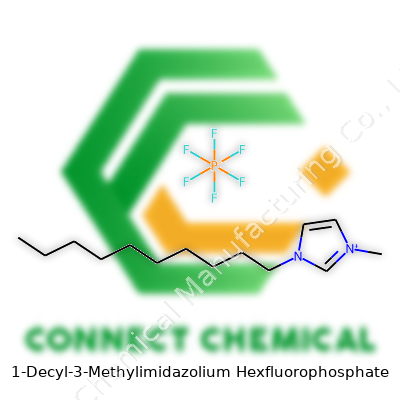

1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hexafluorophosphate: A Deep Dive

Historical Development

Organic salts like 1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hexafluorophosphate (often abbreviated as [DMIM][PF6]) first drew attention during the late twentieth century, right when chemists looked for alternatives to conventional solvents. Looking back, the introduction of ionic liquids marked a real shift in lab practice. These substances get praised for their low volatility, uncommon stability, and tuneable properties. [DMIM][PF6] grew popular along with a whole family of imidazolium-based ionic liquids, gaining traction as researchers left traditional, volatile organic solvents behind. Discovery and testing of ionic liquids have grown hand in hand with advances in green chemistry, as scientists lean into making processes that don’t damage the atmosphere and water. Pioneering journals in the late 1990s documented these transitions, with labs in Europe, Asia, and North America all joining the chase for improved solvents.

Product Overview

1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hexafluorophosphate belongs to the imidazolium ionic liquid family. It blends a decyl side chain with a methyl group on the imidazole ring, joined to the hexafluorophosphate anion. This brings about a compound that resists water, avoids easy evaporation, and resists a big range of temperatures. In the world of synthetic chemistry and chemical engineering, these liquids fill niches that older organic solvents no longer handle well. Pricing for [DMIM][PF6] remains higher than standard solvents because its production process demands careful handling and specific equipment for purity and yield, but the benefits often outweigh the costs in advanced applications.

Physical & Chemical Properties

This compound stands out because of its clear liquid form and faint odor. Boiling point doesn’t fit the classic sense, since the liquid breaks down before it boils. Melting points usually fall between 40 °C and 60 °C, depending on the degree of purity and moisture exposure. [DMIM][PF6] dissolves non-polar organics well but barely mixes with water, providing a sharp contrast to chloride-based ionic liquids. That water resistance turns out handy for electrochemical setups and extraction processes. Heat stability goes above 350 °C in inert conditions, but with air and moisture, breakdown happens sooner. Electrical conductivity remains modest—lower than shorter-chain analogs—because the decyl group slows down overall ion movement. Its hydrophobic profile makes separation from water straightforward, an advantage in cleaning and recycling steps.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Chemists doing laboratory work with [DMIM][PF6] monitor labels closely for purity, water content, and trace metal levels. Trusted suppliers define grades based on these features, with technical and research grades indicating whether certain contaminants might interfere with experimental goals. Clear labeling with full molecular formula, batch numbers, and CAS registry numbers helps avoid mix-ups and supports trust in the handling chain. Most containers include hazard pictograms warning against ingestion, inhalation and skin contact, with storage advice limiting exposure to light, humidity, and high temperatures. Batch-specific data sheets often include detailed NMR and IR spectra, supporting identity checks and cross-lab reproducibility.

Preparation Method

Production of [DMIM][PF6] depends on a two-step synthesis. It starts with an alkylation reaction, where 1-methylimidazole and 1-bromodecane combine to make 1-decyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide. Purifying this intermediate takes time and practice—residual water and unreacted reagents must be kept out. The next step uses metathesis: reacting the bromide salt with potassium hexafluorophosphate in an organic solvent, usually under nitrogen atmosphere. Stirring and slow dropwise addition let the hexafluorophosphate ion swap for the bromide, forming the desired ionic liquid and a precipitate of potassium bromide. This product gets extracted, washed, dried under vacuum, and sometimes filtered over activated alumina or charcoal to remove fine impurities. Each step matters, because any shortcut or oversight can clog up equipment or drag down product purity.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

