1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate: Evolution, Operations, and the Road Ahead

Historical Development

Long before the chemical industry buzzed about ionic liquids, traditional molecular solvents held center stage in labs. As environmental concerns gained urgency, researchers and manufacturers dug deep for alternatives that could offer low volatility, recycling potential, and safety. Born from this search, 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate—or BMIM TFA—emerged alongside its ionic liquid cousins in the late 1990s. Early curiosity quickly turned into real opportunity as chemists noticed how these salts functioned under room temperature, handling both organic and inorganic materials easily and resisting thermal breakdown. Over two decades on, BMIM TFA continues to spark debate about cost, environmental impact, and technical fit for industry processes.

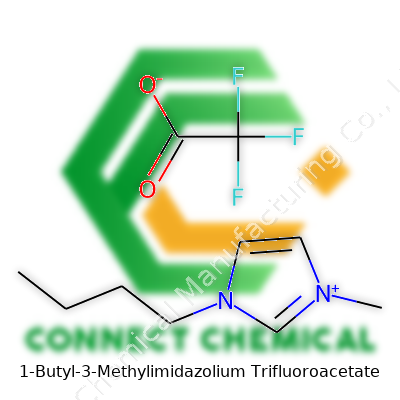

Product Overview

At the heart of BMIM TFA is an imidazolium cation paired with a trifluoroacetate anion. As with many ionic liquids, BMIM TFA delivers distinct winner traits: it flows at room temperature, it doesn't catch fire easily, and it brings low vapor pressure to the table. Chemists today keep it within reach for cases needing both effectiveness and lower risk of sending fumes into the workspace. The trifluoroacetate part offers extra solubility for polar and non-polar molecules, which almost feels like having an ace up your sleeve in solvent applications.

Physical & Chemical Properties

BMIM TFA forms a colorless to pale yellow liquid that, on handling, feels almost oily. Its melting point hovers below room temperature, making it easy to manipulate without heat. The compound resists evaporation, with a boiling point over 300°C under standard pressure. It mixes smoothly with water and polar organic solvents, but the trifluoroacetate anion injects a mild acidity that shapes which reactions it can take part in. Unlike some ionic liquids with halide counterions, BMIM TFA offers a non-chlorinated path, which, from direct industry experience, reduces downstream corrosion and equipment wear.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Marketed with a chemical formula of C10H15F3N2O2, BMIM TFA typically ships with purity declarations above 98%. Look for the CAS number 174899-83-3 for traceability. Labels must include water content (under 0.5%), specific gravity benchmarks, as well as any stabilizers added to protect batch stability. Regulatory data on storage reflect its sensitivity to strong oxidizers and moisture, with manufacturers recommending amber glass or HDPE containers. Material Safety Data Sheets highlight proper protective gear—nitrile gloves, goggles, and, if splashing threatens, face shields.

Preparation Method

Making BMIM TFA starts with 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium chloride and sodium trifluoroacetate in a straightforward metathesis reaction. Mixing these in water and stirring yields BMIM TFA and sodium chloride as a byproduct. Purification typically runs through several extractions and drying sequences, funneling out inorganic salts and reducing water content. Experience in chemical labs underscores the benefit of thorough purification—residual chloride can act as a silent saboteur in sensitive catalytic runs, so ion chromatography after synthesis makes a real difference.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

In synthetic work, BMIM TFA earns its keep as a solvent for cellulose dissolution, transition metal catalysis, and CO2 capture. That mild acidity, stemming from the trifluoroacetate, often guides substrate activation without overwhelming the mix. Some chemists swap in different alkyl chains or modify the imidazole core to tune hydrophilicity, making variants that fit wider application profiles. Others push the boundaries by using BMIM TFA as both a solvent and reagent, allowing the trifluoroacetate group to enter target molecules. Each adjustment demands re-validation—especially where the scale ramps from milligrams to kilograms.

Synonyms & Product Names

Outside the lab, 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate goes by a few aliases: BMIM TFA, [BMIM][TFA], or even simply Imidazolium Trifluoroacetate. Across datasheets and supplier catalogs, these names pop up interchangeably. Some global suppliers add suffixes to indicate water content or purity grade, just as pharmaceutical and electronics markets demand. In my daily workflow, sorting by CAS number cuts through the confusion, helping to pinpoint genuine BMIM TFA and sidestepping mixed-up batches.

