1-Butyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Thiocyanate: A Deep Dive

Historical Development

Big changes in chemical engineering started showing up in the late 1990s, and that's when ionic liquids caught a lot of attention for their low volatility, high thermal stability, and unique solvent properties. Among these, 1-butyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium thiocyanate—sometimes called [BMIM][SCN]—grew out of the need for versatile ionic liquids that could replace volatile organic solvents in everything from catalysis to material science. By the early 2000s, chemists had already shifted focus from simple imidazolium salts to those with more complex alkyl substitutions, chasing greater tunability for specific tasks. The combination of the butyl and dimethyl branches on the imidazolium ring together with a flexible thiocyanate anion opened up fresh possibilities for non-aqueous and non-volatile electrolyte systems. Labs in Europe and East Asia got busy tweaking these molecules, and by 2010, their work had driven a small avalanche of patent applications around alternative electrolytes and solvent systems—putting this compound firmly on the radar of universities and specialty chemical companies alike.

Product Overview

1-Butyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium thiocyanate stands out as an ionic liquid, liquid at room temperature, that brings an oddly slippery, slightly oily consistency. Most suppliers, including well-known laboratory chemical companies, sell it by the gram, highlighting its utility in electrochemical studies, polymer processing, and as a medium for chemical transformations. This compound’s popularity isn’t just because it’s a novel solvent; it ties back to the growing industrial and academic push toward ‘greener’ chemistry, since it doesn’t evaporate like old-school volatile solvents and can often be recycled within a process. I’ve handled related imidazolium salts in a university lab, and you quickly notice that, compared to acetonitrile or dichloromethane, there’s next to no smell and far less skin or eye irritation—making it easier to breathe, work, and clean up.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Looking at its makeup, 1-butyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium thiocyanate appears as a colorless to pale yellow liquid, staying fluid at temperatures well below those that send water running for cover. Its melting point rarely creeps above -10 °C, and it boils at temperatures high enough to outlast most organic solvents. The density floats around 1.0–1.1 g/cm3, and its high viscosity means it pours slowly from a bottle, kind of like light syrup. Thanks to its imidazolium backbone, this salt refuses to combust in ordinary lab settings, and resists thermal breakdown up to at least 180–200 °C. The thiocyanate anion is polarizable, adding a twist to the liquid’s solvent properties—dissolving both polar and some non-polar compounds, boosting extraction yields where plain water or traditional solvents fall short.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Most suppliers ship this compound in amber glass bottles, labeled for research use with a purity often above 98%. Typical certificates of analysis include spectroscopic data (NMR, IR), water content (sometimes below 0.5%), and trace metal analysis, since the presence of copper or iron throws off sensitive catalytic experiments. Labels list the CAS number, proper chemical name, and hazard warnings—mainly about skin or eye irritation and the risks that go with improper storage. Some providers also test for thermal decomposition onset and ionic conductivity, details essential for anyone building batteries or electrochemical sensors.

Preparation Method

Synthesis starts with the alkylation of 2,3-dimethylimidazole—producing the butyl derivative—with a halobutane under mild basic conditions. Once the 1-butyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium halide is ready, anion exchange with a soluble thiocyanate salt (often potassium or sodium thiocyanate) in water or acetonitrile does the trick. After separation from inorganic byproducts, washing, and drying under reduced pressure, the ionic liquid comes out as a clear liquid or slightly yellow, depending on how clean the process runs. The final product sometimes takes an extra pass through activated charcoal or alumina to drag out left-behind halides or colored impurities, since those affect both appearance and electrochemical stability.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

1-Butyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium thiocyanate shows remarkable stability against strong acids and most weak bases, making it a favorite choice for solvent engineers looking to run redox or coupling reactions. The methyl substitutions on the imidazolium ring change the electron distribution, making this particular ionic liquid less likely to break down during aggressive reactions than its plain butyl cousins. In organic synthesis, this salt helps out as a solvent in nucleophilic substitutions, C-C couplings, and even in biocatalysis, where traditional organic solvents quickly deactivate enzymes. Chemists curious about tuning its properties sometimes swap the thiocyanate for other anions—or modify the alkyl branches on the ring—tweaking viscosity, polarity, and solubility each time. Such modifications lead to a family of related liquids, each with its own sweet spot in chemical or electrochemical applications.

