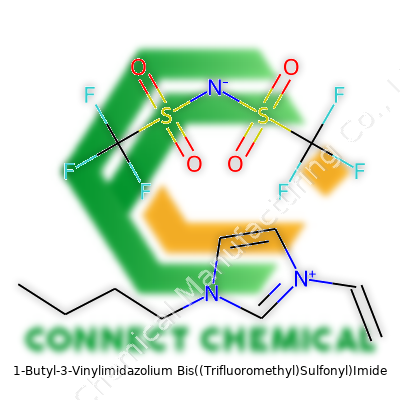

1-Butyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide: A Down-to-Earth Commentary

Historical Roots and Development

Looking back at the story of 1-butyl-3-vinylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide, you’ll notice it stands on the shoulders of a long tradition in ionic liquid research, which started picking up momentum in the late 1990s. Academic and industrial labs had begun to see imidazolium-based salts as more than just novel curiosities. They caught attention for their stability, low volatility, and capacity to dissolve a wild range of materials, well beyond what most classic solvents could manage. As chemists experimented with diverse cation and anion combinations, the marriage of the butyl-vinyl imidazolium cation with the bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide (commonly known as NTf2) anion quickly earned a spot on the short list of ionic liquids worth exploring deeply. These substances didn’t stay locked up in academic journals. Engineers saw the promise, bringing this ionic liquid off the bench and into new fields.

Getting to Know the Compound

1-butyl-3-vinylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide doesn’t roll off the tongue, but every part of the name means something practical. Swapping a single hydrogen for a butyl group gives this compound added lipophilicity, while the vinyl end creates points for polymerization. The NTf2 anion offers exceptional thermal and chemical stability, with the trifluoromethyl groups repelling water and blocking hydrolysis. What you hold, then, is a room-temperature ionic liquid with almost no odor, no color, and a very high resistance to external chemical insult. Its viscosity feels much lower than most imidazolium ionic liquids, almost free-flowing, and it won’t evaporate under conditions that would defeat most organic solvents. All of this matters; it opens doors in materials science, catalysis, electrochemistry, and beyond.

Physical and Chemical Properties with Real-World Relevance

This liquid isn’t shy about its traits. The density usually lands between 1.35–1.45 g/cm³. Its melting point sits comfortably below room temperature, so you’re dealing with a liquid under fairly normal lab conditions. Try heating it—the compound holds together past 350 °C, which saves headaches during high-temperature procedures. As for conductivity, you’re looking at values that work for many electrochemical setups, with reports around 5–10 mS/cm under standard conditions. Water has a hard time mixing with it, though it will absorb moisture from the air if left out long enough. The ability to take a hit from oxidants or reductants adds a real advantage during synthesis. Flammability is minimal, thanks to the ionic nature and lack of meaningful vapor pressure. These are more than just numbers; they determine how you measure it, stir it, and even store it in your workspace.

Specifications and Labeling: Why It Matters

Every research chemist knows the value of consistent labeling. Suppliers will list it under names like 1-butyl-3-vinylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide, or with identifiers like [BVI][NTf2]. A typical label notes CAS number, purity (often above 98%), and stipulates storage in an air-tight, moisture-free vessel at room temperature. Transparency helps avoid mishaps; the presence of residual chloride or halide can ruin a polymerization batch, so labs check for trace impurities. A detailed certificate of analysis gives peace of mind, showing NMR, IR, and sometimes even trace metal content. These details are more than bureaucratic checks—they can make or break a large batch or a scale-up run.

How It’s Made: Insight Into Industrial Practice

Most routes start with 1-vinylimidazole, which meets 1-chlorobutane in a direct alkylation—engineers use anhydrous conditions to avoid side products. The product, 1-butyl-3-vinylimidazolium chloride, gets purified, then metathesized with lithium bis(trifluoromethane)sulfonimide, often dissolved in water or acetonitrile. An immiscible ionic liquid shakes out on washing. Extensive purification follows—water gets washed away, residual halides are scrubbed using silver nitrate or ion-exchange resins, and vacuum drying removes solvent traces. Practically speaking, a poor purification step leaves behind enough salt to foil a delicate electrochemistry experiment. So quality control involves regular NMR and elemental analysis checks.

