1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide: A Closer Look at a Modern Ionic Liquid

Historical Development

Ionic liquids came onto the scene as scientists wanted safer, less volatile alternatives to traditional organic solvents. The exploration of alkyl-substituted imidazolium compounds played a crucial part in expanding their practical use. By the early 2000s, researchers began focusing more on dialkylimidazolium derivatives, motivated by the desire to create solvents with tailored solubility properties and thermal stability. 1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide traces its story to these years, when labs worldwide scrambled for compounds that could handle high temperatures, offer wide electrochemical windows, and avoid the risk of flammability so common with many solvents. This move didn’t just rest on safety concerns; chemists also noticed that these ionic liquids could catalyze reactions, dissolve hard-to-handle biopolymers, and stabilize otherwise sensitive molecules. Over the years, demand for more efficient and versatile ionic liquids drove research and production, making this compound a mainstay for experimental work in academia and emerging green processing in various industries.

Product Overview

1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide shows up as a pale yellow to colorless oily liquid, sometimes appearing slightly viscous depending on air temperature. Labs store this salt for its ability to dissolve both polar and non-polar compounds, and it rarely emits much odor. Chemists count on it for fine-tuning solubility in extraction processes, aiding in electrolyte solutions, and acting as a transition metal catalyst stabilizer. Its hydrophobicity, stemming from the octyl chains, opens up separation tasks between water and organic mixtures—something I’ve encountered firsthand working with extraction protocols for rare earth elements where water-soluble options just wouldn’t cut it.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Most users report a melting point well below room temperature—meaning unless you freeze the lab, this material will not solidify. The molecular weight lands near 444 g/mol, so one quickly notes the density compared to typical organic liquids. This ionic liquid resists decomposition until well above 200°C, and resists evaporation, with a practically negligible vapor pressure. Polarity stays moderate, but the long alkyl chains impart significant hydrophobicity. This allows 1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide to remain immiscible with water, but latch onto organic phases, making it invaluable during selective extraction routines. Electric conductivity remains modest, as the viscosity limits ionic mobility, but with a bit of temperature adjustment, one can dial this up for electrochemical work. Stability against most oxidizers and common acids makes it a reliable workhorse, although storing away from strong bases and reducing agents proves prudent.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Standard laboratory labels for 1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide note a purity of at least 98%, often accompanied by a batch number and a moisture content below 0.5%—crucial for reproducible experimental results. Companies sometimes offer both reagent and technical grades, but for analytical work, the higher-purity batch always makes a difference. The label carries hazard pictograms warning of eye and skin irritation, and packaging usually holds the substance in glass or high-density polyethylene bottles to prevent corrosion or leaching. Storage suggestions outline avoiding sunlight and keeping the bottle tightly sealed at room temperature. In a research setting, double-checking lot-specific details feels more like a necessity than a formality given how subtle impurities can shift solution behavior.

Preparation Method

Production most often starts with 1,3-dioctylimidazole, itself made by alkylating imidazole with 1-bromooctane. The resulting imidazole undergoes quaternization, usually by dissolving it in acetonitrile or toluene and adding excess bromooctane. Heating encourages completion, then the reaction mixture cools down, causing 1,3-dioctylimidazolium bromide to separate. Chemists rinse the crude product several times with water to scrub out unreacted material and keep ionic strength in check. Recrystallization from ethanol or evaporation of the solvent further purifies the salt. From my own bench experience, paying attention to each wash greatly affects purity—any leftover alkyl bromide brings up the risk of unwanted byproducts in later use, which can derail delicate extractions or catalytic cycles.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The imidazolium cation in this molecule provides a platform for further functionalization. Swapping out the bromide for other anions like PF6-, BF4-, or NTf2- gives access to a new set of physical behaviors: increased hydrophobicity, greater electrochemical stability, or unique solvation properties. The long octyl side chains invite further modification by oxidation, sulfonation, or even cross-metathesis, producing tailored ionic liquids for targeted applications. Reaction with silver nitrate swaps bromide for nitrate, while alkylating the nitrogen ring or introducing functional groups at the 2-position allows chemists to tinker with viscosity and phase separation. Such flexibility has often meant short experiments in the lab expand into months of tweaking—no two syntheses ever yield quite the same texture or response, especially when partial chain oxidation creeps in during workup.

