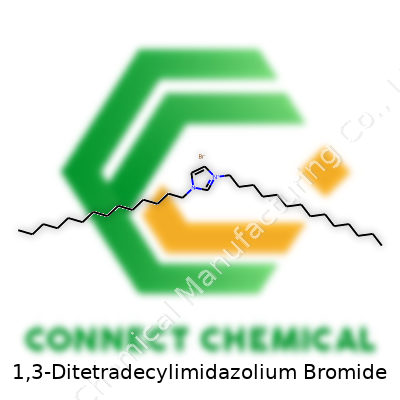

Exploring 1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium Bromide: Insights and Impact

Historical Development

People curious about ionic liquids often stumble on names few outside of specialty chemistry circles would recognize. 1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium Bromide isn't something you'd find in an everyday pantry, but those tracking its history will note a steady rise alongside the broader search for advanced solvents and functional materials. The journey began within the wave of work on imidazolium-based salts—pioneered in the late 20th century as an answer to growing interest in “green chemistry.” Early publications pointed out these compounds managed to take on tasks typically dominated by traditional volatile organic solvents, while sidestepping their environmental baggage. Over the last few decades, researchers built new variants as they chased better stability, improved ionic conductance, and specific molecular “tweaks” that unlocked unexpected uses, each new generation more finely tuned than the last.

Product Overview

1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium Bromide stands apart from its simpler cousins thanks to those long tetradecyl tails. In laboratories, its standout feature includes both hydrophobic character and robust ionic conductivity. These attributes drew attention from engineers, not just pure chemists. Aside from its basic function, practical applications gave this compound a role in oil recovery, designing next-generation batteries, and improving materials in nanotechnology. Companies producing it rarely stick to small-batch runs—this compound has found demand in bulk for research, pilot plants, and niche manufacturing projects eager for alternatives to more hazardous or less effective chemicals.

Physical and Chemical Properties

Run a hand through sample data sheets or glance at a beaker in the lab, and you’ll spot a pale, waxy solid melting at temperatures usually closer to cooking oil than salt. Its structure, comprising a bulky imidazolium core and two extended hydrocarbon arms, limits volatility and boosts chemical stubbornness—meaning it resists breakdown, even when pushed with heat or exposed to strongly basic or acidic surroundings. Water doesn't mix easily with it, which can make cleanup trickier but also helps in extraction or liquid–liquid separation processes. Chemically, its ionic nature aids dissolution in select organic solvents, and the bromide counterion’s presence steers solubility and reactivity in a range of scenarios.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Suppliers tend to list purity levels topping 98%, and color or moisture content marks a quick check for contamination or improper storage. Each batch receives a unique lot number, required labeling on all containers, and up-to-date safety documentation—hazard pictograms from global harmonized standards now appear on bottles, a detail that matters both for lab workers and shipping companies. One aspect that gets overlooked sometimes: batch-to-batch consistency plays a massive role for researchers relying on this compound in high-precision experiments. Even a one-percent shift in impurity levels might skew battery chemistry tests or nanomaterial synthesis, so quality controls remain strict by necessity.

Preparation Method

Synthesis hinges on alkylation chemistry—starting from imidazole, reacting with tetradecyl bromide under controlled temperatures, all in an anhydrous environment. Personal experience tells me, working with long alkyl-chain bromides means creating a sticky, often stubborn intermediate that demands patience. The bromination step introduces hazards, including toxic fumes and byproduct control, so anyone scaling up has to invest in solid fume hoods and careful waste management. Purification turns out to be more challenging than for smaller imidazolium ions, as the big hydrophobic chains resist dissolution in the typical polar solvent washes, demanding more ingenuity from whoever’s running the flask.

Chemical Reactions and Modifications

Out beyond the basic salt, chemists discovered that swapping the bromide for other anions (hexafluorophosphate or tetrafluoroborate, for example) fine-tunes properties for niche needs—each new pairing changing solubility, reactivity, or thermal stability. On the cationic side, those long alkyl chains can’t swap easily, but functionalizing the imidazolium ring or tiny tweaks to chain length adjusts viscosity or lubricating ability. These routes have flourished as researchers seek additives or functional liquids that work under stress, high temperature, or exposure to metals.

Synonyms and Product Names

This compound floats around under several brandings and registry names, depending on whose catalog or scientific paper you consult. Names like “1,3-bis(tetradecyl)imidazolium bromide” or “C14imBr” crop up, sometimes with slightly shuffled numbering or descriptors. Commercial suppliers stamp private codes or catalog numbers on their bottles, and anyone ordering needs to double-check structure and specs—relying only on a shorthand name sometimes leads to frustrating errors in purchasing or handling, since a missing or misplaced decyl group can mean a different surfactant, not just a minor shift in performance.

