1-Aminoethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide: A Practical Commentary

Historical Development

Looking back at the story of 1-Aminoethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide, it's clear that the pursuit of greener, more efficient solvents started picking up real pace in the late twentieth century. Researchers turned to ionic liquids as the old solvents brought stubborn pollution and safety problems. This compound, known by chemists for its catchy abbreviation [AEIM][NTf2], showed up on the scene as folks searched for room-temperature liquids with low volatility and high thermal stability. Anyone following the evolution of ionic liquids will recognize its roots in the drive to replace volatile organics and handle emerging tasks like biomass processing, organic synthesis, and battery electrolytes.

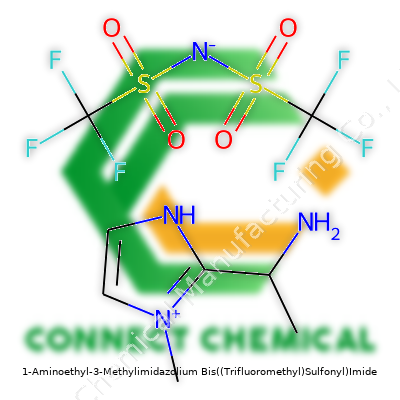

Product Overview

[AEIM][NTf2] falls in the family of functionalized imidazolium-based ionic liquids. Its imidazolium core, modified with a methyl and a 1-aminoethyl group, links up with the bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide anion. Compared to its simpler imidazolium cousins, the extra functional groups shape not just how it behaves, but how it fits into specialty applications. Chemical suppliers may sell it as a tailored ionic liquid, highlighting features like its nitrogen functionality or its moisture stability.

Physical & Chemical Properties

This ionic liquid stands out with its clear, slightly yellowish appearance and viscous texture at room temperature. Thanks to the NTf2 anion, [AEIM][NTf2] resists water quite well and offers a low melting point—remaining liquid through a broad temperature range. Its molecular structure prevents much evaporation, so it stays put in open systems, even under a gentle heat. Density sits right around 1.4–1.5 g/cm³, and the compound handles high voltages before breaking down, supporting its use in advanced battery chemistries. The aminoethyl group tunes its solvation power and can participate in hydrogen bonding, setting this liquid apart from less interactive ionic liquids.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Manufacturers release this liquid with strict moisture and halide content limits, often less than 50 ppm water and under 20 ppm halides, since traces of these affect conductivity and reactivity. Containers get marked with chemical name, batch number, net weight, and a hazard label warning about skin and eye contact. In storage, amber glass or PTFE bottles work best, away from sunlight and minor leaks, since the product tends to react with high-energy oxidizers and acids.

Preparation Method

The lab synthesis usually starts with 1-methylimidazole and (R)- or (S)-1-chloroethylamine hydrochloride. After stirring these under dry nitrogen with a controlled base, the intermediate salt forms and undergoes metathesis with lithium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide in water or an organic solvent. The resulting ionic liquid separates, washed with water to remove salts, dried with molecular sieves, and finally filtered for a transparent product. Yield often depends on keeping air and moisture out—otherwise side reactions spoil the batch. Each step needs careful control, especially during solvent removal at reduced pressure, since a shortcut here can leave residues and compromise downstream reliability.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The amino group on the cation lets [AEIM][NTf2] form covalent bonds or serve as a catalyst scaffold. In cross-coupling or esterification reactions, this moiety sometimes reacts with activated esters, isocyanates, or aldehydes, creating modified ionic liquids tailored for catalyst support or enhanced extraction. The NTf2 anion stays inert almost everywhere, but under intense electrochemical conditions, traces can decompose—proving this compound still has its limits despite strong stability. In practice, most chemists prefer [AEIM][NTf2] for its compatibility with transition metals and ease in recovering reaction products via extraction.

Synonyms & Product Names

Scientific literature and supplier catalogs list this liquid by its IUPAC name, 1-aminoethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide, or just [AEIM][NTf2]. Sometimes researchers call it by trade names or shorthand like aminoethyl-imidazolium NTf2. Some laboratory logs abbreviate it further, but formal reporting sticks to the full designation for clarity—especially since the distinction between methyl- or ethyl-imidazolium makes a real difference.

