Understanding 1-Butyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Bromide: Insights and Real-world Importance

History and Product Overview

Scientists began looking at ionic liquids like 1-butyl-3-ethylimidazolium bromide in the late twentieth century, searching for solvents that could shake off volatility, flammability, and the tight temperature ranges of traditional organic solvents. The history of this ionic liquid isn’t rooted in far-off pioneering, but in the practical, nuts-and-bolts work of chemists who saw the value in exploring alternatives that don’t boil off or catch fire at the sight of a bunsen burner. This compound brings together a butyl and an ethyl group on an imidazole ring—an architecture that looked simple on paper, but in practice, turned out to be temendously useful. Its arrival on the scene marked a shift in lab work and industry, offering a path away from solvents that make anybody with a sense of smell or caution reach for a fume hood.

Physical and Chemical Properties

1-Butyl-3-ethylimidazolium bromide stands out as a pale, sometimes colorless, crystalline solid at room temperature. It's heavier than water and doesn’t evaporate the way acetone or ethanol do. Instead of vanishing into thin air, it stays put, giving chemists more control and fewer headaches about environmental releases. Its melting point lies modestly above room temperature, meaning the solid-to-liquid transition comes with just a little warming in the palm. The high ionic strength gives the salt remarkable solubility for certain polar substances, making it a durable player in solvent systems. In water, it dissolves readily, breaking apart into ions that do the heavy lifting in extraction processes or catalysis. It doesn’t corrode metal as harshly as some halide salts, and its electrical conductivity opens doors for electrochemical work.

Technical Specifications and Labeling

Chemists usually source it in bottles labeled with the chemical formula C9H17BrN2, a molecular weight just over 231 grams per mole, and a warning about moisture sensitivity. The best suppliers mark their containers with purity ratings, usually 98% or higher, so labs can skip early purification steps. Clear labeling on incompatibilities, shelf-life, and recommended storage temperatures helps avoid ruined batches and wasted grant money. Quality matters, because even tiny traces of leftover solvents or unreacted starting material can wreck a high-precision synthesis, especially in pharmaceutical or materials science labs.

Preparation Method

The typical method for preparing 1-butyl-3-ethylimidazolium bromide starts with a simple exchange reaction, where 1-butylimidazole reacts with an ethyl halide (often ethyl bromide). The resulting quaternization rings familiar bells for anyone who’s spent time making alkylated imidazoles. Reaction times run several hours, and yields can climb past eighty percent with smart stoichiometry and careful drying of glassware. Solvents like acetonitrile help the process along, and the product crystallizes out after careful evaporation and purification. The steps might look textbook, but a steady hand and patient refluxing separate the rookie from the pro.

Chemical Reactions and Modifications

This ionic liquid handles functional group chemistry without fuss. Nucleophilic substitutions, oxidations, and reductions happen right in its bath, often with shorter reaction times and broader selectivity ranges compared to traditional solvents. It supports metal-catalyzed processes, letting researchers chase novel ligands and transition-state structures with a bit less worry about decomposition. Beyond acting as a solvent, chemists sometimes tweak its ring or swap the bromide for other anions, tuning solubility and reactivity to fit stubborn synthetic challenges. This kind of versatility is gold for anyone trying to scale up a process from the benchtop to pilot plant.

Synonyms and Product Names

1-Butyl-3-ethylimidazolium bromide might show up in papers or catalogs under names like BEIM Br, [BEIm][Br], or butyl-ethylimidazolium bromide. Translating synonyms and ensuring clarity across international borders underscores the importance of standardized nomenclature in chemistry. A mix-up here can mean failed experiments or dangerous byproducts, especially where purity or stoichiometry hangs in the balance.

Safety and Operational Standards

Normal handling of BEIM Br doesn’t trigger panic, but it tells a story about lab culture and respect for unknowns. Gloves and goggles aren’t optional; splashing the salt solution in your eye or on your skin raises trouble, since even ‘low toxicity’ ionic liquids penetrate the skin more easily than water. Some labs insist on air filters or closed bench work, limiting exposure to volatile byproducts in case other solvents come into play. Detailed MSDS sheets back up standard protocols, flagging the need to avoid strong bases and oxidizers that break down the imidazolium ring. Waste disposal often follows halide-salt guidelines, since bromides can spike environmental toxicity in the wrong hands.

