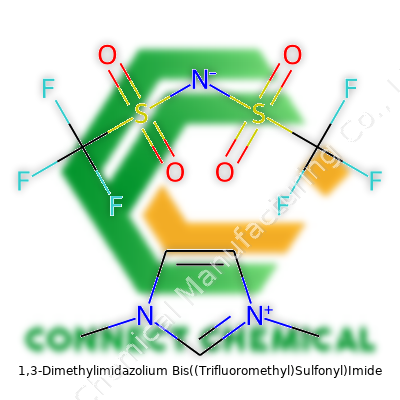

1,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide: An Essential Overview

Historical Development

By the late 1970s, researchers already looked for alternatives to flammable and toxic organic solvents. The discovery of ionic liquids — particularly those based on imidazolium cations and bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide anions — came at a time of real need for stable, non-volatile solvents in chemical manufacturing and analysis. As universities and major companies dug deeper, they saw that 1,3-dimethylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide, often abbreviated as [C1mim][NTf2], could weather high temperatures and carry out reactions where traditional solvents quickly failed. Its story is marked by stepping-stone discoveries: early research tried to tame the material’s corrosiveness and improve synthesis. Once the 1990s rolled in, the push for green chemistry highlighted ionic liquids. Environmental regulations ramped up, and the hunt for recyclable, less hazardous solvents gave a big boost to this compound. Now, it finds itself not just in niche labs, but across sectors handling cellulose, electronics, and electrochemistry.

Product Overview

1,3-Dimethylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide presents a colorless to pale yellow, viscous liquid at room temperature. Chemists know it for its negligible vapor pressure and strong resistance to thermal breakdown. Often stored in airtight bottles with Teflon-lined caps, this ionic liquid keeps moisture out, avoiding unwanted hydrolysis. Industry players tend to request it at high purity levels, often above 99%, because even a touch of water alters its performance. Its typical shelf life extends past a year if kept dry and shielded from sunlight. The most trusted suppliers back product batches with Certificates of Analysis, often featuring conductivity, water content, and residual halide levels—direct proof of the quality control that clients demand.

Physical & Chemical Properties

The melting point of [C1mim][NTf2] lands well below room temperature, leaving the liquid pourable even in cold climates. It features a density around 1.41 g/cm3, showing considerable heft compared to water or most organic solvents. The viscosity, which often measures several hundred centipoise, provides a slowly running flow but still supports stirring and mixing in laboratory reactors. This ionic liquid easily dissolves both polar and nonpolar molecules, behaving like a solvent and sometimes even a reagent in tough separations. Stability above 300°C opens the door to high-temperature syntheses. Chemically, the bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide anion gives robust resistance to oxidation and hydrolysis, making it popular in electroplating and battery research.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Purchasers find this compound labeled with its official name, formula (C7H11F6N3O4S2), and CAS number (367837-53-2). Specification sheets spell out purity, water content (Karl Fischer titration usually keeps it below 200 ppm), and impurity profiles from trace halides to free acid. The labeling process summarizes hazards, GHS symbols, recommended PPE, and safe storage instructions. Detailed traceability comes through batch numbers, which matter a lot for regulated industries like pharmaceuticals and electronics.

Preparation Method

Lab-scale synthesis commonly uses an alkylation route. Start with imidazole, methylate it twice with methyl halide under controlled, moisture-free conditions. The resulting 1,3-dimethylimidazolium halide reacts with lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide in aqueous solution. The desired ionic liquid phase separates out, often slick and heavier than water. Purification pulls off most unreacted salts and organic residues through sequential water washes, followed by drying under vacuum at 80°C or higher. Full-scale manufacturing avoids glassware, shifting to stainless steel reactors tightly sealed against air and water.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

In my experience working in materials labs, [C1mim][NTf2] takes pride of place as a nearly “inert” solvent for both polar and nonpolar reactions. Its tolerance against strong bases and acids allows for Michael additions, alkylations, and Diels–Alder cycloadditions that derail other solvents. Once I used it for catalytic C–C bond couplings at 150°C; it neither evaporated nor broke down. Chemists sometimes use it as a reaction medium for nucleophilic substitutions, Grignard additions, and Suzuki couplings with minimal side reactions. Derivatization targets the imidazoline ring — methyl substituents can be swapped or lengthened for tweaks in viscosity or solubility, supporting fine-tuning for specific industrial processes.

