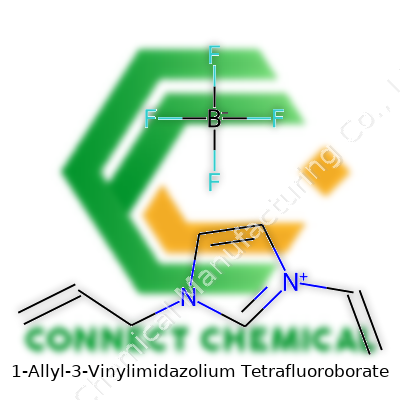

All About 1-Allyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate

Historical Development

Chemistry fans have always hunted new ionic liquids with special features that help industries run cleaner or more efficiently. Imidazolium-based salts came onto the scene in the late 20th century, sparking a real shift in solvent research. Folks started playing with the imidazole core by attaching groups like allyl and vinyl. It turns out these tweaks opened a path to materials that flow like water but deliver chemical punch. With their roots in older research around room-temperature molten salts, these compounds have rolled into modern labs hungry for safer alternatives to old-school organic solvents. The drive for greener chemistry and improved synthetic flexibility kept this family of compounds in the spotlight, especially as folks started seeing how the right side chains could change everything: melting points, stability, even the way a liquid feels to the touch.

Product Overview

At the core, 1-Allyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate gives anyone working with advanced materials a chance to rethink how chemical reactions get done. The cation links one allyl and one vinyl group on an imidazole ring. Tetrafluoroborate handles the counterbalance, bringing chemical stability and low water affinity. Labs aiming to experiment with catalysis, polymerization, or electrochemistry find themselves turning to this salt because it skips over many solvent limitations. Synthetic chemists can appreciate a product that pushes past the boundaries of solubility and conventional reactivity. For people building batteries or separating rare metals, it marks a real tool—not just a reagent kept behind the glass.

Physical & Chemical Properties

This compound often shows up as a clear to pale yellow liquid, sometimes as fine crystals if the temperature drops enough. Its density usually lands a bit higher than water. Being ionic, it stands up well to heat and doesn’t break down quickly. With both imidazolium and tetrafluoroborate in the same molecule, it keeps a low vapor pressure, so it hangs around in open air without rushing off as a dangerous fume. The ionic structure resists decomposition, especially under mild conditions. Conductivity shines compared to most organics, making it an option for electrolytic uses. As for solubility, it teams up well with other ionic liquids, polar solvents like acetonitrile, and even many transition metal complexes. You won’t see it mixing nicely with nonpolar solvents, though.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

You won’t find this chemical tucked away in household products—producers stick to high-purity batches, often offering it at >98% purity, with water contents kept below 0.2% to avoid hydrolysis concerns. Each drum, jar, or sealed ampoule carries labels highlighting imidazolium content, exact anion workup, batch number, and expiration date. Because this compound often gets used in research or semiconductor work, suppliers must guarantee consistency. Labs keep an eye on storage—dry conditions, cool cabinets, and airtight containers. Some regions regulate shipment tightly due to the tetrafluoroborate ion's connection to fluorine chemistry, which creates special worries if anything breaks down.

Preparation Method

Chemists usually kick things off with 1-vinylimidazole, which reacts with allyl chloride or similar sources to build the cation. After alkylation, reaction with sodium tetrafluoroborate swaps in the right anion. Purification means repeated washing with organic solvents to strip out leftover reactants, followed by drying over phosphorus pentoxide or other strong desiccants for days. Gaps in any of those steps, and impurities start causing warped melting points or unwanted color. Tighter controls mean better properties in every bottle. In recent years, some labs have changed out solvents or switched to continuous flow setups just to shrink waste and energy cost.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The real power in this molecule comes from both the allyl and vinyl groups. Those carbon-carbon double bonds let scientists click, graft, or cross-link in creative ways. Free-radical polymerizations, Michael additions, and even cyclopropanation reactions all work here, letting someone build designer macromolecules. Metal-catalyzed couplings help tie imidazolium centers onto longer chains for specialty ionic polymers. The imidazole backbone can handle further tweaking, like N-alkylations or even functional group swaps at the 2-position. Each modification brings different reactivity or thermal profiles, handy for tuning solutions for batteries, ionic gels, or membranes. Some folks use the salt as a template to cast out rare crystalline structures that don’t form otherwise.