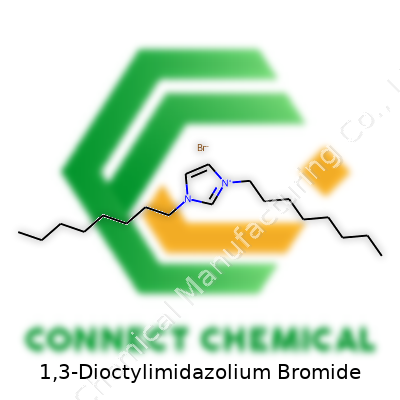

Synonyms & Product Names

One may spot this compound under various names: 1,3-Dioctyl-1H-imidazol-3-ium bromide, DoiB, or by its product code in vendor catalogs. Labels emphasize the imidazolium core structure and the C8 side chains, while the bromide anion sometimes appears as simply “Br-.” Several chemical suppliers sell it under tradenames that reflect their own purity grades or intended uses—distinctions worth noting before attempting high-sensitivity measurements or electrochemical studies.

Safety & Operational Standards

Despite its low volatility, 1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide irritates eyes and skin on contact, so gloves and goggles must stay on throughout handling. Splash risk can feel low because of its oily nature, but it’s adhesive and can make cleanup annoying if spilled. Fume hoods, spill trays, and ready access to soap and water make a difference. Disposal follows the standard for non-volatile organics, routed through chemical waste streams instead of regular sinks. Fire hazards rarely pop up, but the compound should not mix with strong oxidizing agents or bases. Documenting lot numbers and keeping detailed chain-of-custody logs lets teams track performance and recall information if impurities or inconsistent behavior surface. From working in shared labs, having clear storage and labeling rules means fewer misunderstandings or cross-contamination—key for reproducibility and research integrity.

Application Area

1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide has charted an impressive resume across industries. Chemists lean on it as a solvent and phase-transfer agent, exploiting its hydrophobic nature for liquid-liquid extraction of metal ions, dyes, and pharmaceuticals. Its thermal and chemical stability earn it a spot in batteries and electrochemical cells, often as part of non-aqueous electrolytes that need to operate at high temperature. Materials scientists use it as a template and stabilizer in synthesizing nanoparticles—especially gold and silver—thanks to its tendency to prevent aggregation. In organic synthesis, this ionic liquid accelerates some reactions and finds a niche as an environmentally benign replacement for harsh solvents. Researchers working on biomass dissolution and processing, myself included, see real value in its ability to disrupt stubborn polymer matrices, speeding up the breakdown and analysis of lignocellulose. Even in analytical chemistry, the compound shows up in sample preparation for chromatography and trace element extraction, giving new options where conventional solvents fall short.

Research & Development

In the past decade, funded projects and academic labs steadily widened the properties of imidazolium ionic liquids. Much of the focus lands on eco-friendliness, designing derivatives that break down more easily or lose less into the environment. Studies show that by changing side chain length or swapping out the anion, one can dramatically influence performance—creating customized solvents for each task. Ongoing collaborations between universities and industry partners push for ionic liquids that tick every box: renewable sourcing, high thermal stability, and minimal toxicity. Grant proposals echo these goals, seeking alternative pathways for large-scale synthesis that cut cost and limit waste streams. My recent review of published patents highlights just how creative teams have become in blending 1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide with other ionic or molecular components, yielding hybrid systems that outperform either parent in extraction rates, selectivity, or recyclability.

