In-Depth Look at 1-Butyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Acetate: History, Properties, and Future

Historical Development

Once chemists began focusing on ionic liquids as replacements for traditional organic solvents, a handful of discoveries changed the way researchers approached green chemistry and industrial solutions. 1-Butyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Acetate (often known as [BEIm][OAc] or BEIM Acetate) didn’t emerge overnight, but grew out of the surge in ionic liquid research during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Scientists needed a solvent that tackled the problem of volatility and flammability from older alternatives, steering toward substances made from ionic pairs. Imidazolium-based salts, for instance, delivered thermal stability and a remarkable chemical window, especially in fields where water or organics fall short—cellulose processing, catalysis, and biomass conversion. Decades of accumulated expertise allowed chemists to fine-tune substituents like the butyl and ethyl chains, balancing hydrophobicity, viscosity, and other key parameters. That journey continues to shape new approaches in biotechnology and engineering research.

Product Overview

1-Butyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Acetate steps onto the industrial scene with confidence, delivering a unique set of features. At room temperature, this ionic liquid behaves as a clear, colorless-to-pale yellow fluid. Unlike conventional solvents, it doesn’t evaporate or catch fire easily, earning a spot on many lab benches where safer alternatives are always in demand. Its low vapor pressure alone would make it useful, but it’s the ability to dissolve cellulose, lignin, some proteins, and other challenging biomaterials that unlocks its value for technologies far beyond its early days in academic research. Producers package it in sealed containers, measuring purity and moisture content with strict quality control.

Physical and Chemical Properties

A closer look at the properties paints a picture of versatility. BEIM Acetate carries a melting point usually around room temperature (10–25°C), and stays stable up to temperatures that push above 200°C. Its viscosity clocks in higher than water, and that thickness can actually help certain reactions by suspending solids or suspending catalysts. Being an ionic liquid, it conducts electricity moderately well, bridging the gap between the average salt solution and a true electrical insulator. Water happily mixes into BEIM Acetate, but an excess can affect performance for key applications, so people keep containers tightly closed. The pH sits close to neutral, though the acetate anion tips the balance toward slight basicity. These features don’t just represent technical specs—they guide daily choices for process engineers and research teams.

Technical Specifications and Labeling

Every bottle leaving the factory carries detailed batch information. Standard specs highlight chemical identity: 1-butyl-3-ethylimidazolium acetate, CAS number 400295-33-2, and molecular formula C11H20N2O2. Producers state assay (often above 98%), residual moisture (usually below 0.5%), and the impurity profile. For regulated industries or export markets, certificates of analysis from every batch provide assurance against contamination or adulteration. Labels also mark hazard codes, shelf life, and storage conditions—cool, dry places away from strong oxidants and acids get the nod. Familiarity with these standards helps buyers and users make decisions rooted in safety and reliability.

Preparation Method

Manufacturing BEIM Acetate doesn’t demand exotic equipment, but the chemistry requires careful control and deep technical knowledge. Typically, the route starts with 1-Butylimidazole, followed by alkylation using ethylating agents (like ethyl bromide or ethyl iodide), forming the 1-butyl-3-ethylimidazolium bromide or iodide. After purification, ion exchange introduces the acetate moiety, replacing the halide with an acetate donor (sodium or silver acetate). Purification steps involve a mix of filtration, solvent washes, and vacuum drying. Each stage brings potential for impurities, so process optimization and analytical monitoring matter a lot when meeting quality benchmarks for pharmaceutical, energy, or material science uses.

Chemical Reactions and Modifications

Chemists have put BEIM Acetate through its paces, probing its reactivity and versatility. Its biggest contribution often lies in dissolving stubborn biopolymers like cellulose—a job that makes it key for biomass conversion and biorefining. Besides extraction and dissolution, BEIM Acetate serves as a reaction medium for cross-coupling, transesterification, and enzymatic catalysis. Swapping the anion changes solubility, viscosity, and stability, giving rise to a suite of “task-specific” ionic liquids tailored for particular challenges. In catalytic cycles or synthesis, it lets reagents find each other without unwanted side reactions that sometimes plague water or volatile organics.

