1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate: Insight and Application

Tracing the Development of Ionic Liquids

Years ago, chemistry classrooms covered solvents in broad terms—water, hexane, maybe acetone. Gradually, a quiet shift happened: researchers set their sights on materials that didn’t fit tidy categories. Out of that curiosity grew a field devoted to ionic liquids, and 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium dihydrogen phosphate (often nicknamed [BMIM][H2PO4]) carved out a space in that movement. Initial breakthroughs came toward the end of the 20th century, with the imidazolium core gaining recognition for its thermal stability and capacity to dissolve all sorts of compounds, from cellulose to metal salts. Early adopters in green chemistry circles started publishing about the salt's use as an alternative to VOC-laden solvents. Over time, with climate change looming and industries reconsidering their environmental footprints, the demand for nuanced, effective, and less hazardous solvents climbed—a trend that catapulted this class of molecules into industrial labs.

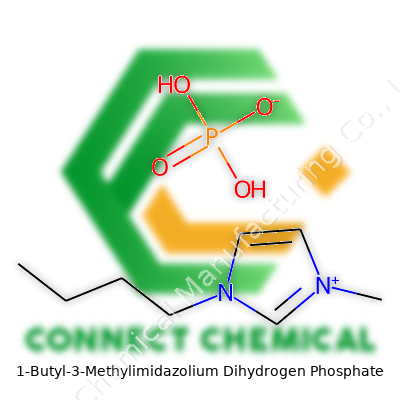

Product Overview: What Makes This Ionic Liquid Stand Out

The structure of 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium dihydrogen phosphate tells much of its story: a positively charged imidazolium ring pairs up with a phosphate anion. The butyl and methyl groups branching off the ring give it both flexibility in interactions and low volatility. Bottles containing this salt can be found at research suppliers, typically as colorless to pale yellow liquids. Compared with traditional molecular solvents, it resists evaporation and holds up under both acid and mild base conditions. For anyone who's spent late nights in the lab struggling to escape pungent, stinging vapors, it’s easy to see why these features appeal. Laboratories and manufacturers value it for its manageable viscosity, respectable conductivity, and broad utility from biocatalysis to analytical chemistry.

Physical and Chemical Properties

Pouring out a sample reveals a high density and a consistency similar to syrup, but nowhere near as sticky. Its melting point tends to land below room temperature, making it a true liquid for practical use. It dissolves ionic and polar compounds easily—cellulose, starch, and a wide range of metal complexes react well with it. The liquid remains thermally stable up to about 200°C, losing weight slowly and releasing primarily non-toxic byproducts if pushed further. Electrical conductivity sits higher than traditional organic solvents but lower than molten salts, giving a sweet spot for some applications. Its ability to accept and donate protons gives it special chemical versatility, letting it function as both a Brønsted acid and a hydrogen bond donor. For researchers exploring new reaction pathways or looking to run electrolysis processes without toxic or flammable liquids, these properties open valuable doors.

Technical Details: Specs and Labeling

On every label, laboratories look for the formula—C8H17N2O4P. Purity sits at or above 98% in most research-grade batches, often checked by NMR spectroscopy or Karl Fischer titration for moisture content. Labels warn users about the substance’s hygroscopicity; the liquid readily draws moisture out of the air. Since safe handling matters, manufacturers print hazard pictograms reminding users of possible irritation to the skin and eyes. Key identifiers include CAS number 174899-83-3, and users also refer to the product as BMIM H2PO4 or 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium phosphate. Packaging almost always involves airtight, moisture-proof bottles, sometimes under dry nitrogen for extra shelf life. Breaches let the liquid absorb water, changing its properties and sometimes skewing reactivity—anyone planning serious experiments checks for this before running critical tests.

How Labs Make BMIM H2PO4

Synthesis follows a straightforward path, making it accessible to both industrial and academic labs. The process often starts with 1-methylimidazole, reacted with 1-chlorobutane to form the intermediate [BMIM]Cl. The next step replaces the chloride with a phosphate: mixing with phosphoric acid accomplishes the swap. Several washes—usually with ethyl acetate or another non-polar solvent—remove residual byproducts and give a cleaner end product. Working up the final mixture requires methodical drying under reduced pressure or in a vacuum oven, since any lingering water can skew the ionic liquid’s behavior. The synthesis relies on no rare reagents and scales well, so bottlenecks rarely stem from production. From my experience, even small undergraduate labs can handle this preparation safely with good ventilation and PPE.