On the bench, [DMIM][PF6] resists easy chemical attack from acids and bases at moderate concentrations, which stands in contrast to salts that carry more fragile anions. Under strong nucleophilic conditions, PF6- can sometimes hydrolyze, yielding hydrogen fluoride and other byproducts that complicate recovery. The imidazolium cation itself sometimes sees modification, with researchers swapping out the decyl group for other alkyl chains to produce families of related solvents. Beyond these, the ionic liquid can help catalyze reactions or serve as a recyclable reaction medium for Suzuki couplings, Diels-Alder reactions, and more. Its use as a supporting electrolyte in electrochemical research remains popular, and studies explore immobilizing functional groups onto the imidazolium ring for novel separation processes.

Synonyms & Product Names

In research catalogs, [DMIM][PF6] sometimes appears as 1-Decyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate, C10MIM PF6, or decylmethylimidazolium PF6. Some laboratories drop the “1-” prefix for brevity, and a few shorthand scripts use DMiM·PF6, which can confuse newer users. Recognizing synonyms helps avoid mishaps, especially during collaborative work or multi-country projects where translation and regional standards come into play.

Safety & Operational Standards

Safety protocols with [DMIM][PF6] mirror those for handling most ionic liquids: use gloves, goggles, and proper ventilation. Even though this compound doesn’t evaporate like old-school solvents, skin contact poses long-term health concerns. The PF6- anion can hydrolyze, releasing tiny amounts of hydrogen fluoride gas if water sneaks in. HF poses big risks, causing burns and complex reactions with calcium in the body. Full local exhaust and sealed storage help lower these risks. Disposal calls for cautious waste collection, with lab managers following hazardous waste codes specific to fluorinated materials. Handling guidance from the European REACH database and North American GHS recommendations underpins much of current best practice in lab and industrial environments.

Application Area

Researchers depend on [DMIM][PF6] for its balance between hydrophobicity and ionic strength. Separation science takes advantage of this for liquid-liquid extraction of heavy metals, organic toxins, and pharmaceuticals from water. Electrochemists rely on the compound as a medium for electrodeposition and as a component in ‘green’ batteries and capacitors, searching for alternatives to organic solvents that leak and degrade. Material scientists dissolve specialty polymers and nanoparticles in it, and environmental engineers prize it for its low vapor pressure. Extensive testing in chemical catalysis supports its use both as a solvent and, in some cases, as a reagent or co-catalyst, often with lower yields of hazardous byproducts than comparable systems.

Research & Development

Innovation around [DMIM][PF6] keeps moving forward in universities and corporate labs. Teams improve synthetic yield, recycle routes, and scale-up procedures, especially to reduce the cost of production and environmental impact. Investigators dig into the detailed surface chemistry when the liquid interacts with metals, glass, or organic films, hoping to create coatings, membranes, or porous supports that outperform older materials. On the green chemistry front, studies measure the impact of ionic liquid residues on water and air, since regulators and green certification bodies raise standards every few years. Machine learning gets applied to predict structure-property relationships between different ionic liquid variants. Academic grants keep funding work on designing more selective and less toxic derivatives, with the aim of creating safer alternatives for both industries and research users.