Toxicity Research

While early on some reports downplayed environmental risks for 1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide, more detailed studies paint a complex picture. Acute toxicity in aquatic systems remains low in comparison to traditional organic solvents, but chronic exposure hints at bioaccumulation concerns—especially as the compound degrades slowly in natural environments. Its long alkyl chains resist microbial breakdown, leading researchers to test biodegradable analogs or engineered strains that might handle wastewater better. For lab personnel, symptoms from accidental skin exposure stick mostly to irritation, but ingestion carries more serious health risks. Keeping up with safety data sheets and monitoring for new research updates feels like a necessary habit, especially as regulations tighten across the EU and North America. Regular training for safe handling and waste procedures, anchored on current toxicological reports, helps reduce health hazards and limit lab-based environmental discharge.

Future Prospects

Momentum keeps building for applications that demand sustainable, versatile, and high-performance fluids—traits 1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide clearly meets. Future prospects look especially strong for advanced battery systems, green chemistry catalysis, and circular economy technologies that turn waste into value-added products. The field continues to explore chain branching and functional substitution to address environmental persistence. Pilot projects already test this compound’s suitability in medical extraction, renewable plastics, and even CO2 capture from air or exhaust streams. The balance between functional benefits and responsible use will determine adoption rates—clear protocols and regular review of literature findings can help firms navigate this fast-changing regulatory climate. For anyone in the trenches of chemical innovation, keeping an eye on emerging analogs and smarter disposal methods seems the wisest path forward.

What Happens in the Lab Doesn’t Always Stay There

Every so often, a compound comes along that promises more than just chemical stability. 1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide often ends up on the benches of folks working with ionic liquids, but its reach is much broader. I’ve seen researchers get excited about it not because it sounds futuristic, but because it works. Practical applications drive the chemistry—not just textbook theory.

Green Chemistry in Action

Chemists want cleaner, more efficient processes, and the industry sees ionic liquids as a friend. This compound, built around the imidazolium core but stretched with long octyl chains, keeps things running smoothly as a solvent for organic synthesis and catalysis. Its structure lets it dissolve both polar and non-polar materials, cutting out the need for some traditional, harsher solvents. This edge has played out in biofuel research, especially in breaking down plant material like cellulose, turning what’s tough into what’s useful without so much waste. I remember reading studies where yields climb and waste drops, just by switching to this salt.

Electrochemistry and Energy: Not Just Buzzwords

Labs working with batteries and fuel cells keep an eye on conductivity and electrochemical stability. The bulky alkyl groups on this salt lower its melting point, turning it into a liquid with better ionic movement at room temperature. That means safer, sustainable electrolyte options over volatile organic counterparts. Some folks have shown improved energy storage using ionic liquids like this one, charging and discharging batteries with a bit more punch and less risk of fire.

Material Science Gets a Nudge Forward

Mixing this compound into polymers or nanoparticles changes a material’s properties—sometimes making it more flexible, sometimes simply more stable in humid or hot environments. I’ve watched researchers use it to tweak carbon nanotubes, getting them just right for sensors or membranes. Environmental engineers have also explored using these custom materials for cleaning up oil spills or recovering heavy metals from water, all thanks to the ionic liquid’s unique interactions.

Cleaning Up Catalysis

Transition metal catalysts find a friend here. The bromide and imidazolium structure stabilizes metal centers, helping reactions run faster or at lower temperatures. This means lower energy bills and less stress on equipment. Some big pharmaceutical projects have switched to ionic liquid supports to get cleaner products without the drag of byproducts from other liquid systems.

Room for Better Ideas

There’s excitement about the number of puzzles left to solve. Disposal, recycling, and price still create debate. Some researchers suggest using plant-based feedstocks to make production greener. Others push for circular approaches—reclaiming and recycling the salt after use, so it lasts for more than one round of reactions.

The Real Takeaway

Practical value comes down to results. If an ionic liquid helps researchers make better batteries, efficient biofuels, or cleaner pharmaceuticals, that changes more than just a lab report—it shifts what ends up in our homes and cities. When results matter, compounds like 1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide show why chemistry stays at the center of progress.