Synonyms & Product Names

The chemical goes by several names: 1-butyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium thiocyanate, [Bm2im][SCN], or simply BMIM-SCN in shorthand. Most catalogues include all the alternatives alongside CAS identifiers, so researchers don’t accidentally order the wrong product. Some companies trademark niche versions, tweaking the process and tagging them as “ultrapure” or “battery grade,” mostly targeting specialty markets in electronics or analytical chemistry.

Safety & Operational Standards

Lab safety with this ionic liquid looks straightforward compared to the dangerous reputation that haunts many commonly used organic solvents. The low volatility nearly wipes out inhalation risk, making spills far less dramatic. The main hazards relate to direct contact—eye splashes or skin exposure can cause mild to moderate irritation, especially during long experiments. I always keep nitrile gloves on when pouring or cleaning up spills, not least because repeated exposure to imidazolium derivatives sometimes leads to sensitization. Proper storage in a cool, dry place avoids water uptake, which otherwise dilutes the salt and shifts its physical properties. Disposal stays within typical organic solvent waste protocols, even though it produces fewer emissions.

Application Area

Electrochemistry labs use 1-butyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium thiocyanate to build electrolytes that stand up to voltage swings and heat. Battery researchers lean on its low flammability and electrochemical window when testing next-generation electrodes, especially in lithium or sodium-based systems. It finds a home in separating rare metals, dissolving cellulose for greener plastic processing, and running organic reactions that just fizzle in regular media. Materials scientists employ it to process polymers and nanomaterials sensitive to water or standard solvents. Even analytical labs experiment with its potential in liquid–liquid extraction and chromatography. The variety comes down to the solvent’s high polarity and ability to dissolve both salts and organic compounds, giving researchers new levers in reaction control and material design.

Research & Development

Research around this compound dives into both practical uses and the fundamentals of ionic liquid chemistry. Academic groups fine-tune its role in catalysis, enzyme stabilization, and metal recovery. In the last decade, efforts expanded into green chemistry, where people look to minimize waste and energy, and 1-butyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium thiocyanate checks a lot of boxes. Battery and supercapacitor engineers pump resources into understanding how its ions move at surfaces and how to squeeze more stability out of the electrolyte at high voltages. Collaboration between chemists, physicists, and engineers continues to push this field, and new publications pop up every year documenting improvements in synthesis purity, application efficiency, and recycling strategies patterned off closed-loop industrial systems.

Toxicity Research

Most toxicity studies show that this ionic liquid, much like its close relatives, only causes mild irritation at practical concentrations, but concerns linger about chronic exposure and environmental breakdown. Animal studies suggest low acute toxicity, but incomplete degradation in soil and water raises questions about ecological persistence. Some published findings note that excessive exposure can inhibit aquatic microorganisms, and persistent ionic liquids build up in waterways if not properly managed. Labs and factories working with these salts continue to invest in closed systems and improved containment, minimizing accidental release and keeping public health risk nearly zero.

Future Prospects

Demand for stable, low-volatility solvents won’t slow down anytime soon. With tightening regulations on industrial air quality and a push to drop unsustainable chemicals, 1-butyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium thiocyanate finds itself in a prime position. New battery technologies, plastics processing, and even pharmaceutical syntheses need liquids that can endure tough conditions without choking up plants or harming workers. Research keeps unlocking new modifications that improve biocompatibility and recovery after use, helping push these salts into new fields. If more work goes into solving the environmental persistence problem—breaking them down reliably at end-of-life—they could transform ‘green chemistry’ from a buzzword to a real industrial standard, broadening the reach of ionic liquids from boutique labs all the way to global manufacturing.

The Role of Modern Ionic Liquids

Chemistry has seen a shift in recent decades, and part of that progress comes from ionic liquids. One that has caught the eye in research circles is 1-Butyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Thiocyanate. This mouthful represents a compound prized for what it brings to the lab bench and industry. I remember first encountering it in a university lab, and talk quickly turned to its unique mix of stability and low volatility.

Why Scientists Turn to These Compounds

Water and common organic solvents often set limits in chemical reactions. Some solvents evaporate fast or risk catching fire, causing headaches in labs. But with certain ionic liquids—like this one—you get something different. They hardly evaporate and don’t burn with the same ease as traditional solvents. I found this especially helpful during a project on enzyme catalysis, where keeping the temperature down and air quality up cut back on distractions and let me focus on the work.

Application in Chemical Engineering and Synthesis

1-Butyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Thiocyanate serves as a solvent or medium for tough-to-dissolve materials. Researchers know how stubborn cellulose can be, especially from plant fibers. With this ionic liquid, breaking down or modifying cellulose gets less complicated. Some labs harness its qualities to prepare biofuels or turn plant waste into useful chemical feedstocks. The process skips nasty byproducts and slashes the use of harsh chemicals, speaking to a shift toward greener practices.