Chemical Reactions and Modifications

BMIM H2PO4 doesn’t just serve as a solvent. The dihydrogen phosphate anion allows for a range of acid-catalyzed transformations, including esterification and transesterification. As a supporting electrolyte, the ionic liquid stabilizes high concentrations of dissolved metal salts, making electrodeposition of rare metals more efficient and less prone to yield loss. Creative minds have built hybrid materials by mixing this liquid with solid acids or organic polymers, leading to proton-conducting membranes for fuel cells and solid-state batteries. The imidazolium cation also tolerates attachment of other alkyl groups or functional handles, shifting solubility, acidity, or thermal resistance depending on the application. Better-performing lubricants, extraction fluids, and ionic gels emerge from these sorts of explorations.

Other Names and Related Products

Over the years, the chemical picked up several aliases—BMIM DHP, 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium phosphate, or simply imidazolium-based phosphate ionic liquid. Some catalogs group it with other imidazolium phosphates, while others make clear distinctions based on the anion’s composition and acidity. The [BMIM] motif appears in dozens of related ionic liquids, united by the core imidazolium ring and branched only by the anionic partner. Even small changes to the anion or side chains push the liquid’s behavior in new directions, so accurate labeling and CAS numbers matter for reproducibility and safety, especially as similar-sounding compounds can sport very different properties when put to the test.

Safety Measures and Regulatory Guidance

Even though imidazolium ionic liquids generally show low volatility and don’t catch fire easily, they still demand care. Contact with skin may lead to mild irritation after prolonged exposure, and splashes in the eyes can sting. Labs practicing good hygiene—gloves, goggles, and proper ventilation—rarely run into trouble. Waste disposal regulations treat BMIM H2PO4 as a specialty chemical; users should avoid pouring it down the drain and instead send spent samples to solvent recycling or hazardous waste collection. I’ve seen researchers get tripped up by the compound’s tendency to soak up moisture and gradually change composition, so clear labeling of opened containers and routine checks for cloudiness or discoloration help maintain experiment integrity. Regulatory agencies have yet to classify the substance as a major environmental threat, but they recommend minimizing release to water systems as ionic liquids can persist and potentially impact microbial communities.

Real-World Uses and Growing Applications

Out in industry, uses stretch far beyond the textbook examples. Early work in biomass processing used BMIM H2PO4 to break down plant fibers—especially cellulose, once thought impossible to dissolve outside of nasty sulfurous broths. This changed paper recycling, bioplastics, and even biofuel labs. The liquid’s acidic character gives it value for catalyzing esterification and transesterification, especially in the conversion of vegetable oil to biodiesel. In battery research, materials scientists test membranes and electrolytes built on imidazolium core chemistry for next-generation lithium and proton batteries. A colleague of mine explored its use in stabilizing enzymes for food processing, noting a dramatic increase in both activity and lifespan versus traditional water-based mixtures. Water treatment facilities look to these compounds for streamlining separations, and even pharmaceuticals see promise in selective drug extraction and crystallization steps. Industry reports describe a slow but steady shift towards using ionic liquids to cut VOC emissions and improve worker safety. It’s not every day a material makes such a broad leap, spanning chemistry, engineering, and environmental science.

On the Cutting Edge: Research and Ongoing Development

Every conference season, new posters and talks cover tweaks to the BMIM backbone—adding hydrophobic chains, merging with task-specific ligands, or blending with nanomaterials to form gels and films. Researchers from fields as disparate as catalysis and environmental engineering borrow clever tweaks developed in chemical synthesis labs. At the bench, teams push for designs that cut costs, reduce side reactions, and simplify recovery at the end of processes. For instance, using BMIM H2PO4-based ionic liquids in biomass deconstruction now plays a role in pushing second-generation biofuels closer to widespread reality. Analytical chemists chase improvements in selectivity for sensors by anchoring antibodies or dyes onto imidazolium-modified scaffolds. The diversity of ongoing research speaks to both the flexibility and the real challenges: lowering cost per kilogram, tuning degradation profiles, and navigating evolving regulatory expectations make up just a slice of the day-to-day work. Funding agencies and journals expect not just improvements in process efficiency but also concrete gains in sustainability metrics.