Safety & Operational Standards

Conversations with lab techs who routinely handle [AEIM][NTf2] emphasize the importance of gloves, goggles, and well-ventilated hoods. This isn't the sort of chemical to treat lightly—splashes irritate eyes, and the skin stings soon after contact. Spills should get mopped up with absorbent wipes and sent for hazardous waste disposal. Fire codes call for keeping the compound away from open flames and hot plates not rated for chemical work, since its decomposition liberates harmful fumes, including hydrogen fluoride derivatives in extreme cases. Written lab procedures set safe temperature and pressure ranges, so accidents stay rare, but that happens only when people respect the material and don't take shortcuts during transfer or measurement.

Application Area

People first picked up [AEIM][NTf2] as a neat solvent for organic reactions, given its resistance to water and non-volatility. In my own experience, this liquid worked well in metal-catalyzed couplings—products came out without residue, and the ionic layer could be reused after washing. Today, research teams use it in electrolytes for advanced batteries, supercapacitors, and dye-sensitized solar cells. Its electrochemical window favors stable cycling and cuts side reactions, so you see it mentioned in patents for high-performance energy storage. In separation science, this ionic liquid dissolves tricky organics and helps pull rare metals from mining leachates, dropping the long-term environmental impact by swapping out nasty organophosphates.

Research & Development

The academic world highlights [AEIM][NTf2] for custom catalysis and green chemistry projects. Recent papers explore tweaks to the amino group for specific reactions or pairing this liquid with nanoparticles to make smart gels, membranes or sensors. Partnerships between universities and private labs ramped up as folks realized the wider potential in energy and environmental tech—less waste, more recycling, new approaches to old problems. The largest research gap still lies in scaling up production without losing purity or increasing cost, since the current process needs careful handling and expensive precursor chemicals.

Toxicity Research

Toxicological data for [AEIM][NTf2] keeps evolving. Animal studies show mild skin irritation and some effect on aquatic life, but acute toxicity rates stay lower than many organic solvents. Chronic exposure hasn't produced evidence of carcinogenicity, but the lack of long-term epidemiological data means routine surveillance stays important. Disposal in municipal water treatments stays off-limits, since ionic liquids tend to persist and disrupt microbial processes at higher concentrations. Labs that work with this compound now follow protocols set out by REACH and EPA guidelines, using designated collection and incineration partners for waste streams.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, [AEIM][NTf2] draws attention as new energy materials and green syntheses take center stage. Its adjustable structure offers a platform for synthesizing job-specific solvents or supporting recyclable catalysts, especially in CO2 reduction, hydrogen evolution, and biotransformation processes. Startups already eye this liquid for clean label batteries and efficient electrochemical devices, but growth depends on access to scalable, cost-effective synthesis and real evidence of benign environmental profiles at the end of use. The next era likely hinges on whole-lifecycle analysis, strict waste controls, and creative engineering that steers [AEIM][NTf2] from niche research to broader industrial adoption—stadium lighting, electric transit, or next-generation plastics made with these ionic liquids could move from paper to practice in the upcoming decade.

Changing Chemistry in the Lab

Much of what I remember from days working in academic labs centers around finding tools that solve tough separation problems. 1-Aminoethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide, or IL-1 for short, showed up in more than one set of experiments. Chemists like this ionic liquid because it works where water and oil don’t mix. You drop some IL-1 in and suddenly all sorts of stubborn compounds dissolve. This quality matters for extracting rare earth elements from old electronics, recycling materials from used batteries, and even cleaning up solvents in chemical production. I’ve watched teams recover expensive metals in ways that seemed impossible a decade ago.

Boosting Clean Energy

In batteries and capacitors, researchers look beyond just storing charge. These days, they focus hard on safety, long life, and higher energy. IL-1 enters the scene as an electrolyte. Unlike everyday salts, it won’t catch fire. That lets engineers put more punch into a battery without sweating over thermal runaway. I’ve seen test cells running at temperatures that cooked my old lithium-ion phone, but with IL-1 they just kept humming. This helps electric vehicles and grid storage, since longer life and better safety mean fewer worrying headlines about battery fires and more trust from people making the switch to renewable power.

Working with Gases

Factories need clever ways to scrub carbon dioxide and other gases from their exhaust. IL-1 comes up in talks about carbon capture. Because it pulls in CO2 from a stream without needing crazy high pressures or harsh chemicals, it saves energy. And after it grabs the carbon, you can often release it by just warming the liquid. This kind of system has the knack for handling nasty gas mixtures that would foul up normal filters. It’s not just theory: I’ve seen serious pilot projects testing IL-1 on smokestacks. The hope is cutting down on power plant pollution without blowing the economics out of the water.

