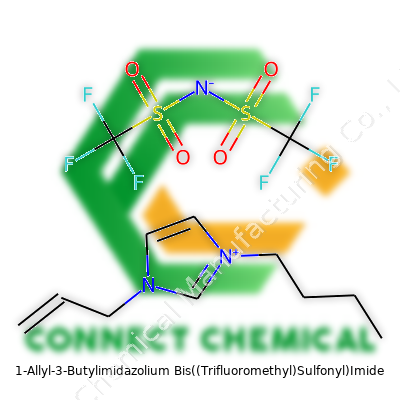

1-Allyl-3-Butylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide: A Deeper Look

Historical Development

1-Allyl-3-Butylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide, known to a handful of specialists as [C4C3Im][NTf2], stands on the shoulders of decades of ionic liquid research. The push for green chemistry in the late twentieth century spurred chemists to look for alternatives to toxic organic solvents. The imidazolium class, at first just a curiosity, picked up steam as researchers needed tunable fluids for electrochemistry and catalysis. By the time [C4C3Im][NTf2] emerged in the literature, the focus shifted from “can we make it?” to “what can we do with it?” I remember seeing its use in fluorous biphasic systems as a sign that ionic liquids had moved from obscure benchwork to real tools for innovation.

Product Overview

This compound combines an imidazolium cation—decorated with allyl and butyl groups—and the large, stable bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide anion. It shows off what makes ionic liquids so useful: chemical and thermal stability, low vapor pressure, and broad solvation ability. Researchers order it for its remarkable balance of hydrophobicity and ion conductivity. In my work, I found it particularly handy for electrodeposition trials because it blends ease of handling with electrochemical reliability.

Physical & Chemical Properties

The physical nature of this ionic liquid stands out even among peers. A clear, colorless to faintly yellow liquid at room temperature, it clings to glassware with a slight viscous drag. Its density hovers near 1.34 g/cm³, and it refuses to evaporate under standard lab conditions, dodging the inhalation risks associated with more volatile organic solvents. I’ve seen chemical resistance here: it handles organic reagents without breaking down, owing to that robust NTf2 anion. It’s non-flammable, a relief in any lab with open flames or hot plates. The melting point lingers well below room temperature, underscoring its status as a “room temperature ionic liquid.”

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Labs receive it in small bottles sealed tightly to lock out moisture. Purity, often at or above 99%, stays listed on the certificate of analysis alongside key specs: water content below 500 ppm, halide impurities negligible, and residual solvents clearly identified. Sometimes, a brief run of NMR and IR spectra accompanies each lot, satisfying the need for traceability and reproducibility. Regulatory labels flag its status as a chemical for research use only—never food or drug ingredient, a rule many have learned the hard way from previous solvent mishaps.

Preparation Method

Synthesis doesn’t follow a single recipe. Most researchers start with 1-butylimidazole and allyl chloride, using a well-managed alkylation to generate the cation precursor. Metathesis with lithium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide in water or a polar organic phase swaps out halide for NTf2. Washing, drying over vacuum or phosphorus pentoxide, then fine filtration gives a product clean enough for analytical or preparative chemistry. For years, I’ve told students to distrust short-cut methods here: water or halide contamination haunts sensitive applications.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Resistance to decomposition marks its real strength. The imidazolium ring tolerates mild acids and bases, but nucleophiles target the allyl group under strong enough conditions. Substitution at the allyl or butyl positions tunes physical properties; for instance, switching butyl for pentyl boosts hydrophobicity, which can be useful in two-phase reactions. Surface chemists often immobilize this ionic liquid onto silica or carbon, crafting tailored interfaces for sensors or catalysis. Its broad stability window helps push electrochemical research past what water or acetonitrile can offer.

Synonyms & Product Names

You might spot this compound listed as 1-Allyl-3-butylimidazolium NTf2, [C4C3Im][NTf2], or even just “ABIM NTf2” in some catalogs. Suppliers each stamp their code on it, but CAS Number 396088-13-2 tracks it across the globe. The “ionic liquid” banner covers dozens of related materials, yet this one keeps a loyal following among those focused on tailored solvents or battery electrolytes, even as new salts attract the spotlight.