Toxicity Insights and Ongoing Safety Research

Chemical safety data sheets for BMIM H2PO4 spell out low oral and dermal toxicity in mammalian cell lines, supported by studies in laboratory rodents. Researchers point out that ionic liquids don’t easily evaporate into the air or absorb through unbroken skin, so exposure risks diverge sharply from classic solvents. Still, aquatic toxicity remains an open question. Some reports write about minor impacts on the metabolic function of bacteria and algae exposed to high concentrations. Long-term fate in soil and water, as well as the effects on useful microbes, sits at the center of debates in academic journals and at environmental policy hearings. Labs increasingly build routine toxicity screening into their workflow, measuring endpoints beyond simple LD50—think enzyme inhibition, reproductive effects, or bioaccumulation potential. The hope is to catch subtle problems early, rather than repeating the mistakes of legacy solvents that once seemed harmless. Routine updates to safety data and growing calls for transparency push the field to improve best practices and reporting standards.

Eyes on the Horizon: What the Future Holds

The push for greener chemistry doesn't look likely to lose steam. BMIM H2PO4 and relatives may not reach every home or factory, but every step away from volatile, hazardous solvents helps. Teams worldwide dig into long-term durability, recyclability, and environmental fate, hoping to solve sticking points around cost and lifecycle analysis. Some manufacturers invest in closed-loop systems, recapturing ionic liquids for reuse and driving down the environmental and economic overhead. In larger-scale projects, researchers look toward custom-blended ionic liquids to enable processes like plastic recycling, rare earth recovery, or even direct air capture of carbon dioxide—goals that, if realized, could dramatically change energy, manufacturing, and waste management systems. As knowledge grows and the price for fine chemicals keeps dropping, BMIM H2PO4 stands as both a sign of scientific ingenuity and a practical tool for building a cleaner industrial future. Many feel optimistic about changing the conversation around chemicals in society: less fear, more thoughtful design, and a drive to turn insights from the lab into safer products and better jobs. Remaining questions and bumps in the road only reinforce the importance of research that pulls in toxicologists, engineers, and policymakers to steer development in positive directions.

A Quiet Revolution in Chemistry

1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium dihydrogen phosphate rarely shows up in mainstream conversation, but chemists know it well. This liquid serves as part of a family called ionic liquids. Unlike water or oil, it doesn’t evaporate at typical room temperatures, making it handy in certain tough chemical jobs. Using it keeps messes contained and reduces emissions, a big win for workers and the environment.

Game Changer for Green Chemistry

Many chemical plants use harsh solvents that pollute air and water. Replacing them with something safer has always topped my list of wishes. This ionic liquid steps up in places where old-school solvents struggle. It handles intense chemical reactions without releasing toxic fumes. During my time helping students in a university lab, switching to safer solvents made a huge difference. Not only does it make experiments safer, but waste is easier to manage.

Academic papers support this. Researchers use it to break down cellulose from wood or plants, which helps in biofuel production. Regular solvents can’t do this job as efficiently. One study from the journal Green Chemistry shows 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium dihydrogen phosphate making bio-refining more practical. Agricultural waste costs less, and fewer chemicals leak into the ground or water supply.

Better Extraction and Synthesis

In my experience, getting valuable stuff out of natural materials requires finding the right liquid for the job. This ionic liquid makes life easier for folks in pharmaceuticals, dye extraction, and even food flavor production. Companies working on extracting active chemicals from herbs switched to this ionic liquid because it’s less toxic and gentler on sensitive compounds.

If you have ever tried making something delicate in the kitchen and needed a specific oil or water mix, you know the struggle of choosing what works best without ruining the dish. Chemists face a similar challenge. Picking 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium dihydrogen phosphate helps preserve what matters, while creating fewer byproducts.

Supporting Renewable Energy Research

Energy storage and conversion depend on the right materials. Leading labs, including the one where I started my career, test this ionic liquid in batteries and solar cell research. It keeps devices stable even during harsh temperature swings. Academic results show improved performance in certain fuel cells, helping push clean energy closer to scale.