Bringing Sustainability into Focus

Consider the challenge of cleaning up after chemical reactions. Traditional solvents can create more chemical waste than the product you want. Ionic liquids like this one often get reused. During one research placement, we filtered and recycled our ionic liquid at least three times without seeing a dip in performance. That takes a weight off anyone watching their waste streams and carbon footprints, especially as regulations tighten and public concern grows about pollution from labs and factories.

Influence in Electrochemistry and Advanced Materials

This compound hooks into projects on batteries and supercapacitors, where reliable solvents affect stability and energy storage efficiency. Ionic liquids help manage ions, guide reactions, and stabilize new materials for next-gen energy storage. Teams across the globe test out these liquids for selective electrodeposition or as electrolytes in advanced batteries. Anything that pushes batteries to last longer, work safer, and charge faster proves vital as electric cars and renewable energy depend on better storage solutions.

What Stands in the Way

Ionic liquids—including 1-Butyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Thiocyanate—carry a price tag that can break a lab’s budget if used in bulk. Production methods still leave room to improve in cost and reducing environmental harm. Researchers and industry insiders aim for greener synthesis and easier recovery, hoping to spread the benefits without passing big costs down the line. As more labs publish real-world data and safety details, demand for improved production should nudge the market to respond.

Paths for the Future

Deciding which chemicals fill the world’s labs and factories always boils down to more than performance. The push for sustainability, better economics, and safety brackets every decision. As I see it, 1-Butyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Thiocyanate points the way for next-gen chemicals balancing all three. The more we learn and share about its strengths and limits, the more likely we make headway in safer science and better technology.

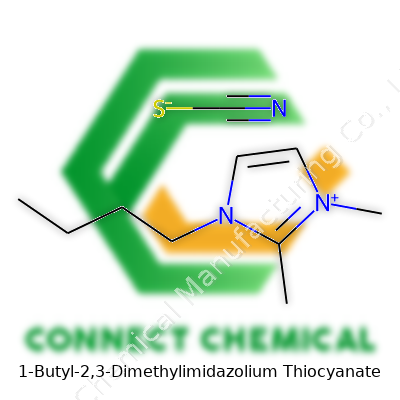

The Formula and Its Significance

1-Butyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium thiocyanate packs a punchy chemical formula: C9H17N3S. Drawing from work in chemical research labs, formulas like this one capture so much more than numbers and letters; they map out how elements build new materials. In this instance, the cation comes from an imidazolium ring, tweaked with butyl and methyl side chains. The anion rounds things out — thiocyanate brings the S and the extra N. Together, they form an ionic liquid, which means it stays liquid below 100°C. You find immense value in these liquids for research, green chemistry, and manufacturing settings.

Why This Compound Draws Attention

I’ve seen chemists reach for 1-butyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium thiocyanate because it opens doors to dissolving stubborn substances. Ionic liquids often replace volatile organic solvents, making labs safer and less polluting. A clear formula, like C9H17N3S, guides safe preparation and proper handling—a slip in calculation can throw off a reaction or, worse, endanger a team. It’s not just about memorizing symbols; it’s about knowing what those symbols can do or undo.

Lately, there’s been a push to move away from traditional organic solvents, which release tons of harmful VOCs (volatile organic compounds) each year. Ionic liquids offer a practical and sometimes non-toxic option for industry. In my own experiments, swapping out a solvent for an ionic liquid often simplifies the clean-up process, cuts down on chemical waste, and delivers a much more stable environment for reactions. Even allergies caused by solvent fumes dropped noticeably for some colleagues.

Supporting Data and Responsible Use

Looking at the science, a 2018 paper from the Journal of Molecular Liquids showed ionic liquids like this one can boost efficiency in biomass conversion. That means more biofuel, less waste, and a sustainable route out of fossil fuel reliance. Numbers show one kilogram of ionic liquid can process more cellulose compared to traditional methods, which gives a strong case for wider use. Still, no chemical is perfect. While this compound doesn’t evaporate easily, disposal creates questions — lingering thiocyanate in soil or water may pose risks if ignored.

Safety matters. Sharing a busy lab in grad school, I watched a spill response drill turn into a lesson in protocol. Solid chemical formulas support the right labeling and storage, and everyone feels better about what’s on their shelf.