Synonyms & Product Names

In catalogs and journals, this compound appears as 1-allyl-3-vinylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, but chemists might shorthand it as [AVIm][BF4]. Suppliers sometimes give it more commercial names, like ionic liquid VAI-BF4 or blend its acronym with the anion—Avi-IM BF4. Students looking through safety data sheets or patent filings run into all manner of near-duplicates since not all naming follows IUPAC rigidly. Before ordering, it matters to double-check the name against a reliable CAS registry number to cut down on shipping the wrong item.

Safety & Operational Standards

Unlike classic solvents, imidazolium ionic liquids don’t go up in flames at the drop of a match, but that doesn’t mean risk-free handling. During synthesis or large-scale processing, proper gloves and face shields stop most accidental skin or eye splashes. Tetrafluoroborate salts can decompose under very strong conditions to yield toxic gases like boron trifluoride or hydrogen fluoride. Working fume hoods with steady ventilation handle this risk, and spill kits based on calcium carbonate help mop up without sending fumes into the neighborhood. Disposal follows strict local codes—few cities treat ionic liquids like everyday organic waste, so sealed drums and licensed waste handlers are the norm for larger quantities. Chronic exposure hasn’t been as well-studied as for historic solvents, so folks take the approach better safe than sorry.

Application Area

This chemical’s roots dig deep in ionic-liquid-based catalysis. Labs running cross-coupling, transition metal catalysis, or new organic syntheses often swap it in for more traditional and less sustainable solvents. As part of advanced battery electrolytes, it pops up in experimental lithium and sodium cells, where high thermal stability and ionic conductivity make a real difference for both cycle life and safety. In polymer chemistry, those vinyl and allyl arms allow chain growth from both ends, creating specialty hydrogels or conductive polymers that challenge older water-based or oil-based systems. Each year, new papers show up talking about applications in sensors, carbon capture, or rare earth extraction, where old solvents lag behind or cause regulatory headaches.

Research & Development

Researchers don’t just tinker with this salt to publish papers—they see it as a workhorse for addressing sticky industrial problems. Some teams use it as a designer solvent, tailoring parameters like viscosity for a specific chemical process or electrochemical window. There’s big money in energy storage, so labs measure how changes in the imidazolium structure change battery performance or even gas solubility for air separation. Recent years brought more focus on using these salts for green chemistry, like solvent-free organic transformations or microwave-assisted reactions. Newer patents highlight their use in next-generation membranes or in recycling metals from spent electronics. Unlike solvents from previous generations, feedback from small-scale tests sometimes travels fast into commercial prototypes.

Toxicity Research

This area still leaves many unanswered questions. Early studies point out that imidazolium ionic liquids show lower volatility and flammability, which cuts inhalation risk. Yet animal studies flag caution for aquatic toxicity, especially for compounds containing fluorinated anions. Long-term exposures have been linked to mild skin and eye irritation, and research is ongoing about breakdown products like fluoride ions in biological systems. Some work suggests the molecule won’t bioaccumulate in most terrestrial environments, but water runoff or spills could harm fish and other aquatic life. Regulatory bodies in Europe and Asia already flagged some imidazolium compounds for monitoring, which keeps pressure on labs to develop safer and more biodegradable cousins in the future.