Safety & Operational Standards

Even stable chemicals demand respect. Gloves and eye protection come out every time the bottle opens. Spills feel slick but not caustic; still, prolonged skin contact brings risk of irritation. The NTf2 anion resists hydrolysis, but avoid heating to decomposition—fluorinated breakdown products rarely end well for breathing space. Waste heads to halogenated organic disposal, not down the drain. I’ve found most risk here lies in scaling up—a little confusion with less benign sulfonyl imide salts causes big headaches, so labeling and clean storage matter.

Application Area

Researchers gravitate to this ionic liquid for serious reasons. It thrives in non-aqueous electrochemistry, giving both high conductivity and stability across wide voltage ranges. Some in my network use it for gold or platinum electrodeposition, while others see value as an extraction solvent for rare earth metals. The balance of hydrophilic cation and hydrophobic anion creates opportunities in both catalysis—in reactions like CO2 reduction—and as a non-volatile additive for lubricants where temperature extremes challenge mineral oils. Some biomolecular work uses this solvent to support enzyme catalytic activity that falters in water, showing the flexibility across disciplines.

Research & Development

Development pushes in two directions: greener production and broader application. Industry now wants synthetic routes that shave off toxic precursors or tricky purifications. On the application side, battery and supercapacitor designers target this ionic liquid for next-generation devices, hoping the high electrochemical stability delivers safer, longer-lasting cells. I keep seeing new blends—mixing ABIM NTf2 with urea or phosphonium salts to enhance certain electrolyte properties. Besides electronics, work on capturing atmospheric gases or breaking down persistent pollutants highlights how research refuses to stand still with a proven compound.

Toxicity Research

Years of study teach hard lessons. Imidazolium compounds rarely break down quickly in the environment, so persistence demands careful waste handling. Oral and dermal toxicity sit lower than many solvents, but not harmless—repeat exposure raises risk of liver and kidney stress in animal studies, and aquatic organisms show sensitivity at low concentrations. This evidence nudges teams toward closed-loop systems and mandates strong labeling in storage. I’ve walked through more than one safety training session focused on personal and environmental responsibility with ionic liquids; the story rings true for every new research hire.

Future Prospects

Chemistry continues to chase ionic liquids with new eyes. The growing push to electrify transportation—and with it, to stabilize high-performance batteries—puts ABIM NTf2 and its cousins in the spotlight. Product designers seek blends with other salts to adjust viscosity or boost ion transport. Green chemistry advocates focus on reducing the carbon footprint and environmental persistence, aiming for new synthesis methodologies that pull from renewable feedstocks and deliver easier end-of-life degradation. As regulatory frameworks tighten for persistent organic chemicals, labs and manufacturers adapt. Experience says nothing stands still: those who experiment, document, and adjust move the whole field forward, one vial at a time.

Electrolytes: The Quiet Powerhouse in Batteries

Batteries keep life humming along, from smartphones to electric vehicles. The word “electrolyte” may not raise eyebrows at a dinner table, but it sure keeps engineers busy. 1-Allyl-3-butylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide—most call it [ABIM][Tf₂N]—gives researchers another tool for building safer, longer-lasting batteries. It doesn’t dry out under heat, and doesn’t catch fire easily, two things that keep both insurance agents and customers happy. The wide temperature stability and super-low volatility mean a battery with this electrolyte won’t throw a fit in a hot car. In labs where researchers break down next-gen lithium batteries, ABIM-based ionic liquids show better conductivity than old-school solvents. Some studies report lithium transport numbers higher than classical electrolytes and, in turn, batteries that keep going charge after charge.

Green Chemistry Isn’t Just a Buzzword

More companies want both innovation and less pollution. Solvents often escape in clouds of vapor, sometimes causing health and environmental headaches. Ionic liquids like ABIM avoid much of this—almost no vapor pressure, so nothing leaks out into the air. Many chemical reactions need solvents that can take the heat, literally. ABIM stands up to the challenge, which opens the door for use in catalysis, including alkylation and acylation reactions. Compared to traditional organics, these salts work at high temperatures without breaking down, and waste treatment becomes less complicated. In my lab years ago, switching from volatile solvents to ionic liquids cut down on headaches—both literal and bureaucratic.