The energy industry chases materials that last longer and perform safely under constant use. In my hands-on work at chemical companies, crews always pushed for solutions that avoid accidental fires or chemical leaks. Using this kind of ionic liquid makes their jobs less risky, both in the factory and for people using the final products.

Challenges in Adoption

Change doesn’t come easy. While this ionic liquid has promise, it sometimes costs more than traditional chemicals. Many smaller labs stick with what’s familiar, even if it means higher hazards. I’ve seen budgets stall green initiatives, despite the desire to do better. That said, researchers and policy makers have a chance to tip the scales. By directing funding and regulations toward safer alternatives like this, we can see wider adoption and healthier workplaces.

Where Things Head Next

1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium dihydrogen phosphate stands at the frontier of making chemistry cleaner. As people demand safer products, and as economies search for smarter materials, this ionic liquid deserves a closer look. Giving it room to grow could change the face of everything from basic science projects to biofuel refineries and energy tech. Seen through the benchmarks of sustainability and worker safety, the case grows stronger each year.

The Realities Behind the Chemical Name

Just reading the name 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate for the first time might bring back memories from the high school chemistry lab. It’s one of those ionic liquids popping up in labs and industry lately, grabbing attention because it brings together useful properties like low volatility and the ability to dissolve a wide range of stuff. But, as with any chemical, the question of safety jumps out immediately, especially for folks like me who’ve worked near a fume hood and seen the difference a safety sheet can make.

Direct Risks: Touch, Smell, and Spills

This isn’t a chemical you see sitting on hardware store shelves. In fact, most people who handle it regularly are in research labs or industrial plants exploring new ways to clean up processes or recycle materials. Here’s the reality: 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate has some clear safety concerns. It may not boil off into the air at room temperature like solvents such as acetone or ether, but that doesn’t mean it’s harmless. Through personal lab work, I’ve learned that the stuff can cause lumps or irritation if it pools on your skin for too long. It’s not something to splash on your arms or wipe up with bare hands. Laboratories usually flag it as harmful, especially since repeated contact can dry out or even damage your skin.

Breathing in vapors might not be as obvious compared to classic solvents, but that low smell shouldn’t fool anyone. Ionic liquids can float around silently, and nasty rashes or headaches sneak up in a poorly ventilated room. There’s also no reason to taste or sniff these compounds. If you value your sense of smell, it’s better to keep noses, eyes, and tongues away.

Long-Term Questions

Research gives some good news and some unknowns. Toxicity studies on chemicals like this haven’t shown dramatic, immediate poisoning in small doses, with some suggesting they pose less risk than mercury or cyanide. Still, “less risky” isn’t safe. Long-term effects prove tricky to nail down. Chronic exposure might hit organs or disrupt the ecosystem, especially once these chemistries leave the lab. Ionic liquids like this one don’t break down as fast as water-based chemicals, raising eyebrows about wastewater and soil build-up. In my own circle, cautious colleagues opt for the same gloves and goggles you’d use for worse chemicals, just in case.

Doing the Right Thing

So, does a researcher or worker have to worry? The answer always lands: respect the material. Safety goggles, gloves, lab coats, and fume hoods belong in every workday with ionic liquids. Cleaning up spills with paper towels and tossing them in the trash might seem fast, but all that runoff can create disposal headaches. Dispose as a hazardous waste, according to the rules set by your institution or local authority.

It’s tempting to rely on the greener reputation of ionic liquids. Some industries praise them, pointing out that they don’t catch fire the way older solvents do. But as green chemists have told me in blunt terms, “green” means less risk, not no risk. Proper training matters as much as reading any data sheet or material label. If staff aren’t sure how to handle these liquids, someone needs to step up and give a walkthrough, simple as that.

Where Do We Go from Here?

Chemical safety can often sound tedious, but it’s the only way to avoid real accidents. In my own experience, transparency and routine make all the difference: instead of hushed whispers about burns or rashes, share every close call in safety meetings. Good ventilation, fresh gloves, and careful disposal habits turn a complicated name like 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate into just another tool, not a lurking danger.

Direct Impact on Safety

I walked into a storeroom years ago—my first job at a small paint factory. I spotted plastic bins piled up near the back door, labels peeling off, mysterious liquid bubbling inside one. The smell alone could knock you over. That experience hammered home the point that storing chemicals isn’t just about following rules; it’s about keeping people safe. One oversight can trigger disaster. Just last year, a warehouse fire in my city traced back to improperly stored solvents. That fire put emergency crews at risk and forced families to evacuate for days.