Application Area

Industry and academia both see value in BEIM Br for extractions, catalysis, and electrochemical work. It acts as a phase-transfer catalyst, smooths out polymerizations, and supports battery research by serving as a safe, stable electrolyte. It’s found a spot in organic synthesis for stubborn substrates that fail to dissolve or react in common solvents. I’ve run reactions that fizzle in standard conditions, only to work like clockwork in this ionic liquid. Researchers use it in green chemistry, where low vapor pressure means less loss to the atmosphere and less risk to workers or neighbors. Process engineers look for these features when designing pilot plants with better safety margins.

Research and Development

Workshops and conferences see new tweaks to the basic BEIM Br structure almost yearly. Synthetic chemists have published scores of papers on swapping the butyl or ethyl for bulkier or more polar groups, each time chasing higher selectivity or new physical properties. Collaboration between universities and industry piles up case studies in catalysis, electrolysis, and CO2 capture. Researchers keep circling back to ionic liquids as replacements for volatile organics in both academic and industrial settings, searching for lower ecotoxicity, better performance, and greener processing. The technical literature keeps expanding as labs share notes on scaling crystallization, yield improvement, and handling quirks.

Toxicity Research

The push for safety has put BEIM Br under the microscope. It doesn’t show acute toxicity like classic bromides or aromatic solvents, but long-term studies have flagged slow environmental degradation and bioaccumulation in aquatic species. Some evidence links imidazolium-based ionic liquids to disruption in cell membranes for certain organisms. Regulatory agencies call for more research and better reporting on workplace exposure, especially with rising use in electrochemistry and green processing. Anyone working with these compounds should keep up with new toxicology studies and adjust protocols if the safety landscape changes.

Future Prospects

The chemists I know see ionic liquids not as one-trick ponies, but as platforms for continuous improvement. BEIM Br opens new directions for synthesis, energy storage, and separation because it bends instead of breaking under pressure from evolving tech needs. Combinatorial chemistry and machine learning may soon design customized analogs for precision tasks, building on the baseline performance of BEIM Br. Regulatory pressures will push researchers to prove its safety again and again, while sustainability targets in Europe and Asia drive demand for lower-impact synthesis routes. The road ahead for BEIM Br is paved with curiosity, collaboration, and the willingness to trade old solvents for better options, even if it means re-learning some of the basics.

The Science Behind the Name

Most folks never cross paths with something called 1-Butyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Bromide. For chemists, though, this compound means progress. It belongs to a class called ionic liquids, which are unique because they stay liquid at room temperature. That comes with some real advantages—no strong evaporative fumes, high thermal stability, and a serious ability to dissolve or mix with a ton of different substances.

Real-World Jobs—Far From the Textbooks

Think of industrial chemistry. Many traditional solvents bring headaches: environmental hazards, explosive risks, and chronic health issues for workers. Here’s where compounds like 1-Butyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Bromide step in. They replace older solvents in a variety of chemical processes. I remember a colleague who worked on cleaner ways to treat biomass; swapping to ionic liquids made it possible for their lab to crack open tough plant materials and get to the useful sugars inside, all without using toxic or flammable stuff.

Pharmaceutical labs now grab for these ionic liquids. They create more controlled environments for sensitive reactions. That stability helps labs produce cleaner drug ingredients, which is critical for safety and purity. Chemical engineers writing in Green Chemistry often point out that these exclusive liquids increase yields and lower the formation of nasty by-products.

Better for the Planet (and the People Doing the Work)

Traditional solvents like toluene or dichloromethane pollute air and water, leading to ongoing soil problems and breathing risks for nearby communities. Ionic liquids like 1-Butyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Bromide stick around instead of evaporating. That reduces workplace exposure. Plus, companies targeting greener certification standards get closer to their goals by using these tools.

Research from the Journal of Hazardous Materials breaks it down: once plant processing facilities moved to ionic liquid systems, chemical waste in wastewater tanks dropped by 35%. Waste management costs eased up, and workers felt safer.

Still Room to Do Better

Not all that glitters is sustainable. While ionic liquids outclass old solvents on many fronts, they don’t disappear from the environment on their own. If facilities don’t invest in recovery or recycling systems, the build-up can pose fresh risks. Some ionic liquids, including relatives of 1-Butyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Bromide, linger in soil and water. Science reviews warn that regulators and manufacturers need better data on long-term impacts.

Where Solutions Take Root

I’ve seen creative workarounds take shape. Companies with closed-loop systems capture and reuse these liquids in continuous cycles. Cutting-edge filtration sorts out contaminants, letting the solvent go back into the next production batch almost as fresh as new. Universities and startups keep pushing for new ionic liquids that break down faster or use renewable ingredients, making tomorrow’s chemistry even safer.