Toxicity Research

Toxicity questions surround every new solvent, and [DMIM][PF6] faces careful scrutiny. Tests in aquatic environments suggest moderate toxicity in freshwater invertebrates, with higher resistance seen in bacteria and algae. Researchers point out that the PF6- anion represents the greatest threat, because breakdown releases fluoride and other byproducts that persist in water and agitate biological systems. Chronic exposure in lab animals shows effects on liver enzymes and body weights, with dose and exposure length shaping outcomes. Wastewater treatment plants feel pressure to develop systems that trap or degrade ionic liquid runoff before it spreads in streams and rivers. Safety data sheets and government advisories tell chemists to minimize releases and always wash exposed surfaces, with extra checks for workers who handle these materials daily.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, [DMIM][PF6] stands on the cusp of broader adoption if cost, toxicity, and recyclability challenges get tackled. Startups chase technologies that reprocess spent liquids into fresh batches, slashing both waste and expense. Computational design promises next-generation ionic liquids with more predictable behavior and lower ecological impact. Renewable feedstocks for the imidazole ring and decyl group could cut the dependence on fossil sources. Governments and regulatory bodies keep raising the bar for solvent safety and disposal, which may reshuffle the ionic liquid landscape yet again. If new variants can sidestep persistent toxicity without losing performance, research and industrial use of [DMIM][PF6] and related compounds could unlock cleaner, safer chemical processes for years to come.

The Role of Unfamiliar Chemicals in Familiar Places

Nobody grows up thinking they’ll run across something with a name like 1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hexfluorophosphate. Yet this tongue-twister shows up in surprising spots. If you’ve watched the progress of green chemistry, you probably noticed ionic liquids get attention because they don’t evaporate like most solvents. As someone who has watched labs try to avoid classic toxic solvents, I’ve seen the frustration of streams of fumes, ruined samples, and complaints about headaches. This chemical, known in science circles as an ionic liquid, gives chemists a new tool that changes how reactions and clean-ups work.

Why Chemists Reach for This Compound

Picture a messy experiment: traditional solvents like acetone and toluene splash around, sending dangerous vapors into the air. 1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hexfluorophosphate doesn’t do that. It barely budges from the flask as a vapor. That matters for anyone tired of breathing strange fumes. Industrial chemists prize it for its stability, both at high heat and in water. Its strong “ionic” nature makes it a brave solvent for chemical reactions that can’t happen in regular liquids.

The main draw comes down to the push for sustainability and safety. Reactions that used to leave trails of waste now run in a safer, more controlled way. In electrochemistry, companies turn to this chemical for tasks like battery development or metal plating, where old solutions meant hazardous byproducts. Researchers who once wore double gloves just to pour solvents have switched to this ionic liquid and talk about lower risks.

What Science Says

Journals cite its ability to dissolve stubborn organic and inorganic compounds. Tech companies, hungry for greener electronics, experiment with it during the production of solar cells or specialty batteries. In my experience, every time one of these “designer solvents” enters the market, skepticism runs high. Some say, “If it’s that good, why isn’t everyone using it already?” The answer often comes down to cost, expertise, and the inertia of old habits.

The truth comes out in the numbers. Studies show certain ionic liquids cut down volatile organic compound emissions by over 80%. That lowers health risks for workers and researchers. It helps labs work toward regulations that limit atmospheric pollution. Environmental groups and regulatory agencies pay attention here, not out of hype but necessity. As the list of contaminated waterways and toxic spills grows, non-volatile options like this one stand out.

Questions and Troubles

No chemical solves every problem. Critics ask about breakdown products once the ionic liquid leaves the lab. Some reports mention that, given the wrong conditions, the fluorine in the molecule could form toxic byproducts. Evaluating its life-cycle becomes crucial. Green chemistry does not just swap out bad ingredients for untested ones; proper assessment makes the difference between improvement and regret.

What Could Help

The next step isn’t to replace all solvents overnight. Instead, education about proper handling and disposal puts power in the hands of scientists and industrial workers. Regulatory standards can keep surprises at bay. If a lab considers a switch, the process begins with understanding the chemical’s strengths and limits. That approach beats the cycles of chemical regret—when one quick fix just leads to another risk down the road.

Progress in chemistry rarely feels flashy. Step by step, new compounds like 1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hexfluorophosphate hand us safer choices. With vigilance and fact-based assessment, scientists can adopt new tools that improve both results and peace of mind.