Safety and Operational Standards

From hands-on experience, safety demands both technical knowledge and basic caution. 1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium Bromide itself stands less hazardous than many legacy solvents—volatility and acute toxicity run lower than chloroform or toluene—but skin and eye protection remains critical, since contact risks irritation, and chronic exposure outcomes haven’t been fully charted. Labs rely on gloves, goggles, and judicious use of gloves and extraction systems, especially during synthesis. Waste needs full documentation and proper treatment, considering the compound’s slow biodegradation and potential impact on aquatic systems if it escapes containment. Regulatory bodies have yet to draft specific standards nationally or globally for every member of this family, so users often borrow best practices from parallel chemicals.

Application Areas

In my work with advanced materials groups, this ionic liquid often surfaces as a component in complex formulations: as a solvent or electrolyte in batteries, as a template in nanoparticle engineering, or as a phase transfer agent in stubborn organic transformations. There’s buzz within green processing circles for its role in cutting out volatile organic solvents from protocols, even in well-worn applications like polymer processing or catalysis. A recent case saw it saving precious catalyst by holding metal ions in solution through multiple cycles, slashing overall costs and waste. Despite these promising uses, no one calls it a cure-all, as cost-of-production and sometimes disposal issues push engineers to weigh trade-offs carefully.

Research and Development

Interest in next-generation ionic liquids remains strong, and research groups keep plugging away at new modifications—targeting everything from room-temperature conductance to biodegradability. Early worries about price and accessibility faded as improved synthesis methods dropped costs per gram, bringing new iterations into the sights of smaller research labs and high school STEM programs. Research papers now critically compare imidazolium bromides, tweaking tail length, ring substitutions, and counterions to optimize properties for specific jobs. My own favorite project found success switching between imidazolium and pyrrolidinium cores to eke out extra electrochemical stability, proving that even well-established structures have untapped potential when approached creatively.

Toxicity Research

Toxicology on ionic liquids still serves up more questions than answers. Short-term studies on 1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium Bromide suggest its acute toxicity sits lower than that of classic industrial solvents, but chronic effects, especially in soil and water, need long-term attention. Lab accidents haven’t led to dramatic consequences yet, but the persistent, poorly biodegradable nature of these compounds means downstream consequences could emerge, especially as usage scales. Responsible companies have started funding environmental fate studies and exploring structural modifications—searching for ways to balance industrial need against environmental stewardship. More independent review, and probably new international guidelines, will matter as the chemical slips further into industrial processing streams and potentially public water systems.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, scientists, companies, and regulators confront both excitement and tough choices. 1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium Bromide’s profile sets it up for expanded roles in greener manufacturing, more efficient batteries, and smarter separation processes. Wide adoption depends on resolving the production cost equation, guaranteeing occupational and environmental safety, and staying ahead of regulatory demands. As teams innovate on both the chemistry and how they communicate risks, broader use in industry and research seems likely—especially if fundamental science continues to bridge the knowledge gaps. The future looks bright, but constant vigilance and investment will be essential to keep this sophisticated tool as clean and safe as its promise suggests.

A Closer Look At Applications

Walking into a lab, you’d be surprised by how many roles a single chemical can take up. That’s the deal with 1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium Bromide. Most people outside chemistry circles won’t recognize the name, but in the right hands, it’s a bit of a workhorse. Chemistry isn’t just about mixing things for fun; it’s about creating tools for science, health, and sustainable technology.

The Power of Ionic Liquids

This stuff falls into a group called ionic liquids. They don’t evaporate the way water or gasoline does, so working with them in the lab means less fumes escaping into the air. That makes them a favorite for folks who don’t like masking up all the time or dealing with complicated ventilation. Scientists love 1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium Bromide because its structure lets them play around with solvents and try new reactions without worrying about old-school hazards each step of the way.

Tough Problems in Extraction and Separation

In the world of chemical extraction, getting pure materials out of messy mixtures pushes the limits of what is possible. That’s where ionic liquids come in strong. Extracting heavy metals from wastewater, separating complex organics, or recycling rare earth elements get a huge boost from this type of compound. Water treatment plants, for instance, often fight to remove poisonous metals without generating toxic byproducts. 1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium Bromide shows promise as an alternative to harsher chemicals in these roles. Research papers have highlighted lower energy use and successful heavy metal removal using similar structures.