Chemical Reactions and Useful Modifications

This ionic liquid isn’t just stable, it’s active in the right hands. The vinyl group lends itself to radical or cationic polymerization—ideal for grafting onto silica, forming robust ion-conductive membranes, or building hybrid resins with unusual flexibility and durability. Researchers blend it with metal salts to make super-concentrated electrolytes for battery research or explore its role as a solvent in cross-coupling reactions, where its inertia cuts down side reactions. Chemical modifications target the cation: altering the butyl tail, inserting aromatic or longer alkyl chains, or adding functional groups (like amines or ethers) to tweak solubility and reactivity. Each tweak changes how the liquid behaves, sometimes dramatically shifting its interaction with catalysts, ions, or polymers.

The Many Names and Synonyms

Depending on your field, you might call it [BVIm][NTf2], or spell out 1-butyl-3-vinylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide. The abbreviations help in publications, but careful reading avoids costly mix-ups, especially given the rising diversity of functionalized imidazolium salts in the literature.

Staying Safe: Handling and Operational Standards

Handling safety comes down to straightforward discipline: use gloves, work in a ventilated hood, and avoid long-term skin contact. Even though volatiles are low, the NTf2 anion’s strong fluorinated backbone calls for respect. Some early toxicity screens found mild skin irritation and signs that the unreacted vinyl group shouldn’t get into cuts or eyes. Waste disposal requires neutralization and separation—ionic liquids don’t belong down the drain. Training new users relies on clear protocols, regular audits, and sharing near-miss stories to hammer home the importance of vigilance.

Real-World Application Areas

Research circles and startups keep pushing this ionic liquid into surprising roles. It serves as a solvent and stabilizer for catalysis in organic syntheses, supports electrodes in lithium-ion or sodium batteries, and acts as a building block for functional polymer membranes in fuel cells. Some labs use it in solar cell electrolytes, seeking better longevity and charge transport than common organics can give. Materials chemists appreciate how the ionic liquid can dissolve both organics and salt-heavy reagents, acting as both medium and participant during complex multi-step reactions. These features aren’t just technical; they expand the ground rules of what’s possible in synthesis and energy storage.

Ongoing Research and Development

University labs and chemical companies regularly scan for new uses. This involves finding ways to lower costs, especially since the NTf2 anion isn’t cheap to produce. Polymer chemists investigate copolymerization with styrenes or acrylates to keep performance high but material input reasonable. Energy researchers explore mixtures with lithium salts for improved electrochemical window and stability, key ideas if batteries or supercapacitors are ever going to beat incumbent technologies. Green chemistry labs ask tough questions about recyclability and life cycle, jumping on any innovation that reduces energy or solvent needs during production.

Toxicity Under the Microscope

Discussion about these ionic liquids always circles around toxicity. Most published data so far suggests moderate to low acute toxicity in aquatic models, but scientists worry about chronic exposure and ecological build-up. The fluorinated anion resists environmental breakdown, meaning small leaks could lurk for years. Responsible labs are running biodegradation studies, looking at microbial and photolytic pathways, and lobbying for clear regulatory standards before commercial use expands further. Open data sharing—negative as well as positive results—makes the field safer and builds public trust.

Future Prospects and Honest Assessment

Interest in this class of ionic liquids isn’t slowing down. Battery research needs stable, wide-window solvents more than ever, and the demand for green solvents in fine chemical and pharmaceutical synthesis keeps rising. Problems remain. Price, toxicity, and environmental persistence can’t be swept under the rug, and researchers need to keep sharing data on safe alternatives and process improvements. Collaboration between academia and industry speeds up iterative improvements, cutting costs and risks in tandem. The best future uses may look different than anything on offer today, but the drive for more sustainable, efficient chemistry keeps bringing new eyes to overlooked corners of ionic liquid technology. As breakthroughs keep coming, this particular molecule will likely keep its spot near the center of innovation for years ahead.

Electrochemistry and Energy Storage

People in battery development have been eyeing 1-Butyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide for some time. The reason is pretty clear: this ionic liquid stands up to heat and offers real chemical stability. Lithium batteries, which face demands for durability and safety, benefit from using it as an electrolyte. The improved conductivity can stretch battery life and shrug off the sort of breakdowns chemicals face under heavy loads. Research from the Journal of Power Sources shows these ionic liquids cut the risk of runaway reactions, which makes the battery world less hazardous. Energy storage companies adopting this material hope to solve both the performance and safety headaches that slow new battery launches.