Separations and Extractions: Cleaner Solutions for Big Challenges

Separating chemicals is a daily hurdle for the chemical industry. Whether plucking sulfur out of diesel or grabbing heavy metals from wastewater, ABIM-based ionic liquids bring flexibility and efficiency. One team at a university I visited used ABIM in pilot tests for stripping lanthanides out of mining tailings, which made recycling rare earths a bit less daunting. Because these liquids don’t dissolve in water but welcome organic materials and some metals, companies use them for tough separations. Even pharmaceutical makers are joining in, swapping outdated, tough-to-recycle solvents for something reusable and less toxic.

Lubricants for Extremes

Running machinery hard, especially where standard oils fall apart, demands stronger stuff. ABIM serves up lubricants that keep parts moving in spots where regular greases burn up or freeze. These next-gen fluids last longer, resist fire, and don’t foul up gears. In steel factories, rail yards, or even research reactors, switching to ionic liquid lubricants means fewer failures. Staff can spend less time breaking out wrenches and more time pushing production.

What’s Next?

1-Allyl-3-butylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide is far from a household name, but its reach keeps growing as industries search for cleaner, tougher, and smarter materials. Some challenges loom: price tags and handling requirements can hold up mass adoption. Scaling up production methods, improving recycling, and ensuring worker safety during handling could help tip the balance. Stronger research partnerships between companies and universities are already charting new uses, and if companies get costs down, the jump to widespread use could happen sooner than anyone expects.

Understanding Chemical Stability

Chemicals have personalities of their own. Some stay put for years, barely changing a bit, while others seem eager to react with anything they touch. In the world of chemicals, stability doesn’t just affect shelf life—it directly impacts safety and product performance. From the lab bench to the warehouse, every handler wants peace of mind, knowing that what's in the bottle today won’t turn into something unexpected tomorrow.

Real stories from workplaces reveal more than any manual. I’ve seen cleaning agents lose strength in a month because they sat near a sunny window. Lower quality hydrogen peroxide turned yellow and fizzled early after being stored in a warm storeroom. On another occasion, a supposedly “inactive” raw material corroded metal shelves in a humid room. Mistakes happen fast without attention to detail.

What Affects Stability Most?

Light, temperature, humidity, and container compatibility play the biggest roles. Most chemicals prefer life in the shade, far from sunlight. Ultra violet rays are notorious troublemakers, leading to broken bonds or unwanted byproducts. Direct heat speeds up reactions, inviting decomposition or evaporation. High moisture causes problems for powders and salts, clumping them or even triggering slow reactions with the water in the air.

The packaging matters just as much. Glass beats most plastics for keeping strong acids and solvents safe. Stainless steel stores hydrogen peroxide better than aluminum. With volatile substances, loose caps or cracked seals spell disaster. Even a slow leak changes concentration over time. These aren’t just technicalities; they're lessons earned from ruined products and real costs.

Smart Storage Steps

Good storage starts with simple routines. Check the label before opening anything. If it says “store below 25°C,” that instruction exists for a reason. Manufacturers run tests that give solid guidelines. Flammable liquids never belong near a heat source or stove. Chemicals that react with air—like sodium hydroxide pellets—survive longer in tightly closed containers with silica gel packets or inert blankets like nitrogen gas.

For families of chemicals thought to be stable, routine inspections still pay off. Look out for color changes, gas formation, pressure in the bottle, or foul smells. Changes don’t lie. Most spills and accidents happen when workers get overconfident, trusting memory rather than reading storage charts or MSDS sheets.

Why It Matters in the Real World

Ignoring storage rules shortens the lifespan of expensive raw materials, sometimes making them unusable. In medicine, improper storage means lost potency or contamination, risking patient health. In food manufacturing, oxidized or spoiled additives can lead to safety recalls. Farmers know that the right pesticide does its job only if it keeps its punch from storage room to field. Even at home, a bottle of bleach left in the trunk of a hot car loses its effectiveness and turns into salted water.

Companies and individuals can sidestep most trouble with a handful of habits—reading instructions, keeping chemicals apart based on class and compatibility, and maintaining cool, dry storerooms. Regular training helps everyone spot trouble early. Good logs and rotation keep stock from expiring at the back of the shelf. Fireproof cabinets for dangerous chemicals are an easy upgrade and not just a checklist requirement.

