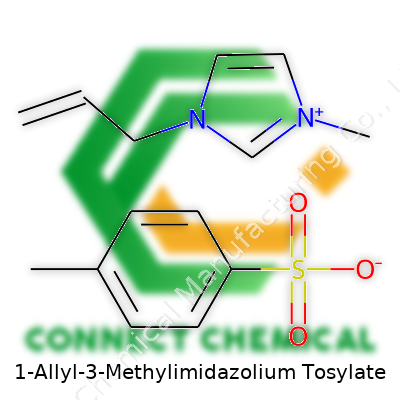

1-Allyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tosylate: A Commentary

Historical Development

Chemists have searched for alternatives to hazardous organic solvents since the late 20th century, kicking off a race for substances that would be safer, more versatile, and milder for both people and the earth. Their experiments pulled focus onto ionic liquids, compounds with unique properties untied from traditional solvent expectations. As researchers tinkered with imidazolium structures, they discovered that changing one atom could mean a big leap in performance. The introduction of allyl and methyl groups on the imidazolium ring, followed by pairing with bulky sulfonate anions like tosylate, generated dependable salts. These became especially popular among those pursuing green chemistry and sustainability.

Product Overview

1-Allyl-3-methylimidazolium tosylate, sometimes referred to as [AMIM][Tos], breaks from standard solvent behavior. This salt fits squarely within the ionic liquid family, classed by its low melting point and negligible vapor pressure. The heart of its value sits in its structure: an allyl group that spreads reactivity, a methyl group improving stability, and a tosylate anion that injects solubility and resilience. Years in the lab have shown it mixes with a surprisingly wide range of chemicals, handling everything from organic synthesis to serving as a medium in material formation.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Anyone who has handled [AMIM][Tos] remembers its slightly viscous, pale yellow to colorless liquid state at room temperature. Unlike volatile compounds, it holds its shape, resisting evaporation. Boiling isn’t practical under ambient pressure, so the liquid holds up under heating, making it easier to contain and reuse. Its density floats around 1.19 g/cm³ at 25°C, and with a melting point typically below 60°C the substance pours smoothly even on a laboratory bench. It conducts ions rather than electrons—very different from metal solutions—so it excels in applications demanding steady, mild conductivity. Thanks to its design, it also resists chemical breakdown in moderate to strong bases and acids, handling routine abuse both in academic and commercial labs.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Bottles of this compound must arrive with precise identification. Labels need to state the chemical formula: C13H16N2O3S, and often, the CAS number 366617-45-0. Purity rises above 98% in high-grade preparations, a detail that matters for reactions highly sensitive to water or trace metals. Hazard warnings for skin or eye irritation feature on all shipments, with safe handling guidelines detailed in shipment documentation. Some suppliers highlight compliance with the latest international transport and environmental rules, especially as regulations now track synthetic intermediates more closely.

Preparation Method

Synthesis routes for [AMIM][Tos] rarely stray from a key process. Start with 1-methylimidazole, react it with allyl chloride (an alkylating agent), and the resulting salt—1-allyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride—serves as the stepping stone. Next, mix with sodium or potassium p-toluenesulfonate in water. The cation exchanges the chloride for tosylate, prompting immediate precipitation or layering out of the product. Drying steps remove traces of water, and further purification by extraction or recrystallization sharpens the purity to fine margins. Years spent refining these protocols have made them reproducible, efficient, and suitable for scaling up from test tube to pilot plant.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

This compound tolerates a diverse set of reaction partners. Its ionic character dissolves a swath of polar and even some nonpolar compounds, acting as a medium for palladium-catalyzed couplings, alkylations, and nucleophilic substitutions. Modifications can be made at the allyl position, opening doors for further polymerization or cycloaddition. The imidazolium core itself can serve as a template for more exotic derivatives, like those tailored for enzyme stabilization or as custom phase transfer catalysts. Chemists have taken advantage of its stability against hydrolysis, so moisture-laden reactions don’t force early failure.

Synonyms & Product Names

This liquid goes by several synonyms on shipping manifests and technical data sheets. Besides 1-allyl-3-methylimidazolium p-toluenesulfonate, suppliers abbreviate it as [AMIM][Tos] or AMIM-TsO. While some niche sellers invent their own product codes, the established names anchor product searches. In publications, its chemical shorthand cues in professionals familiar with ionic liquids, upholding consistency across disciplines.