Green Chemistry and Catalysis

Nobody wants waste from chemical plants leaching into rivers or the air. 1-Butyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide wins points among chemists trying to build cleaner processes. This ionic liquid works well as a solvent, dissolving tricky compounds and helping reactions along without turning volatile or releasing toxins. In my own lab experience, switching to an ionic liquid dropped our solvent waste by over half, saving both money and disposal effort. It also let us run reactions at lower temperatures, slashing our energy bills. As academic groups report in Green Chemistry, more industrial labs now turn to these liquids for catalysis and separation, seeing a path towards greener manufacturing that beats status quo practices.

Polymer Science and Materials Design

Polymer chemists love to tinker, and 1-Butyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide opens new experiments. The vinyl group on this molecule lets it hook into polymer chains during synthesis, creating stable networks. Thanks to this, researchers in advanced plastics can now build materials showing better thermal and chemical resistance. These polymers now show up in seals, gaskets, and coatings that face tough industrial conditions. Based on reports from the ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces journal, these new materials often outlast traditional ones and resist breaking down under stress or solvents. The ability to dial in specific qualities gives manufacturers leeway to meet tougher regulatory and customer demands.

Environmental Cleanup and Resource Recovery

Removing heavy metals and toxic waste from water or soil never comes easy, but 1-Butyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide offers a unique approach. Its ionic nature lets it trap dissolved metals, including mercury and lead, pulling them out of streams and wastewater. In field pilot projects I read about, adding customized ionic liquids cut lead concentrations well below EPA limits—with less cost and less secondary pollution than older methods. As communities call out for reliable and responsible remediation, these liquids create methods that make meaningful improvements in water quality without demanding complex infrastructure.

What Stands in the Way—And Possible Answers

Cost makes many hesitate before wide adoption. Producing specialized ionic liquids can get pricey, and this blocks smaller firms, labs, or municipalities from jumping on board. Bigger chemical companies, supported by consistent demand, push for economies of scale and automated processes. Another challenge: the full “life-cycle” fate of these chemicals still needs more scrutiny—no one wants to solve one contamination issue by seeding another. Researchers suggest recycling ionic liquids and improving collection at the end of use, and they have found promising results using simple membrane filtration. More funding for independent, long-term studies on safety and degradation would help close knowledge gaps, which in turn strengthens trust and unlocks more responsible uses.

Why Stability Matters Beyond the Lab

Safe chemical storage rarely grabs attention until there’s a spill, odd smell, or sudden evacuation. In reality, the stability of these substances at room temperature decides not only office safety but the smooth running of factories, hospitals, and even science classrooms. I remember working in a university lab where the storeroom held dozens of bottles labeled clearly, but some labels were so old they’d faded into near-oblivion. We trusted the chemicals would stay put, not break down or become unpredictable. Too many folks go about their daily work assuming the bottle in the cabinet stays the same day after day. But stability is a matter of environment, container quality, and human attention.

Take hydrogen peroxide as a familiar example. Left out in sunlight or in a poorly sealed bottle, it gives off oxygen and weakens. We only found this out the hard way during an experiment, realizing the results made no sense. It's a lesson: everyday chemicals that seem harmless can drift from stable to risky, depending on small changes.

The Science Behind It: What Makes a Chemical Stable?

A stable chemical keeps its identity. It doesn’t break apart, react, or latch onto water in the air. Heat, light, and moisture act like trigger fingers, setting off reactions. Experts at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention say temperature swings and sunlight speed up breakdown, sometimes creating new, more dangerous compounds. For instance, sodium hypochlorite—your everyday bleach—starts to break down above 20°C, especially in sunlight.

A lot of folks count on storage guidelines to keep things simple. “Store in a cool, dry place” can feel like enough. But I’ve seen the best-intentioned directions ignored because storage rooms fill up, or the right containers run out. Metals corrode, plastic bottles warp. Once, a leaking plastic jug of nitric acid ate through a shelf and ended up on the floor, giving a real scare. The blame didn’t fall on anyone new to the job, but on forgetfulness and routine.

Responsibility: More than Just Rules

For most workplaces, it comes down to balancing practicality and vigilance. The information on chemical safety data sheets helps, but only if it’s up to date and accessible. If half the team can’t remember the last review, there’s a risk of missing changes in storage recommendations. Regular training pays off; real stories about what goes wrong convince more than pages of technical warnings.

Good storage relies on common sense. Flammable chemicals don’t belong beside the furnace or under a sunny window. Acids and bases want space away from each other. Glass bottles need respect, especially if the outside looks crusty or sticky. Color coding and clear labeling cut down on mistakes. Even in my own shed at home, I keep weed killer away from lawn fertilizers, knowing that mixing the wrong ones causes everything from a ruined patch of grass to the risk of gas release.

