1,3-Diethylimidazolium Acetate: Beyond the Basics

Historical Roots and Changing Needs

Chemistry starts small, with curiosity about how substances behave and transform. Lots of work in the late 20th century set the stage for new solvents. The discovery and use of ionic liquids, such as 1,3-diethylimidazolium acetate, followed a push to deal with volatile organic solvents and their impact on health and environment. Early on, chemists explored imidazolium salts hoping to sidestep tricky issues with older solvents. During the 1990s, when green chemistry became more than just an idea, this acetate-based compound offered something fresh. Its growth in research came hand-in-hand with a deeper understanding of ionic liquids’ properties and their modular design, both in academic and industrial labs.

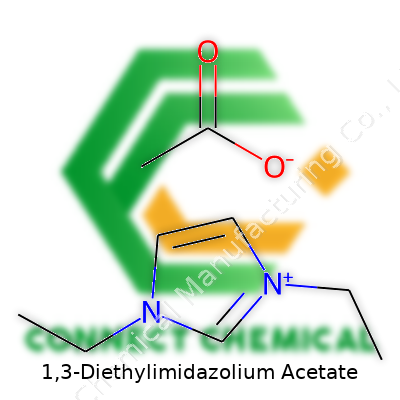

A Look at the Product

1,3-Diethylimidazolium acetate appears as a clear to pale yellow liquid. It usually arrives in tightly sealed bottles, meant for labs or specialty plant use. Its mild odor hints at the acetate presence. Bottles usually range from 10 grams to several kilograms, packed with warning labels detailing hazards, because this isn’t a chemical to take lightly. Trade names and synonyms crop up in catalogues: [C2mim][OAc], DEImAc, or Diethyl-Imidazolium Acetate, making life in the storeroom a little less straightforward. Most folks look for the CAS number (usually 661113-44-6) to be sure they’re pulling the right reagent from the shelf.

Physical and Chemical Properties

The ability of 1,3-diethylimidazolium acetate to stay liquid at room temperature—one highlight of this class—opens up options on the bench. It has a melting point well below zero Celsius, with the boiling point often too high to measure conveniently. Water loves to jump into the mix: this salt absorbs moisture from air if left open, which can spoil experiments. Its density floats a bit above water, and high ionic conductivity stands out compared to traditional molecular solvents. Lab tests show it dissolves cellulose, a big roadblock for ordinary solutions, and its miscibility with polar organics makes it popular for new extraction and synthesis work.

The Technical Details

Labels tend to shout technical specs. Purity—often 98% or higher—decides if a batch makes the research grade. Water content needs strict control, because wet ionic liquid throws off chemical calculations. Labeling should stick close to globally accepted standards: hazard pictograms, GHS codes, emergency numbers, and storage directions (“Keep tightly closed, protect from moisture, store away from oxidizers”). Strong, easily peeled labels matter; a missing identifier can spell disaster in a fast-paced lab. Certificates of analysis usually ride along with deliveries, giving the buyer luck with trusted batch data.

Preparation Method

Making 1,3-diethylimidazolium acetate looks simple on paper, but small missteps can mess with yield and purity. Most protocols start by alkylating imidazole with ethyl bromide in anhydrous conditions, building the diethylimidazolium backbone. After this, the halide is replaced using silver acetate, swapping out the unwanted ion and releasing the desired acetate salt. Excess starting materials and by-products like silver bromide have to be filtered away, then the salt purified—often through repeated washing and drying under vacuum, avoiding light and water. Experienced chemists tackle the process, checking for color and clarity, running NMR or IR to confirm the swap went smoothly.

Chemical Reactions and Tweaks

Modifications on the imidazolium ring allow designers to tweak the liquid’s properties—changing side chains, swapping out the counterion, or attaching functional groups. The acetate anion, strong and basic, helps break hydrogen bonds, making it a champion at dissolving stubborn organics like cellulose. On the flip side, chemical stability across a broad temperature range supports use in harsh reaction conditions. Some chemists have tried introducing extra unsaturations or branching on the ethyl chains, hoping for improved thermal resistance. These changes serve practical aims: better recyclability, greater selectivity, or compatibility with enzymatic processes.

Alternative Names and Identifiers

Confusion runs rampant in chemical trading because naming practices shift. “1,3-Diethylimidazolium acetate” stays safe, but “DEIM Acetate,” “Diethylimidazolium OAc,” and “[C2mim][Ac]” show up in global catalogs. CAS number 661113-44-6 keeps things tidy, often pasted alongside trade names. In house, researchers mark bottles DIEmimOAc or dEtImAc. Safety databases, shipping manifests, and customs forms care little for creative abbreviations—they want the full structure spelled out.