Synonyms & Product Names

It carries several monikers: 1,3-Dimethylimidazolium NTf2, [Dmim][NTf2], or simply [C1mim][NTf2]. Leading suppliers might call it by their proprietary names, tacking on qualifiers like “ultra-dry” or “high-purity” to signal added processing care. Product codes sometimes blend internal numbering and customer-facing shorthand for quick look-up.

Safety & Operational Standards

Toxicological studies remain inconclusive but smart researchers always treat ionic liquids with caution. Direct contact should be avoided to prevent skin and eye irritation. I always wore nitrile gloves and eye protection in the lab. Spills call for absorbent pads and ventilation rather than water flushing, since the liquid can form slippery films and resist breakdown in wastewater systems. Air and moisture-tight storage in plastic or non-corrosive metal containers keeps it from picking up trace water, which can affect both chemical stability and reaction outcomes. Local health and safety rules usually require fume hoods for any weighing, transfer, or disposal.

Application Area

The reach of [C1mim][NTf2] covers electrochemical devices, battery electrolytes, supercapacitor research, analytical extractions, cellulose dissolution, and catalysis. Its inert nature suits it for electroplating and as an engine for dissolution and regeneration of polymers like cellulose. In our university’s green chemistry project, students chose it to dissolve tough biomass for enzyme studies, sidestepping classic solvents that would denature proteins. Industrial electrochemists favor it for its room-temperature ionic conductivity and nonflammability, ticking boxes where old-school organic solvents raise too many red flags. The electronics industry explores this ionic liquid for specialty coatings and as a non-volatile solvent in microfabrication steps.

Research & Development

Ongoing projects in university and corporate labs look for new ways to tune [C1mim][NTf2] for greener, safer processes. Advanced groups measure ion transport in batteries and fuel cells, reporting on improvements to cycle life and ion mobility. Others tweak the structure using various alkyl groups, aiming for more biodegradable versions without losing the great thermal stability. Analytical scientists push boundaries by pairing it with chromatography, mass spectrometry, and microextraction, all while hunting for better reproducibility. Our faculty once combined it with deep eutectic solvents, resulting in a blend perfect for dissolving stubborn plant fibers for biofuel studies.

Toxicity Research

Recent toxicity studies show mixed signals — aquatic organisms face moderate chronic hazard if exposed long-term, but short-term, the risks seem lower than those tied to old-school solvents like dichloromethane. Still, no data shows it as risk-free for humans; extended, unprotected handling brings risk of dermatitis and mild respiratory irritation. Weighing these results, most labs limit exposure using closed systems, personal protective equipment, and training that treats ionic liquids as specialty chemicals — not benign materials. Environmental chemists follow breakdown pathways, learning that [C1mim][NTf2] holds up against microbial attack, leaving open the question of long-term accumulation in treated water.

Future Prospects

People working in both academic and industrial settings regularly anticipate broader adoption for [C1mim][NTf2] as process engineers hunt for less volatile, recyclable solvents. Pushes from both green chemistry advocates and strict regulatory requirements make this class of ionic liquids an attractive avenue for innovation. The challenge still lands on cost, especially for scaling up and meeting the purity levels demanded by medical or electronics-grade materials. Next-generation research looks to pair these ionic liquids with bio-derived components, or embed catalytic sites into their framework, opening doors for even more selective catalysis and energy storage. As greener production routes develop and recycling systems mature, prospects grow brighter for real-world implementation across everything from sustainable plastics to electric power technology.

Introduction to a Modern Chemical Player

Chemists watch the rise of new tools with curiosity. Among these, 1,3-dimethylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide—sometimes called [DMIM][TFSI]—has caught my attention more than once. This compound belongs to a class of ionic liquids that offer real advantages over traditional solvents. I’ve seen labs replace volatile, toxic organic solvents with ionic liquids, and the drive for cleaner chemistry keeps boosting that trend.

What Makes DMIM TFSI Special?

This stuff stands out for several reasons. It doesn’t evaporate easily, so you skip the headaches and odor from solvent loss. DMIM TFSI holds up under high temperatures and shrugs off moisture, which matters if you’re running reactions deep into the night or scaling up for industry.

Unlike the old solvents that show up on toxicity warning lists, DMIM TFSI keeps its cool in more ways than one. Fewer worries about fires, fewer harsh fumes, and less concern about tossing out barrels of hazardous waste. I remember scaling up a process, and every extra drum of toxic waste meant extra disposal fees and safety paperwork. These ionic liquids help dodge that bureaucracy.

