1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate: A Deep-Dive Look

Historical Development

Chemists started exploring imidazolium-based ionic liquids in the late 1990s, looking for a replacement to volatile organic solvents. Eager to sidestep flammability, toxicity, and pollution, the search gained ground with the adoption of fluorinated anions, which brought thermal stability and chemical resistance into focus. 1-Decyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate landed attention as a variation that improved both solubility and process compatibility across several fields. This adaptation did not appear overnight. Years of iterative synthesis and property-tuning provided insights about long alkyl chains, hydrogen bonding, and ion transport. By the 2010s, research groups globally started publishing on ionic liquids like this for catalytic applications, extraction processes, and even medicinal use, highlighting both its promise and the need for caution.

Product Overview

1-Decyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate emerges as a room-temperature ionic liquid, comprised of a decyl-substituted imidazolium cation paired with a trifluoroacetate anion. Its behavior stands out in scenarios requiring negligible vapor pressure and non-flammability. Usually forming a clear to light yellow liquid, it handles moisture from air without breaking down. Chemically, broad chemical stability grows in value for tasks ranging from catalysis to electrolyte design. Many suppliers provide this compound at high purity grades, reflecting the growing need for reproducible research in laboratory and industrial settings.

Physical & Chemical Properties

This ionic liquid presents as a viscous fluid at room temperature with a density hovering around 1.1-1.2 g/cm³. Its melting point sits far below water’s—often well below room temperature—making it viable for liquid-phase processes at standard conditions. The trifluoroacetate anion helps boost both polarity and thermal resilience; decomposition temperatures exceed 250°C in most cases. Solubility profiles look wide: it mixes with polar and some nonpolar organic solvents, and absorbs moderate amounts of water without prompt loss of function. Viscosity increases with longer alkyl chains, which can make stirring—a real factor in process scale-up—a hassle at times. Still, the presence of both hydrophobic and hydrophilic groups proves useful in complex separation or extraction processes.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Manufacturers often ship 1-decyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate with labels marking purity (≥98% for most lab uses), moisture content, refractive index, and precise CAS registry number. Container materials resist corrosion and leaching, generally sticking to glass or PTFE-lined bottles. Mass spectrometry or NMR documentation sometimes gets included, particularly for researchers needing evidence of batch-to-batch consistency. Storage should avoid direct sunlight, strong oxidizers, and open flames. Transport guidelines track with regulations on Class 9 miscellaneous hazardous materials, a baseline for international handling.

Preparation Method

The typical synthesis takes a two-step approach. First, alkylation of 1-methylimidazole with 1-bromodecane generates 1-decyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide. The resulting intermediate, after purification, undergoes anion exchange with sodium trifluoroacetate or silver trifluoroacetate in aqueous solution. Following phase separation and repeated washing, the ionic liquid gets dried under vacuum to strip out water and extraneous ions. Lab chemists usually confirm purity using NMR and elemental analysis. Higher production volumes rely on batch or continuous reactors, automated washing, and rotary evaporation for solvent recovery.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Known for its near-inert chemical nature, 1-decyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate functions mainly as a medium rather than a participant. Yet, it does not completely escape side reactions—particularly at high temperatures or in the presence of strong nucleophiles. On occasion, the trifluoroacetate anion hydrolyzes or decomposes if exposed to strong acids. Chemists sometimes swap the anion for different functional groups, tuning the liquid’s polarity and hydrogen-bonding capacity. The alkyl chain length can get tailored through straightforward substitutions in the alkylation step, offering a way to match viscosity or solubility for specific applications.

Synonyms & Product Names

You find this compound marketed under several names: 1-decyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate, [C10mim][TFA], or decylmethylimidazolium trifluoroacetate. Commercial catalogs sometimes shorten to C10mimTFA or C10MIM-TFA. Differences in systematics or abbreviations come from supplier conventions or prevailing research terminology. It pays to double-check structural diagrams, especially since imidazolium ionic liquids have extensive naming overlap.

Safety & Operational Standards

Every laboratory and industrial process should treat 1-decyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate with respect. Direct skin or eye contact leads to irritation; prolonged exposure may trigger severe effects depending on individual sensitivity. Inhalation of vapors remains unlikely due to low volatility, but splashing or aerosol formation presents a risk during handling or cleaning. Safety data sheets urge gloves, eye protection, and, for larger volumes, fume hoods or splash shields. Environmental discharge rules treat this as a substance of concern—authorities in the EU and North America demand responsible disposal via incineration or certified chemical waste facilities. Safety protocols, such as secondary containment and routine ventilation, bring peace of mind in shared lab spaces.