Safety in Handling and Daily Practice

No one wants a spill or exposure scare. Guidelines say to avoid breathing vapor, wear splash goggles and gloves rated for chemical resistance, and make sure air moves through well. The acetate anion can irritate eyes, skin, or lungs if not careful, and the imidazolium ring brings its own risks—rare, but worth respecting. Good labs keep a spill kit within reach, with protocols to treat accidental skin contact, inhalation, and fires (CO2 or dry powder works best; never water on electrical fires). Regular training and drills keep these habits sharp, because even seasoned professionals end up letting their guard down after long days.

Field Applications

Use cases for 1,3-diethylimidazolium acetate stretch from academic innovation to industrial practicality. The big draw? Cellulose and lignin dissolution, opening up new ways to process plant matter for biofuels, textiles, and plastics. Drug makers explore it in catalysis—where it boosts product yields at lower temperatures, sometimes acting as both solvent and catalyst. Its conductivity marks a place in batteries and other electrochemical cells, where safety and stability come at a premium. Environmental scientists use it to pull contaminants out of water, evaluating ways to minimize secondary pollution and maximize recovery. Upstream in the supply chain, mining operations treat stubborn ores using “green” protocols where possible, swinging back to cut the use of classic, hazardous organic solvents.

Research and Development Progress

Many university labs chase new modified ionic liquids, but 1,3-diethylimidazolium acetate keeps getting picked for projects on greener synthesis, sustainable processing, and recycling. Several groups engineer cellulose fibers for new materials with surprising mechanical properties—stretchy, strong, biodegradable. Teams in Asia and North America collaborate to optimize the recovery and reuse of the fluid after each process cycle. In catalysis, researchers measure how substrate scope, selectivity, and side reactions change compared to old-school solvents and newer ionic cousins. Others develop mixed solvent systems, combining acetate-based ionic liquids with deep eutectic solvents or renewable alcohols, reporting less energy-intensive workups. Each success gradually makes industrial roll-out less risky and more affordable.

Toxicity and Health Research

Every substance offers risk and reward, so figuring out toxicity matters. Lab and animal studies of imidazolium acetates show mixed outcomes: low acute toxicity for short exposures, but chronic effects and environmental buildup still under review. Skin and eye irritation turns up at higher exposures. In wastewater, the product lingers unless broken down by advanced oxidation or incineration, so process engineers build in traps and scrubbing stages. Workplace exposure limits remain under debate, but responsible companies push for the lowest achievable. Bioaccumulation doesn’t seem significant yet, but data gaps still exist. Ongoing research tracks breakdown products, seeking out subtle health effects through better analytic methods and standardized protocols.

Where Things Might Go from Here

Folks in green chemistry and process design want scalable, reliable, and less toxic options for everything from synthesizing drugs to recycling plastics into fuels. Right now, cost and handling skills hold back a full-scale switch to ionic liquids, but technical wins steadily stack up year by year. Young researchers dive into custom ionic liquid designs, crafting liquids for specific tasks. A race develops: who can balance safety, cost, recyclability, and raw material sourcing? Good progress drives investment, pulling in chemical suppliers and end users eager to claim a sustainable edge. Long-term, folks aim for closed-loop systems where every drop gets recovered—pushing for cradle-to-cradle chemistry in industry and beyond.

Changing the Game in Biomass Processing

Watching the rise of new materials always gets me thinking about the ways certain chemicals move beyond lab curiosity and start solving real problems. 1,3-Diethylimidazolium acetate, on the surface, looks like another liquid salt. Under the hood, it transforms how we break down plant material. The stubborn part of wood and straw, cellulose, usually laughs in the face of most solvents. Handling it used to involve harsh chemicals, big costs, and a lot of waste. This ionic liquid turns that process on its head.

Companies working on biofuel have struggled with breaking down cellulosic biomass without leaving toxic footprints. Enter this salt. Its deep ability to dissolve cellulose means you can reclaim sugars from straw, switchgrass, or even wood chips—opening doors for more sustainable fuel. The reason it matters: with the world aiming for cheaper, greener energy, every improvement in processing biomass makes the entire industry more viable. And there’s research from places like Oak Ridge National Laboratory showing real breakthroughs using this liquid, not just theoretical benefits.

Contributing to Green Chemistry

I’ve read plenty of industry journals, and the phrase “green chemistry” seems more popular than ever—though it often sits as a slogan more than a practice. This material pushes things further in a real sense. Its low toxicity makes it a strong candidate for greener alternatives to many traditional organic solvents. In pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals, this means a big reduction in hazardous waste streams. Less clean-up, safer working environments, and easier end-of-life disposal for these solvents.