Greener Chemistry

Nobody wants factories dumping toxic solvents into rivers. Over years in process chemistry, talk always came back to “greener” ways to make life-saving drugs or next-generation plastics. IL-1 delivers as a solvent that's not volatile, so it doesn’t send noxious fumes into the air. Chemists using it cut solvent waste and simplify recovery. That’s a plus for pharmaceutical manufacturing, where purity and safety come front and center. Instead of needing several potentially dangerous chemicals, a team can often use just IL-1, recycle it, and help keep workers and nearby communities safer.

Barriers and Next Steps

Price stands out. IL-1 costs more than industrial solvents like acetone or hexane. Production at scale still brings hurdles, both in chemistry and supply chain. Scientists need to knock down these costs and lower its environmental footprint from cradle to grave. Some companies are investing in new, cleaner ways to build these ionic liquids. Policy support might help, too. Right now, the push for safer, greener industry keeps demand steady, especially as regulations tighten. If researchers can prove reliability and lower costs, we may find IL-1 in applications well beyond the lab, stretching into everyday products, transportation, and clean industry.

What Happens to a Product Over Time

Every chemical product responds to the world around it. Even a sealed bottle on a warehouse shelf faces air, light, temperature swings, and moisture. Some compounds change only a little, but others can break down or even become dangerous. The nature of each product—whether it is an active ingredient in a medicine or a cleaning agent—shapes how long it remains safe and reliable.

Breakdown Can Cost More Than Money

More than wasted inventory sits behind poor stability. Medicines lose their intended power, sometimes transforming into byproducts that bring risks. In food, preservatives only do their job if they last to the table. Simple changes in color, smell, or texture often signal bigger chemical changes underneath. Mistakes in storage conditions can lead to recalls, health scares, or legal action.

Heat, Light, and Air: Enemies of Stability

Heat acts as a catalyst, speeding up reactions that might take years at room temperature. Even one hot summer in a poorly ventilated stockroom can shorten shelf life. Many vitamin and pharmaceutical products lose strength when exposed to heat. Light breaks down certain compounds fast. Anyone who has seen the yellowing of aspirin tablets or fading ink knows this effect firsthand. Air causes oxidation—a process that rusts metal but can also spoil foods, ruin oils, and destabilize chemicals.

Moisture and Packaging—The Silent Factors

High humidity invites trouble. Water can kick-start chemical reactions or nourish microbes that wouldn’t grow on dry powder. Some products soak up moisture so quickly they turn clumpy, sticky, or even start releasing fumes. Packaging plays a huge role here. A tightly sealed container, made of glass or a sturdy polymer, blocks out more trouble than a flimsy bag or lid that cracks.

Stubborn Realities in Storage Practices

Even the best instructions fail if ignored. Some suppliers count on distribution channels or end users to store items under “recommended conditions,” yet many skip climate control or leave products under bright warehouse lights. This isn’t just laziness—small clinics and shops may lack fancy storage spaces. Labels matter, but so does direct training for people handling the products. I have seen firsthand how well-meaning staff store sensitive test kits near radiators or sunsplashed windows, not realizing the impact.

Moving Toward Better Stability

Manufacturers improve stability not only with formulas but also through practical solutions. Desiccants absorb leftover water. UV-blocking containers offer low-cost upgrades. Advances in materials science—like vapor-barrier foils or oxygen-absorbing packets—buy months or years of extra safety. Simple monitoring tools, such as temperature strips or humidity cards, warn users when conditions slip out of range.

Real-World Solutions Start With Awareness

Understanding why storage rules exist helps people actually follow them. It isn’t enough to print “Store below 25°C” or “Keep tightly closed.” Training must show what goes wrong without these safeguards. Companies can study failure rates and track patterns. The pharmacy world uses batch tracking and expiry checks. Real transparency, with detailed stability data, lets customers make informed choices.

Responsibility Runs Through the Whole Chain

From factory floor to final user, the story of chemical stability comes down to vigilance and respect for science. Whether protecting children from faded medicine or preserving food in harsh climates, choosing better storage keeps products honest. As regulations grow stricter and consumers demand trust, open sharing of stability data and smarter packaging become basic standards, not extras.