Why Extra Care Matters

Anyone who has handled specialty chemicals knows they each carry their own risks. For a compound like 1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hexafluorophosphate, every step in the lab deserves both focus and respect. This isn’t kitchen science. A quick search through PubChem and OSHA guidance shows this ionic liquid can irritate skin and eyes, and it doesn’t react kindly to water or strong bases. That means every touchpoint from storage to spill cleanup holds weight.

Personal Protective Equipment You Actually Need

Splash goggles, not simple glasses, stand between you and some pretty unpleasant eye injuries. I once skipped the splash goggles with a less risky solvent and regretted it after a single splatter—lucked out with just redness, but never again. Face shields give another layer, especially if large volumes get involved.

Gloves make a huge difference, but not every glove stands up long-term. Nitrile gloves handle short exposures, but I’d opt for something thicker if I planned much handling. Laboratory coats or aprons — always lab-only, never out into general spaces — save both skin and clothes from contamination.

Handling and Storage Means Doing the Little Things Right

Store this compound in sealed containers, away from moisture and open flames. Humidity can lead to hydrolysis which may make the compound hazardous. Ventilated storage areas control exposure to fumes. In one lab, we had a small leak in a poorly ventilated cupboard. The lingering chemical smell stuck around for days, a reminder of how things can creep up if little details get overlooked.

Never eat, drink, or keep food nearby when working with it. Designate a workspace where only chemical handling happens, and make cleaning up spills part of the daily routine. Use spill kits made for ionic liquids, not just paper towels or sponges, since those don’t fully soak up or neutralize these compounds.

What to Do If Things Go Wrong

Anyone who’s spent time in laboratories knows accidents slip through even good habits sometimes. Eye washes and safety showers need to work, no exceptions. Make a habit of checking them weekly. If this liquid hits your skin, remove contaminated gear right away and wash with plenty of water. For eyes, flush them using an eyewash for at least 15 minutes.

Inhalation can irritate the lungs. Work inside a fume hood. If any signs like coughing or throat burning pop up, step away and get fresh air. The Material Safety Data Sheet offers guidance, but it’s better to have clean air from the start.

Building a Safety Mindset

Most accidents come down to routine breaches, not major mistakes. Take time to label everything clearly. Communicate with your coworkers — if you see a spill or a missing glove box, say something. Lab safety builds on small actions: checking PPE stash, updating labels on bottles, reviewing emergency plans, and double-checking procedures for disposal.

Waste disposal brings another challenge. Ionics like this don’t just rinse down the drain safely. Use sealed chemical waste containers, and hand them off to certified hazardous waste handlers. Keeping these chemicals off the streets and out of drains protects both people and the environment for the long run.

Bringing caution and common sense into every step helps keep labs safe and science moving forward.

What Scientists Say About Solubility

Anyone who spends time around chemical labs knows mixing stuff in water is often the first step in figuring out where things belong. 1-Decyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate, usually called [C10mim][PF6], lands in a group of chemicals called ionic liquids. Some ionic liquids blend right into water, others avoid it. This one, with its decyl chain hanging off an imidazolium ring, starts to tell a story just in that long hydrocarbon tail.

Straight Talk on Molecular Structure

Looking at its molecular structure, the long decyl (ten-carbon) chain makes the molecule act nonpolar in ways that show up in everyday life. Think of oil and water refusing to mix in your kitchen. The more nonpolar pieces stuck on, the less eager the molecule feels toward dissolving in water. Scientists call this "hydrophobicity," but really it’s all about which club these molecules want to join — water-lovers (hydrophilic) or water-avoiders (hydrophobic). The PF6 anion also resists water, so both sides steer clear of mixing well with H2O.

Research and Real-World Observations

Several years ago, chemists in academic groups put this ionic liquid to the test. They ran experiments, mixing [C10mim][PF6] into water at different temperatures and concentrations, and found it just doesn’t want to dissolve much. Instead, it forms two separate layers at room temperature. This has shown up in published research articles from groups in Europe and Asia, and results sound the same whether the journal is about green chemistry or physical chemistry. Bottom line: its solubility sits at less than a milligram per milliliter, sometimes down near parts per million.