You also get to reuse this ionic liquid over multiple cycles, slashing both costs and environmental impact. Labs and manufacturers relying on acetone or methylene chloride often look over their shoulders at compliance or waste issues. Shifting toward solvents like 1,3-Diethylimidazolium acetate sidesteps several classic headaches. There are papers from the American Chemical Society spelling this out—pointing to case studies where it replaces conventional solvents in dissolving and modifying various organic compounds.

Making a Mark in Material Science

Over the last decade, some colorful stories have come from researchers using these ionic liquids to design new polymers. Because it alters the way biopolymers behave, this acetate version helps scientists tweak materials for specific uses. For instance, turning plant waste into strong films that might one day replace certain plastics. There’s even emerging work using it to craft nanomaterials with unique electrical properties. My own experience in a pilot lab saw these liquids cut prep times and increase yields compared to the older, fossil-based solvents.

It’s not just talk in academic circles either. Startups and established players in the materials arena see this as a chance to jump ahead—especially as governments start pushing for bans on more toxic solvents. The versatility of 1,3-Diethylimidazolium acetate helps them stay nimble while still reaching high technical standards in the products they make.

Moving Forward

The more I follow trends in clean manufacturing and alternative energy, the more I recognize how small chemical advances trigger big changes. 1,3-Diethylimidazolium acetate may not grab headlines, but supporting greener fuels and safer lab practices puts it right in the story of the next decade’s innovation. Continued research, more industry partnerships, and open reporting on safety data are needed to push these benefits even further.

Understanding 1,3-Diethylimidazolium Acetate in Real-World Settings

People in the chemical field often talk about ionic liquids like 1,3-Diethylimidazolium Acetate. These modern solvents tempt researchers because they replace volatile organics and help tackle green chemistry’s challenges. Still, any substance able to dissolve tough biopolymers or bust up cellulose should raise questions about health, safety, and education—not just curiosity. Before grabbing a flask and pipette, anyone working with this material needs to pause and think through the risks.

What the Studies Show About Safety

While a freshly minted safety data sheet gives a first snapshot, decades of industrial work with quaternary ammonium and imidazolium salts teach us plenty. 1,3-Diethylimidazolium Acetate doesn’t have a splashy toxicity record in scientific reports. That offers some reassurance, yet the absence of horror stories is not a green light for goofing off. Most tested ionic liquids show low vapor pressure—meaning inhalation doesn’t top the risk list. The real exposure usually happens through skin or accidental splashes. Some early toxicology work highlights how these compounds may irritate skin, eyes, and mucous membranes. Over time, even “mild” irritation can slow a research team and drag down morale.

There is also evidence certain imidazolium salts persist in water and resist easy breakdown. That should make anyone think about environmental responsibility, especially if chemical drain disposal feels too casual. People in my old lab learned quickly that treating every new solvent with both healthy skepticism and respect prevented headaches and expensive cleanup later.

Practical Precautions That Work

No training day feels complete without a PPE demo. Goggles and nitrile gloves became non-negotiable for anyone pouring, pipetting, or mixing ionic liquids—no exceptions, even for the senior chemist in the corner office. Long sleeves and lab coats cut down accidental exposure when picking up bottles and cleaning spills. If you ever had a reaction splatter outside the hood, you’ll remember the sickly smell and wish you’d buttoned that coat all the way. It pays to fix those habits early.

For spills, the advice from industrial colleagues holds up: absorb any liquid with inert material, bag it, and dispose of it with hazardous waste—not down the sink. Closed containers and proper labeling matter just as much for acetate-based ionic liquids as they do for old-fashioned acids or bases. Nobody ever enjoys explaining a half-evaporated, unlabeled beaker to a safety inspector or a frustrated facility manager.

Building a Culture of Responsibility

In the rush of research, shortcuts appear tempting. I’ve seen trouble start when someone assumes a clear liquid “can’t be that bad.” Building habits from day one—simple training, clear signage, and strong peer reminders—makes prevention part of every routine. Regular group check-ins about material hazards beat solitary reading of safety sheets. People learn from hearing what went wrong and what worked.

Plenty of commercial labs support risk assessments and host workshops on new chemicals, far beyond what older generations received. That helps people understand how today’s risks might differ from yesterday’s, especially with emerging solvents like 1,3-Diethylimidazolium Acetate. Asking questions and double-checking safeguards doesn’t slow progress—it helps everyone get home at the end of the day with their health and their curiosity intact.