Building Safer Habits

Manufacturers bear responsibility, offering guidance with every product. They back up their storage advice with field-tested stability data. Users, in turn, see better results, save money, and prevent shelf-life surprises. Trust in a product comes from this shared commitment. Keeping things simple—cool, dry, dark, sealed—wins out over shortcuts every time.

Diving Into the Compound

Working in a chemistry lab for several years, I’ve crossed paths with all sorts of ionic liquids. The one in question, 1-Allyl-3-Butylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide, often pops up in research, mostly thanks to its stability, ability to dissolve many substances, and use in electrochemical systems. It’s colorless or pale yellow and doesn’t give off much odor, so it’s easy to forget you’re handling something with real risks. Unfortunately, it’s not the friendliest compound in the cabinet.

What Science Shows Us About Toxicity

This chemical doesn’t belong to the same household hazard league as bleach or gasoline, but it should never be underestimated. Research suggests that many imidazolium-based ionic liquids are toxic, particularly if they come into contact with skin or if fumes get inhaled. For 1-Allyl-3-Butylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide, studies point out that the trifluoromethylsulfonyl group adds to environmental and biological persistence, raising red flags for aquatic environments and for repeated human exposure. Animal studies on similar compounds indicate potential for liver and lung damage at moderate-to-high doses and cellular disruption even with mild exposure over time.

Hazards Beyond the Lab

Think about the impact if careless disposal or spills happen. This compound does not break down quickly. That means trace amounts might stick around in soil or water, eventually affecting plants, microorganisms, or wildlife. Too many times, people focus only on personal danger—skin irritation, respiratory discomfort, eye injury—forgetting that the real cost often comes later and farther away, in riverbeds or crops that we all share.

Worker Safety and Best Practices

Whenever I handled chemicals like this, gloves and goggles were only the start. I made sure the workspace had good ventilation, and I kept spill kits close at hand. The US Occupational Safety and Health Administration doesn’t list a specific exposure limit for this ionic liquid, but the rule of thumb is clear: “Treat all as harmful unless proven otherwise.” Pragmatically, this means using a fume hood, never eating in a lab or production area, and avoiding skin contact. After seeing more than one colleague land a trip to medical for careless lab habits, I never skip hand-washing or safety gear, no matter how routine the task appears.

Environmental Responsibility and Solutions

Factories and research facilities that use this compound owe it to their workers and everyone downstream to handle disposal with care. Incineration at approved sites, sending waste to professional chemical disposal vendors, and employing closed-system technology can dramatically reduce environmental leaks. It’s important to push for greener alternatives whenever possible. Some labs turn to task-specific water-based mixtures and biodegradable solvents, but research lags far behind application demand.

Shared Accountability

Regulators, employers, and researchers play a big part in keeping people safe, but plenty of responsibility lands on the technician or researcher’s desk. Don’t shortcut steps for comfort or convenience. Safety data sheets might seem dry, but ignoring them ends badly. I’ve seen too many spills and near-misses from overconfidence. Stay vigilant, ask questions, and refuse to cut corners. Collective safety depends on each person doing their part, every day.

Why Purity Really Matters

Anyone who’s worked with chemicals on a regular basis knows that purity isn’t some minor technical detail. In the world of fine chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and even everyday products, purity tells you how confident you can feel about what’s in that bottle. Years ago, I ran into trouble with a supposedly pure reagent that, in reality, had traces of something else. That misstep wasn’t cheap. Whether in medicine or in materials science, contaminants can lead to big problems and expensive setbacks—nobody wants a failed product run or, worse, harm to customers.

Common Purity Grades Across Industries

Purity levels say a lot about what you can expect when using a compound. In the pharmaceutical field, “USP grade” guarantees a tight specification, usually above 98-99%. Food-grade chemicals, while also clean, tend to focus more on what is safe for people to eat, which often lands in the 95-99% range depending on the compound and its intended use. In the electronics world, trace metals or chemicals can hit 99.999%—those last few zeros make all the difference if you’re making semiconductors and can’t risk even a speck of contamination.