Safety & Operational Standards

Safety practices around BMIM TFA come from a blend of laboratory knowledge and evolving regulatory frameworks. While low volatility keeps inhalation hazards low, accidental contact with skin still triggers irritation, and the compound’s acidity can bite over time. Labs running repeated syntheses use mechanical ventilation and train staff on spills and neutralization. Waste handling lands high on the checklist—ionic liquids don’t simply float off down the drain, so waste collection and third-party disposal align with both company policy and national environmental law. Accident records and feedback from safety officers continue to improve the operational checklist, underlining the point that one incident can spoil a year’s best intentions.

Application Area

BMIM TFA fills a gap in several scientific corners. In biomass research, it breaks down cellulose for biofuels, turning tough agricultural waste into fermentable sugar streams. The electronics sector values it for dissolving polymers during precision etching. Pharmaceutical labs use it for extraction and purification runs, dodging volatile organic solvents whenever they can. In CO2 absorption technologies, BMIM TFA captures greenhouse gases from industrial streams more efficiently than simple alkanolamines. Speaking from research experience, once a process absorbs the step change to ionic liquids, the technology often stays, as productivity gains, health benefits, and downstream yields add up.

Research & Development

Academic teams keep finding ways to push BMIM TFA’s boundaries. Some investigate new catalysts for biotransformations; others test it as a recyclable medium for advanced organic syntheses. Process engineering experts juggle cost, purity, and reuse, trying to stretch every barrel’s value. Journals report on upscaling challenges—fouling, spent liquid quality, and minor decomposition products can all sap momentum at industrial scale. Still, collaboration between universities and industry has never been higher, with grant funding targeting ionic liquids that promise both green credentials and measurable economic return.

Toxicity Research

Early studies on BMIM TFA held out hope for low human and environmental toxicity. Subsequent work revealed a need for more nuance. Acute toxicity tests in fish and bacteria suggest moderate risk—safe zones exist, but over-application or disposal missteps concentrate the hazard. Some researchers focus on long-term bioaccumulation, with results varying by species. Lab techs learned early to monitor personal symptoms. Regulatory scientists demand more in vivo data and urge transition to minimal-environment-release pathways. The best labs repeat this work as formulations and manufacturing processes shift, knowing that new impurities or side-products might pose surprise challenges.

Future Prospects

Looking forward, BMIM TFA will keep drawing attention wherever safe, high-performance solvents matter. Industrial chemists eye it for battery electrolyte development and as a key player in green chemistry platforms. Questions of scalability, cost reduction, and waste minimization never really fade, but each batch tested, each patent filed, brings answers closer to hand. The environmental movement also leans on such advances, asking for proof that echoes in long-term safety records. In my own work, successes and setbacks both reinforce the insight that materials like BMIM TFA directly shape a sustainable, smarter manufacturing future, provided transparency, oversight, and ongoing research never get left behind.

What Exactly Is This Chemical?

Most folks outside chemistry labs haven't heard of 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate. It’s not something you grab off a grocery shelf. Scientists label it as an ionic liquid, meaning it stays in liquid form at room temperature thanks to its unique ionic structure. Instead of evaporating like water or traditional alcohols, it remains steady, rarely gives off strong fumes, and holds its own even under high temperatures.

Why Do Chemists Want It?

One of the standout features of this chemical: it’s a game-changer for dissolving tough plant materials such as cellulose, the rigid stuff in wood and paper. The average lab solvent avoids this challenge. Through trial and error in grad school, I saw colleagues struggle to break down bamboo fibers. Acetone and ethanol did little. This is where ionic liquids like 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate step up. Drop a bit into shredded wood pulp or paper, and it disassembles the cellulose at the molecular level. That opens all sorts of possibilities for turning old newspapers or wood scraps into something new, like biofuels, textiles, or specialty chemicals.

Cellulose Processing in Bioeconomy

The world makes a mountain of paper, agricultural waste, and wood chips every day. Most ends up tossed or burned. Pulling valuable sugars from these scraps remains tough, mainly because the cellulose refuses to dissolve. According to research by the American Chemical Society, this ionic liquid stands out for breaking down over 20% cellulose in a mixture—a higher figure than many other solvents on the market. That’s a jumpstart for biorefineries looking to turn cheap plant waste into useful products without toxic byproducts. In terms of real impact, using this chemical could nudge more countries to recycle harder-to-use paper sources and slash reliance on fossil fuels for making plastics and fuels.