Looking Past the Label

A lot of folks spot a chemical name on a drum and shrug, “Is this stuff safe?” The answer doesn’t come easy. Some names blend right in, others send a chill down the spine. I’ve spent enough time around labs and shop floors to know that every compound needs a second look, even the ones that seem harmless. Take sodium hydroxide, for instance. It hides in cleaning products under different names, but it can cause burns with a single splash. Just recognizing the name isn’t enough. Reading the safety data sheet and understanding the risks sets the bar for real workplace safety.

Shortcuts Can Spell Trouble

People cut corners, sometimes thinking a little exposure won’t hurt. Stories from industry prove otherwise. Over the years, health agencies have documented what happens when proper handling gets skipped. Benzene became known for its link to leukemia. Even after regulations dropped exposure limits, accidents still happened because someone mishandled a drum or skipped gloves, trusting their gut instead of the guidelines. I’ve seen folks spend months recuperating from what looked like a simple mistake—just forgetting goggles while pouring a solvent.

Labels Only Go So Far

Regulators require hazard pictograms, and those help. Still, hazard ratings can confuse even seasoned crew members. Flammable means one thing to a fire marshal and something else to someone sorting trash. It takes training, not just labels, to bridge that gap. Employers forget that handling procedures make the difference between an average workday and a serious incident. Chemicals like sulfuric acid don’t just sit on a shelf. They react with flesh, metal, even the air. Overreliance on labels breeds complacency, and that’s a real enemy in a lab or on the plant floor.

Solutions Built on Teamwork and Training

What keeps people safe? Regular drills and open conversations. New hires often admit they skipped hazard training in past jobs. Leaders need to invest in sessions that go beyond slides—real-world scenarios, live demonstrations, and Q&A with folks who’ve seen incidents firsthand. Good practice sticks when everyone understands the “why” behind it. Take something like naphtha. It’s part of countless products, but even veteran workers can forget how fast it can ignite. Practical training saves lives, much more than reading warnings off a poster.

Staying Ahead with Learning and Leadership

Safety culture doesn’t grow out of reminders or rules alone. It takes a mindset willing to watch for trouble and speak up before something feels off. Chemical handling isn’t just about PPE or checksheets. It matters how everyone responds in those split seconds after a spill or unexpected reaction. Over the last decade, company records and government reports point out the same lesson: listening, learning, and leading by example set apart the firms with solid safety from those written up after an accident makes the news.

If you ever find yourself asking if a compound is hazardous, trust your gut and check the facts. Don’t just wait for someone else to weigh in. Every bit of caution adds up to a safer workday for everyone.

Down-to-Earth Properties: What Melting Point Means in Labs

Ionic liquids break the old rules of chemistry classrooms. Unlike classic salts like sodium chloride, which need an oven-hot reach before they melt, many ionic liquids go soft below 100°C. I remember the first time I held a small vial of an ionic liquid—room temperature, no crystals, not even a whiff of the salt-cube crunch. It didn’t feel like any “salt” I’d ever handled in a high school chemistry lab.

The trick comes down to the ions themselves. Bulky, asymmetric structures (picture messy, mismatched puzzle pieces) keep the ions from packing closely together. This loose fit means less energy required to pull them apart, so melting points often dip down to the warmth of your palm. Some well-known versions like 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate routinely handle temperatures found in a warm office, not a roaring furnace.

Melting temperature matters much more practically than most text resources admit. If you’re running a reaction, that accessible melting point means you don’t need elaborate setups to keep things liquid. No need to clamp flasks above a Bunsen burner for hours, hoping not to overshoot. It keeps energy bills lower and working environments safer. The same physical property pushes ionic liquids into delicate jobs—coating sensitive electronics, managing heat in batteries, or serving as tough, non-volatile solvents in labs where water or organic solvents pose big headaches.

Solubility: Why it Affects Everything

Solubility tells us whether an ionic liquid becomes a helpful partner or a sticky mess. In my own projects, I’ve seen how a liquid’s friendship with water decides success and failure. Some ionic liquids cozy up to water and dissolve at impressive rates—they handle polar compounds and allow you to wash out products more easily. Others want nothing to do with water, staying separate like oil and vinegar, and they keep organic reactions neat, without water poking its nose in and spoiling things.

The reason for this difference comes back to the ions. Alkyl chain length, charge distribution, and anything that interrupts hydrogen bonding with water will steer the whole behavior. Longer non-polar tails, and you get less water loving. Shorter chains or more polar groups, and water jumps right in. In practice, this means chemists often have to check tables and real-life results—not accept theory as gospel. I’ve lost count of times an unexpected solubility outcome forced me to change an extraction setup or tweak a reaction plan on the fly.