Popular Uses in Modern Chemistry

High-tech batteries and capacitors take a lot from ionic liquids like DMIM TFSI. In the hunt for safer, longer-lasting energy storage, researchers found these salts stay stable as electrolytes. Lithium-ion battery makers want electrolytes that won’t catch fire and that push ions quickly between electrodes. DMIM TFSI doesn’t flinch, even as temperatures climb, so electric cars and grid storage companies look at it with real interest.

Synthetic chemists use DMIM TFSI as a reaction medium. Instead of swapping out for a new solvent with every step, this ionic liquid lets you build complicated molecules—often with better yields and less byproduct. Enzyme chemists appreciate the stability, too. Some proteins that fail in water can do a job in DMIM TFSI, staying active in processes that would otherwise kill them off.

Recycling scenes improved after ionic liquids turned up. I once visited a plant reclaiming precious metals from electronic waste. With DMIM TFSI, engineers separate out metals like gold or palladium without needing strong, caustic acids. The process becomes more selective and less toxic, letting workers breathe a little easier.

Environmental and Safety Considerations

No solvent gets a free pass. DMIM TFSI resists biodegradation, so it has to be collected and reused where possible. Labs keep it in closed loops or reclaim it before waste leaves the plant, minimizing leaks into water or soil. Some studies say ionic liquids break down slowly, so industrial users carry responsibility for watching effluent streams and documenting every step.

Toxicity varies by structure in ionic liquids. DMIM TFSI scores better than most, but anyone handling it keeps gloves and glasses close. Safety data keeps evolving, so manufacturers invest in more tests and greener synthesis routes, responding to those ECHA and EPA reports that often nudge industry forward before official laws change.

Moving Toward a Cleaner Chemistry Toolbox

Ionic liquids don’t wipe away the need for careful handling or clear architecture for waste. Many manufacturers now design processes around reuse and recycling, looking to future-proof their methods. To ride the wave toward greener chemistry, companies look for solvents like DMIM TFSI—balancing innovation, performance, and long-term responsibility. That’s my view from the lab and the plant floor.

The Reality of Chemical Handling

My background in laboratory work gave me a close-up look at what can go wrong during chemical handling. A slip of concentration can lead to skin irritation, rusted tools, or even a hospital visit. Government data suggests thousands of chemical accidents happen each year in workplaces. Many of these could have been avoided with basic safety habits.

Understanding the Hazards

Every chemical comes with its personality. Some cause a burning sensation if you get them on your skin. Others release invisible vapors that can knock you out or cause long-term lung damage. Bleach, for example, irritates the eyes and lungs with just a whiff. Strong acids can eat through clothing before you notice. It only takes a small spill to unleash trouble.

A material safety data sheet isn’t just paperwork—it's a roadmap. Inside are warnings about explosions, fires, or what happens if something splashes on your hands. I’ve seen young staff surprised by how a simple label holds information that keeps people out of harm’s way.

Common-Sense Protection Pays Off

Gloves aren’t an accessory, they’re a must. Not all gloves protect you from every chemical; nitrile works for solvents, thick rubber guards against acids. I never trusted thin latex for anything stronger than dish soap. Eye protection blocks splashes from chemicals that shoot out of bottles under pressure. Even a drop of something basic like ammonia stings the eyes far more than expected.

Mixing chemicals can be the quickest route to an emergency. Strong cleaners mixed with bleach release chlorine gas—a mistake that’s sent people to the ER. As tempting as it is to “just dump and rinse,” reading labels and double-checking compatibility saves lives.

Ventilation: Your Invisible Shield

Fumes drift faster than you think. I remember working in a closed storage room—nausea settled in before I even smelled the source. Opening windows, working under a vent, or moving tasks outside sidestepped headaches and nausea. Good airflow works as an invisible shield, dispersing vapors before they build up.

Never Skip Cleanup

Spills happen, but ignoring one sweeps danger under the rug for the next person who walks in. I kept absorbent pads and dedicated bins for used towels in arm’s reach. Simple habits like checking bottle caps and wiping up straight away prevented slippery floors and cross-contamination.

Training Makes a Difference

I’ve seen people freeze up during a chemical spill, unsure of what to grab. Regular drills—just running through an eyewash or locating the nearest exit—never felt like overkill after seeing someone use that knowledge for real. Teams that run practice drills spot mistakes before they hurt anyone.