Paying Attention to Compatibility

Certain chemicals just do not get along. Acids and bases, for instance, react violently on contact. Some oxidizers even react with everyday materials, like rags or cardboard. Storing calcium hypochlorite (pool chlorine) next to anything flammable invites an explosion, literally. Paints, fuels, and cleaning agents often call for their own dedicated shelves for that reason. OSHA makes it clear: segregation and clear labeling are non-negotiable.

Shelf Life and Stability

Storing a chemical the wrong way shortens its life. Moisture sneaking into a bag of powdered reagent, or sunlight cooking a bottle of hydrogen peroxide on a windowsill—both spell trouble. Decomposition isn’t always visible, and the dangers aren’t always obvious, but even minor changes in temperature or humidity add up. Most labs and stores rely on climate-controlled rooms and airtight containers. Some gases belong in cylinders, chained upright on cold concrete, far from exits. Alongside safety, maintaining shelf life protects investments: chemicals aren’t cheap. Wasting a drum because of poor storage eats profits fast.

Labeling and Documentation

I still keep a habit picked up from a former coworker: every bottle labeled with full product name, hazard pictograms, and date received. It isn’t about obsessing over paperwork—the info saves time and reduces accidents. Consider a busy science classroom. Swapping out one colorless liquid for another because of a smudged label could land a student in the hospital. Good labeling paired with an inventory log, whether digital or paper, anchors accountability. In regulated industries, that documentation also stands between a business and a crippling fine.

Regulatory Guidelines: The Rulebook Keeps Changing

Keeping up matters. Authorities like OSHA, NFPA, and the EPA constantly refine their recommendations. I’ve seen the fire inspector send a company scrambling because guidelines had changed since their last review. Before storing anything, I always recommend checking the Safety Data Sheet; it lists basics, from ideal temperature to what to do if something spills. Not every chemical asks for the same isolation or ventilation, but those sheets paint a clear picture.

Common-Sense Measures Anyone Can Use

Open containers and careless spills always creep up when staff skip the basics. Most storage routines come down to simple steps: seal every lid tight, set liquids low to the ground, keep the shelves uncluttered. Ventilation tricks go beyond opening a window; some chemicals demand exhaust hoods. Spill kits, eyewash stations, fire extinguishers—each one acts like an insurance policy for workplace health.

What Works in Real Life

On a job site or in a small business, talking storage sounds tedious until something goes wrong. I’ve seen managers invest in steel cabinets with spill containment sumps underneath because plain plywood shelves absorbed leaks and started to sag. Simple upgrades, like anti-tip trays and corrosion-proof paint, change the equation. Mistakes taught me this: treat chemical storage as a daily habit, not a yearly audit. Training staff regularly and sharing past near-misses keeps everyone sharp.

Science in the Workplace Needs Street Smarts

Lab life often involves handling stuff with long names and even longer lists of safety concerns. 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate falls into that category. This ionic liquid sees use in research, green chemistry, and some battery tech, but tossing it down the drain won’t cut it. Growing up around mechanics, I learned early on that ignorance about what went down the sink or gutter usually brought consequences. We risk the same—the chemical world doesn’t forgive shortcuts.

Why Tossing in the Trash Isn’t an Option

A lot of folks bump into a bottle of something they don’t recognize and figure, "Mix it with enough water, no one cares." This mindset leads to polluted waterways or damage to local treatment plants. The same stuff that makes these salts useful—their low volatility, strong ionic nature—spells trouble for natural breakdown outside controlled settings. Ionic liquids stick around, possibly leaching toxic bits or messing with aquatic life if they get past water treatment.

The Law Has Teeth and a Long Memory

I’ve worked with custodians scrubbing up after careless labs, hearing stories about fines, lawsuits, and embarrassed institutions. Regulators track down origins of illicit discharges. Even the best intentions can land a person or team in deep water if local codes or national rules around hazardous waste aren’t followed.

Follow the Hazmat Routine

Disposal turns into a simple task when staff stick to a set process. Bottle up unwanted ionic liquid in a robust, sealed container. Match it with a durable, accurate label: full chemical name and concentration. Pouring this down the drain with wishful thinking isn’t safe. Lab supervisors or residents might collect these bottles in a lockable cabinet, away from sunlight and HVAC vents.