Innovation in Electrochemistry

Tech keeps demanding more from batteries, supercapacitors, and fuel cells. Electrolytes are the blood of these devices, shuttling ions back and forth. Stable, high-performing ionic liquids make the whole system safer and longer-lasting. Battery specialists and engineers use 1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium Bromide to test performance improvements and cost savings. The results sometimes speak for themselves: some lithium-ion prototypes running on these liquids show greater stability and lower chances of overheating compared to old models. As electric cars roll off the line, safer and more efficient electrolytes mean less risk for drivers and fewer replacement cycles clogging up recycling centers.

Potential for Greener Chemistry

I spent several years in academic research, hunting for greener ways to make specialty chemicals. During that time, the sustainability question weighed heavy. Ionic liquids entered conversations about reducing pollution and conserving resources. 1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium Bromide isn’t magic, but it’s helping move industrial labs away from solvents that pollute waterways or wreck the air. It won’t fix everything—the process to make these chemicals uses energy, and end-of-life treatment still needs more study. Looking at the big picture, the industry benefits by replacing volatile, dangerous liquids with safer alternatives whenever possible. Small steps can mean better health for workers and fewer accidents.

Seeking Practical Solutions

For anyone tasked with solving today's manufacturing, water treatment, or battery challenges, 1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium Bromide offers a useful option. Bringing lab results into the real world always hits a few speed bumps. Questions about cost, disposal, and lifecycle impacts need honest answers before scaling up. Teams with experience in both research and industrial practice can keep pushing boundaries, making small moves toward safer, more efficient tech. That’s a future I’d like to see more companies build toward, one well-tested molecule at a time.

A Closer Look at the Chemical Skeleton

1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium bromide isn’t a household name, but its chemical makeup carries plenty of weight for those studying ionic liquids. The heart of the structure hinges on an imidazolium ring—a five-membered ring holding two nitrogen atoms. Stick two tetradecyl groups (each one delivering a fourteen-carbon chain) onto the ring’s 1 and 3 positions, and pair the whole thing with a bromide ion to balance the charge. Now you’ve got a molecule whose stretched-out alkyl tails bring more than just length—they change the story entirely compared to simpler imidazolium compounds.

The Fatty Tails Make the Difference

Long alkyl chains do more than just bulk up the molecule. Folks in the lab notice these chains boost the hydrophobic character and melt the boundaries between chemicals usually kept apart. In my grad school days, I messed around with ionic liquids like these. Handling them, you can smell the faint waxy odor, see the way these liquids stay slick and refuse to bead up with water. The long tails break up crystal packing, lowering melting points and making the liquid flow at room temperature. That unique behavior has practical value—chemists pick ionic liquids like this for their low volatility and stability, which keeps them from fizzing off or breaking apart under harsh conditions. That’s not just slick lab chemistry; it opens the door to safer, more efficient industrial reactions.

Applications That Rely on Structure

People sometimes overlook just how much a molecule’s shape matters. 1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium bromide gets tapped for extraction, catalysis, and even anti-microbial work, and this only happens because the long chains make it both oil- and salt-loving. You can separate out heavy metals, pull dyes from water, or coax a tricky reaction to run in water-free conditions. The bromide part pairs up easily, helping shuttle charges in electrochemical setups or keeping things balanced in separation processes.

Evidence Supports the Benefits

Researchers at universities and big chemical companies keep putting these ionic liquids through their paces. Peer-reviewed studies point to lower vapor pressure (meaning spills and fumes matter less), reduced flammability, and great reusability. Some groups even found that 1,3-ditetradecylimidazolium bromide can pull out environmental contaminants more efficiently than old-fashioned solvents. Numbers from these studies show extraction rates often climb by 20-30 percentage points compared to standard organic phases, which could mean a real step forward for greener chemistry.

Challenges and Potential Paths Forward

No chemical comes without worries. Some ionic liquids tend to linger in the environment rather than break down cleanly. Those long alkyl chains help performance, but they slow down natural degradation. Researchers are working out ways to tweak the side chains so the molecule keeps its special properties but doesn’t hang around where it doesn’t belong. I’ve heard from colleagues in environmental labs that substituting in more biodegradable tails helps, but it’s tricky: push too far, and you lose the very features that made these molecules appealing in the first place.

Building Toward Smarter Chemistry

The story of 1,3-ditetradecylimidazolium bromide shows how chemical structure guides real-world results. Long hydrocarbon chains change more than physical characteristics—they set up new opportunities and bring new challenges. Ongoing research, collaboration between chemists and environmental scientists, and better testing all shape how these ionic liquids will evolve in labs and industries. Structure tells the story, and every new tweak writes a new chapter.

