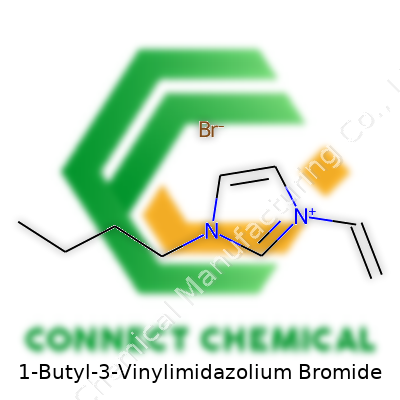

1-Butyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide: Chemistry, Use, and Future

Historical Development

The rise of ionic liquids began to transform chemistry in the latter half of the twentieth century. 1-Butyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide stands as one of those tailor-made molecules that caught researchers’ attention. Early on, scientists carried a hope that non-volatile, thermally stable liquids would open fresh avenues in green chemistry and electrochemical applications. By the late 1990s, imidazolium-based ionic liquids hit academic journals with data showing less risk to the atmosphere and much greater design flexibility when compared to typical solvents. The butyl-vinyl side chains gave further room for reactivity, making this molecule more than just a solvent — it became a reactive tool in its own right.

Product Overview

1-Butyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide appears as a pale, viscous liquid or sometimes a low-melting crystalline solid, depending on the purity and temperature. Manufacturers focus on consistent quality because this compound finds its way into research labs, battery development, catalyst work, and even pilot manufacturing projects. Chemical suppliers often ship the product in airtight, light-protected bottles, warning users about its moisture sensitivity. This single molecule holds a unique position, with roots in both classic salt chemistry and modern polymer science.

Physical & Chemical Properties

One key feature is its low vapor pressure, which nearly eliminates loss to the air in open labs. The melting point sits close to room temperature and shifts with water content. At modest heating, the liquid phase sticks around and offers high ionic conductivity. Water mixes in at a slow but steady pace, often requiring careful storage. Unlike many other imidazolium salts, its vinyl substituent turns out highly reactive and stays available for further reactions. The octanol-water partition coefficient rests low, and that helps reduce bioaccumulation risk in the environment. Stability under both acidic and basic conditions builds confidence for anyone pushing into multistep syntheses.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Quality control teams typically check each lot for purity (>98%), moisture content (below 0.5%), color, and melting point. Suppliers attach GHS-compliant labels laying out the structure, main hazards, and the recommended personal protective equipment. Chemical compatibility information rests in the safety data, crucial because this material reacts fast with nucleophiles during polymerizations. Researchers pay attention to lot numbers and batch tracking, knowing slight impurities can skew long-term experiments. Most technical data sheets mention density (about 1.25 g/cm³), a conductivity in the tens of millisiemens per centimeter, and a refractive index to guide high-purity handling.

Preparation Method

The synthesis walks down well-trodden territory of imidazolium salt chemistry. Typically, 1-vinylimidazole gets alkylated with 1-bromobutane under controlled heating. After the reaction, the mixture cools and produces a dense, oily layer separating from unreacted materials. Repeated extractions and washes with ethyl acetate or ether remove organic leftovers. Sometimes, cold recrystallization or vacuum drying tightens up the purity, especially if the product must sit on a shelf before further use. Chemists keep a close eye on each step, since both product and byproducts become sticky at times. Good ventilation, gloves, and sometimes a drybox cut down on exposure risk.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The vinyl group lets this salt act as a building block for radical polymerization, snapping together into long conductive chains. Cross-linking transforms the ionic liquid into a tough gel or elastomer, which holds appeal for battery membranes and separation sheets. On the cation piece, the imidazolium ring brings tunable electrochemical properties, making it flexible for redox chemistry and organometallic catalysis. Halide exchange and metathesis reactions give access to related salts, letting scientists tweak properties as needed. Researchers keep pushing reactions further, testing hydrophobic anions, co-polymer blends, and hybrid materials to solve real-world challenges.

Synonyms & Product Names

You can spot this material under several product names. 1-Butyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide stands as the IUPAC-driven name, but chemical catalogs also list [BVIm]Br, N-butyl-N′-vinyl-imidazolium bromide, and at times, abbreviations like BvimBr. Brand names sometimes tack on purity or polymer grade, but the backbone remains the same. Lab staff must keep an eye on catalog numbers, especially when ordering across multiple suppliers.