Application Area

Demands for sustainable and high-performance solvents put this ionic liquid in the crosshairs of green chemistry. Processes such as biomass pretreatment, extraction of rare earth elements, and as electrolytes in electrochemical cells show clear benefits from lowering volatility and expanding solvent windows. Its interesting dual-phase solubility profile allows cleaner separations in organic synthesis. In catalysis, this medium allows certain metal catalysts to stay active longer or operate at lower temperatures, making reactions more energy-efficient. Pharmaceuticals and biomolecule extraction laboratories test this ionic liquid for its dissolving power without denaturing target molecules. The electronics industry, keen on better solvents for material processing, also shows growing interest.

Research & Development

University labs and industry R&D branches investigate both fundamental chemistry and engineering-scale use. Analytical chemists explore transport properties while synthetic teams tweak the core structure for better compatibility with new reaction types. Pooling data from spectroscopy, chromatography, and calorimetry speeds up discovery cycles. Collaborations with environmental scientists target methods for recovery and recycling, key to keeping production sustainable. Pilot plants in Asia and Europe gather performance metrics on continuous extraction or flow chemistry platforms. As soon as promising results appear, demand for sample volumes spikes, highlighting a feedback loop between bench and production.

Toxicity Research

Health and safety groups remain wary of ionic liquids, including 1-decyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate. Early evidence pointed out low acute toxicity compared to traditional solvents—fish, daphnia, and earthworms survived higher concentrations. Yet chronic exposure paints a murkier picture. Long-alkyl-chain imidazoliums bioaccumulate, and their breakdown in soil or water creates persistent compounds. Limited human studies underscore the need for proper ventilation, gloves, and spill control. Toxicologists experiment with in vitro models to gauge cytotoxicity, hoping to clarify pathways and reduce uncertainty over long-term effects. Authorities such as the European Chemicals Agency keep watch and update rules as new results land.

Future Prospects

If you care about scalable, safer, and more efficient chemical processes, 1-decyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate holds real promise. Ongoing work improves synthesis by using greener reagents and closed-loop recycling of byproducts. Digital tools accelerate property prediction, letting teams tune structure before any glassware comes out. Partnerships across academia, suppliers, and engineers focus on demonstration projects for waste minimization, improved storage stability, and easier recovery. If toxicity studies yield positive outcomes and disposal hurdles get addressed, this ionic liquid may shift from niche uses to a tool in everything from clean energy manufacturing to drug design. At its core, progress depends on robust safety data, real environmental risk analysis, and industry openness to new solutions.

The Real-Life Value of an Unusual Chemical

I remember first working with ionic liquids in a cramped university lab, hands stained with glass ink and a ventilation hood whirring. Back then, most of us saw these liquids as novelty materials, talked up at conferences but rarely put to work outside of basic research. Then, 1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate hit the scene. Here was a chemical that even skeptics paid attention to, and not just because the name is a mouthful.

Breaking Down Biomass: A Cleaner Story

One of the first times I saw this compound deliver results was in the breakdown of biomass. Wood chips, cornstalks—most people see waste, but anyone who cares about sustainable fuels knows the real problem is tearing apart cellulose and lignin without causing a mess. Scientists have shown that this ionic liquid can dissolve cellulose efficiently, skipping harsh acids or bases traditional industries rely on. With more countries pushing for cellulosic ethanol, this gives real hope for processes that don't pump streams of toxic byproducts into local waterways.

The science lines up: researchers from Oak Ridge National Laboratory published work showing that 1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate breaks down stubborn plant fibers faster and more completely than older solvents. I’ve watched this play out during small pilot trials, where handling became safer, and residual waste seemed easier to manage.

Greener Chemical Reactions: More Than a Buzzword

What caught my attention a few years later was its role in green synthesis. Some folks scoff at the idea of “green chemistry” as just feel-good marketing. In this case, results speak up. This ionic liquid doesn’t evaporate as quickly as organic solvents, so people running reactions in pharmaceutical labs or specialty chemical plants notice fewer emissions getting into the air. With exposure to toxic vapors a serious health risk—science backs this up with years of occupational disease data—the appeal grows fast.

One lab in Europe used the compound to boost yields in cross-coupling reactions, which matter for drug manufacture. Less waste and safer to handle—this is what keeps innovation real, not just stuck in PowerPoints.

Cleaning Up Metals and Recycling Electronics

Old circuit boards and used batteries pile up in storage yards in every country. Pulling precious metals out of that mix, especially gold, copper, and rare earth elements, usually means nasty acids and a lot of environmental headaches. In published studies, 1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate gave chemists an alternative: it can help dissolve target metals without the toxic fumes. It works at slightly lower temperatures, and it’s easier to recycle compared to traditional chemicals.