Looking at the Building Blocks

One glance at 1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide, and its name already hints at long carbon chains attached to an imidazole ring. In plain terms, this molecule has an imidazolium core—a five-membered ring with two nitrogens—decorated with octyl groups on the first and third nitrogen atoms. These octyl chains stretch out, each nine carbons long if you count the nitrogen connection, which contributes to the molecule’s bulky character.

The chemical formula stands as C19H37N2Br. The imidazolium ring—found in many ionic liquids and solvents—serves as the backbone. Attach those octyl chains, and you get a structure that looks like this: two separate, long hydrocarbon tails branching off of the same ring. Add the bromide anion, and the molecule takes shape.

Molecular Weight and Practical Numbers

With all atoms accounted for, the molecular weight is a solid 389.42 g/mol. This becomes more than trivia the moment you have to measure out quantities in a lab or scale up for production.

From my time working with ionic compounds, every gram—every decimal point—can influence reaction yields, purity, and even regulatory paperwork. A miscalculation on molecular weight burns time, money, and patience fast, especially when tight margins rule chemical production.

Relevance Beyond Structure

Imidazolium compounds crop up across research, from green chemistry to electrochemistry. What makes the dioctyl derivative worth a closer look? Those long alkyl chains boost hydrophobicity and lower the melting point, meaning that as ionic liquids go, this one stays fluid over a broad range. That opens up options for solvents that don’t dry out or degrade under heat, making processes more robust.

A feature of ionic liquids like this: traditional organic solvents evaporate and pollute; ones with imidazolium cations stick around, offering a safer alternative for everyone from bench scientists to folks working on battery tech or pharmaceuticals. Ionic liquids have grown as more people push to cut hazardous waste and seek greener choices. Statistics from academic journals report that over the last decade, ionic liquids have shown up in thousands of renewable energy papers, especially where high stability and low volatility matter.

Challenges and Improvements

Of course, nothing in chemistry comes gift-wrapped and trouble-free. Synthesis for 1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide asks for careful purification; side reactions and impurities easily muddle the product. On top of that, the sourcing for long carbon chains raises questions about renewable feedstocks and the energy footprint of synthesis. Some researchers have started to explore bio-based octyl chains—sustainability has begun to matter as much as performance.

Waste management for old or degraded ionic liquids calls for more attention too. While these chemicals don’t evaporate easily, their breakdown products or accidental spills can persist in the environment. Pushing for better, closed-loop recycling or enzymatic breakdown methods could shrink the environmental costs.

Staying Grounded in Practicality

I’ve learned that chasing new molecules means handling the real-life ripples each chemical creates—safety, cost, supply chain, environmental impact. The structure and molecular weight are never just numbers; they shape what happens in the lab, in manufacturing, and even in regulations. Finding practical, sustainable ways to use electrolytes like 1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide will keep everyone honest about what chemistry can—and should—achieve.

A Chemical Not to Take Lightly

Anyone who’s spent time in research knows that new compounds often come with their own quirks. 1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide falls squarely in that category. With more labs leaning into ionic liquids for green chemistry and solvent research, this salt has started turning up everywhere from grad student benches to cutting-edge industry setups. The same properties that make it interesting in the lab — decent stability, unique structure — ask for a careful hand outside of experimental runs.

Storing it Right

Coming back to the basics, dryness matters. Letting moisture sneak in isn’t just a hassle, it leads to impurities, ruined batches, and headaches for anyone chasing clean data. Airtight glass bottles work best. In some of my own projects, we labeled them with actual dates every single time that bottle opened, just to track even short-term exposure. Tossing a desiccant pack inside the storage cabinet gives a good extra layer of protection.