Getting to Know the Substance

Working in labs long enough, you start to get a sense that chemical bottles aren’t just supplies—they’re responsibility. 1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium Bromide might sound like something only a specialist touches, but its quirks land it squarely in the real world of chemical safety. The compound, an ionic liquid, shows up in research thanks to its unique properties. Folks use it in things like catalysis and as a solvent for tough-to-dissolve compounds. Once that bottle arrives, though, how you store it shapes both safety and the quality of future work.

The Real Risks Beneath the Lid

This isn’t table salt. Ionic liquids can hit sensitive skin, eyes, and lungs. Mistreatment could spoil the compound or put staff at risk. I’ve seen researchers lose whole samples from ignoring basic guidelines. In one project, a colleague set a similar compound on a window ledge in direct sunlight, figuring it would “be fine.” After two weeks, the liquid had yellowed, moisture leaked into the vial, and what was left wasn’t usable for precision research. All that work, wasted. That’s not only frustrating, but also expensive, and sometimes dangerous.

Rules for Safe Storage

Start with a cool, dry place. Most manufacturers suggest temperatures below 25°C. Heat can degrade many ionic liquids. Sunlight streaming through lab windows becomes a real problem. Avoid windows and keep bottles on lower shelves in cabinets or chemical fridges. Humidity is another headache. Moisture from the air can creep in every time the bottle opens, since this substance tends to pull in water from the air. Tightly sealed containers with screw caps and a layer of parafilm keep out that unwanted dampness.

Labeling matters too. It’s tempting to jot down a shorthand or rely on memory, but mix-ups happen. Heavy penalties for mislabeling reflect how a tiny slip can turn into a big mistake. Add the compound name, concentration, date of receipt, and hazard information, then double-check before you set the bottle away. If you handle multiple similar imidazolium salts, keep them apart to avoid confusion and to help in emergency situations.

One of the smartest routines in a well-run lab calls for Safety Data Sheets to sit right near work benches and storage areas—no one should rummage through drawers looking for handling tips during a spill. Reading the SDS tells you quickly what can go wrong and how to act fast. For this compound, the risk of inhalation exposes you to irritation and things get worse if the powder becomes airborne.

The Value of Well-Drawn Boundaries

Lock away unfamiliar chemicals in cupboards. No undergraduate or visitor should pick up an imidazolium salt without a supervisor’s nod and protective gear—goggles, gloves, lab coat. I’ve learned over years that rules like this don’t just slow people down—they keep accidents out of journal articles and frontline news. Some labs log every vial in and out, which helps trace mistakes before they spread.

Turning Policy Into Habit

The idea isn’t to shelter 1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium Bromide behind glass forever. Good storage policies simply make the lab a safer place for serious science. Reliable routines, like daily checks for leaks and regular cleanouts, stay with you long after that particular project wraps up. In the landscape of chemical storage, a few steps—cool temp, closed lid, readable labels—protect budgets, research, and people. That’s just good lab sense, confirmed by the experiences others have had before you.

Understanding the Chemical and Its Real Risks

Chemicals with complex names often push people away from giving them a second thought, yet ignoring what’s in our environments makes room for trouble. 1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium bromide might sound like just another lab concoction, but some people have good reason to care about whether it poses a risk to human health or the environment.

This compound belongs in the family of ionic liquids. Scientists prize these for unique properties, especially in greener industrial processes or as solvents that don’t evaporate easily. People looking for sustainable chemistry may feel drawn to these liquids since they don’t produce much vapor, which in theory should reduce workplace exposure to harmful fumes. But lower volatility doesn’t always mean a chemical is safe for people, nor for nature.

How Hazardous Is It Really?

The research story on 1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium bromide isn’t as deep as with the most famous hazardous chemicals, so drawing conclusions takes some detective work. Other chemicals in the same family—imidazolium-based ionic liquids—don’t have a totally clean record. Some studies indicate these kinds of compounds can hurt aquatic life, damaging cell membranes and causing problems for fish or tiny water creatures.

I’ve spent time in research labs with ionic liquids and learned to respect the guidance given for handling them, even if the air didn’t fill with sharp odors like with old-school solvents. Gloves and careful disposal remain the norm. Some reports suggest these chemicals can be toxic to human cells, causing irritation or even interfering with cell health after long exposure. That matters for people who spend time around them, whether in industrial jobs or academic work.

According to safety data from suppliers, 1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium bromide often earns warnings about skin and eye irritation. Not as alarming as classic toxins, but not to be brushed aside either. Touching the compound or breathing in dust can cause problems for people with sensitive skin, and it can trigger lung discomfort if mishandled. Unfortunately, gaps in public data slow down full risk assessment; regulatory agencies haven’t put this compound through as many hoops as they did with older, more widespread chemicals.