I’ve talked with waste managers who are willing to try new things—mostly because the old way is so expensive to clean up afterwards. There is still plenty of work to be done, especially around cost and the challenge of scaling up, but every little gain counts in keeping communities safer.

Promise and Practicality: The Road Ahead

Tracking the adoption of this chemical shows how research turns into action. At first, cost and availability slowed things down, but with better production and more companies jumping in, laboratories and industry started to take it seriously. The call now is for simple, tough tests in factories and labs to see where this material works best and what tweaks will make it better. People working in biofuels, pharma, and recycling have real motivation to cut pollution and keep workers safe. This ionic liquid gives them a shot at progress, not just promises.

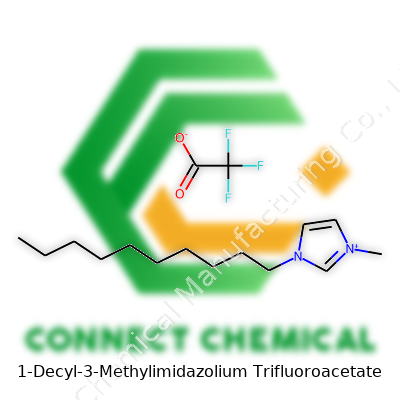

Getting Familiar With the Structure

Looking at 1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate, you see two distinct parts: the organic imidazolium cation and the trifluoroacetate anion. The imidazolium ring is pretty common in ionic liquids, and the name points out where all the groups land. A decyl group sticks to the first nitrogen, and a methyl group grabs a seat at the third carbon.

The cation ends up with the formula C14H29N2+. For the anion, trifluoroacetate gives us CF3COO-. Pair them together, and the full formula clocks in as C16H29F3N2O2.

Visualizing the Molecule

Picture the imidazolium ring at the center, with a long decyl chain stretching out. This extension shifts physical properties quite a bit. That flexible tail softens melting point and tweaks solubility. The trifluoroacetate group—recognizable by its trio of fluorine atoms—pulls in both polarity and a strong resistance to breaking down.

Chemists appreciate ionic liquids like this because they refuse to evaporate easily and often keep their cool even as temperatures climb. In my experience working with organic synthesis teams, people like these salts for their ability to act as “designer solvents.” You pick and match building blocks to fit a purpose. If the process wants less volatility and more ionic stability, this compound stands out.

Why the Structure Carries Practical Weight

It becomes obvious why industry leans on this salt. The long hydrocarbon chain offers compatibility with both organic and aqueous systems. In extractions, you don’t end up with phase separation headaches. The trifluoroacetate's strong electron-withdrawing group bolsters the molecule, making it less reactive. Trifluoroacetates often help protect compounds during delicate chemical steps, which I’ve seen firsthand while prepping air-sensitive catalysts.

Its structure also minimizes corrosion compared to older halide-based ionic liquids. That saves on equipment costs—a big deal for labs and processing plants. The molecule’s customizability goes beyond the decyl tail. Swap in a different alkyl group or tweak the acid anion, and you change its viscosity, solubility, or thermal profile. Colleagues in pharmaceuticals and materials science often take advantage of this, creating solvents for everything from drug synthesis to polymer casting.

Addressing the Challenges

Despite the perks, there’s a conversation about environmental persistence. Ionic liquids don’t always break down in nature. Research groups have started looking for ways to design more biodegradable versions. I sat in on a panel about finding green routes using bio-derived alkyl chains, hoping they’d strike a balance between function and environmental responsibility.

Toxicity remains a question mark too. While trifluoroacetate’s low reactivity usually means fewer side effects, fluorinated materials collect in water and soil. Labs and manufacturers keep an eye on waste protocols, using scrubbers and recovery systems so nothing slips into groundwater. Regulations keep evolving in this area and, from personal experience, projects that skip a thorough risk assessment slow down when compliance comes knocking.

Moving Forward with Science and Responsibility

As more sectors embrace specialty ionic liquids, the need for responsible design grows. Balancing performance with sustainability doesn’t always come easy. Strong collaboration between chemists, engineers, and environmental scientists builds better, safer molecules. That ensures breakthroughs stick around, both in the lab and in the world outside.

Why This Chemical Demands Attention

Working with chemicals like 1-decyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate takes more than just glancing at a safety label. Ionic liquids promise a gentler alternative compared to some more volatile organics, but their unique properties throw in a few extra wrinkles. I’ve seen researchers take shortcuts when dealing with similar compounds, and every time, hidden risks get a little closer to the surface. This trifluoroacetate salt carries a fluorous punch and the kind of long alkyl chain that makes spills stubborn and cleanups tricky. The comfort of low vapor pressure doesn’t excuse skipping basic safety. This is a chemical that sticks around—on skin, gloves, benchtops—so habits matter.