Supporting Data and Thinking About Solutions

Some ionic liquids take solid at room temperature, while others melt well below that. For example, 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride boasts a melting point around 77°C; a different cousin, 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, sits liquid well below 0°C. Their practical roles jump out of published data: a paper in Chemical Reviews highlights room-temperature ionic liquids being used as solvents for green chemistry—not just because they’re liquid, but because their solubility handles stubborn organic or metal-containing solutes easily.

The environmental friendliness of ionic liquids takes hits if they dissolve too easily in water and end up in streams, with toxic cations or anions causing havoc. One real-world fix includes creating “task-specific” ionic liquids, tweaking both the cation and anion so the solvent performs its job but stays put where it should. Research out of the University of Alabama shows progress by adding functional groups to reduce water solubility or increase biodegradability, limiting environmental fallout while keeping unique lab benefits.

Why These Properties Hit Home

Ionic liquids offer benefits that go beyond simple textbook characteristics. Melting point and solubility play front and center, not as technical trivia, but as concrete factors shaping safety, product design, and environmental concerns. My own hands-on time with them keeps reminding me that the right physical properties—matched to the job—mean chemical progress without as many compromises.

Digging Deeper into What Makes a Product Useful

Anyone who’s spent time in a lab knows organic synthesis boils down to smart decisions about what actually works, not just what’s possible. Picking a catalyst or a solvent is sometimes a gamble, and sometimes a matter of experience. There’s always a stack of new compounds and materials hitting the market, and the question circles back: Can this particular product step up as a catalyst or a solvent? I’ve fumbled through this decision-making more than once, and sometimes a novel material will surprise you, but other times the basic chemistry draws a clear line.

How Catalysts and Solvents Stack Up

The world of organic chemistry relies on a few simple needs: speed, selectivity, and outcomes. Catalysts are all about making reactions go faster or opening up different routes that weren’t accessible otherwise. They should boost the yield, not get consumed, and ideally, let you skip extra cleanup steps. Solvents dissolve reactants, control temperature, and sometimes sneak into the reaction itself as a participant.

Now, not every promising compound is going to tick all those boxes. A catalyst has to latch onto something specific. Certain transition metals, acids, or organocatalysts have given rise to entire industries because of what they can do in a reaction flask. The late nights I’ve spent trying to wrestle a stubborn reaction into working usually involved swapping out one catalyst for another – and nothing’s more frustrating than a product that deactivates after one use, leaches into the final product, or brings unwanted byproducts along for the ride.

What to Look For: Real-World Needs

It isn’t enough to have a cool structure or a hot new publication. A catalyst or solvent has to make sense in the real world. That means stability, availability, safety, and, more than ever, environmental impact. The shift toward greener synthesis makes the choice even sharper. My time working on small-molecule drugs showed how a solvent that works like a charm in the lab can blow up budgets or environmental risk in the plant – nitromethane, for example, brought headaches for waste management teams.

A product with low toxicity, easy removal, and a friendly environmental profile stands out, especially with regulatory agencies tightening their grip. Ethanol and water now show up in places where exotic, petroleum-derived solvents once reigned. Even in catalyst selection, folks avoid heavy metals and lean toward biocatalysts where possible, despite some bumps in performance.

Testing, Not Just Reading

Company brochures and clever marketing might promise the moon, but actual hands-on work proves what sticks. Patents mention new ligands and solvent combinations, but lab work quickly reveals solubility limits, pH quirks, or temperature sensitivity no paper mentions.

One easy test: drop the material in a real reaction. Watch for clean conversions, product isolation, and practical workups. Nobody wants to run a reaction that makes waste handling a nightmare. Early engagement with suppliers, running small-scale screens, and sharing ugly results as well as clean ones go further than shiny data sheets ever could.

Solutions: Communication and Ecosystem Thinking

If a product shows promise, the best route involves direct interaction between synthetic chemists, engineers, and suppliers. Upfront honesty about reactivity, hazards, and compatibility with current methods helps push good materials into broader use. Open forums, published case studies, and real process feedback speed up the cycle from bench to production.

At the end of the day, the chemistry matters, reputation follows results, and new products must weather scrutiny from all sides. Years of trial runs remind me that seeing is believing, especially with catalysts and solvents. Only careful testing, honest reporting, and attention to both yield and safety will tell if a product belongs in a synthetic chemist’s toolbox or the scrap heap.