Keep it out of sunlight and clear of the bench’s edge. Heat speeds up decomposition and unpredictable reactions — nothing novel there, but way too many accidents happen from just ignoring that simple rule. Ideally, shelve all containers in a dedicated dry box or pull-out drawer, marked with both chemical name and a hazard warning.

Personal Gear: It’s Worth the Hassle

You’ll find people get lazy about gloves. That’s a mistake. This compound lacks an extensive health profile, but the imidazolium family of compounds sometimes shows skin sensitivity and mild toxicity. You don’t want to test that by accident. Single-use nitrile gloves plus an old-fashioned lab coat shield against any quick spill, even if it seems unlikely.

Careful hands avoid trouble: pour small amounts over a tray, never refilling large containers in the open, and wipe up any grains that escape onto scales or benches. If a splash lands on skin, cleaning the spot with soap and lots of water works best — no fancy washes needed. For eyes, reach for that emergency eyewash without pause.

Ventilation Makes a Difference

One trick I picked up: even seemingly stable salts produce dust, especially when they’re packed for the first time after shipping. Throwing a bottle open in a cramped, poorly ventilated room makes a local mess you’ll smell for hours. Fume hoods aren’t just for show — work upwind and keep that air moving, especially for transfers or weighing larger quantities.

Emergency Plans Aren’t Optional

Chemical safety routines sound repetitive, but ignoring them just isn’t worth the regret. Make sure spill kits are ready, not hidden behind a heap of unrelated containers. Store a printed safety data sheet nearby, not on a shared computer buried in e-mails. I’ve run drills where only muscle memory mattered — what you do in those first five seconds leaves the biggest mark.

Disposal: Not Down the Drain

After handling, careful waste collection wraps up safe lab work. Saving labeled bags or jars for leftover vials or gloves prevents confusion. Our university policy called for solid and liquid wastes to go in separate bins, with solvents logged in a notebook for hazardous waste pickup. No shortcuts or drain dumps; the chain of responsibility doesn’t end until that waste pickup leaves the building.

Final Thought: Details Make Safety Real

From what I’ve seen, safety culture isn’t about locking everything behind complicated protocols. It’s about habits — double-checking lids, scanning for leaks, grabbing gloves before the bottle, and thinking ahead about what could go wrong. 1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide, like so many specialty salts, shows respect to those who respect the details.

Understanding What Makes 1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide Special

Chemicals like 1,3-dioctylimidazolium bromide, a member of the ionic liquid family, challenge the way we think about solvents and mixing. This compound steps away from the rules of classic organic molecules because ionic liquids—salts in a liquid state—play by their own rules. People working in labs notice right away: this material doesn’t behave like sodium chloride or sugar in water. Its bulky alkyl chains shoot out from the imidazolium core, making it different from your typical salt.

Water and Oil: Solubility Face-off

If you take a container of water and toss in a pinch of 1,3-dioctylimidazolium bromide, the compound tends to go its own way. Long octyl chains on both sides of the molecule resist mixing with water, almost like how oil stubbornly sits on top of your salad dressing. Water loves working with polar or charged substances, yet those hefty hydrocarbon tails act more like a waterproof jacket. Observations in the lab back this up—this chemical offers poor water solubility.

Shifting over to organic solvents brings out a different side of the story. Organic solvents such as chloroform, dichloromethane, and toluene contain molecules that are also organized around carbon and hydrogen. The hydrophobic sections of 1,3-dioctylimidazolium bromide dissolve more easily into these environments. Researchers have found that ionic liquids with extended hydrocarbon tails blend more readily into these organic environments than regular ionic salts. This trend repeats itself with others in the same chemical family.

Why Chemists Care About Solubility

Solubility might sound like a technical detail, but it shapes real-world problems and breakthroughs. In the lab, this quality decides how a compound gets used. Take an extraction process, for example: if you want to separate out a material from a water-based solution, an ionic liquid that prefers organic solvents can help pull out valuable chemicals. Pharmaceutical companies and materials scientists lean on these features to create purer products or to control reactions that run faster or cleaner.