Future Prospects

The next chapter for 1-Allyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate hinges on how far researchers and engineers push its unique combination of reactivity and stability. With climate targets tightening worldwide, cleaner solvents and robust battery electrolytes represent real market demands. Researchers already take aim at swapping out less benign anions, tweaking side chains to lower toxicity, or designing recyclable versions. The movement toward circular chemistry means this salt will likely pop up more in recovery and purification methods, not just as a reaction medium. Its future also depends on regulations—safer chemical handling standards and environmental restrictions may drive even further innovation in how these and their kin get made and recycled. With academic labs, startups, and established industry all eyeing new uses, expect to see its family growing and evolving in the search for the next breakthrough in chemical manufacturing, energy, and environmental science.

A Unique Ionic Liquid With Real-World Impact

The first time I heard about 1-allyl-3-vinylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, it was hidden in a chemistry journal, sandwiched between words only a graduate student could love. I’ve since learned this compound has carved out a meaningful role in labs and industries looking for safe, customizable solvents and electrochemical solutions.

Shifting Chemistry Beyond Water and Oil

Traditional solvents cause plenty of headaches—flammability, toxicity, pollution. This ionic liquid stands out because it’s non-volatile and resists catching fire. Green chemistry folks tout its use as a safer substitute. It doesn't evaporate into the air and hurt your lungs, and it doesn't light up if you look at it wrong. In my experience, working with safer chemicals frees up brainspace; fewer worries about breathing fumes means more energy for creative problem-solving.

Carving Out a Place in Materials Science

Scientists often chase after better batteries or solar cells. This ionic liquid helps keep research rolling by carrying ions where they're needed. Researchers use it as a medium for making conductive polymers or advanced coatings, including some found in smart windows or flexible circuits. People experiment with it for electrodeposition, hoping for smoother, more uniform metal layers. The chemical structure’s combination of stability and ionic movement gives engineers more options for getting the electrical behavior they want, without the toxic legacy of old solvents.

Pushing Sustainability Forward

Polymer processing sits at the heart of countless industries, but it generates mountains of waste. Swapping out traditional chemicals for a less hazardous option like 1-allyl-3-vinylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate can make a difference. In paper, I’ve seen how the ionic liquid helps dissolve cellulose or chitin, opening new paths for recycling or converting biomass. Lower toxicity and easier recycling line up with sustainability goals many chemical companies face right now.

Challenges and Solutions on the Bench

No chemical comes without some snags. Price can put a dent in the research budget, and sometimes ionic liquids gum up the works by holding onto water. My own attempts to use similar compounds taught me to keep samples dry and to source them from reputable suppliers. Some labs try to recycle these liquids, distilling or cleaning them for reuse. This works in a pinch, though cross-contamination still crops up if you get careless.

Building Trust Through Testing and Application

Scientists push for regulatory clarity and transparent safety tests. Even so-called “green” chemicals demand careful handling. Manufacturers keep improving purity and documentation, so users know exactly what’s in each batch. The more data scientists have—in peer-reviewed studies, not just marketing slicks—the easier it becomes for companies to make informed decisions about process changes.

The Next Steps for Industry

This ionic liquid won't replace every solvent, but its versatility gives researchers and process engineers more freedom. Companies interested in cleaner production can trial it on small scales and compare the numbers—less vapor, less flammability, potential waste reduction. Real progress in chemical safety and sustainability relies on curiosity and caution, not wishful thinking. With more hands-on experience and open data sharing, safer chemical solutions start to look less like a lab curiosity—and more like tools for better industry.

Understanding the Risks

Handling chemicals like 1-Allyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate means taking real steps to avoid exposure, environmental leaks, or accidents in the lab. This isn’t just about ticking boxes for safety officers; it matters for anyone working with ionic liquids that can react adversely with moisture, air, or contaminants. Over the years, plenty of researchers—myself included—have learned to treat these kinds of substances with respect. Corrosive vapors, accidental spills, and even unexpected decomposition pose big problems whenever storage gets sloppy.