Respect Goes a Long Way

Handling chemicals safely starts with a healthy dose of respect. Personal stories, news headlines, and official statistics all show one thing: it’s easier to avoid harm than to fix it. Gloves, eye gear, simple habits, and good communication turn a risky job into a manageable one.

Peeling Back the Layers of a Compound

Ask most people about the makeup of a common drug, cleaning agent, or even their favorite drink, and watch the conversation quiet down. Chemistry has a way of doing that—sometimes it feels locked behind jargon or long-winded classes, but the truth is, chemical structure opens a window into the real world. Learning how atoms line up, how bonds form, and why a simple tweak can turn a safe medicine into something toxic changes how we look at everyday stuff.

Getting Specific: Structure and Formula in Real Life

Every compound, whether it’s something as simple as table salt or as complex as insulin, has a signature. This signature, its chemical structure, shows where each atom fits into the puzzle. Sodium chloride, NaCl, stands as one of those compounds easy to write and easy to spot—a sodium atom, a chlorine atom, and a bond holding it all together. Now, shift over to something like glucose: C6H12O6. This one takes shape as a ring or chain, with specific links between carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen. How these atoms tie together explains why glucose fuels the body, while its relative, fructose, tastes sweeter even though it follows the same formula.

Real Consequences: Health, Innovation, and Safety

Looking at structure isn’t an academic game. In healthcare, the magic happens when a researcher tweaks a single atom or bond in a drug molecule, turning it from ineffective to life-saving, or reducing its side effects. Modern medicines for diabetes, cancer, and depression rely on a deep knowledge of chemical structure. One wrong guess means wasted years and lost trust. The same logic works in food safety, agriculture, or even environmental cleanup. Knowing that dioxins, for example, include a couple of chlorine atoms in certain positions, makes all the difference between a safe industrial byproduct and something that hangs around in soil for decades.

Getting the Information: Trust and Transparency

A reliable answer needs more than confidence. Chemists back up claims using tools that reveal structure: nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), infrared spectroscopy, and X-ray crystallography, among others. These aren’t magic wands—they demand patience, experience, and clear documentation. Open databases, peer-reviewed research, and published standards help anyone trace where the knowledge came from. Scrutiny and repeat tests matter, too. That’s especially true for anything going into our bodies or environment.

A Future with Fewer Unknowns

I’ve seen firsthand how confusion around chemical names and formulas blocks good decisions, whether it’s in a high school class or a professional kitchen dealing with cleaning chemicals. If people know what’s in a bottle, they make better choices. Policymakers, parents, and scientists all benefit when information isn’t buried in legalese or behind paywalls. Science, shared clearly, closes the gap between experts and the rest of us.

Bridging Gaps: Moving From Formula to Everyday Value

The periodic table and those strings of letters and numbers aren’t just there for tests—they shape everything from clean water to healthy bones. Recognizing a structure gives us control. It speeds up new discoveries, brings about safer products, and clears up confusion before it turns dangerous. It’s a skill worth picking up, no matter what field you’re in.

Why Storage Conditions Matter

Products never stay fresh by accident. In my past work with pharmaceutical ingredients, a single mistake in storage could wipe out a whole batch, which meant weeks of lost effort and real financial pain. Most people underestimate how light, air, and moisture wear down a product. Years ago, I learned this the hard way after my team left a sensitive chemical near a sunny window. It turned yellow overnight and lost its punch—not the sort of result anyone wants.

Spoilage doesn’t only hit chemicals. Coffee loses flavor sitting near the stove, and vitamins turn sticky when kept near the bathroom’s heat and humidity. No one wants to buy a sack of rice only to find it crawling with bugs after it sat out too long. A bit of planning in the storage space can protect your product for much longer.

Simple Storage Rules That Work

Start with the basics—control air, moisture, and light. In practice, this means choosing a clean, dry spot away from sunlight and big swings in temperature. Don’t tuck your goods away where pipes might drip or vents blow hot air; random conditions only speed up the breakdown process. At home, I store my extra yeast in the fridge, well-sealed, after a dozen failed bakes years ago showed how quickly air ruins freshness.