Safety & Operational Standards

Treating [AMIM][Tos] as a benign solvent courts disaster. Though less flammable than ethers or alcohols, the compound still stings if splashed on skin, and inhalation of mist or vapor from heated solutions can irritate airways. Wearing gloves, goggles, and working under a fume hood forms basic procedure. Proper waste handling requires segregation—never mixing ionic liquid residues with household solvents. Disposal must follow local hazardous materials guidance, as improper dumping threatens water sources and aquatic life. Some safety officers even press for routine respiratory monitoring for staff running frequent synthetic campaigns, especially where scale-up is involved.

Application Area

Chemists have pressed [AMIM][Tos] into varied duty. In organic synthesis, it steps in as a non-volatile solvent for stubborn palladium and copper-catalyzed reactions. Students in graduate labs often learn its quirks by running alkylation reactions or extracting natural compounds from plant matrices. Material scientists test its suitability for cellulose dissolution—crucial for developing films and fibers from natural sources. Electrochemists swap out classic salts in favor of this ionic liquid, especially to build stable, safe electrochemical devices. Biomedical research teams also mix [AMIM][Tos] with biopolymers to cast gels, spurring interest in tissue engineering and drug delivery vehicles.

Research & Development

Ongoing studies track exactly what makes this liquid tick, from ion pairing preferences to long-term stability in mixed solvent systems. Labs working with catalytic partners probe how subtle shifts in composition affect turnover and recyclability, aiming to trim waste even further. Material engineers are surveying composite materials containing [AMIM][Tos], betting on improved physical properties, or clever responsive behaviors. Global R&D hubs are connecting with environmental toxicologists to create safer ionic liquids, trying new structural tweaks in the cation or anion for trade-offs between performance and safety.

Toxicity Research

The absence of flammable vapors might ease early worries, but closer inspection has revealed some mixed news for [AMIM][Tos]. Acute toxicity in lab rodents isn’t sky-high, yet chronic exposures and aquatic toxicity spark concerns. Degradation byproducts in waste streams have put a magnifying glass on ionic liquid disposal. Comprehensive studies now examine effects on environmental bacteria, small crustaceans, and vascular plants. Academic journals regularly call for better metrics—half-life in real-world water bodies, bioaccumulation, and any capability to disrupt endocrine systems. Regulatory bodies in Europe and Asia demand fresh data before granting approvals for food-contact or pharmaceutical applications, holding the material to the same rigorous standards as other emerging industrial chemicals.

Future Prospects

Interest in ionic liquids like 1-allyl-3-methylimidazolium tosylate hasn’t peaked. New fields look set to stretch its reputation—battery researchers tap its conductive and thermal stability properties, while pharmaceutical scientists test its compatibility with cutting-edge drug delivery matrices. At the same time, green chemistry mandates push researchers to trim toxicity and improve biodegradability. Lately, synthetic biologists have started mixing this compound with enzymes, hinting at manufacturing routes for sustainable chemicals otherwise unreachable using standard solvents. Large-scale commercialization will still depend on driving down production costs and proving environmental wins stack up beyond the bench scale, shaping both regulations and incentives in the years ahead.

The Real Workhorse in Chemical Labs

Stumble into any chemistry lab focusing on green tech, and you’ll see bottles labeled 1-Allyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tosylate, or AMIM-Ts for short. This isn’t just fancy jargon. It’s an ionic liquid—a type of salt that stays in liquid form at room temperature. Instead of expecting it to behave like everyday table salt, think of it as a solvent that skips the flammable fumes or eco-issues that come with many classic solvents.

What Sets AMIM-Ts Apart in the Lab

I remember seeing the struggle to get cellulose from plants to dissolve for bio-materials research. Most chemicals failed, leaving behind half-processed gunk. AMIM-Ts steps in and manages to dissolve cellulose with surprising efficiency. Even tough-to-handle polymers like chitin or lignin, common in industrial waste, crack under its grip. Researchers count on it to break down these strong biopolymers, laying the groundwork for everything from smart packaging to biofuels.

Making Reactions Cleaner and Quicker

Lab work often deals with tradeoffs: speed, purity, safety. AMIM-Ts helps nudge things toward the better side. It isn’t volatile or flammable, which means less risk to people and the planet. With AMIM-Ts, catalysis—the art of getting molecules to react faster—takes on a greener profile. Cross-coupling reactions, essential in pharmaceutical breakthroughs, run smoother here because the liquid supports stubborn catalysts that stumble in standard organic solvents.