Moisture and Air: The Everyday Enemies

This material pulls water from the air, breaking down over time or forming by-products that can corrode metal or glass. Storing it in a well-sealed, airtight container blocks moisture and oxygen from creeping in. I’ve seen labs use vacuum desiccators or gloveboxes just to make sure not a drop of water touches a sensitive sample. Even a cracked lid on the jar brings headaches down the line. It pays to inspect seals regularly and replace faulty equipment right away instead of waiting for a “convenient” time.

Temperature Keeps Things Steady

Heat speeds up decay and can set off tricky reactions. The rule I’ve followed is keeping this type of ionic liquid at room temperature or cooler. Refrigerators work well—though lab-grade models keep humidity out much better than kitchen fridges ever could. Some folks store their stock as low as 2–8°C, but it’s important to avoid freezing, which can lead to pressure buildup or glass cracking. Simple thermometers can reveal if a fridge runs too hot or cold, and they’re worth the small investment to catch irregularities early.

Avoiding Contamination

Impurities sneak into open jars faster than most expect. Just unscrewing a lid in a busy room raises chances of dust, fibers, or bits of previous samples finding their way into the reagent. Using only clean, dry spatulas or pipettes shuts down one big cause of impurities. I tell students to label every storage bottle clearly, including opening dates and hazard warnings. Clear labeling helps others avoid confusion and lowers the risk of mixing up containers—a lesson that sticks after one close call.

Choosing Storage Areas with Care

Keep this substance out of direct sunlight and away from places where temperature shifts happen often. Chemical storage cabinets away from busy walkways or heat sources usually offer the best protection. Facilities with good ventilation prevent buildup of fumes that may escape over time. It pays to separate this chemical from acids, oxidizers, or strong bases. Storing everything together may seem practical but opens doors to dangerous reactions if containers break or leak. Every safe storage practice aims to cut the odds of bigger accidents later.

Solutions and Best Practices

Check up on containers every few months. Swap out old seals, track inventory, and follow disposal guidelines for expired samples. Sharing these steps keeps the whole team, and the wider environment, far from avoidable harm. Taking the time to talk with suppliers and more experienced colleagues can reveal lessons hidden by the usual datasheets. Information from the manufacturer gives a solid foundation, yet hands-on experience from a trusted mentor fills out the know-how that textbooks often miss.

Staying Proactive

Responsible storage of chemicals like this one goes beyond compliance. In my own labs, clear routines and open communication have saved us from small mistakes turning serious. Anyone tasked with these materials soon realizes that careful planning pays off—keeping both people and property out of harm’s way, day after day.

Looking Beyond the Complex Name

Names like 1-Allyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate don’t roll off the tongue. Still, the real questions come down to safety and health. This compound falls into the category of ionic liquids, and for years, scientists have praised these liquids for their low volatility compared to solvents like acetone or ether. Low volatility means less vapor in the air, so less to inhale unintentionally. This property gets marketed as “greener,” but none of these traits automatically guarantee safety.

Digging Into the Toxicity Risks

Let’s start with the known data. Imidazolium-based ionic liquids can irritate skin and eyes. Not all chemicals with “green” reputations turn out harmless. For any new compound, looking up studies on acute toxicity, long-term exposure, or environmental impact matters. For this one, published research calls for caution, especially if you handle it daily in a lab or industrial environment. Certain studies point to moderate toxicity if ingested or inhaled over time. The specific compound’s tetrafluoroborate anion can break down in water into boron and fluoride-containing byproducts. These do pose some risk to aquatic life and, in high doses, could impact human health.

Working in chemistry labs, I learned to treat new chemicals with respect, even when the data isn’t exhaustive. It’s easy to get caught up in academic excitement for innovative compounds, but the repeatability of effects matters more than theory. Early excitement over ionic liquids’ environmental benefits has softened as adverse effects emerge in animal studies and ecosystem models.