In industry, a sealed package in a temperature-controlled room keeps things steady. Typical guidance suggests a range of 15 to 25°C for most finished products. For highly reactive powders or pharmaceuticals, refrigeration around 2-8°C does wonders, but don’t freeze things unless the label gives the green light—freezing can change texture, clump powders, or even crack bottles. Humidity is another big enemy. Stick silica packs into containers once moisture starts creeping in. These grab excess moisture—and they’re cheap insurance, the reason so many products come with them embedded.

The Importance of Labeling and Monitoring

Modern packaging often comes with smart labels, temperature strips, or indicator dots. In my experience, these aren’t just corporate add-ons; they catch problems in time. A label fading from blue to pink can mean your cold chain broke and the whole lot may no longer work as promised. Always check labels for handling info. Manufacturers have spent hours figuring out what saves their products.

Some of the best companies train all their staff—not just managers—on proper storage. Even simple reminders work. I saw this at a customer’s warehouse, where big color-coded posters near shelves cut storage mistakes by half. It doesn’t require fancy tech; just a simple checklist does the trick.

Better Storage, Less Waste

Billions get lost every year to spoiled medicine, food, and raw materials. It hurts both wallets and the environment. The easiest fix is getting the basics right: use airtight, well-labeled containers, watch temperature swings, and keep things off the ground. For folks managing lots of products, software trackers with sensor alerts don’t just save money—they catch issues before they spiral.

Everyone wants products to last as long as possible. Stability isn’t luck. It’s the payoff for years of smart habits and attention to the smallest details—habits I trust more than even the fanciest machine.

Real-World Chemistry Behind the Question

Whether a compound dissolves in water or prefers an organic solvent isn’t an academic puzzle; it’s a decision that shapes how we design medicine, clean the kitchen, or even formulate shampoo. Day-to-day experience lines up with the science. If you’ve ever tried to mix oil and water, you’ve already run a solubility test. Most oils slide across the water’s surface without joining it. That observation came up again and again for me, in labs or at home. Mixing and matching new cleaning agents showed the same rule: “like dissolves like.” Water loves other polar substances,organics go with organics.

Why Molecules Choose Where to Dissolve

The heart of the matter comes down to chemical structure. Water stands out as a polar solvent, packed with molecules carrying positive and negative charges. Compounds with their own charged or polar parts—think table salt or sugar—break down easily in water. Sodium chloride, for instance, breaks into separate ions, which water welcomes thanks to its own charged ends. Organic solvents—a label covering liquids like ethanol, acetone, or hexane—carry less polarity or none at all. Hexane, made of carbon and hydrogen, doesn’t attract ions or polar molecules much, but it’s perfect for dissolving fats and waxes.

Testing this is just a matter of stirring. If you put benzoic acid in water and nothing floats or clumps after a good shake, it’s dissolving well. Try the same with naphthalene and nothing happens. Move to hexane, and naphthalene disappears without a trace. Each real-life experiment backs up the textbook theory. The reason behind it? Polar compounds dissolve in polar solvents; nonpolar compounds, with their limited charge distribution, need a nonpolar partner to mix well. It’s not magic; it’s pure chemical compatibility.

Why Solubility Clashes Matter Beyond the Lab

This science doesn’t stay in the lab. Pharmaceuticals only work if they dissolve where they need to, like in your stomach or bloodstream. Drugs engineered with water solubility in mind reach their target faster. If not, scientists build them to dissolve in organic solvents and coat them, so that the body can still absorb the active part. Agriculture faces the same challenge—herbicides break down in water for easy spraying, but if rain washes them away too quickly, they stop working or pollute streams. Every bottle of paint thinner or household cleaner has its label for a reason. A grease-stained shirt? Water alone won’t do it—you grab a detergent, which acts as a bridge, hugging both water and oil molecules, forcing them to mix and lifting stains away.

Facing the Roadblocks

Sometimes, you hit dead ends. Newly invented chemicals can be tricky: they might barely dissolve in either water or any of the common organic solvents. Food technologists, drug makers, and environmental teams all hit those walls. They rely on an old trick—changing temperature, mixing solvents, or tweaking the compound itself. Even then, surprises pop up. I’ve seen plenty of teams forced to reformulate products because the active ingredient didn’t play nicely with anything on their standard list.

So the question, “Is this compound soluble in water or organic solvents?” calls for both a careful look at chemistry and a dose of street smarts from everyday life. Solutions appear in every aisle of the store and every medicine cabinet. Our best results come from mixing textbook basics with what we learn from unpredictable real-world messes.