Safety & Operational Standards

Most people in the field recognize that even “green” solvents deserve care. This liquid irritates skin and eyes, so labs mandate gloves and long sleeves during handling. Chronic exposure studies remain limited, which means nobody can brush off basic precautions. Staff avoid heating the compound in open air, since thermal breakdown makes volatile organics and hydrogen bromide — both hazardous. Fume hoods, grounded transfer lines, and proper waste collection keep small mishaps from turning into reportable incidents. Lab managers lock this material away from food and drink, and new students get a safety briefing before their first experiment. Emergency showers and eyewash stations stay close by, not just for compliance but for practical protection against splashes.

Application Area

Chemical engineers find plenty of use for 1-Butyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide in the hunt for high-performance electrolytes for lithium and sodium batteries. The ionic nature means rapid ion mobility and good temperature resilience, both prized in battery design. In the world of polymer chemistry, chemists exploit the vinyl group to make polyelectrolytes that turn up in selective ion-exchange membranes. Environmental researchers work with it to dissolve tough biomass for green chemistry projects aimed at reducing chemical waste. Catalysis provides another home, where the ionic liquid serves both as a mild solvent and as an active component in transition metal reactions. Electroplating, organic synthesis, and gas separation round out the main uses most often seen in the literature.

Research & Development

In research, this molecule shows up almost everywhere ionic liquids break new ground. Scientists test variant anion combinations, blending with other ionic liquids and polymers to stretch the envelope on conductivity and thermal range. Electrospinning and 3D printing projects push into new scaffolds for tissue engineering and chemical sensors. Each new derivative offers a possibility for selective ion transport, aiming straight at problems in energy storage and environmental cleanup. Scale-up teams wrestle with process optimization, since pilot plant yield and purity make all the difference between promising research and commercial reality. University groups and chemical manufacturers both lean on high-throughput screening and data mining to predict next steps and avoid costly dead-ends.

Toxicity Research

Toxicity studies on 1-Butyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide remain limited, but what’s been published points to moderate risk in aquatic environments if not handled properly. Unlike old chlorinated solvents, this ionic liquid tends not to evaporate or bioaccumulate easily, which counts in its favor. Short-term exposure shows skin and respiratory irritation in rodents, and chronic study data are still sparse. Regulators urge strict containment in lab settings until broader screening provides reassurance. Regular monitoring of waste streams and workplace air keeps everyone safer, and staying updated on new toxicological reports goes a long way to building a responsible culture.

Future Prospects

The future of 1-Butyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide looks promising, riding on the back of the ongoing green chemistry movement and the race for better battery technology. Industry wants cleaner, safer alternatives to volatile organic compounds, and these ionic liquids provide a custom-fit approach. Research continues to unlock new roles as catalysts, reaction media, and functional materials for sensors, membranes, and smart coatings. Automation ties in with sustainable manufacturing, seeking scalable and cost-effective processes. As new safety and environmental data roll in, guidelines will follow to shape its large-scale adoption. The pathway for growth stays tied to careful research, transparent reporting, and honest risk assessment at every level.

Chemistry's Modern-Day Workhorse

Walk through any modern chemistry lab and there's a good chance you'll find ionic liquids tucked away among the glassware and reagents. Among them, 1-Butyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide stands out as a kind of multi-tool, quietly changing the way researchers approach problems in synthesis, catalysis, and material science.

Green Chemistry Moves Forward

Anyone who has spent time handling volatile solvents knows the headache they bring: fumes, fire risk, complicated waste. This compound offers a promising shift. Thanks to its unique structure, it dissolves a range of compounds without giving off hazardous vapors. I remember the first time swapping out a batch of acetonitrile for an ionic liquid—less eye-watering, less worry, better results. Labs aiming to clean up their environmental footprint often pick up 1-Butyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide to cut down on waste and make their workspaces safer.

Supporting Polymer Science

Materials science teams have latched onto this ionic liquid for tough jobs—especially where traditional polymerization struggles. Its vinyl group opens doors in copolymerization, where it bonds with other vinyl monomers to create new polymer structures. This leads to membranes and films for fuel cells or water treatment systems, projects that demand reliability and chemical resistance. The experience of seeing a failed membrane replaced with a version sustained by an ionic liquid’s backbone speaks volumes about its value in the research and industrial worlds.