1-Butyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Bromide doesn’t just represent change—it shows how smart chemistry can transform risky processes into safer, cleaner routines. By keeping an eye on the whole life cycle and how the chemical fits into larger environmental systems, the industry can stay on the path to truly sustainable innovation.

Breaking Down the Name

Seeing a name like 1-butyl-3-ethylimidazolium bromide can seem more about chemistry class and less about everyday use. Still, getting to know these building blocks opens up new perspectives on how “designer” chemicals shape energy, manufacturing, and even the food we eat. Naming conventions give clues about how a compound fits together, with each part telling its story.

The Nuts and Bolts of the Molecule

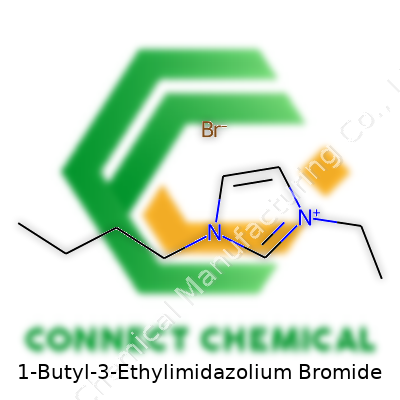

Think of it as a puzzle. The heart of this compound is imidazole, a five-sided ring made up of three carbon atoms and two nitrogen atoms, sitting at positions 1 and 3. Chemical creativity comes in with the substitutions: there’s a butyl group attached to one nitrogen and an ethyl group fastened to the other. These modifications turn imidazole into a positively charged imidazolium cation.

Swapping a hydrogen atom from each nitrogen with bulkier carbon chains not only changes how the molecule looks but also how it behaves. The butyl group—four carbons in a row—gives flexibility and adds to the so-called “grease” factor. The shorter ethyl group at position three acts as a counterbalance, tuning the molecule’s physical traits. Together, this forms the 1-butyl-3-ethylimidazolium cation. Bromide tags along to balance the positive charge, keeping things neutral.

Why Details Matter in Real Life

Not every chemical deserves a headline. But this one stands out as part of a wider family called ionic liquids. Unlike water or oil, these don’t evaporate at normal temperatures and usually have low flammability, plenty of chemical stability, and a knack for dissolving all sorts of stuff. I’ve spent time in labs trying to dissolve stubborn organic compounds, and ionic liquids like this bromide make the job easier. They don’t smell, they don’t burn, and they carry other molecules like a professional chauffeur.

It’s easy to assume something this “custom” probably lives only in a research paper, but the truth is that the chemical industry always looks for safer, greener alternatives. Out in the world, these molecules get used for tasks as specific as extracting metals from electronic waste or acting as catalysts that help reactions go faster and create less pollution. Some research shows ionic liquids with this structure can help batteries last longer, improving how we store renewable energy.

Safe Use and Future Directions

One thing that sticks out from my work is that not every innovation turns out rosy. A molecule that’s safe in one job could still cause harm if not managed the right way. Studies on imidazolium ionic liquids, including this one, track toxicity, biodegradability, and risks to water sources. Any new substitute for traditional solvents should come with detailed safety checks before moving past the lab bench.

Transparency from manufacturers, strong government guidelines, and ongoing research help keep misuse in check. Talking with chemists over coffee, it’s clear that seeing both opportunities and risks leads to smarter advances, not just faster ones. Sharing what works (or doesn’t) can keep the next generation of solvents as assets rather than accidents waiting to happen.

Building Chemistry on Trust and Science

1-Butyl-3-ethylimidazolium bromide highlights a larger shift toward innovation with care. Its unique architecture offers promise, especially as science looks for solutions that balance performance, safety, and environmental health. Whether in the lab or out in the world, the choices made around such molecules affect everyone who depends on cleaner chemistry.

Looking Beyond the Technical Data Sheets

Stepping into a chemical storeroom for the first time, the stacks of bottles and containers can feel a little overwhelming. Some chemicals handle a bit of heat or sunlight, some don’t mind the odd draft, and then there's 1-Butyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Bromide—a less forgiving guest. It’s a type of ionic liquid that brings helpful properties to research and industry, but only when handled right. Toss it on the wrong shelf or let it soak up moisture, and trouble creeps in fast. That lesson sticks with you after wiping condensation off a ruined batch, trust me.

