Wins

Storing this compound away from acids, bases, and strong oxidizers prevents unwanted reactions. Keeping similar chemicals together by hazard class and separating incompatible ones can keep everybody safer. Shelves and cabinets designed for chemical use, with spill trays underneath, catch leaks or drips. Regular checks—monthly, if not more frequent—catch problems before they become emergencies. Creating a habit of safe storage limits risks and lets folks focus on the real work.

Responsible Storage Helps Everyone

Solid storage decisions don’t just protect a single bottle or experiment. They preserve budgets, scientific progress, and the safety of every person sharing that lab or storage room. Trying to cut corners on safe storage never pays off, and proper planning stands up to everyday challenges and the unexpected alike.

Looking at the Recipe

Getting from basic chemicals to a specialized ionic liquid such as 1,3-dibutylimidazolium chloride tells you a lot about both skill and safety in the lab. The process starts with imidazole, a simple aromatic heterocycle that chemistry students often meet early on. By adding butyl chloride under the right conditions and with careful timing, you can install butyl groups on both nitrogens at the 1 and 3 positions. The hydrochloric acid byproduct joins with the new cation to give the chloride salt—that's the target molecule.

A Closer Look at the Steps

I remember spending hours in the university lab, where working with alkyl halides like butyl chloride always meant good ventilation was a must. The reaction starts by dissolving imidazole in a dry solvent, such as acetonitrile, and adding butyl chloride dropwise with stirring. One butyl group attaches easily, but coaxing on the second takes a lot more patience and sometimes extra heat. Going slowly helps limit side-reactions that lower yields. A reflux setup keeps the solvent from boiling off and the mix concentrated, which makes the alkylation go to completion. Once the reaction stops producing gas (the smell of butyl chloride in the air shrinks), you cool everything down and move to purification.

Standard practice uses extraction and solvent washes to remove leftover reactants. Running the crude syrup through silica or washing with water helps separate the desired salt. I found that drying over magnesium sulfate or under a vacuum, then recrystallizing from ethanol, turns a sticky mess into solid 1,3-dibutylimidazolium chloride, which stores well and works reliably in later experiments.

Why Ionic Liquids Like This Matter

It’s tempting to see this as another odd organic compound, but ionic liquids such as 1,3-dibutylimidazolium chloride have opened new paths in green chemistry. Low vapor pressure means almost nothing evaporates—good news for air quality in labs. High thermal stability lets researchers push heat-driven reactions without fire hazards, a relief for anyone who's set off an alarm while heating traditional solvents. These materials often dissolve other ionic compounds that don't mix in water or organics, unlocking new catalytic processes and electrochemistry tools, including battery research and pharmaceutical synthesis.

Addressing Hazards and Real-World Use

Synthesizing such ionic liquids also raises safety and environmental concerns. Handling butyl chloride without a fume hood risks exposure to an irritant that can damage lungs and skin. In my own lab, gloves and goggles were non-negotiable, and spills drew instant attention. The quest for cleaner synthesis methods has pressed chemists to invent microwave-assisted reactions, solvent-free techniques, and recyclable catalysts. Peer-reviewed sources like the Journal of Organic Chemistry highlight routes that cut solvent use or allow milder reaction temperatures, protecting both workers and the planet.

Looking Toward Better Solutions

Many labs now look for starting materials from renewable sources and aim to recycle spent chemicals rather than dump them. Research teams partner with industry to scale up these processes while tracking waste and energy use. By sharing protocols openly and checking final products with tools like NMR and mass spectrometry (instead of relying on melting points and taste-tests of the past), chemists build a culture of quality and accountability. For students, learning hands-on with such materials teaches not just organic synthesis but a broader respect for safe, responsible science that supports progress in medicine, energy, and manufacturing.