Electrochemical Solutions

Batteries, supercapacitors, flexible electronics—these devices lean on advances in electrolytes to push their limits. 1-Butyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide works as a stable, ion-conductive medium, making charge transfer smoother. I’ve seen my share of failed battery tests. Electrolyte breakdown or poor ion mobility can end months of work in minutes. Using ionic liquids helps extend device lifespans, and the performance bumps aren’t just numbers—they give real products more punch in the field.

Catalysis and Extraction

The chemical industry is always looking for ways to run faster, cleaner reactions. Catalysis in ionic liquids like this bromide often triggers higher selectivity and better efficiency. I spoke with a colleague who shifted a multi-step pharmaceutical reaction into an ionic liquid—yield ticked up, workup hassles faded. Such tales echo across the industry, especially in greener processes for making drugs and specialty chemicals.

Tackling the Roadblocks

No compound solves everything. The cost of ionic liquids and tricky recycling remain real challenges. Large processes still rely on older solvents, waiting for further price drops and better recovery methods. Solvents like 1-Butyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide push progress, but more scale-up studies are key.

Forward Steps

Some research groups focus on cutting the price through custom synthesis routes. Industry and academia both keep looking for greener and cheaper alternatives, often tweaking the structure for each new application. Renewable starting materials might unlock larger-scale use, shrinking the sustainability gap.

A Tool for Today and Tomorrow

It’s easy to get swept up in new technology hype, but in the hands of scientists focused on real-world impact, 1-Butyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide proves its worth. Whether cleaning up chemistry or driving the next battery leap, this ionic liquid continues to earn its place in the lab and beyond.

The Value of Chemical Stability in Daily Work

Anyone who’s spent time in a laboratory knows that chemical stability shapes everything—from experiment outcomes to health and safety in the workplace. The stability of a compound says a lot about its shelf life, effectiveness, and safety. It often boils down to the structure of the molecule itself. Some molecules hold together with ironclad bonds, while others start breaking down the minute they encounter moisture or light.

What Makes a Compound Stable—or Not

A stable compound resists changing form, even as time passes or conditions shift. Many materials prefer cool, dry spaces since humidity and high temperatures boost reaction rates. Oxygen in the air can kickstart oxidation, breaking apart sensitive structures—think of iron rusting, only at the molecular level.

Light plays its part, too. Ultraviolet rays can punch enough energy into bonds to split them apart. Certain pharmaceuticals lose potency if stored under bright conditions. Even common substances, such as hydrogen peroxide, break down into water and oxygen under the wrong lighting.

Why Storage Conditions Matter in the Real World

I once left a bottle of reagents on a bright windowsill at home, figuring a few hours wouldn’t hurt. Next day, what should have been a clear solution had turned cloudy. That small lapse underlined the simple rule: most chemicals don’t forgive careless storage.

For everyday chemicals, even a misplaced cap or forgotten label raises real risks. Even experienced hands read the safety data sheet (SDS) before opening a new container. The SDS usually spells out just how long to keep the compound, whether to avoid plastic or metal, and what environment prevents dangerous reactions.

Common Storage Mistakes and Fixes

Lab fridges get crowded. Sometimes acids end up way too close to organics. Once, a bottle of strong base wound up next to flammables, raising the chance for a hazardous reaction if leaks happened. Simple habits—like checking labels, keeping incompatible groups on separate shelves, and logging bottle openings—keep disasters at bay.

Even packaging matters more than many realize. Dark-glass bottles protect against stray light. Tight caps and desiccants cut down on moisture, while flame-resistant cabinets shield against fire risks. In industrial settings, automatic systems track temperature and humidity, sending alerts if things move outside safe ranges.

Balancing Access and Safety

Experienced staff balance safety rules with daily routines. Some hazardous items need double containment. Rarely used compounds get stashed farther from busy work areas. In my first research job, mentors always made a point of keeping up-to-date with regulations and best practices—extra effort that paid off when audits rolled around.

Room for Practical Improvements

No system stays perfect forever. Routine inspection prevents small problems from turning into big ones. Investing in temperature monitors and better labeling pays for itself by avoiding ruined stock. Training sessions help staff spot changes in appearance, odor, or texture—early signs of instability. By keeping up with new research and manufacturer updates, workplaces can adjust storage guidelines, reducing waste and risk over time.