Packing a Punch in Separation and Extraction

Separating valuable chemicals from sticky mixtures often produces headaches and industrial waste. AMIM-Ts comes into play by pulling select compounds from soup-like slurries. This shows up in environmental labs, where people hunt for heavy metals in water samples. AMIM-Ts can grab onto these pollutants, clearing up solutions with fewer harsh chemicals. Less pollution up front means less trouble at cleanup time.

Helping Biomaterials Travel Further

Nylon and similar plastics set the standard for durability but create a landfill headache. Scientists working toward biodegradable plastics started using AMIM-Ts to dissolve and then recast cellulose into films, fibers, and sponges. This trick transforms waste like sawdust or paper pulp into useful stuff, making bioplastics a regular feature in shopping aisles instead of a quirky experiment.

Putting AMIM-Ts to Work in Energy

Screens and batteries depend on stable, efficient materials. The same properties that make AMIM-Ts good at dissolving plant matter turn out handy for making robust membranes in fuel cells. It carries charged particles without eating away the structure or corroding parts. As alternative energy picks up, AMIM-Ts helps push more reliable devices out of research and into the market.

Why We Should Care and What Happens Next

R&D spending on “ionic liquids” like AMIM-Ts traces back to a need for safer, more sustainable chemicals. It’s not perfect—price and recyclability leave room for improvement, and only a handful of companies make it at scale. Academic labs keep hunting for cheaper production methods and ways to recover the liquid after use. If costs drop and recovery tech improves, you might see this tongue-twisting liquid show up in everything from eco-friendly plastics to energy storage sooner than you’d think.

Why Ionic Liquids Matter to Chemistry and Everyday Life

Walk through any advanced chemistry lab and you'll notice a steady interest in ionic liquids. Many researchers prefer them over volatile organic solvents. These innovative compounds come with low vapor pressure and unique solubility profiles, making experiments less hazardous. As someone who’s spilled acetone one too many times, I appreciate solutions that work cleaner and safer. One ionic liquid that’s winning attention is 1-Allyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tosylate.

Breaking Down the Chemical Formula

Here’s what we’re looking at: the chemical formula for 1-Allyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tosylate is C13H18N2O3S. The salt forms from combining a cation (1-allyl-3-methylimidazolium) with an anion (tosylate, which comes from p-toluenesulfonic acid).

For students of chemistry, formulas assign purpose to every atom. C13H18N2O3S unpacks neatly as follows:

- C — 13 carbon atoms bring structure and backbone, both in the imidazolium ring and the tolyl group.

- H — 18 hydrogens fill out the rings and side chains, balancing the overall molecule.

- N — 2 nitrogens signal the imidazolium core, a hallmark of these ionic liquids.

- O — 3 oxygens reflect the sulfonate group from tosylate, which increases solubility.

- S — 1 sulfur atom, also part of the sulfonate group, key for charge balance.

On paper, this formula helps chemists communicate without ambiguity. I’ve seen researchers reference the shorthand in papers, then build on it to explore green synthesis methods or recycling processes.

Applications Bring Real-World Impact

1-Allyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tosylate isn’t just a string of letters. Labs and certain industries value it for dissolving cellulose, catalyzing reactions, and extracting bioactive compounds. Compared to old-school organic solvents, it avoids the headaches of flammability and stench. I once worked with a team extracting flavours from plant materials, and switching to this ionic liquid helped us cut both hazardous waste and cleanup time.

Consider one process: converting biomass into biofuels. Traditional solvents either don’t dissolve cellulose well or generate a lot of toxic byproducts. This is where ionic liquids, especially those based on the imidazolium framework, excel. Their chemical structure allows fine-tuned interactions with both plant fibers and enzymes.

Challenges and Solutions

Every new technology brings hurdles. High price points, inconvenient synthesis, and debates around long-term toxicity hold back widespread adoption. These are legitimate concerns. I’ve seen academic papers call out the need for greener, cheaper manufacturing routes. Regulatory bodies keep a cautious watch, especially when proposed uses touch pharmaceutical or food applications.

Solutions begin at the chemistry bench. Open sharing of synthetic protocols, process optimization, and recycling strategies can gradually bring down production costs. Life cycle analysis of these salts—tracking them from synthesis to disposal—helps head off environmental impacts. Public-private partnerships can speed translation from lab success to safe, scalable industry use.

Supporting Informed Progress

Clear communication around new materials matters. Fact-based discussion and peer-reviewed studies, not hype, build trust. Companies making the leap from volatile solvents to stable ionic liquids have a responsibility to openly share data. This improves workplace safety, environmental protection, and, most important, scientific understanding.