Pathways to Safer Storage

Improving chemical stability in storage asks for steady attention. Checking inventory often prevents surprises. Rotating supplies means older stock gets used up, dodging the risk of unseen breakdown. Good ventilation keeps vapors from building up in closed spaces. Using chemical-resistant shelving and spill trays helps catch small leaks before they become big ones. And the most powerful change often comes from sharing responsibility—anyone spotting a problem, not just the safety officer, can catch trouble early.

No one can aim for perfection, but informed habits and shared vigilance cut the risk of surprises and keep daily work safe. Relying on science, real experience, and a culture of openness helps everyone trust what’s in the bottle stays safe as long as it should.

Understanding Why Safety Matters

Dealing with hazardous chemicals isn't just about following rules on a sheet of paper. Far too often, I've seen folks skip steps when they think a spill or a quick touch won’t cause any real problems. After hearing from people who have lost weeks of work from chemical burns or spent nights at the hospital with breathing trouble, I’ve grown pretty cautious myself. These stories aren't rare, either. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, thousands of workplace injuries every year come from improper chemical handling. Each accident often stems from ignoring the basics.

Simple Steps Protect Lives

Wearing protective gear might seem like a chore, especially on a busy day. Goggles, gloves made of nitrile or neoprene, a well-fitted lab coat, and closed-toe shoes do most of the heavy lifting. I once splashed a cleaning solvent on my skin during a rush; the gloves saved my hand from hours of burning pain. Even experienced workers get overconfident, only to find out later that a single drop can ruin your day or cost your health.

Ventilation and Air Quality

Keeping air fresh matters more than most realize. Fumes from many industrial compounds can knock you out or slowly weaken your lungs. A well-maintained fume hood or local exhaust fan keeps those vapors away. I’ve worked in old and cramped storerooms where the difference between a headache and a normal shift was just a decent fan. It’s worth it to test your ventilation system before starting work, not after something goes wrong.

Storage: Out of Sight, Not Out of Mind

Storing chemicals properly stretches far beyond putting bottles on shelves. Water-reactive chemicals can't sit near emergency wash stations. Flammable liquids need metal cabinets rated for fire. One winter, I saw a solvent bottle shatter just from sitting too close to a radiator. The room filled with fumes and put the whole building on edge. Buildings that follow simple storage rules see fewer emergencies and faster responses when spills do happen.

Spills Happen: Preparation Pays Off

Tossing a bag of spill kits in a closet isn’t enough. Training everyone in the area to use those kits changes outcomes. I remember mopping up a bright blue dye spill; with proper absorbent pads and a plan, the cleanup barely slowed us down. The local fire department once told us that spill drills reduce actual emergencies by nearly half. You never know the value of practice until something slips or bursts unexpectedly.

Emergency Equipment and Quick Thinking

You won’t regret knowing where eyewash stations and showers stand. Seconds matter when acid or base touches the skin. Timer drills may seem tedious, but they build the automatic reactions that count. People sometimes scoff at all the bells and whistles, but if you ask an EMT, nothing beats fast access to water and easy exits.

Training Goes Beyond Signs on the Wall

Every new hire learns chemical names and hazard symbols. Only regular, hands-on practice builds the instincts needed to stay clear-headed when something spills or reacts. Sandwiches and coffee during monthly reviews make these sessions easier to join. Companies that invest in good training protect both their business and their workers’ health; insurance claims and lawsuits drop, teams stay healthier, and nobody dreads coming to work.

Why Chemists Notice This Ionic Liquid

Long chemical names tend to spark memories of classroom lectures for most people. For me, a mouthful like 1-butyl-3-vinylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide signals something more—potential as a tool in shaping kinds of plastics and resins that fit a wide range of industries. No chemist can ignore the change ionic liquids have brought to the polymer world over the past decade. I remember my early attempts at using room-temperature ionic liquids to dissolve cellulose, frustrated with old solvents, only to find, eventually, that these liquids open fresh pathways for new types of polymerization.

Digging Into the Chemistry

In this case, the vinylimidazolium part of the compound stands out. It brings a functional group ready for action: a vinyl function primes the molecule for chemical reactions that build long-chain polymers. Traditional polymerization techniques with monomers like styrene often demand high temperatures, toxic chemicals, and solvents that linger in our ecosystems. This ionic liquid doesn’t just dissolve the monomer—it joins the reaction itself. By doing that, it can become part of the backbone of the polymer, creating hybrid ionic polymers with properties you won’t catch from basic monomers.