Why Purity Matters

Working with 1,3-Diethylimidazolium acetate, an ionic liquid gaining traction for its solvation power and low volatility, demands close attention to its purity. Too much water, trace solvents, or metal cations can pull experiments sideways—even a slight impurity may throw a wrench in cellulosic biomass processing or electrochemical applications. Researchers and lab techs keep an eye out for materials hitting the 97% to 99% purity mark. That’s where most reputable suppliers set their specifications. Lower grades create headaches in reactions where yield and reproducibility actually count. A tiny bit of sodium or chloride hitchhiking with your ionic liquid makes life miserable for anyone chasing clean analytical results.

Real-world purity checks rely on more than a supplier’s printout. Labs playing with these imidazolium salts usually run a batch through NMR or mass spectrometry. Extra peaks or strange signals mean something slipped in. Low water content also ranks high: Karl Fischer titration helps confirm the liquid hasn’t soaked in water vapor from humid air. Hydroscopicity here isn’t just a trivia fact—it’s the quickest route toward inconsistent performance and physical property drift.

Storage: Keeping Things Simple and Safe

Storing this ionic liquid doesn’t take a vault or a freezer, but a few solid habits make the biggest difference. Exposure to ambient air brings moisture right into the picture—the acetate anion forms hydrogen bonds with water faster than you’d expect. Flasks and bottles need tight seals, backed up by a desiccator if the air gets sticky. Leaving an open container out for an afternoon changes the composition. I’ve seen well-sealed samples from one week to the next look like syrup instead of clear liquid, proving the point about how quickly water finds its way in.

Room temperature is fine, as long as direct sunlight and heat sources stay out of the story. High heat doesn’t just risk evaporation or slow decomposition; it can also nudge the sample toward yellow or brown tints, usually a sign something inside started breaking down. A dry, dark drawer or chemical cabinet takes care of most of these problems. Don’t shove it in with reactive acids, oxidizers, or bases. Even a spill from a nearby bottle may start unpredictable chemistry before anyone realizes what happened.

Batch Quality: Trust but Verify

Trust in a batch comes from solid documentation and a quick look with your own equipment. I’ve learned labs sticking to monthly or quarterly re-checks—especially if their project budgets run tight—catch a lot of surprises before they snowball. Drying under light vacuum and maybe a gentle stream of inert gas, like nitrogen, finishes off what a factory desiccant pack can’t manage. Unlike classic organic solvents, ionic liquids like this one don’t start smelling off when they go bad, so there’s little margin for error with old or questionably stored stock.

Responsible Handling: Lab Culture and Safety

Colleagues new to handling ionic liquids often ask about leftover residues or handling. Gloves, goggles, and minimal open bench time work fine—no need for hazmat suits, but spills should get cleaned up fast to dodge slippery floors or skin contact. Labels, fresh storage vials, and a habit of re-checking water content form the backbone of responsible lab culture. Shortcuts in these steps lead to inconsistent runs and extra troubleshooting hours down the road.

It pays off remembering that careful storage and a watchful approach to purity don’t just make protocols easier—they save time, supplies, and reputation. For anyone dealing with the real-world messiness of research, investing a little care here keeps projects moving forward without ugly surprises.

Unlocking Cellulose with Modern Chemistry

Nature hands us cellulose in a tightly packed format, not eager to loosen its grip. Dissolving cellulose—whether for biofuels, new forms of packaging, or textiles—challenges even experienced chemists. Wood pulping uses a harsh set of chemicals, sometimes leaving behind an environmental mess. Biopolymers carry hopes of cleaner, greener futures, but their stubbornness complicates things. That’s why researchers keep their eyes peeled for less toxic, smarter solvents. Among those, ionic liquids have turned heads. One that’s drawn attention: 1,3-diethylimidazolium acetate.

Real World Results

From the bench to the beaker, 1,3-diethylimidazolium acetate doesn’t just sit pretty. It handles cellulose with more finesse than most older solvents. Lab teams in the US and Europe report this compound can dissolve cellulose at room temperature—no fireworks, just a clear solution from a mash of tough plant fibers.

Compared to standard ionic liquids, this one works thanks to its acetate group. Acetate actually breaks up the hydrogen bonds lashing the glucose units together. In the past, only a handful of compounds ever coaxed cellulose apart without damaging its backbone. So, chemists find themselves intrigued by something that finally does the job—without lye, without explosive risk, and with less environmental baggage.

Environmental Stakes and Industry

Solvents end up in waterways, soil, even the air—just ask anyone in a town downstream from an old paper mill. Toxic byproducts keep popping up in traditional cellulose processing. Ionic liquids seemed promising at first, but many early examples proved stubbornly toxic or impossible to recycle. 1,3-diethylimidazolium acetate is not risk-free, but it tends to hang together better and can be scrubbed and reused after a round of cellulose work.