Synonyms and Product Names

Names can vary by supplier or publication. 1-Butyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Acetate pops up as BEIM Acetate, [BEIM][OAc], and less often as C11H20N2O2. Major chemical providers use house codes or catalog numbers when listing it for sale. Research papers sometimes shorten the name to BEMIM Acetate or list structural formulae, but the base identity stays rooted in the imidazolium acetate core. Familiarity with these aliases becomes important when searching suppliers, interpreting safety data, or reviewing scientific studies.

Safety and Operational Standards

Laboratories and industrial plants approach BEIM Acetate from a practical safety perspective. The fluid itself resists ignition under normal conditions and doesn’t produce toxic fumes like traditional chlorinated solvents. Even so, exposure risks can include skin and eye irritation, particularly during large-scale handling. Manufacturers align with standards like OSHA, GHS, and REACH, mandating gloves, goggles, lab coats, and strict waste-handling protocols. Ventilation and spill containment plans factor into safe operating procedures, especially since ionic liquids can sometimes pick up impurities or hydrolyze into problematic byproducts. Detailed Safety Data Sheets (SDS) help users anticipate hazards, storage needs, and first-aid responses.

Application Area

BEIM Acetate proves its worth across a wide range of modern industries. Foresters and paper technologists tap it for biomass pretreatment and biofuel production, thanks to a knack for dissolving lignocellulosic feedstocks. Synthetic chemists use it as a solvent or reaction medium for cross-coupling or polymerization. Electrochemists work with it as an electrolyte in batteries or capacitors that require high ionic conductivity and stability. In pharmaceuticals, the liquid finds a role in experimental drug delivery, protein isolation, and crystal engineering. Its blend of low volatility and thermal stability sparks interest in research labs and production lines where conventional solvents fall short.

Research and Development

Innovation around BEIM Acetate continues to build in momentum. Green chemistry goals drive the quest for more renewable sources to go into both the cation and the acetate anion. Researchers look for ways to recover and recycle spent ionic liquids, lowering cost and environmental impact. Analytical teams study catalytic cycles, exploring how BEIM Acetate changes rates, selectivity, or yields in new reactions. Material scientists blend the ionic liquid with polymers, nanoparticles, and enzymes, forging hybrid materials for sensors, coatings, or biomedicine. Each new patent or journal article deepens the bank of knowledge and opens the door to practical breakthroughs in both science and engineering.

Toxicity Research

Toxicologists have put BEIM Acetate under the microscope, evaluating possible threats to humans and ecosystems. Small-scale studies show low acute toxicity for skin and eyes, but chronic effects remain an active frontier. Researchers keep a close watch on environmental persistence and biodegradability, since ionic liquids can accumulate in soil or waterways if mishandled. Testing with aquatic species helps gauge risk, and ongoing monitoring shapes best-practices for disposal and clean-up. Most labs err on the side of caution, practicing containment and quick spill response, and investing in greener processing and recovery options.

Future Prospects

BEIM Acetate points to a future shaped by sustainable methods, expanding waste valorization, and safer manufacturing. Researchers chart new uses on the horizon, from next-generation biorefineries to recyclable energy storage devices, reflecting a broader shift away from fossil-derived solvents. Regulatory agencies strengthen oversight, pushing producers to refine methods for cradle-to-grave handling and lifecycle assessments. Collaboration between academia, industry, and government holds promise for scaling up applications beyond the lab, shaking up long-standing habits in chemicals, energy, and materials. Each step forward brings us closer to replacing outdated, hazardous technologies with smarter, safer alternatives.

What’s the Point of 1-Butyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Acetate?