Lab Experience and Industry Shifts

My own time in a university research group brought these solvents to life. We ran tests to cleanly dissolve cellulose and lignin without making a mess or giving off noxious fumes. Handling classic solvents like dioxane risked headaches and skin irritation. The switch to ionic liquids felt safer and healthier, not just better for research but for technicians working eight-hour days. Industrial researchers, seeing similar benefits, now incorporate this chemical into pilot projects, especially for sustainable materials research.

Risks and Where to Go From Here

No breakthrough skips risk. Production cost still runs higher than for traditional solvents, which slows wide-scale rollout. Disposal brings up questions of toxicity and recovery. Scientists keep looking for recycling techniques that would keep this chemical cycling through multiple rounds, slicing waste and expense. At the same time, universities and chemical companies share their findings to improve recovery and treatment methods, keeping environmental impact low.

Looking Ahead

Real progress often sneaks in through these unsung advances. By offering a tool to unlock trapped plant sugars, 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate makes a strong case for cleaner, greener industries. Lab results and startup ventures show that solutions built on clever chemistry, when done with an eye for safety and sustainability, inch us closer to a future where garbage piles inspire possibility instead of problems.

What Kind of Chemical Are We Dealing With?

1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate pops up in labs that focus on green chemistry, cellulose processing, and even in some battery research. If you're around chemists, you’ll hear this one called an “ionic liquid.” Basically, it has almost no vapor pressure and melts at a lower temperature than table salt. On paper, that sounds less risky. Low vapor means less of it wafting into your lungs.

The Real Risks in Handling

Looks can deceive in chemistry. Despite the stable reputation of ionic liquids, trifluoroacetate makes things trickier. Fluorinated chemicals sometimes trigger skin irritation and do not play nice if splashed in your eyes. Some colleagues told me after working with it for hours, they felt mild headaches. These symptoms vanished quickly, but the fact remains—most ionic liquids do not have decades of safety data, unlike, say, sodium chloride.

The trifluoroacetate component should raise your guard. Trifluoroacetates, cousins to trifluoroacetic acid, land on the spectrum of strong organic acids, meaning even a small splash can sting. Add in that ionic liquids often carry impurities—maybe the unreacted starting material, maybe trace acids from synthesis—makes the risk unpredictable between batches. Every bottle brings fresh uncertainty.

Ignorance Doesn’t Equal Innocence

The Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS) can only tell what’s already known. For 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate, data on long-term exposure, inhalation, or chronic issues runs thin. In my old research group, our policy was to treat all imidazolium-based solvents with gloves, lab coats, and goggles—no shortcuts, even for five-minute bench work. Many labs echo that: treat newish chemicals as “guilty until proven safe.”

Environmental scientists keep sounding the alarm on persistent organic pollutants, and some ionic liquids resist breaking down in nature. Nobody wants to create the next PFAS mess by flushing chemicals down the drain. Waste streams need attention. We pooled used ionic liquids and shipped them out with other hazardous waste rather than sending them through regular disposal.

Better Safety Starts with Good Habits

Solid ventilation, diligent glove use, and goggles do most of the heavy lifting for personal protection. Those basic habits make the difference between a student finishing a project or heading to the campus clinic after a careless skin splash. I’ve seen one slip with a “benign” solvent turn into chemical burns, because the glove had a small tear.

Label every bottle, check expiration dates, and inspect for weird precipitates before pipetting. Even a faint whiff can give you headaches if you spend all afternoon hunched over a flask. If any splashing or spills happen, immediately rinse the area with plenty of water and seek medical attention—even minor irritation might become a problem over time.

Heading Toward Greater Transparency

Push manufacturers for clearer, more robust safety data. Request testing on biodegradability, long-term inhalation risk, and skin absorption. If more users demand open test results, companies and academic suppliers will step up. Until then, approach 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate with caution, treat it with the same respect you’d give a new power tool, and never cut corners just because “everyone in the lab uses it.” Your health depends on it.