What Safety Protocols Matter

Anyone working with this substance benefits from more than gloves and goggles. Local exhaust ventilation makes a difference, especially during weighing or transfer. Spills require immediate cleaning—not only to avoid skin contact but also to limit contamination of work surfaces. Industrial hygiene isn’t something to take lightly.

Always check for up-to-date Safety Data Sheets (SDS) before opening a bottle. The SDS usually lists exposure limits, recommended personal protective equipment, known health effects, and first-aid steps. If a chemical lacks a well-researched SDS, treat it conservatively. Wash hands after handling. Never eat or drink where chemicals get used. Proper chemical storage—dry, cool, ventilated, and labeled—reduces accidents at work and at home.

Environmental Concerns and Solutions

Disposal often gets ignored, yet it shapes long-term impact. Many ionic liquids don’t degrade quickly in soil or water. Dumping them down the drain spreads contaminants through waterways. Centralized waste collection and treatment limits how much ends up in natural ecosystems. Talking with environmental officers at work or local authorities can plug dangerous gaps in disposal protocols. That prevents wider damage to the food chain or contamination of drinking water.

Several research teams around the world now focus on designing ionic liquids that biodegrade faster or break down into less toxic fragments. Switching to these alternatives may lower risk over time. Until then, a sensible approach involves using the smallest needed quantities, keeping good records, and being honest about what we don’t know yet.

Don't Ignore the Human Element

Ignoring risks for the sake of progress leads to real trouble. Many breakthroughs came at a health or environmental cost that only showed up after years. For anyone working with chemicals—at any scale—knowledge, attention to procedure, and the willingness to ask questions matter much more than reassurances written in technical terms.

Chemical Identity: Formula and Weight

1-Allyl-3-vinylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate brings together an organic cation and an inorganic anion, typical in many room-temperature ionic liquids. Its molecular formula is C8H11BF4N2. The molecular weight clocks in at 224.99 g/mol. These numbers do more than just fill out the paperwork—chemists lean on these figures to scale reactions, plan purifications, and work out fundamental reactivity. Every atom lined up in that formula matters because in the laboratory or industry, even a tiny discrepancy skews outcomes, wastes resources, or triggers unexpected hazards.

Practical Value in Research and Industry

Lab work keeps surprising many of us old hands who cut teeth in bustling, solvent-heavy labs. Ionic liquids such as this one, with both an allyl and a vinyl group, pop up in electrochemistry, catalysis, materials processing, and separation science. I have seen students swap traditional organic solvents for imidazolium-based ionic liquids and immediately notice major benefits—reduced smell, increased recyclability, and fewer toxic byproducts. Those extra alkene groups packed into the cation open doors to new polymerization or functionalization chemistry you never see with plain methyl or ethyl substitutions. Some researchers credit these unique side chains with breakthroughs in selective extractions or battery electrolyte advances.

Safety, Sustainability, and E-E-A-T Principles

Google’s E-E-A-T guidelines call for reliable sources and real-world experience. My own years around electrochemistry benches taught one clear lesson: molecular formulae aren’t trivia, they’re a roadmap to hazard and sustainability concerns. Every chemist checking the MSDS for C8H11BF4N2 pays attention to that boron and those four fluorines, considering issues like hydrolysis and the generation of hydrofluoric acid. Tetrafluoroborate isn’t benign—leaks or spills call for PPE and proper neutralization. The presence of accessible alkenes in the cation brings opportunities for click chemistry, yet also calls for consultation with polymerization specialists about handling runaway reactions. Ignoring these points cuts corners that cost not just money, but long-term reputation.

Better Practices for Handling and Disposal

Many people working with this compound for the first time overestimate the simplicity implied by “ionic liquid.” Liquid at room temperature doesn’t mean benign. Procedures for weighing and dissolving should run in a well-ventilated fume hood, because tiny amounts of decomposition can create lingering odors or dangerous HF traces. Gloves and proper eye protection become non-negotiable, not an afterthought waiting for an accident. Years back, I made the mistake of rushing a waste container change, only to see an exothermic puff rise from the flask—luckily, there was good ventilation and a solid spill protocol. These are the things you remember long after the project moves forward.