Why Low Solubility Matters

The low solubility turns into both a feature and a limitation. For jobs where you don't want the solvent to disappear into water (such as extractions from aqueous mixtures, or separation processes), [C10mim][PF6] actually turns out handy. It stays as a separate layer, which helps with recycling or removing target compounds from water-based mixtures. In some cases, its stubbornness about mixing brings big advantages in cases where chemists can’t have ionic substances leaching into water supplies. This characteristic led to exploration in waste treatment and selective extraction.

Safety and Environmental Notes

It’s worth mentioning environmental impact. While ionic liquids sometimes get the “green” label, their water resistance raises questions about accumulation and breakdown in the wild. Hardly anything just disappears in a waste stream. Regulatory agencies point at concerns about stability, persistence, and potential toxicity. Peer-reviewed studies suggest some imidazolium-based ionic liquids can linger in soils and water, and breakdown can be slow. Therefore, careful waste handling matters, even if the stuff doesn’t actually end up in the water during normal use.

Where Does This Leave Us?

For those working with [C10mim][PF6], direct water dissolution seems out. To handle this practically, researchers use co-solvents or surfactants, or rely on the biphasic (two-layer) system. Sometimes scientists tailor the cation or anion side for better water solubility, switching chain lengths or subbing in other elements. Based on current facts and studies, this specific ionic liquid finds its sweet spot away from pure water, mostly in specialty extraction or chemical separation work.

Moving Forward

People should handle [C10mim][PF6] with knowledge and caution — good chemistry always comes down to understanding your tools. Effective training in chemical handling, proper lab waste protocols, and ongoing literature review help prevent unexpected headaches, for lab workers and for the environment. Pulling clear answers from chemistry books gives anyone working with these compounds a stronger foundation, and that kind of chemical literacy always pays off.

The Science at Eye Level: What Are We Looking At?

If you've spent any time in a chemistry lab lately, you probably noticed the growing popularity of ionic liquids. These substances often show up where researchers need stable solvents that stay liquid at room temperature. Among them, 1-Decyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate, or [C10mim][PF6], pops up in papers and patents. Its name can trip people up, so let’s break it down to see what makes this molecule tick.

Breaking Down the Name: Piece by Piece

Let’s start with the cation: 1-Decyl-3-methylimidazolium. You get a five-membered ring called imidazole. Attach a decyl group—a straight chain with ten carbon atoms—to the nitrogen atom at position 1. Add a methyl group (CH3) at position 3. Suddenly, you’ve got a bulky, oily ion that doesn’t like to stick with similar ions. This setup keeps the ionic liquid from crystallizing, so the substance remains liquid even at room temperature.

The anion, hexafluorophosphate (PF6−), brings six tightly packed fluorine atoms around a central phosphorus atom. This anion won’t react with many things and keeps the compound’s electrical charge stable. That stability is one reason people find this salt useful in demanding applications.

Why Lab Techs and Scientists Reach for It

I’ve seen researchers scramble for solvents that won’t evaporate, corrode metal, or flinch in the face of heat. Traditional solvents like acetone or toluene evaporate quickly and pollute the air. By contrast, 1-Decyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate holds steady, even when temperatures go up. The unique properties—low volatility, thermal stability, solvency—open doors for green chemistry, electrochemistry, and material science.

The Environmental Side of the Story

No compound comes without headaches. While ionic liquids can lower emissions and cut back on flammable solvents, the hexafluorophosphate anion raises red flags. PF6− can release toxic fluoride byproducts under the wrong conditions, especially at high temperatures or in water. This undercuts the “green” reputation sometimes given to ionic liquids. I’ve talked with colleagues who work on environmental impact, and they keep a close eye on these fluorinated ions. For real-world use, chemists need to weigh the stability of the compound against the risks linked to toxic breakdown products.