Digging for Better Solutions

There’s never a one-size-fits-all answer in chemical management. Regular reviews of how ionic liquids like C9H17N3S perform—and what impact their use leaves—keep chemists honest. Training and easy access to safety information cut down on accidents. Cleaner disposal methods rooted in the latest research keep waterways healthy and neighbors happy. Open-hearted communication between researchers and regulators helps build trust and ensures that the next round of scientific breakthroughs stands on solid ground.

Understanding the Substance

1-Butyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium thiocyanate belongs to a broad class called ionic liquids. These chemicals often catch attention from green chemists seeking alternatives to traditional industrial solvents. The reason is simple. Ionic liquids don’t evaporate quickly, so they cut down on air pollution from chemical processes. Many people, though, assume this property means they are automatically safe. That isn’t accurate.

What the Data Says

Toxicity for most ionic liquids sticks out as a major research topic. Data for every possible compound? Not always easy to find. Looking at 1-butyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium thiocyanate, studies in peer-reviewed journals and safety data sheets offer a mixed picture. The imidazolium ring often appears in cytotoxicity tests because scientists worry about effects on human cells and aquatic life. Some members of this chemical family cause cell damage at relatively low doses. Others disrupt aquatic organisms even when diluted. The thiocyanate part adds its own concerns as thiocyanate salts sometimes interfere with thyroid function in mammals and fish, especially at high exposure levels.

There’s no getting away from the simple idea: the absence of volatility does not make a substance non-toxic. The chemical’s structure, dose, and route of exposure all matter. Reports have linked similar ionic liquids to skin and eye irritation and flagged them as potentially hazardous to aquatic ecosystems. Even limited inhalation, ingestion, or skin contact with some imidazolium compounds knocked lab rodents off balance, affecting body weight and organ health.

Lab Experiences and Personal Perspective

I’ve handled a few ionic liquids myself in chemistry labs. Safety goggles, gloves, proper ventilation—I never let those slide. Colleagues with stories of spills on exposed skin or splashed eyes usually end up running straight for the safety shower. That isn’t just protocol, it’s necessity. Not every symptom shows up right away. Slow onset issues—itching, rashes, or headaches—can sneak up hours later. Disposing of waste requires care too. Never down the drain. Ionic liquids can slip past wastewater treatment and raise a red flag for aquatic life.

Workers and students sometimes trust the “green solvent” buzzword, so they get careless. But my experience taught me to treat any unfamiliar substance with caution and double-check each new chemical on safety databases like ECHA or the NIOSH registry. In industry, I’ve seen companies quietly switch out old solvents for ionic liquids to comply with air quality rules, but the switch brings new training and waste controls.

Looking Ahead

If this compound sticks around in academic labs, production plants, or research facilities, clear risk assessments belong front and center. Manufacturers ought to make real toxicity data publicly available, not tucked away in technical libraries. Workers and students benefit most from easy-to-read Safety Data Sheets that don’t duck the tough questions: Will it burn? Does it corrode skin? Should it go to hazardous waste?

Better engineering controls like fume hoods, splash guards, and glove compatibility tests help prevent harm. No single solution will erase risk entirely, but transparent labeling, honest training, and prompt spill response make a real difference. Ionic liquids often enter the spotlight as the green path forward in chemistry, but responsibility means looking past the hype and reading every line of the safety sheet before the bottle even opens.

A Chemical Worth Respect

1-Butyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Thiocyanate sounds like science fiction, but it’s a reality for many labs working with modern ionic liquids. Over a few decades in chemistry labs, I’ve watched more than one promising project ruined by casual attitudes toward chemical storage. Handling this compound with care goes beyond reading a safety sheet; hazards often pop up in the most routine moments—busy mornings, crowded shelves, or a moment’s distraction.

Heat, Sun, and Air Are the Enemy

Every chemist eventually learns there’s no shortcut around temperature control. If this material sits near a window or lives next to a hotplate, surprising reactions can follow. I remember the mess a co-worker faced after a similar ionic liquid degraded thanks to a warm shelf. Most ionic liquids want to be cool, dry, and shaded. I always check my thermometer—below 25°C, preferably even lower—since heat can nudge some chemicals toward degradation or volatility. The chemical doesn’t love moisture, either. Labs get humid on rainy days or when air conditioning stutters, and humidity slips into even closed containers. Dampness can trigger slow changes in some synthesized compounds, leading to clumps, weird odors, or even sudden color changes.