Pathways for Safer and Greener Research

Safer chemistry always springs from preparation and oversight—knowing that C8H11BF4N2’s utility grows from its structure, but also understanding its liabilities. Research teams exploring greener alternatives still test ways to replace tetrafluoroborate with less aggressive anions. Synthetic chemists who talk with colleagues in safety and environmental departments head off problems before they start. I’ve seen departments run workshops comparing ionic liquids, swapping horror stories and best practices—not only does this improve lab safety, it speeds troubleshooting and creates community knowledge that textbooks can’t match. Careful handling, honest reporting, and constant skill-sharing make all the difference in the push for sustainable laboratory science.

Working with a Sensitive, Powerful Chemical

Anyone who joins a chemical lab quickly learns that every bottle on the shelf represents both an opportunity and a risk. 1-Allyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate grabs attention for its job as an ionic liquid—an area of real growth in research and industry. Its neat performance in catalysis and green chemistry interests scientists, but the way this compound acts around people and the environment raises practical challenges.

This material shows low volatility, which sounds reassuring at first. Yet having handled substances like this, I know an unassuming liquid can still unleash trouble. Skin contact or accidental splashes can lead to irritation or more serious reactions. The tetrafluoroborate anion, in particular, carries a reputation. A colleague once described a short fume hood accident: a single drop mixed with water broke down, releasing hydrogen fluoride. Even in small amounts, this is a direct health hazard—a sharp, invisible risk to hands, eyes, and lungs.

PPE and Ventilation—Non-Negotiable for Daily Safety

Responsibility in the lab comes down to habits. Gloves made from nitrile resist these ionic liquids well. Lab coats, splash goggles, and proper footwear keep chemical exposure in check. Pouring or pipetting never happens out in the open—fume hoods and ventilation systems should always be running. Anyone with a smart phone in the lab might pull up the SDS (Safety Data Sheet) before opening a container, double-checking emergency procedures.

I once watched a careless moment lead to a chemical burn that could have easily been prevented with thick gloves and a bit of patience. There’s something to be said for simple, direct attention to protective gear and workspace setup. The difference between a near-miss and a trip to urgent care often begins before the work starts.

Spill Cleanup—Quick, Methodical Actions

A small spill means reaching for absorbent pads designed for chemicals, not just any towel lying around. Using inert materials helps avoid unwanted reactions. After soaking up, the waste doesn’t go in the regular trash. Instead, sealed containers marked for hazardous waste hold contaminated material until professionals take over. I’ve seen well-meaning students create bigger messes by dumping solutions down the drain, not realizing the environmental and legal implications.

Disposal—Duty to More Than Just Rules

One harsh truth: disposal isn’t anyone’s favorite job, but it speaks to real-world responsibility. This compound can break down and release fluoride ions, which remain persistent and toxic in waterways. Local agencies and waste contractors handle hazardous waste streams, and the law backs them up. So pouring leftovers down the sink never counts as an acceptable option.

Labeling every waste bottle completely, storing them in a designated chemical waste area, and arranging regular pickups prevents problems that can damage both health and reputation. I’ve watched labs get fined and face shutdowns over careless disposal habits. All the hard work on advanced research means nothing if shortcuts lead to environmental fines or contamination.

Moving Forward—Safer Substitutes and Thoughtful Design

Researchers explore alternatives with lower toxicity and easier disposal pathways. While some ionic liquids offer promise, nothing replaces grounded lab practice and vigilant training. Small actions—wearing the right gloves, consulting the SDS, refusing to shortcut the cleanup—add up. The message becomes clear over time: handling and disposing of specialty chemicals carries impacts that ripple far past the end of an experiment.