Where Does the Field Go from Here?

It makes sense to keep pushing for safer, friendlier substitutes that don’t carry the environmental baggage of PF6−. Some research teams experiment with anions like tetrafluoroborate or organic ions, hunting for sauces that blend function with safety. Regulations and careful chemical stewardship should take center stage. Lab protocols should target containment, recovery, and responsible disposal to sidestep contamination. Open data on long-term effects could steer everyone, from manufacturers to graduate students venturing into the field. In the bigger picture, clear-headed conversation and science-based choices keep chemistry growing without losing track of health or planet.

Looking at Structure, Thinking About Impact

1-Decyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate sits right at the crossroads of modern chemistry. The interplay between its molecular structure and practical concerns forces us all—chemists, environmentalists, industry leaders—to dig deeper. The real challenge isn’t just understanding these molecules but using them wisely, always watching for safer and smarter alternatives down the road.

Handling a Chemical Like This Calls for Rigor

Storing 1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hexfluorophosphate stands out as more than just another checkbox in the lab routine. This compound, widely used in electrochemistry and solvents research, brings some practical hazards along for the ride. Ignoring its safe storage doesn’t just risk equipment—it impacts people. Plenty of research labs and industrial settings have faced incidents by underestimating how even “safe” ionic liquids can behave under the wrong set of conditions.

Choose Containers That Don’t React

Using the wrong container leads to big problems for this substance. Glass often tops the list. Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) containers also perform well, especially in situations where people worry about leaching or reaction with the vessel. This chemical can react with water to release hydrofluoric acid, which proves both toxic and corrosive. A loose-fitting lid or a slight crack in a cap opens a door no one wants. Tight sealing must go beyond “good enough.”

I’ve seen colleagues meticulously label and double-bag bottles, building in a backup if the first layer fails. Clear labeling keeps other workers or students from making dangerous mistakes. Anyone who has worked with strong ionic liquids knows a simple plastic squeeze bottle from the grocery store won’t cut it.

Temperature Plays Into Chemical Stability

Temperature control rarely feels exciting—until a sample breaks down on a shelf or reacts with humidity in the air. Many labs set chemical storage between 2 and 8°C for ionic liquids like this one. Heat speeds up unwanted reactions, and even a day left near equipment exhaust fans heats things up fast. I learned early that thermally unstable samples quickly become the stars of spill reports. Strong temperature swings in storage closets can destroy an expensive supply of this chemical before it ever reaches an experiment.

Water and Moisture: Enemies to Watch Out For

Water poses a specific risk with 1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hexfluorophosphate. It does not take much humidity for this substance to start reacting, breaking down into toxic byproducts. Labs that keep it in a dry box or use desiccants protect their staff and materials. This is one of those places where a $10 jar of silica gel can save thousands—and big headaches. I once saw water-wicking packs line every shelf with ionic liquids just to push the odds in everyone’s favor.

Spill Kits and Emergency Gear—Always Close At Hand

No matter how careful storage protocols seem, spills or leaks happen. A good workplace keeps neutralizing agents, protective gloves, face shields, and ventilation ready to go. Getting into the mindset of assuming a spill will occur sets up better outcomes. Some researchers I’ve met keep their spill kits refreshed and labeled right by the cabinet, not locked away in a hallway. Quick response can mean the difference between a minor clean-up and a ruined workspace.

Education Fosters a Culture of Responsibility

No one benefits from a cavalier approach to chemical storage. Supervisors do best by drilling the specifics into new team members and providing reminders for experienced ones. Training that focuses on real cases like inhalation risks or accidental hydrofluoric acid formation sticks better than just reading guidelines off a poster.

Taking short-cuts on storage, even once, shuts the door on safety. Direct conversations and walk-throughs give everyone the chance to see what real care looks like. After all, responsible chemical storage is not only about following a checklist—it’s about protecting people who trust each other in the workspace.