I’ve seen research teams scale up from vials to buckets, watching as this liquid handles awkward plant matter. In some cases, the acetate version outperforms other ionic liquids when tested against more complex biopolymers: xylan, lignin, chitin. That points toward lower costs and maybe fewer side streams clogging up production.

Bumps Along the Way

One hard truth: ionic liquids do not offer a cure-all. Their price still outruns more established solvents, and the learning curve for waste management stays steep. Regulators ask hard questions about toxicity and eventual breakdown. Some ionic liquids linger in the ecosystem, so chemists and producers need to prove the acetate ion really lowers those risks.

Recycling matters the most—if you can recover the solvent, cycle after cycle, you start to see real gains in sustainability. A tight recycling loop shrinks both costs and footprint, but this only happens if technicians treat that recovery as a priority, not an afterthought. Teams who skip this step end up paying more, and risk more scrutiny as well.

Practical Steps Forward

Start with smaller production lines, build experience with recovery systems, and test both your solvent and residue for safety before thinking bigger. Connect lab chemists and environmental monitors early in the process. Your best chance for success comes from frequent, honest trial runs, digging into both effectiveness and aftereffects. Keep chasing less hazardous additives, and don’t fall for greenwashing. If 1,3-diethylimidazolium acetate can be recycled efficiently and breaks down harmlessly, the path looks brighter for industrial cellulose and other stubborn natural polymers.

The Real Story Behind This Ionic Liquid's Staying Power

Chemists working with ionic liquids often weigh the problems of stability and safe storage. Take 1,3-Diethylimidazolium Acetate. As someone who has spent time handling ionic liquids in a university lab, I’ve seen the impact that a tightly controlled environment can have on shelf life. These substances often come with a reputation for being tough and adaptable, yet small mistakes in storage ruin expensive batches and create safety hazards.

1,3-Diethylimidazolium Acetate usually shows strong chemical stability if handled with care. Its structure helps, since the imidazolium ring doesn’t easily break apart and acetate as an anion isn’t eager to get involved in random side reactions. A properly sealed amber glass bottle protects it from air and light, since oxygen and UV can, over time, prompt breakdown of imidazolium rings. If someone stores it in a dry, cool room, they can keep it for over a year with very little loss in purity. I recall opening a sample that had spent 18 months in a dark cupboard; analysis with NMR showed only minor changes—mostly small amounts of hydrolysis by-products.

Hazards of Moisture and Heat

The real challenge comes from water. Imidazolium-based liquids act like sponges, grabbing moisture from the air. After a while, too much water ruins experiments or makes measurements unreliable. Water can also start hydrolysis, which slowly eats away at the cation and the acetate, forming acetic acid and other compounds. Failing to take care with humidity eventually shows up as unexpected NMR peaks and sour smells—clear signs that the shelf life has dropped. Among trained researchers, daily practice means using a glove box or tightly sealing containers under dry nitrogen or argon.

Heat also spells trouble. Prolonged exposure above 40°C speeds up decomposition. Lab ovens and hot storage rooms have ruined more than one bottle in my research group. Decomposition products add unwanted color, lower ionic conductivity, and sometimes make the material downright hazardous. Reports in scientific literature back this up. A study in the journal “Green Chemistry” found decomposition kicks in above 60°C, producing volatile amines and acids. For both safety and quality, nobody should store these liquids near heat sources.

Supporting Stable Storage

Success starts with basic steps: amber glass bottles, dry storage cabinets, and careful labeling with acquisition and opening dates. Even at a large chemical supplier, routine checks of stock often catch bottles past their prime. Purity matters most for applications in catalysis, extraction, and even electrochemistry. Fresh samples run as smooth liquids with no color; degraded ones look cloudy or brown and smell acidic.

Possible Solutions Going Forward

Researchers have started blending in stabilizers to soak up moisture or adding small amounts of antioxidants. While that helps, best results still come from controlled storage. Suppliers who pack these liquids in airtight ampules—much like high-end pharmaceuticals—avoid many of the shelf life headaches.

Training plays a role too. Even graduate students just starting out can make a big difference by following handling protocols. Setting up workflows with glove boxes and regular checks of water content (using Karl Fischer titration, for example) saves a lot of money in the long run and keeps research running smoothly.

Most failures with 1,3-Diethylimidazolium Acetate arise from inattention, not the chemistry itself. In my view, this ionic liquid holds up well if treated as the valuable specialty chemical it is—give it the respect it deserves, and it won’t let you down.