Why Purity Isn’t Just a Technical Line on a Data Sheet

Talking about the purity of specialty chemicals like 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate (BMIM TFA) has a direct impact on how research pans out or whether an industrial process avoids grinding to a halt. Whether you’re working in a university lab, trying to figure out a new catalyst system, or mixing up ionic liquids for pilot-scale separations, a clean sample gives you control and peace of mind. Any single impurity might seem trivial, but it can send yields tumbling, cloud up data, or even damage expensive setups.

On paper, people often claim a “99%” purity for this compound. That single number doesn’t tell enough. I’ve worked with BMIM salts sourced from different suppliers, and a side-by-side comparison taught me how much difference traces of the wrong contaminant can make. Some samples performed predictably every time. Other bottles, all marked “99%,” sabotaged cell cultures or caused unexpected shifts during NMR analysis. The unfortunate truth: that missing 1% could be traces of water, halides, residual starting materials, or dark, oily byproducts nobody wants near their experiment.

Testing What Matters

One time, I ordered a batch for enzyme research, and we ran a straightforward NMR and ion chromatography before even thinking about setting up our actual reactions. Just a half percent of leftover imidazole changed the pH and left us scratching our heads. There’s a lesson there. Real purity is more than a label or some paperwork—it’s about whether your work holds up under scrutiny, whether controls behave as you expect, and whether scaling up goes smoothly.

Routine vendors run HPLC, NMR, and water content checks, but not every lab does. It’s easy to assume your chemical source did the job, but skipping due diligence can waste weeks cleaning up the fallout. When I coordinated with a pharmaceutical partner in 2021, their process chemists spent almost as much time vetting raw material quality as they did designing syntheses. That’s how much experience has taught them about the domino effect of overlooked contamination.

Implications Throughout Science and Industry

In ionic liquid-based biomass pretreatment, BMIM TFA purity controls everything from enzyme activity to how well you recover sugars. In analytical chemistry, the tiniest contamination misleads folks about extraction efficiency or retention times. It isn’t rare to see journals describing problems that only get solved after rerunning experiments with a higher-grade chemical. So if a paper claims “enhanced selectivity” or “exceptional yields” based on BMIM TFA, readers and reviewers should wonder how thoroughly those chemicals got profiled. Mistakes in this area lead to unrepeatable science.

How the Field Can Do Better

From experience, procurement should demand full certificates of analysis, not just a purity percentage. Supplier audits and independent batch verifications cost time, but they pay off. For labs without access to sophisticated gear, working with a trusted supplier—not chasing the lowest price—protects project timelines and budgets. Sharing detailed characterization results when publishing lets others duplicate success or catch issues before they spiral. For teams running production, on-the-spot moisture checks and routine contamination screens set a baseline for consistency.

Quality in any scientific pursuit hinges on transparency. For chemicals like BMIM TFA, real purity means sharing specifics and never sweeping outliers under the rug. Projects thrive when everyone, from student to technical manager, treats purity as a foundation—not just a selling point.

Real Hazards Call for Real Care

I’ve seen my share of chemical cabinets over the years. Plenty of labs end up taking shortcuts—using old jam jars, stuffing valuable compounds next to bleach or in sunlight. That might work for table salt, but things quickly turn risky with more complex chemicals like 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate. This is a room-temperature ionic liquid, known for its role in cellulose processing, advanced battery design, and as a green solvent in synthesis. It sounds harmless enough, but don’t underestimate what improper storage can do.

The Enemy: Water and Heat

Moisture creeps in everywhere, and ionic liquids don’t take kindly to it. I learned this the hard way testing a batch for residual water content: Even exposure to the air for a few hours sent the numbers up, ruined the solvent’s efficiency, and triggered a long session with a vacuum pump. Water breaks down the performance, but more pressing, it can trigger unpredictable reactions with some metals or acids. Heat is no friend, either. Over time, higher temperatures push decomposition and can let vapors out—exactly what you don’t want indoors.

What Good Storage Looks Like

Industry guidance and years of lab bench mistakes say the same thing: store the bottle in a cool, dry place, out of direct sunlight. No window ledges, no radiator shelves, no open-topped flasks. Standard operating procedure means sealed bottles—polyethylene or glass both work—as long as the cap actually fits. I always bake the bottles dry before adding fresh ionic liquids, then label them with the opening date. Shortcuts with taped-on caps and mystery containers have ended badly every time.