1-Allyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tosylate—formula C13H18N2O3S—stands as a good example of how practical chemistry and innovation can overlap. Proper stewardship and open information support the best results, for labs and for everyone who relies on cleaner tech.

Practical Concerns Around Storing Modern Ionic Liquids

Working in a lab, I’ve seen the disappointment that comes from poorly stored compounds. 1-Allyl-3-methylimidazolium tosylate belongs to a family of ionic liquids that promise a lot for green chemistry, electrochemistry, and organic synthesis. Carelessness with its storage knocks down its utility, so it’s worth honing in on clear and evidence-backed approaches to stashing this salt.

Why Moisture Protection Matters

Every chemist recognizes moisture as a persistent nuisance. This compound, with its ionic structure, pulls water from the air. Add a loosely capped bottle on a humid summer day and it turns sticky, possibly jeopardizing experiments or instrument components. Literature and manufacturer advice keep hammering on the same rule—seal it up tight. Glass containers with PTFE-lined caps do the trick for keeping out stray water.

From firsthand experience, a chunk of product left in a plastic flask under a standard fume hood turns clumpy within hours. This change isn’t just cosmetic. Water impacts melting point, reactivity, and often pushes you out of the ideal range for many syntheses. I’ve ruined more than a few GC-MS runs by overlooking these basics.

Temperature and Light: Avoiding Unwanted Reactions

Leaving 1-allyl-3-methylimidazolium tosylate at room temperature isn’t always smart, especially if the climate sways between hot and cool spells. I’ve let samples sit on a shelf right under a window. Within days, yellowing and even separation set in, probably from light and heat exposure. Store this salt in a temperature-stable spot, usually at or below 25°C. No direct sunlight, no radiant heat from the top of ovens, and certainly nothing close to heavy machinery that cycles warm and cool.

Handling and Accident Prevention

Open this jar in a dry box or with a stream of dry nitrogen running nearby, if you want to play it safe. A common mistake is pulling out the entire bottle for a brief aliquot, only to leave it exposed for ten or fifteen minutes as you run to get another tool. Weigh small amounts in separate containers whenever possible, and return the main stock to its spot as soon as you can. A trick I learned from my advisor: split large bottles into small working vials. This way, if one goes bad, you haven’t lost your whole supply.

Long-Term Integrity

Safety datasheets offer helpful benchmarks—keep the compound dry, cool, and shielded from unnecessary light, and you preserve its quality. Add silica gel packs to absorb any trace humidity if you plan on storing for months. Mark every bottle with the date opened, and every transfer gets a new label. This practice helped me avoid using degraded chemicals and keeps inventories honest.

Addressing Spills and Waste

Unlike old-school solvents, ionic liquids like this one pose less fire risk but require smart cleanup. A small spill calls for absorbent pads; bigger accidents mean a call to hazardous waste teams. Don’t rinse down the drain. Local disposal rules matter more than ever with synthetic salts, for both environmental and regulatory reasons.

Fact-Based Solutions Go a Long Way

Real chemical reliability starts with strong storage habits. Each container I’ve lost to degraded product taught me something that data sheets alone couldn’t cover. Get into the practice, keep things dry and cool, and both bench science and budgets improve. Ionic liquids offer new innovations, and care in their storage forms the backbone of that future.

Respecting the Chemistry

Lab work can be exciting, especially when diving into a compound like 1-Allyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tosylate. This ionic liquid opens doors in green chemistry, electrochemistry, and organic synthesis, but it also brings some risks you can't shrug off. Day-to-day use of chemicals shapes work habits; even in laid-back environments, a lapse causes real trouble. A strange smell or stinging skin drives home the point better than any safety poster.

Keeping Exposure Low

Touching or inhaling chemicals never ends well. The bigger issue isn't just spills—it's invisible vapors and traces left on glove cuffs. Skin contact with imidazolium salts sometimes leads to irritation or rashes. I remember a colleague forgetting to change gloves between tasks, which spread chemicals onto door handles. Folks learned to treat all chemical residues as a threat, not an afterthought.

Gloves rated for chemical resistance matter. Nitrile gloves work well for short tasks, but long exposure demands thicker gloves or double-gloving. Splash goggles should cover eyes snugly, not dangle loosely below the eyes. Fume hoods don’t only trap nasty solvents, they protect lungs from ionic liquids' slow-evaporating molecules, which build up in the air over a few hours.

What Happens with Spills?