Let’s call it “BEImAc” to save space and sanity. Science labs and factories look for liquids that solve tough problems every day. BEImAc ranks high on that list. It helps break down things that seem pretty stubborn—wood, straw, even old newspapers. When chemists want to take plant material and turn it into something new, like sugars or fuels, this liquid comes in handy.

Back in college days working in the “green chemistry” lab, we tried making biofuels from wood chips. Some solvents barely touched the stuff, but adding a proper ionic liquid like BEImAc turned the stubborn pulp into a workable soup. Even decades later, researchers agree: BEImAc dissolves cellulose—the stuff that makes plants tough—much faster than the usual chemicals. The science checks out, and you don’t see as much toxic waste in the aftermath.

Why Do Industries Bother?

If a company wants to cut waste or start making bio-based plastics, the process can get jammed by traditional solvents like lye or high-pressure steam. BEImAc fixes that by breaking plant fibers apart gently and quickly. Toss some farm leftovers into the tank with this liquid, and the rigid structures melt down. Suddenly, the path to ethanol fuel or biodegradable plastics doesn’t feel so far off.

A group at the U.S. Department of Energy ran a test with BEImAc and corn stover. They showed the sugar yield jumped way up compared to steam. That kind of improvement can save buckets of energy. Stack that with fewer toxic fumes in the air—you get both cleaner air in factories and easier cleanup.

Beyond the Biofuels Boom

BEImAc doesn’t stop at breaking down plants. Some researchers use it in batteries and advanced materials. Its mix of stability and ionic nature (there’s the chemistry nerd in me) means it helps in separating complex mixtures or even making better batteries. The solution works quietly in the background, but the end products—from cleaner plastics to lighter batteries—show why people keep coming back.

I’ve worked on projects recycling textiles, and it’s always disheartening to see usable fibers buried in landfills. With BEImAc, cotton and other natural fibers don’t end up as waste. Instead, they can be dissolved, sorted, even spun back into something useful. Real change comes when techno tricks like this leave the pilot stage and show up at the scale of whole factories.

Challenges and Ideas for Moving Ahead

No chemical comes for free. The expense of BEImAc still keeps it out of widespread use, and making large amounts of it calls for more affordable raw materials. Efforts to recycle BEImAc during production must succeed if it’s going to become more than a research lab favorite. Research teams have shown some promise reusing it, so this isn’t pure optimism. Cooperation between government and industry would help ramp up investment.

We need better systems to reclaim solvents at each step, both for cost savings and for protecting the environment. Transparency about the full production chain matters, too. Tossing in the word “green” doesn’t mean much if the manufacturing process leaves a hidden mess. People in the lab notice every cutoff valve and waste barrel; so should the companies behind bigger projects.

BEImAc opens doors for new products, jobs, and better handling of waste. It won’t solve every problem, but by backing up claims with repeatable results and open reporting, manufacturers and scientists can earn public trust—and change what ends up in the trash.

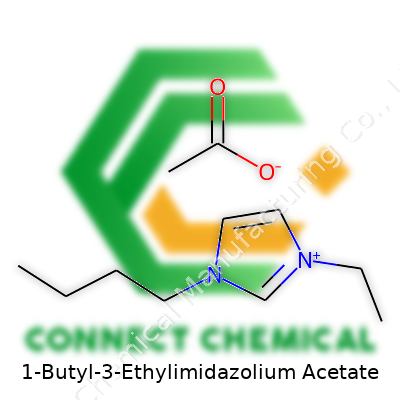

Breaking Down the Structure

Try to picture the backbone of an imidazole ring — a five-member planar ring with two nitrogens sitting quietly within the chain. Chemists love imidazolium salts because they act like room-temperature liquids, but also offer a lot of flexibility for researchers looking for new solvents. For this compound, one side of the ring holds a butyl group (C4H9), long enough to stretch away from the core, while the other side carries an ethyl group (C2H5). Both side chains attach to the nitrogen atoms of the imidazole, giving the molecule its signature: 1-butyl-3-ethylimidazolium.