Problems arise if students or scientists expect ionic liquids to blend easily with any liquid. This assumption can waste both time and costly materials. To save effort, chemists turn to reference works and hands-on tests. The Handbook of Ionic Liquids and databases like PubChem have summarized experimental data showing that 1,3-dioctylimidazolium bromide dissolves far better in organic solvents than in water. Simple “shake flask” tests or more advanced solubility analyses confirm these findings repeatedly.

Making Better Choices in the Lab

Mixing chemicals with an eye to solubility cuts down on waste and opens new technological doors. For anyone planning a synthesis or separation, knowing that 1,3-dioctylimidazolium bromide avoids water and prefers organic solvents helps direct the experiment. This knowledge supports safer working conditions, prevents spills and helps with more accurate measurements. It can even make recycling ionic liquids cheaper and more straightforward, reducing environmental impact.

Clear data on solubility supports researchers in designing better processes, whether they’re scaling up a reaction or just getting repeatable results. Understanding how 1,3-dioctylimidazolium bromide fits into the bigger picture of ionic liquids also encourages smarter choices in both academic and industrial labs.

What Is 1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide?

1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide falls into the category of ionic liquids—those salty, room-temperature liquids that have gained popularity in advanced chemistry, clean energy research, and certain industrial processes. Its unique properties allow it to dissolve tough compounds and interact with a range of chemicals, which sounds promising for green chemistry. Trouble comes when you unpack what this compound means for health and the environment.

Possible Health Risks

Direct exposure to 1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide can raise some real concerns. Studies in peer-reviewed journals suggest ionic liquids share structural features with known toxic compounds. What scientists have observed: these substances can cause cell membrane damage, disrupt hormone functions, and sometimes stick around in organs. Skin contact with improperly handled substances like this increases the risk of irritation or even chemical burns for those unprotected. Extended inhalation of dust or vapor—an uncommon but possible risk in labs not following protocols—has a history of leading to respiratory irritation.

Nobody wants to be the person in the lab who learns about long-term effects the hard way. Earlier in my studies, our group handled a similar compound, and several team members had skin reactions until we switched to longer gloves and improved fume extraction. Safety training is not just paperwork; it acts as your insurance against unforeseen accidents. Users trust that basic precautions, like personal protective equipment and good ventilation, are non-negotiable.

Environmental Hazards

On the environmental side, ionic liquids look better than traditional solvents because they don’t evaporate as fast. Still, that low vapor pressure means they stick around if spilled or dumped. High persistence brings bioaccumulation risks for aquatic life if this chemical escapes into waterways. Studies have shown that even low concentrations can harm algae and fish eggs, throwing off the local food web. Researchers found that 1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide can impair cell division in plant roots, which rings alarm bells for anyone working near soil or plant research facilities.

Disposal presents another challenge. Facilities sometimes lack guidelines that address the quirks of ionic liquids, so someone might pour leftovers down the drain, thinking water treatment will handle it. Conventional treatment plants are rarely equipped for these types of chemicals, and even advanced oxidation can fall short, meaning trace amounts slip through.

Moving Toward Safer Use and Disposal

Solutions start with education. Lab managers and industrial staff need real-world hazard training identifying and mitigating risks associated with these newer compounds, not just the ones from textbooks. Industry can encourage safer alternatives or modifications to the chemical structure that reduce toxicity without dropping performance. For smaller operations, keeping a logbook of chemical use and disposal methods provides accountability and a reason to rethink before dumping anything down the drain.

Better labeling also goes a long way. Too often, specialty chemicals arrive without clear risk information written in plain language. Regulators and suppliers who prioritize detailed, understandable labeling help create a safety-first culture. Collaboration between regulators, scientists, and workers on these best practices matters as much as the technology itself. Only thoughtful, proactive steps ensure chemicals like 1,3-Dioctylimidazolium Bromide stay tools, not threats, in our pursuit of innovation.