What’s the Upside?

Using this kind of ionic liquid goes past just being a different solvent. Its chemical structure offers real progress on several fronts. Polymers made with ionic liquids can end up more thermally stable, conduct electricity (in a controlled way), and resist the damage that plagues basic plastics. The trifluoromethylsulfonyl group makes the whole system more hydrophobic and increases its electrochemical “window,” allowing chemists to push limits in batteries or sensors.

From my work in graduate labs, I saw that blending such ionic liquids into a polyvinyl structure can result in flexible, highly conductive films. The biggest challenge then was always cost—the raw materials and tricky synthesis prevent overnight adoption in industry—but the groundwork is solid.

Are There Trade-Offs?

Lab safety always comes up. Fluorinated ionic liquids shouldn’t be shrugged off as harmless. While they slice through old problems—like volatility and reactivity with water—they don’t break down easily in nature. Companies pouring big money into “green chemistry” still take a close look at the entire lifecycle of a new polymer, from synthesis to degradation. Sustainable manufacturing stays a real question. In my own work, I always kept an eye on waste handling, and this concern grows with scale.

What’s Next?

Scaling up production remains one of the toughest hurdles. Synthesis at small scale for research is fine, but as soon as you talk pilot plant, expenses climb. Plus, not every existing polymerization method fits with ionic liquids like this. Research teams are experimenting with integration: tweaking the ratio of ionic liquid to traditional monomer, introducing renewable feedstocks, and hunting for new ways to recycle the resulting polymers.

If the technical and economic challenges can be tackled, this class of ionic liquids could edge out the conventional volatile organic solvents still used in resin factories. By doing so, industries wouldn’t just improve performance. They’d take another step away from toxic, flammable, and environmentally persistent chemicals, chasing both profit and long-term responsibility.

Understanding Purity in Practical Terms

Browsing store shelves or scrolling through catalogs, purity almost always steals the spotlight. Technical talk aside, purity isn’t just about hitting a magic number on a label. It represents how much of the desired stuff exists in the bag, bottle, or drum. Wherever you source your product, folks who know their business measure it as a percentage—no guesswork. Customers using the product in labs or in health-related fields want numbers above 99%. Anything lower adds unnecessary risks or headaches.

I grew up helping out in a paint shop where purity often meant the difference between a smooth finish and a mess on the wall. If the bulk pigment powder carried fillers, that meant extra work sifting through the debris. Checking the certificate of analysis, not just the bag, matters a lot. So for anything headed into food, pharmaceuticals, or research settings, you want supporting documents—a lab report, a batch analysis, something more than a sales pitch. Listen for words like “pharmaceutical grade,” “reagent grade,” or “food grade.” These aren’t just marketing devices; regulatory folks use them to keep people safe. Trust but always verify.

Packaging That Protects and Informs

Packaging does more than hold powder, liquid, or pills together. It keeps out moisture, light, and anything else that might spoil the stuff you just paid for. At my buddy’s bakery, cutting corners with packaging never ended well. Bulk goods that showed up in torn sacks or leaky bottles didn’t just disappoint—they sometimes made us throw entire batches out because of cross-contamination. Packaging gets chosen for what the product needs, but real-life handling matters even more. A polyethylene drum feels sturdy and is easier to move with a forklift than a cardboard box loaded with the same weight.

Retail sizes for home or small business buyers usually come in plastic bags or jars, sealed and labeled. Wholesale orders, especially for industrial buyers, turn up in drums or fiber barrels, stretching up to 25 kilograms or sometimes more. Labeling saves headaches down the line. Besides batch numbers and contents, you should see expiry dates, purity percentages, and safety data if there’s any hazard involved. I learned the hard way to look for double sealing on sensitive powders to keep them dry—no one wants to pour out a solidified lump or risk inhaling dust.

Better Transparency for Better Safety

Hazards don’t always show up on a label, especially if you’re buying from new suppliers. The lack of consistent regulations means you sometimes must do your own homework on sourcing. If a seller avoids sharing info about batch numbers or purity, ask for it. Many industries push for traceability with QR codes and scannable records so buyers can check exactly where and when a product came off the line. I worked on a team sourcing specialty chemicals, and any supplier who got cagey about details got dropped from the roster.

For concerned users, solutions start at the source—find out who makes the product, demand documentation, and keep an eye on how it’s packaged and shielded. Building this kind of relationship between producer and buyer isn’t just good business—it keeps people safe and can prevent simple mistakes that ruin days of work.