Making careful choices about storage, paying attention to chemical signals, and using resources like the SDS keep both people and compounds in their best shape. Proper stability and smart storage practices help everyone—from students to seasoned chemists—work with confidence.

Understanding the Chemical Behind the Name

1-Butyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide pops up in research labs as an ionic liquid, often chosen for its unusual mix of properties—non-flammability, good conductivity, and impressive solvating power. It goes by less catchy names, but its most important features stem from an imidazolium core hooked up with butyl and vinyl arms. In chemistry circles, this substance stirs both promise and caution.

Looking at the Hazards

People working in the lab know safety data sheets are not just a formality. The makers flag 1-butyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide as an irritant for skin and eyes, with inhalation risks if powders float into the air. I’ve seen students skip the gloves with “benign” chemicals and regret it later. Even compounds that don’t trigger immediate symptoms can build up trouble over time. Ionic liquids like this one often slip under the “green” chemistry label, but that doesn’t mean they are harmless for people or the planet.

Some data points show that imidazolium-based ionic liquids can mess with aquatic life if they escape the lab sink, even at fairly low concentrations. As their popularity rises, so do concerns about toxicity to micro-organisms and the persistence in water. The vinyl group gives this compound extra reactivity, which means it might add to risks in ways typical salts do not. I’ve watched a growing number of chemists argue for closed-loop systems and careful waste collection, since these substances can resist breakdown by bacteria.

Protecting Yourself and the Environment

A responsible approach starts simple: keep personal protection strong. Gloves, splash goggles, lab coats—never an afterthought. Avoid open beakers or bulk handling that can stir up dust. Run reactions in a fume hood, and use tightly sealed bottles. Most colleagues know one spill can trigger a lot of paperwork, if not worse. Training isn’t just for new interns—refresher sessions save headaches and sometimes much more.

Ventilation matters. Ionic liquids don’t usually evaporate at room temperature, but mishandling can result in aerosols or splashes. Clean tools thoroughly, and always label waste for hazardous pickup. No one wants to clean out a drain trap months later and meet chemicals that don’t belong in the water stream—or the food web.

Weighing the Benefits and Responsible Solutions

Cutting corners raises long-term costs; regulations already press for better documentation and disposal methods. Labs can invest in greener alternatives or search for less persistent analogues. Regular review of safety protocols works better than any rulebook left on a shelf. Seek out up-to-date, peer-reviewed toxicology studies before any scale-up. If your group is switching to ionic liquids for “green chemistry,” keep the full life cycle in mind.

Safety demands culture, not just compliance. My years in research have taught me—overconfidence multiplies risk. Even chemicals with trendy labels deserve measured respect. Factoring in environmental release, acute exposures, and chronic hazards, 1-butyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide shouldn’t be underestimated.

Understanding the Compound

1-Butyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide isn’t just another name from the long list of ionic liquids. This compound brings some unique features to the lab bench. Its structure balances a butyl chain, a vinyl group, and the imidazolium core. Each part shapes how it behaves, whether we talk about solubility or its interactions with other molecules. My work with ionic liquids in graduate school meant experimenting with stability and reactivity, and I saw quickly how a small tweak—something like a vinyl group—can transform not just the molecule, but the chemistry it makes possible.

Why Vinyl Groups Matter

The vinyl group here is important. Vinyl groups attach themselves to polymer chains—this is classic chemistry. In normal chain-growth polymerization, a free radical targets a double bond. The vinyl group offers one, so 1-butyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide can take part in reactions like free radical polymerization. We’re not just theorizing; peer-reviewed studies highlight how vinyl-imidazolium salts become building blocks for new polymers, with added ionic character and thermal stability.

Environmental and Practical Benefits

Ionic liquids like this one gained popularity because they don’t evaporate like regular organic solvents. In my experience, nobody misses the headaches from acrid fumes. Using ionic liquids cuts down on volatile organic compound emissions, which keeps labs safer and helps research groups meet environmental standards. On top of that, these compounds can help recycle unreacted monomers, since many polymers sink out and the ionic liquid remains reusable. Sustainability isn’t a buzzword in the context of ionic liquids—it’s a benefit you can see in lower solvent waste and cleaner workspaces.