The full name, 1-butyl-3-ethylimidazolium acetate, shows that this imidazolium core carries a positive charge, balancing it out with an acetate anion (CH3COO-). The chemical formula comes together as C11H20N2·C2H3O2. To draw it in your mind, link the long butyl and short ethyl to a five-atom ring with two nitrogens, then pair this positively charged species with an acetate ion—plain vinegar’s ionic sibling.

Importance in Modern Chemistry

Lab work often needs a solvent that doesn't evaporate too quickly, won’t burn at low temperatures, and stays stable even in weirdly strong acids or bases. 1-butyl-3-ethylimidazolium acetate offers all this. It comes into its own when you want to dissolve cellulose—think breaking down plant walls for making biofuels, spinning new types of fibers, or recycling clothing fabric. Traditional solvents run into big problems with safety or waste, but ionic liquids like this one let scientists skip some headaches.

Back during my grad school days, a team worked late into the night testing cellulose breakdown using classic solvents. Every time, the room would fill with strong smells and everyone would get antsy about the waste tanks filling up. When we shifted to specialty ionic liquids, especially ones like 1-butyl-3-ethylimidazolium acetate, labs cut down on harsh byproducts and smell. The sense of discovery shifts when you see stubborn cotton dissolve in a beaker of clear, almost odorless liquid.

Supporting Facts and Lab Realities

Ionic liquids have landed research grants for their ability to replace volatile compounds, which brings safety up a notch. Researchers published studies in journals like Green Chemistry showing that these salts dissolve up to 10% by weight cellulose at common lab temperatures. Real-world numbers back this up—researchers reduce energy consumption and deal with less hazardous waste. They help extract fine chemicals from plants, recycle valuable polymers, and even help pharmaceutical processes avoid awkward reactions linked to water or alcohol-based solvents.

Challenges and Practical Solutions

Cost and scale always pop up as sticking points. Synthesis remains expensive since the precursors are specialty chemicals and the lab techniques aren’t always friendly to big industrial reactors. Handling and recycling ionic liquids becomes a hot topic. My experience tells me that chemists should not just swap solvents blindly—ionic liquids carry their own toxicity profiles and need proper end-of-life plans.

Teams now work on better recycling methods, like vacuum distillation or membrane separations, to clean up and recover these valuable liquids after use. Green chemistry encourages design rules so every new ionic liquid is safer from the start—by studying biodegradability or toxicity alongside solubility profiles, researchers pick more responsible solvents.

Connecting Structure to Application

The success of 1-butyl-3-ethylimidazolium acetate rests in its structure: long enough hydrocarbon chains to coax stubborn molecules into solution, matched with an acetate counterion for balance. That tailored combination opens new doors in cellulose chemistry and spreads out into greener tech frontiers every year.

Why 1-Butyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Acetate Gets Attention

1-Butyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Acetate shows up often in chemical labs and green tech projects. Research teams value it for its role as an ionic liquid—people use it to break down biomass, tune reactions, or even clean up processes in factories. Curiosity about its properties is growing, but people shouldn’t overlook safety just because something gets tagged ‘green’ or ‘innovative.’

Looking at the Risks in Plain Terms

Early studies show that 1-Butyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Acetate raises less concern than harsh acids or common solvents like toluene, but it isn’t risk-free. On skin, it can cause irritation or redness. Direct contact with eyes may sting and redden, sometimes a lot. Swallowing any laboratory-grade chemical is a bad idea—this compound fits that rule. Research from journals like Green Chemistry points out that ionic liquids sometimes slip through the skin barrier or carry mild toxicity if inhaled as a fine mist. I’ve seen even experienced chemists get careless with new reagents just because the hazard label looked mild. That’s a mistake.

Everyday Mistakes and What They Teach

People sometimes ignore protective gloves for quick benchwork or lean forward for a closer look at a beaker. Even a splash on the sleeve can creep onto the wrist after a few minutes. A few years back, our lab trashed a shirt after someone used thin latex gloves instead of nitrile. The liquid seeped through, leaving a red welt. It cleared up in a few days, but nobody forgot that lesson.