Moisture Isn’t a Friend Here

Moisture sits as the enemy of stability for materials like this. The chemical likes to draw in water from the air—a property called hygroscopic. Leave the container open even on a moderate day and enough water can sneak in to dilute or damage the product. It’s not always about catastrophic failure; sometimes, a small change in the water content can turn consistent results into a guessing game. I learned quickly that even a crowded storeroom needs some rules. The advice: keep the bottle sealed tight whenever you can. If the product came vacuum-sealed, don’t toss the little desiccant packets. Pop them back inside with the bottle, or park the container in a desiccator alongside silica gel. That habit saves time and budget over the long haul.

Light and Oxygen—Silent Wreckers

Sunlit labs look inviting, but light and air conspire over time to break down sensitive chemicals, and 1-Butyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Bromide doesn’t appreciate long exposure either. Shield the bottle from direct sunlight and high-wattage lights. I’ve made a ritual of returning the bottle to a shaded cabinet right after measuring what I need. Oxygen can play a part in slow degradation, so crack the lid open just long enough to work, then close it snugly before moving on.

Room Temperature Sounds Simple. It Isn’t Always.

You’d think temperature control would be simple—room temperature, nothing wild. Wait until a summer heatwave or a winter freeze sweeps through an old building. Even small shifts lead to issues like crystallization or breakdown of the liquid. I've wrapped sample vials in insulating foam or stored them in climate-controlled cabinets when temperature swings strike. Solid, consistent storage keeps unwanted crystallization or slush from forming, preserving the qualities researchers depend on. If humidity or temperature gets too wild where you work, relocating the stock to a steadier space makes all the difference.

Labeling and Workflow Matter

Misplaced containers or confusing labels add to mistakes. Practical experience taught me to mark open dates and conditions right on the label. Shared lab spaces mean bottles swap hands often; clear info saves time retracing steps later. Containers meant for food or other substances shouldn’t go near this stuff. Dedicated bottles and scoops, clean and dry, keep things safer for everyone. If your group works with dozens of reagents, set aside time each month for storage checks—find leaks, condensation, or odd smells early.

Building Good Habits

No one likes the surprise of degraded reagent in the middle of a project. Prioritizing a dry, cool, and dark storage space, along with strong labeling habits and regular checks, cuts down on waste and keeps results consistent. Experience says that small, thoughtful adjustments to storage and handling outlast shortcuts every time. Those habits protect both people and experiments, long after you’ve forgotten the last chemical order.

Understanding This Chemical’s Place in Everyday Labs

Some chemicals raise eyebrows the minute their names land on a lab order. 1-Butyl-3-ethylimidazolium bromide falls among those that get flagged for a closer look, especially in research circles interested in green solvents and alternative energy technologies. With “imidazolium” in the label, it sounds almost futuristic, sparking curiosity and a little cautious respect.

For years, novel ionic liquids like this one promised eco-friendly solutions in reactions and extractions. “Green” sometimes ends up more about performance than health, and here’s where things get messy. Imidazolium salts, 1-Butyl-3-ethylimidazolium bromide included, are lauded for low vapor pressure, meaning they don’t evaporate into the air quickly—no noxious fumes wafting across the bench top. Plenty of labs appreciate that feature, me included.

Science, Not Hype, Matters Most With Safety

Research throws a mixed bag of data at safety questions. Not every lab chemical tells a simple story. The Material Safety Data Sheet for this compound signals caution: possible skin or eye irritation, maybe a risk if inhaled or swallowed in larger amounts. No one’s calling it the most toxic substance in the storeroom, but stories from folks working with related salts point to dry skin, rashes, and other irritations.

Looking around the literature, I found that this class of chemicals sometimes gets messy when spilled on skin or splashed near the eyes. Long-term exposure stories are fewer, probably because most handle it with gloves, goggles, and a bit of respect. A study by Pham et al. (2010) found certain imidazolium salts can disrupt cell membranes in bacteria and human cells when concentrations climb high enough, raising eyebrows for people working daily with these compounds.

Environmental Impact: Not Invisible, Not Ignored

Toxicity isn’t just about single incidents of skin contact. Longer-term environmental questions come into play. Imidazolium-based ionic liquids tend to stick around in water and soil. Kümmerer, an expert on environmental chemistry, points out that they are not readily biodegradable, so they can pile up in waste streams. If enough of them enter natural waterways, they may affect aquatic life by accumulating in plants or fish. Tests on other ionic liquids show some organisms—especially tiny freshwater critters—don’t fare well around high concentrations.