Polymerization Successes and Possibilities

What happens in real research? Teams working with 1-butyl-3-vinylimidazolium salts set off vinyl polymerizations to produce ionic polymers. These materials show promise in applications from ion-exchange membranes to batteries. When I trialed similar ionic monomers, I noticed much greater conductivity and sometimes higher resistance to harsh chemicals than with classic polymers. The presence of an imidazolium ion in the polymer backbone nudges the material toward electrochemical uses.

But not every lab jumps on board immediately. These salts can be tricky to make at scale. They cost more than simple vinyl monomers. I remember running into supply headaches; a shipment delay from a specialty supplier could halt everything. That reality highlights a recurring challenge in polymer science: technical promise doesn’t always translate straight to practical adoption. Academic labs can test ideas quickly, but industry needs reliability and lower costs to switch over.

Improving the Landscape

To open the door wider for 1-butyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide-based polymers, more efficient and greener production techniques would help. Collaborations between synthetic chemists and chemical engineers could bring down costs. Reliable routes for recycling or reusing spent ionic liquids would also move things along. Academic research highlights the value, but partnerships with industry are crucial for scaling and testing in real-world devices. That's where government funding or incentives for green chemistry sometimes make all the difference—especially if backed by strong data on lab safety and environmental impact.

Why Purity Levels Matter

Years spent working on projects where chemicals play a key role taught me one important lesson: purity isn’t just a number on a spec sheet. It speaks to trust, reliability, and performance. Whether lab technicians aim for breakthrough research or manufacturers ramp up large-scale production, small mistakes in composition can derail results. Purity is the shield that guards against contaminants, keeping reactions predictable and finished products trustworthy. For instance, pharmaceutical-grade material often aims for a purity rate above 99%, meeting the standards demanded by regulators. Even small variances can lead to failed tests or ineffective medicines. High purity grade doesn’t simply tick a regulatory box—it protects a company’s reputation and ensures the end-user’s safety.

Common Purity Grades in the Market

Broadly, companies provide several grades, catering to different uses. Reagent grade, analytical grade, and technical grade each serve a purpose. Reagent and analytical grades clock in at the top of the scale, generally above 98%. Technical grade might fall lower, often under 95%, yet it still fills crucial roles where ultra-high purity won’t alter outcomes, like in certain industrial processes.

During my stint in a water treatment startup, technical grade chemicals made economic sense for initial tests. But reaching pilot-stage, we switched to higher-purity inputs because results had to meet tighter safety and efficiency metrics. Anyone sourcing materials should pay attention to these differences—cutting corners rarely pays off for critical applications.

Packaging Sizes: More Than Just a Box

Packaging selection impacts workflow efficiency, shipping safety, and cost control. For research and small batch development, suppliers offer small bottles or containers—often starting at 100 grams or 500 milliliters. Labs working with multiple trials appreciate these smaller formats, keeping waste minimal and contamination risks low.

Scale up to industry, and options grow. Companies use drums, bags, and even bulk tankers for sizeable orders. A 25-kilogram bag or 200-liter drum suits manufacturing plants demanding steady supply. My own days working in materials procurement taught me to always double-check packaging seals, since one faulty drum could spoil an entire production run.

Flexible packaging sizes help match purchase to need. Too little, and frequent orders eat time and money. Too much, and storage becomes a problem—especially for sensitive compounds.

What Good Suppliers Offer

Reliable vendors focus on transparency. They publish purity data backed by third-party testing and ship with clearly labeled packaging, showing batch numbers and expiry dates. Some go a step further by including certificates of analysis, a practice I came to appreciate after one supplier’s mislabeling nearly sent our team back a month.

One solution for buyers concerned about quality: always ask for documentation before placing a large order. Open communication with the supplier smooths the path—companies willing to walk through their specs tend to stand behind their products. In regulated sectors, smart buyers work only with certified sources, reducing the risk of compliance or safety issues.

Matching Choice to Need

Every decision around purity and packaging ties back to what the material will actually do. A teacher ordering for a school science lab doesn’t face the same risks as a pharmaceutical plant manager. Experience shows decisions made up front—choosing the right grade and pack size—save far more money and trouble in the long run than trying to fix a problem once it’s arrived in the warehouse.