Keeping Things Safer Step by Step

Risk stays low if folks respect the basics. Nitrile gloves stand up better than latex. Safety glasses cover more of the face than regular glasses. Working in a fume hood helps catch any nasty vapors or tiny spills, especially during transfers or pipetting. Even pipette tips can drip after use, so keeping wipes nearby avoids careless desk contamination. Clean up spills quickly using compatible absorbents, not bare hands or ordinary towels.

Training, Not Just Labels

Experience in the lab counts, but clear safety training makes a bigger difference. New people should get a quick walk-through on how to use and dispose of this compound. Labels or data sheets spell out risk in detail, but a five-minute demo showing how to don gloves, open bottles, or toss waste into the right bin prevents most trouble. It isn’t just about ticking off checklists—real accidents still happen even with great paperwork if basic habits slip.

Handling the Waste

Leftover ionic liquids go in special containers, never down the sink. Lab waste guidelines in most cities confirm this approach. Some facilities collect them for high-temperature incineration, the only proven way to break down these stubborn molecules.

Respect Overfear Wins the Day

Treating 1-Butyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Acetate with the same care as familiar lab solvents gets daily work done safely. No need for panic, just consistent respect and smart habits. People protect themselves best by sticking with the gear and routines that science, not rumors, has shown to work.

What’s in a Liquid Like This?

1-Butyl-3-ethylimidazolium acetate belongs to a family of ionic liquids that chemists have watched closely over the past two decades. You pour a bit out and right away, it's clear: This isn’t your everyday solvent. The stuff looks colorless, maybe straw-tinted. Touch the side of the glass vial, and there’s a heavy, viscous feeling that lingers. Unlike water, it doesn’t evaporate in an open dish, and its odor barely registers—a hint of something sharp, if you catch anything at all.

This chemical doesn’t want to catch fire. Its flash point sits high enough that lab workers rest a bit easier working with it than with volatile solvents. Water won’t scare it away, either. In fact, it draws moisture from the air, sometimes turning a little cloudy if given enough time unsealed.

Molecular Structure Tells a Story

The butyl and ethyl tails attached to the imidazolium ring create bulk, which holds the ions apart. In practical terms, this means the compound remains liquid across a broad temperature range, even when a cold snap hits the lab. Measuring its melting point puts it well below most organic salts, low enough to make it easy to handle without special equipment.

The bulk also changes how this liquid behaves around other molecules. Ask chemists who've mixed cellulose into it—they know this acetate-based version eats through plant walls, opening up tough fibers where more common solvents fail. This makes it stand out for deep delignification, the step in processing biomass that usually burns through time and money.

An Unusual Solvent with Some Surprises

Traditional solvents evaporate quickly, which can mean strong smells and handling risks. In contrast, 1-butyl-3-ethylimidazolium acetate stays put. That’s one reason it’s popped up in green chemistry discussions. Less air pollution, fewer hazardous emissions. Its high thermal stability also lets industrial teams run reactions hotter and longer if they need to extract more from a sample.

But every upside brings its own problems. Mix this ionic liquid with water, and it doesn’t always play nice. It’s hydrophilic, does not dissolve in nonpolar solvents, so cleaning the last traces out of equipment means plenty of rinsing. Plus, it can corrode certain metals over time. Anyone running large-scale processes needs to keep an eye on long-term maintenance and material choices.

Safety and Sustainability Questions

Handling the liquid poses less risk of flare-ups, so lab accidents tied to fire drop, but skin contact still matters. Prolonged exposure can irritate, so gloves come out in every lab I’ve worked in. Toxicity data remains somewhat patchy, with researchers noting the need for more studies on breakdown products and how they move in the environment.