I recommend using a desiccator or at least a dry cabinet. Silica gel, molecular sieves, or simple calcium chloride can keep the humidity away if kept fresh and not ignored for months. In shared spaces, keep incompatible chemicals away—acids, bases, strong oxidizers, and metal powders should stay on different shelves—or, better yet, in different rooms. I’ve seen corrosive fumes eat metal shelving clean when those rules slip.

Personal Responsibility and Lab Safety

Many accidents come from complacency. One dropped flask after rushing at the end of a late shift can mean a sticky, expensive mess and a worried safety officer. If you take pride in your benchwork, you finish strong: clean tools, clear labels, tight seals. Most importantly, you tell the person on the next shift what you did. This way, nothing sits forgotten, and no one opens a container that’s turned hazardous overnight.

Solutions that Stick

Writing and following a chemical hygiene plan helps. It isn’t just bureaucracy—rules matter. Beware the “it’s just for one night” attitude. Regular audits, real training, visible hazard labels, and functional safety data sheets protect not only your research but also your colleagues. If something looks off or the bottle feels hot, get advice before moving it. Sometimes the best solution is to ask the expert, no matter your own experience level.

Building Good Habits

In my experience, safe chemical storage forms the backbone of sustainable and reliable research. Each smart decision protects the experiment, the researcher, and even the environment. Respect for the risks and respect for the science go together in this line of work. Safe storage isn’t fancy, but it’s completely worth the effort every single day.

Appearance: Substance in the Real World

Spotting 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate on a lab bench sets off a certain curiosity. This compound, often labeled BMIM-TFA, strikes out with its clear, pale yellow liquid form. No powders to collect or crystals to scrape here—what you see is a slightly viscous liquid showing just enough color to stand out among clear solvents, but not enough to mistake it for something hazardous. Picking up the bottle, it feels a little denser than water, and a quick pour reveals how it clings to glass longer than a simple alcohol, showing off that signature viscosity many ionic liquids possess. Scientists and engineers notice these details, using the subtle cues from a material’s appearance and feel to gauge quality or purity before any instrumental analysis.

Melting Point: A Liquid’s Comfort Zone

The melting point tells a lot about a substance’s stability in daily work. BMIM-TFA has a melting point well below most room temperatures, commonly floating around −12°C to −15°C. As someone who has thawed samples or cleaned up spills in a chilly lab, this means the liquid remains “ready-to-go” without constant heating or concern for accidental freezing. Handling doesn’t require any fancy equipment to stay liquid—the kind of practicality that saves time and frustration, especially in busy research or industrial settings where workflow interruptions become costly.

Stability at room temperature isn’t just a handling perk. It runs deeper. A liquid at room temperature cuts down risk during transportation and storage, avoiding pressure buildups or burst bottles you'd get with low-boiling solvents. It’s much less volatile, which means less toxic vapor in the air, and the lab stays a little safer and cleaner, giving peace of mind in routine operations where worker safety must stay front-and-center.

Solubility: The Science of Mixing In

Anyone trying to dissolve solids, extract compounds, or run a reaction knows that a solvent’s solubility matters. BMIM-TFA lines up well with many polar compounds. The trifluoroacetate anion brings some unique flare—similar to what fluorine-containing solvents offer, but with the non-volatile character of ionic liquids. In real use, BMIM-TFA blends easily with water. You pour it in, and it forms a homogeneous solution with barely a stir, which means researchers don’t waste time coaxing it to mix. Many organic substances, and especially biomolecules, dissolve well too, opening the door for work in enzymatic catalysis, separations, and green chemistry routes. It’s less universal for the non-polars, though. Hydrocarbons or traditional greases just won’t play along as easily, which can slow things down or call for a different solvent entirely.

Why These Properties Matter

With its physical traits—liquid at room temperature, easily handled, and eager to mix with polar compounds—BMIM-TFA stays in demand for applications that need something safer and more tailored than flammable organic solvents. In fields like cellulose processing, CO₂ capture, and enzyme-driven synthesis, these fluids help sidestep the risks or inefficiencies of legacy solvents. Environmental and occupational safety guidelines point to benefits in volatility reduction, a point researchers like myself take seriously after years of managing solvent vapors and hazardous waste. Still, it’s not a magic bullet; cost, compatibility, and environmental profile have to factor in too. But these properties keep BMIM-TFA on my shelf and my mind whenever a safer, smarter solution is the aim.