A little care in setup prevents the worst headaches. Plastic trays or absorbent pads under glassware catch drips before they travel. If liquid hits the bench? Grab a spill kit and focus on ventilation—get the hood running high, windows open if allowed, and warn anyone working nearby. Toss any rags or towels used for cleanup in a waste bin marked "hazardous," not the regular trash.

Any sign of respiratory issues or skin burning calls for stopping work and heading straight to the eyewash or safety shower. Seek medical attention—don’t try to tough it out. It only takes one stubborn chemist passing out before the team adopts stricter procedures.

The Right Way to Store and Dispose

Store the chemical in tightly sealed bottles, away from acids, bases, and sunlight. Sunlight degrades these salts and can lead to pressure buildup in the container. Stack containers on lower shelves to limit falling hazards, and label everything with the name, date, and hazard warnings.

Waste disposal shouldn't involve pouring leftovers down the sink. Many labs rely on waste contractors trained to handle ionic liquids safely. Mixing streams in the waste bin only leads to unexpected reactions. Always separate organic and inorganic wastes. Training sessions aren’t just a formality—those walkthroughs of near-misses and actual accidents stick with people longer than any online quiz.

Why Precautions Matter

Following the rules sounds tedious until a mistake happens. I once had a splash land dangerously close to an eye while swapping a flask too quickly. That moment raised my standards for lab safety. In research settings, people trust that yesterday’s carelessness doesn't put today's coworkers in harm’s way. Respect for the hazards means nobody brings a bottle out of storage unless fully alert, with gear zipped, and waste buckets ready.

Good science relies on sharp thinking and well-worn gloves. It’s not only about getting the reaction yield—it’s about making sure everyone walks out of the lab in the same shape as when they came in.

The Substance in Question

1-Allyl-3-methylimidazolium tosylate has appeared on the radar for researchers and those working with green solvents. This chemical belongs to the family of ionic liquids, a set of salts that stay liquid below 100°C. These compounds often draw attention because they tend to be non-volatile and display interesting chemical behavior. If you spend time reading scientific forums or academic journals, you’ll notice a debate around the water-solubility of this compound. Practical folks — chemists, chemical engineers, even environmental scientists — push for clarity since solubility shapes how a substance finds use in extraction, catalysis, and eco-friendly chemistry.

Personal Perspective on Solubility

I’ve watched young researchers get tripped up, guessing solubility based on similar compounds or on logic that doesn’t quite follow the real rules. In my own lab days, expecting a clear answer from a supplier often brought more confusion than help. For 1-allyl-3-methylimidazolium tosylate, the answer really matters. Knowing whether you can dissolve this compound in water determines workflow – it saves time, preserves materials, and keeps students from running down dead-end procedures.

What the Literature Shows

Peer-reviewed papers point to reasonable water solubility for this ionic liquid. Imidazolium-based ionic liquids commonly interact well with water. The structure — the imidazolium ring with an allyl group and a bulky tosylate anion — still leaves space for hydrogen bonding between the cation and water molecules. Experimental work from respected chemistry journals points to fast dissolution in aqueous systems at room temperature, even with moderate stirring. One paper in the Journal of Physical Chemistry B measured significant solubility — enough that researchers used it for extractions and electrochemistry.

Why Solubility Matters for Science and Industry

For the graduate student preparing a separation or a chemical engineer aiming for greener manufacturing, water solubility means more than theory. It means lower costs, fewer hazardous solvents, and the chance to design safer, cleaner chemical processes. Ionic liquids open new doors: the right one could replace conventional solvents in pharmaceutical extractions or help process materials that used to require loads of harmful chemicals. Think about water’s role — cheap, available, and safe — and it’s no wonder researchers insist on selecting materials demonstrably soluble in water.

Weighing Pros, Cons, and Solutions

Not every application benefits from this solubility. If your process demands a water-immiscible phase, another ionic liquid might fit the bill. But most green chemistry routes today target water compatibility. On the downside, water solubility can complicate recycling. Once in an aqueous phase, separation grows laborious unless you use energy-intensive distillation or clever membrane tech. Labs considering this chemical should weigh these challenges, and teams in industry tend to build in water treatment and recovery — not as an afterthought but as a design feature.

Looking to the Future

The evidence holds up: 1-allyl-3-methylimidazolium tosylate dissolves in water, suggesting real usefulness for anyone exploring solvents that do better for health and the environment. If more scientists and engineers ask tough questions about solubility early, fewer resources get wasted, and the field keeps moving toward concrete, sustainable innovation. There’s value in direct answers, strong data, and a willingness to re-examine what gets accepted wisdom in the lab.