Sealing and Labeling: Not Just Bureaucracy

In my experience, even the world’s best chemist can’t remember every bottle’s story, especially after a few hectic weeks. I slap on a tough, legible label with the full compound name and storage date. Double-checking lids for tight closures and using containers with built-in gasket seals keeps out air and spills. Skipping this step once led to a confusing contamination episode during my early post-grad days, and I’ve never forgotten it.

Chemical Neighbors Matter

Storage placement means something. Putting this ionic liquid next to strong acids or oxidizing chemicals can produce headaches or contamination. Keeping highly reactive chemicals apart avoids surprise reactions, especially during cleaning or stockroom reorganizations. I use a chemical-resistant tray or secondary container as insurance—if a bottle cracks, the mess stays contained. This habit came from one dramatic cleanup after a glass flask burst beside a mismatched chemical, nearly shutting down the facility for a day.

Why It Matters Beyond the Lab

Accidents in a lab affect more than experimental results. Volunteers, students, and new hires deserve a safe environment, not just working chemists. Five years ago, I witnessed a shelf collapse, sending unlabeled bottles across the floor. Improper storage and carelessness with seals became lessons in how fast small errors snowball. This isn’t just a matter of keeping research running; health and safety ripple out to the whole community.

Every Storage Step Counts

Recognizing the risks of heat, light, humidity, and neighboring chemicals forms part of a practical approach to safe storage. Check containers, label them well, and keep them separated. Even with experience, I don’t rely on routine—every bottle gets a second look. Protecting people in the lab, the environment, and future research starts with good habits made routine.

Getting to Know This Uncommon Ionic Liquid

People working in chemistry love a shortcut. If something dissolves in water, they’ll say it’s “water-loving.” The compound in question, 1-Butyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Thiocyanate, falls under a category called “ionic liquids.” These are salts that can stay liquid at room temperature. That’s not something you find every day. Their mix of properties, like low volatility and thermal stability, often puts them in the spotlight for green chemistry and next-gen materials research.

What Happens in Water?

Lab work has shown that this ionic liquid dissolves quite well in water. The butyl chain and two methyl groups make the molecule fairly flexible, so it gets along with the water molecules surprisingly well. This means you won’t see chunks or crystals hanging around after mixing—at least if you’re reasonably careful with concentration. In practical terms, you’re looking at solubility well above 1 molar under room temperature, which leaves a clear solution behind.

Mixing it with water doesn’t set off bubbles or a temperature spike the way some aggressive salt solutions do. The thiocyanate part is also more water-friendly than a lot of other anions, so it doesn’t fight hard against dissolving. That’s a big reason this compound pops up in research projects focusing on green solvents and advanced batteries.

What About Other Solvents?

Trying to get this ionic liquid to dissolve in non-polar solvents, like hexane, turns into an uphill battle. Sit this liquid in a vial of hexane and most remains separated for hours, if not longer. These kinds of ionic compounds don’t mingle well with oily, hydrocarbon-based liquids. Think of it like mixing salad oil and vinegar; no matter how hard you shake, they drift apart.

With organic solvents that sit somewhere in the middle, like acetonitrile or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), you’ll usually see moderate solubility. These solvents have just enough polarity, along with some hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, so they don’t push the ionic liquid out. Researchers interested in electrochemistry, catalysis, or separations often lean on DMSO or acetonitrile for this reason. It comes down to matching the “like dissolves like” principle many of us learn early on in chemistry class.

Why Care About This?

If you ever plan to use this ionic liquid in the lab, every hour you save on mixing, filtering, or purifying frees you up to tackle more interesting problems. Easy water solubility translates into simpler waste treatment and cleanup. This dovetails with green chemistry efforts to cut down on hazardous solvents and streamline processing. As someone who’s spent afternoons coaxing stubborn powders into solution, a compound that skips most of the headache stands out.

On the innovation front, labs aiming to reduce toxic waste look for handy alternatives to volatile organic solvents. Because this compound blends so smoothly with water, teams can design processes that sidestep health and safety headaches. You also sidestep expensive solvent recovery steps. More time for the experiments that actually matter.

Better Choices and Future Directions

Many problems still show up. Some applications might demand a solvent with less water present, in which case picking ionic liquids based on different cations or anions might solve solubility hitches. Others might focus on tweaking the length of the butyl group. Research journals keep turning up new variations with slightly adjusted properties, chasing better performance in extraction, catalysis, or electrochemical cells.

As labs run more real-world tests, the odds improve for finding new applications where this compound can shine beyond just being easy to dissolve. Clear data, down-to-earth process choices, and building on what works—these help new science move from a bottle on the shelf to real impact in technology, energy storage, and more.