Mitigating Risks Daily

My own hesitation with new chemicals stems from what gets lost in translation: a label reading “low volatility” sounds safe until you remember that skin readily absorbs some ionic liquids. Responsible handling stays simple—gloves, goggles, good ventilation, and never pipette by mouth. Treat them with the same seriousness as a bottle of old-school solvent. I encourage quick cleanup of spills and secure waste storage, even if disposal rules haven't caught up with newer compounds.

Researchers should push for more toxicity data on these new chemicals. Most green solutions need that scrutiny before the “eco-friendly” badge means anything outside of marketing. Until the toxicology picture is complete, labs owe it to themselves and the planet to treat 1-Butyl-3-ethylimidazolium bromide with the respect given to any unfamiliar solvent.

Real-World Solutions and Responsible Science

Change starts by closing gaps: better training for lab staff, clear labeling, and open discussion on chemical hazards. I’ve seen mistakes shrink when chemists talk openly about their experiences and lessons learned. Donating a bit of time to review safety procedures has spared more than a few headaches—not every mistake needs to be repeated.

Standing back, innovative chemistry like 1-Butyl-3-ethylimidazolium bromide deserves both caution and curiosity. Mixing practical respect for risk with a hunger to learn—there’s the intersection where science stays both safe and bold.

Diving Into the Science of Ionic Liquids

Chemists chase better solvents every day, trying to make processes cleaner and more efficient. 1-Butyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Bromide is one of those ionic liquids that keeps popping up. Its stability at room temperature surprised me when I first saw it in a lab. By swapping out traditional organic solvents with substances like this, plenty of labs aim to cut down on volatility and flammability, which matters for both safety and reducing headaches with air regulations.

Making Industry and Research Cleaner

Industrial chemical engineers find themselves on a constant search for smarter alternatives to petroleum-based solvents. With 1-Butyl-3-ethylimidazolium Bromide, you don’t get that strong, headache-inducing smell, and the fire risk drops a lot. The cleaning power shows up most during dye extraction, cellulose processing, and sample prep in pharmaceuticals. Some years back, I saw a cellulose-to-bioethanol project struggle to break down plant fibers until the group tried ionic liquids. The yield jumped, and separations got much easier.

This compound’s appeal comes from its low melting point and ability to dissolve a wide range of substances, including tough biomolecules that regular solvents leave untouched. Scientists regularly reach for it while synthesizing metal nanoparticles. The ionic environment helps shape the nanoparticles, offering better size control—a key detail when tweaking a catalyst for maximum surface area.

Green Chemistry: Less Waste, Fewer Regrets

A big part of chemistry’s green push centers on waste reduction and handling fewer toxic by-products. Ionic liquids stick around because they can be reused several times before needing replacement, unlike volatile conventional solvents. 1-Butyl-3-ethylimidazolium bromide stands out for recycling, minimizing the costly disposal steps that industrial reactors generate. In electrochemistry, its stability serves as a reliable electrolyte for batteries and capacitors, as well as for electrodeposition of metals, because it hardly evaporates over time.

The environmental angle gets complicated if disposal isn’t done properly. Although ionic liquids earn “green” marketing, their breakdown products haven’t been studied decades out. In my experience, I have seen researchers spend more time thinking about how to recycle and reclaim these solutions in closed-loop systems. Setups with built-in purification split ionic liquid and product, letting everyone cut down on both new solvent orders and cost.

Driving Next-Gen Technology

Electronics research takes ionic liquids in new directions. 1-Butyl-3-ethylimidazolium Bromide played a role in developing nanoelectronics, acting as a solvent and stabilization medium for graphene dispersions and carbon nanotubes. The liquid environment shields delicate materials from air and moisture during assembly, which ramps up the quality and reproducibility of devices. I watched teams in materials science use this property for flexible batteries, which rely on safe, non-volatile electrolytes for wearable tech.

Catalysis used to seem like a locked box to chemical engineers, but ionic liquids have opened new doors. This particular compound stabilizes active sites in homogenous catalysts, sometimes leading to higher yields in pharmaceutical and agrochemical manufacturing. The process shifts to reactions impossible under regular conditions.

Pushing for Practical Solutions

Researchers should always think about end-of-life plans before bringing new chemicals into the picture. Encouraging industry partners to invest in solvent recovery and lifecycle studies makes a real difference to everyone downstream. Universities, too, have a responsibility to train early-career chemists to weigh safety, environmental, and economic impacts before scaling up. It isn’t just about finding a better solvent—it’s about finding a smarter way to do chemistry.