While billed as part of the future "green" toolbox, this ionic liquid doesn’t break down easily in nature. Its persistence could build up, causing unknown effects. Focusing on better ways to recycle or recover it keeps popping up in journal articles and conference talks. Balancing its powerful solvent properties with environmental caution will shape how often it shows up in biorefineries and processing plants.

Building Better Solutions

Researchers continue tweaking the side chains and counterions to carve out improved versions with faster breakdown times, lower toxicity, and equal strength as solvents. Regulatory groups and funding agencies have learned from mishaps with other industrial chemicals, so they keep a close watch. In the meantime, everyone working with these newer ionic liquids shoulders a responsibility to log results, check waste streams, and not shy away from tough questions about the true cost of innovation in chemistry.

Why Thoughtful Storage Matters

1-Butyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Acetate doesn’t rank as the most dangerous chemical on the shelf, but ignoring basic precautions creates hassles no one wants. This ionic liquid, widely used in research for cellulose processing and other green chemistry goals, brings some unique quirks. My first time handling it was in a small university lab. The safety data sheet sat unread on a shelf, and folks treated it like regular salt solutions. After a minor spill, we learned the hard way—sticky, hard-to-clean messes don’t just vanish with a paper towel.

Hydroscopic and quick to soak up moisture from the air, this substance likes to pull water out of anything nearby, including your sample or experiment. I often keep it in a tightly sealed amber glass bottle, clearly labeled and stashed away from sunlight, heat, and open flasks of other chemicals. Heat breaks down this ionic liquid over time, or at least changes its properties, and light can spur slow degradation. Consistent room temperature storage, away from reactive acids and bases, keeps it reliable longer.

Labs won’t always have climate control or big fancy cabinets. A lockable, ventilated chemical cabinet set to room temperature works just fine. The trick is to keep the lid tight, never double-dip pipettes, and check all labels regularly. Taking notes like batch number, date received, and current volume helps if someone else handles the material later. Chemical allergies sometimes slip under the radar, so I wear gloves and a lab coat, even just for weighing a few grams. Goggles, too—no one needs a splash in the eye.

The Realities of Disposal: Smart Steps Keep People and the Planet Safer

The road to proper disposal gets bumpy fast. Local rules can shift from one institution to the next, but in my experience, nobody wants leftover 1-Butyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Acetate poured down the drain. It’s not just about pipes—it’s about keeping non-biodegradable chemicals out of water systems. Our team collects all waste in clearly labeled polyethylene containers—one for clean, uncontaminated material and another for anything mixed with solvents or acids.

Safer disposal relies on teamwork. Our lab works with a certified hazardous waste contractor who picks up containers once a month. The paperwork piles up—manifest forms, signatures, waste tracking logs—but skipping steps creates more risk for the worker shipping it and for the environment at the final treatment facility. Some universities run waste minimization programs. Instead of dumping the leftovers, we find ways to recover and reuse it, especially since the material isn’t cheap.

I’ve seen the mess left behind by shortcut takers. Improper disposal has led to minor chemical burns, environmental citations, even broken equipment. The EPA and OSHA guidelines help us avoid those mistakes. Never mix this material with strong oxidizers, acids, or anything reactive—it heats up, sometimes violently. Every time I consider ignoring the rules to save a few dollars, I remember the look on a colleague’s face after a broken beaker sent this ionic liquid sliding down a bench. Trust erodes fast if you cut corners with chemical safety.

Practical Solutions for Safer Practices

Personal responsibility and clear communication anchor safe practice. Label every bottle and waste container with the full chemical name and the date. Keep up-to-date inventory logs, and train everyone who handles the substance—even visiting students. If your facility doesn’t have a waste pickup option, contact local authorities for guidance or look for licensed disposal firms.

Small tweaks help: store only the quantity required, share leftovers with colleagues who can use them, and never stockpile for “just in case” projects. Chemical safety isn’t about fear or paperwork. It’s about respect—for your team, for yourself, and for the long-term health of the workplace and community.