Lab supply companies, from Sigma-Aldrich to Merck, list out purity levels on every product page. Analytical standards reach 99.9% or higher, while technical-grade chemicals might come in below 90% pure. The information isn’t just for paperwork; it lets chemists choose the right balance of performance and cost. No one wants to pay high prices for high-purity chemicals where lower grades would do the job.

How Purity Gets Measured

Purity isn’t just a marketing claim; it gets verified in the lab with real data. Methods like chromatography, titration, and spectroscopy sniff out impurities with incredible accuracy, reporting everything in simple percentage terms. Good manufacturers include a certificate of analysis, not just for regulatory compliance, but to give buyers peace of mind.

Some industries list detailed specifications beyond a single purity number—think water content, residual solvents, heavy metals, and specific byproducts. For example, API (active pharmaceutical ingredient) producers need to guarantee no more than a few parts per million of certain impurities, because safety and performance ride on those numbers.

Quality Control and Regulatory Pressure

Government rules shape these standards, especially in pharmaceuticals and food. Regulatory agencies—from the US FDA to EMA—don’t leave much room for creative interpretation. I remember the scramble in a project years ago when our supplier’s lot deviated just slightly from agreed specs; the result was weeks of delay during re-validation. Documentation builds trust and protects everyone in the process, from manufacturer to end user.

Challenges and Solutions

Some companies struggle to meet high purity standards, especially as raw materials fluctuate in quality. The answer often lies in investing in better purification techniques, training staff for careful handling, and choosing reliable sources. Open communication along every step of the supply chain helps catch potential errors before they cost time and money. At the end of the day, purity levels and specifications aren’t just numbers—they’re one of the most important assurances that what you’re using will work safely and as promised.

References available on request for specific compounds or industry standards.Taking a Closer Look at Ionic Liquids

People working in batteries and electrochemistry love to talk about the next big thing. Right now, ionic liquids have got plenty of engineers and researchers paying attention. Unlike traditional solvents, ionic liquids do not evaporate at room temperature. This matters a lot, especially for technology trying to break free from the flammable or toxic mixtures that show up in older battery systems. The first time I handled an ionic liquid in a lab, I remember how odd it felt — oily, heavy, almost like a liquid salt. Yet there’s something special about these substances beyond their feel.

Why Safety and Stability Matter

Anyone who has seen a lithium-ion battery catch fire knows the worry is real. Household electronics, cars, even grid storage reflect this problem. Electrolytes based on organic solvents often create risks because they ignite under heat or short circuit. An ionic liquid doesn’t burn so easily. In everyday use, that property means devices keep going safely. This feature pushes scientists to consider ionic liquids for safer electric cars and portable electronics.

Tackling Performance Challenges

There’s more at stake than just safety. Conductivity matters: you want ions to move fast inside a battery. A big complaint about traditional ionic liquids is that they feel sluggish compared to what people expect from commercial lithium-ion cells. The viscosity slows down the movement of charged particles, especially at lower temperatures. Researchers have tried a lot of tricks, adding small molecules or changing the ions themselves, to speed things up. Results keep improving. Today, some ionic liquids come close to traditional electrolytes, especially in high-temperature or specialized settings.

Handling the Cost Issue

Ionic liquids don’t come cheap. For years, this kept them locked in labs and out of factories. Companies focused on grid-scale storage or commercial vehicles weigh every ingredient by the dollar, not just by technical merit. Some newer types have gotten easier to make, dropping prices. Labs exploring recycling and green synthesis methods hope to close the gap further. If costs keep dropping, ionic liquids could fit into more markets and give companies enough reason to switch.

The Push for Sustainability

Replacing lithium-ion with greener choices isn’t just hype—rules are changing fast. Fossil-based solvents generate plenty of waste and hazards; regulators care. I’ve seen more research groups lean into ionic liquids because they make recycling and low-waste manufacturing possible. Add to that the resilience against water and oxygen, and you’ve got a pathway to batteries that handle rough or damp environments.

What’s Next for Electrochemistry?

Engineers want something reliable, safe, and affordable. Ionic liquids don’t win in every category yet, but progress happens quickly. Improvements in conductivity and cost open new doors. Collaborations between material scientists, battery makers, and recyclers keep pushing limits. Anyone watching this field closely will find practical applications — in sensors, in energy storage, and in electric mobility. Companies ready to experiment with new materials will shape how fast these changes arrive.