After collection, trained waste agents pick up the containers. They ship it to licensed hazardous waste handlers, who either neutralize it using specialized treatments or incinerate it in high-temperature kilns. These pros track every movement, recording details for audits and safety reviews. None of this is as snappy as tossing it out, though it beats explaining a spill to a news crew.

Prevention Keeps Headaches Away

Best fix: avoid amassing more than needed at project start. Small-lot ordering, sharing between neighboring teams, or asking chemical supply partners about take-back programs saves headaches. Where possible, switch to greener, less persistent chemicals, especially for educational work or large processes.

Bigger Picture—Why Safe Disposal Shapes Trust

I once tutored students who wondered why fuss so much about small bottle clean-outs. That discipline builds a laboratory’s reputation and trust with fire marshals, funders, and the wider public. Nobody wants their neighborhood stream fouled up or new regulations slapped on the field because of a lazy mistake.

So much progress depends on safe practices. Lab managers and researchers who stick to the rules not only keep regulators happy—they protect themselves, their jobs, and the water we all drink. Chemical know-how means more than mixing; it means caring about what happens after the experiment ends.

Facts About Purity in Real Lab Settings

Anyone who's spent time around a chemical bench knows purity means more than a number on a data sheet. Labs sourcing 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium dihydrogen phosphate (often written as [BMIM][H2PO4]) typically look for at least 98% purity. Reagent suppliers offer certifications and batch analysis, but even a fraction of a percent matters in practical chemistry. Lower purity pulls in byproducts like unreacted imidazole rings, side-chain residues, or trace metals from glassware and process lines. These tiny changes throw off delicate measurements, block catalysis, and lead to irreproducible results.I’ve seen plenty of research get derailed by a supplier cutting corners or a poorly stored batch. Even the best-wrapped ampoules take a hit after exposure to damp air. Ionic liquids like this one often hydrate quickly—a room left unsealed for an afternoon can start throwing impurities into the mix. So, labs running analytical tests such as NMR, FTIR, or ion chromatography put a premium on batch verification before every critical experiment.

What Does It Look Like in Everyday Use?

At room temperature, 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium dihydrogen phosphate arrives as a clear, viscous liquid. It isn’t flashy—sometimes a faint yellow tint shows up, especially if stored too long or exposed to light. Most researchers expect a nearly colorless material with no solids or visible cloudiness, because haze signals either water uptake or chemical breakdown.The viscosity stands out. It's thick, a lot like vegetable oil. Try pipetting it and the difference becomes obvious—plastic tips don’t drain smoothly, and glassware needs a lot more patience. Pour a little from one beaker to another, and the drag feels real. This unique texture comes from its ionic character and hydrogen bonding. Too much water or contamination thins it out, signaling it's time to purify or order a fresh batch.

Why Purity Matters For Research and Industry

Ionic liquids have picked up steam for green chemistry, electrochemistry, and catalyst research. Their low volatility and thermal stability make them useful in tough environments. Still, impurities cripple their most prized benefits. Water slashes performance in battery electrolytes. Trace metals in a supposedly pure sample can keep entire labs chasing false leads. If you work in synthesis, even a small impurity shifts product yields and selectivity. It costs labs valuable time, and, in large-scale applications, translates to lost revenue.Some teams have switched to in-house recrystallization and vacuum drying to push toward “ultrapure” specifications. While expensive and time-consuming, that extra effort pays dividends for consistent, repeatable performance. I’ve seen postdoc teams set up in-line screening using ion chromatography and Karl Fischer titration to check for phosphate purity and moisture, so future batches stand up to scrutiny.

Troubleshooting and Solutions

The best way to keep high purity? Keep supplies tightly sealed, away from air and light, and stored in clean, dry containers. For large operations, dedicated storage and positive pressure dry rooms help block out humidity. Small labs sometimes team up, running joint quality checks on bulk orders before splitting them up. If a batch falls short, methods like rotary evaporation, column purification, or reprecipitation using dry solvents help salvage valuable material.No one gets perfect purity every time, but a little caution saves a lot of trouble down the line. In research and industry alike, betting on the highest quality upfront turns out cheaper than patching mistakes later.