Why Transparency and Research Matter

The conversation about 1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium bromide ties into bigger challenges with chemicals society uses every day. Once a substance leaves the lab and starts showing up in more products or processes, accidental spills and waste disposal become bigger concerns. The planet’s water systems tend not to forgive mistakes easily; many ionic liquids can persist without breaking down, putting fish and ecosystems at risk if companies handle waste carelessly.

Better research and stricter disclosure would help. Full, public safety testing shines light on how dangerous a chemical might be. Workers and communities both need clear guidelines, not wishful thinking or gaps in knowledge. Relying on safety data sheets remains the baseline, not the gold standard. Regulators, chemists, and industries need to stop playing catch-up with emerging hazards.

Taking Steps Forward

People working with specialized chemicals should face the facts, not just grab gloves and hope for the best. Regular health monitoring, spill training, and conversations about alternatives can all push companies to make more responsible decisions. For regulators, first looking for evidence, sharing data widely, and demanding more thorough toxicity studies would protect workers and environments. Transparency wins out over warnings buried in technical documents. The story of 1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium bromide reminds everyone that just because a risk hides behind a complicated name, it doesn’t make it less real.

A Day in the Life of a Quaternary Salt

1,3-Ditetradecylimidazolium bromide doesn’t have the flashiest name, but it sure gets attention in the lab. This compound belongs to the ionic liquid family, with the imidazolium core known for its bulky, paired-up hydrocarbon chains. My first encounter with it came in a project focused on stabilizing emulsions for a biotech startup. It all started with that striking mix: a charged imidazolium head sitting between two hefty tetradecyl chains, matched to a small bromide anion.

Pull this powder off the shelf and put it in water, and you’ll notice two things right away. The imidazolium part loves water because it carries a positive charge, but those long tetradecyl tails do not want to play along. They’d much rather hover around other oily or nonpolar stuff, making the compound practically insoluble in cold water. I remember stirring it vigorously at room temperature—nothing budged. Eventually, you end up with cloudy water and undissolved solid. If you bump up the temperature, you might coax a smidge more into solution, especially if you agitate the mix or add co-solvents.

The Oil-Loving Nature

Those hydrocarbon chains flip the script in nonpolar solvents. Place a pinch into hexane, chloroform, or even toluene, and the compound acts like an old friend—readily dispersing without much fuss. In practice, this means it gets used as a surfactant or phase transfer catalyst, especially if you want to bridge water and oil phases. The imidazolium head holds onto ionic or polar targets, while the tails grab fat-soluble molecules. In my own experiments with surfactants, 1,3-ditetradecylimidazolium bromide helped wrangle together phases that just don’t want to blend. The result? Stable emulsions in oil-rich formulations, from cosmetics to specialty lubricants.

If you try dissolving it in alcohols, you’ll find a middle ground. Ethanol and isopropanol do a decent job—a clear solution forms with some patience. That solubility comes in handy if you’re trying to prepare stock solutions or work with organic extractions, because you can mix and match solvent power to match a task.

Think Before You Mix

As much as folks chase the versatility of these ionic liquids, real applications demand a closer look at these interactions. For example, waste streams from processes using 1,3-ditetradecylimidazolium bromide can end up clogged with residues because of incomplete dissolution in water. Years ago, a colleague watched pipes plug up because a little too much was dumped down the drain without proper dilution.

Safer handling starts with treating these compounds with the same respect you offer strong detergents. It’s always tempting to crank up concentrations to drive a reaction forward, but the low water solubility makes accurate dosing critical. Labs working with lots of surfactants use gentle mixing, warm temperatures, and, where possible, pre-dissolving in alcohol or acetone to avoid blockages.

A good practice—one I learned the hard way—is to consult the full solvent compatibility chart before setting up a reaction. Not all ionic liquids behave like 1,3-ditetradecylimidazolium bromide, but the long tails on this compound make it much more at home in the oily, nonpolar world. For researchers, this property isn’t just a chemical curiosity. It shapes how materials get selected for reactions; it determines storage and cleanup steps, and it highlights the value of matching solvent and solute early in any workflow.

Small Fixes, Big Difference

If it has to go in water, blend with detergents that match the tail structure. Mild surfactants can pull these molecules into solution more effectively, preventing buildup in waste lines and instruments. In industry, closed-loop recovery systems allow spent ionic liquids to be captured, filtered, and reused. These strategies save money, but more importantly, they keep unwanted residues from causing headaches down the line.

Understanding the solubility of 1,3-ditetradecylimidazolium bromide turns guesswork into good science. Simple habits—warming, mixing, and matching with the right solvents—make this quirky compound a tool worth mastering, not a stumbling block in the lab.