What Good Storage Looks Like

Good storage starts with dry, cool, and well-ventilated space. It clumps and becomes sticky in a humid corner, which means a tightly sealed bottle made from a material that resists corrosion—glass or compatible plastic, not any old polypropylene jar. Direct sunlight sometimes finds its way onto a crowded shelf, so moving this liquid into a darker cabinet reduces the chance of unwanted breakdown or “surprises” a year down the line. I once opened a bottle stored on a sunlit counter—the discoloration made it clear that wasn’t a great plan. Keep it away from acids, bases, and anything that likes to react; trifluoroacetate anion can play rough if it meets the wrong neighbor.

The Handling Routine That Works

No matter how eager someone is to dive into their synthesis, don’t skip gloves and splash goggles. Nitrile gloves hold up better to ionic liquids than latex, and any skin contact leaves a lingering trace that soap struggles to remove. Good air movement cuts down on any slow, unexpected release of fumes—even liquids like these can carry surprise odors or subtle hazards. Whenever transferring from one container to another, using a fume hood means that any tiny accident stays contained. My own spills with similar salts proved hard to wipe away cleanly, always leaving that trace residue that someone else finds days later.

Spill kits belong near the workspace. Dry absorbent pads meant for organic solvents work better than paper towels for picking up this oily mess. Mixing up a quick, careful response beats letting the liquid wander off the benchtop edge. For waste disposal, a separate, clearly labeled, and leak-proof waste jug avoids cross-contamination. Labmates make mistakes—clear labels and frequent reminders about dedicated waste go a long way. Sending this ionic liquid down the sink either clogs up pipes or enters waterways in forms that linger. The lab I worked in ran recurring “what not to pour down the drain” reminders, and that sort of repetition saved headaches more than once.

Supporting Everyone’s Safety

Basic training for new team members—walking through storage, transfers, glove donning, and clean-up—sets the tone for a responsible work culture. Each time I’ve mentored students, those first walkthroughs and rescue drills made them ask questions and call out broken habits later on. Review the safety data sheet, update it as new hazards become understood, and keep a digital and paper copy within reach. Amid the routine, don’t forget to connect real-world mistakes and practice to what the paperwork says. The best protection comes from habit, regular drills, and honest conversations that don’t brush aside “inconvenient” steps.

Taking Responsibility Beyond the Lab

As much as labs focus on internal safety, broader environmental responsibility matters too. Ionic liquids sometimes earn a “green” label, but long alkyl chains paired with fluorinated anions can resist breakdown in water and soil. I try to remind myself—and others—to track chemical inventory closely, avoid wasted purchases, and plan reactions efficiently. Never treat excess stock like it’s someone else’s problem. Good chemical management today keeps everyone safer tomorrow, from the benchtop to the waste stream.

Digging Into What Makes This Ionic Liquid Special

Not every chemical catches your attention the way 1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate does. Scientists working in green chemistry keep an eye on these compounds because ionic liquids bring real change to the lab bench. Their low volatility and surprising stability have already won them plenty of attention. Still, when it comes to practical work, people at the bench want to know: will it dissolve in water? Is it friendly with alcohols? Could it break down plastics, or stay stubbornly separate?

Following the Chain: Hydrophobic vs. Hydrophilic Choices

Anyone who has mixed oil and water knows chemistry likes to pick sides. Here, the long decyl chain attached to the imidazolium ring gives this ionic liquid some real attitude toward solvents. That chain repels water molecules, so you won’t see this salt acting like sugar in your morning coffee. Although the imidazolium core might be happy surrounded by water, the decyl tail nudges the balance away from easy aqueous dissolution.

If you look through published solubility data, the pattern holds. Solubility in water drops as the alkyl (carbon) chain grows longer. This compound, with its ten-carbon chain, stays mostly separate in water. Some sources estimate less than 1% solubility at room temperature, lower than similar salts with butyl or hexyl substituents. That’s useful if you want to separate organic from aqueous layers, but it means researchers have to pick solvents with a bit more punch.

Alcohols Offer a Middle Ground

Move over to methanol, ethanol, or propanol, and the story changes. Alcohols, blending polar and non-polar vibes, seem to put both sides of the molecule at ease. Chemists who use this salt for catalysis or separation get more workable mixtures, especially with ethanol. A 2020 study pointed out that the decyl-imidazolium family dissolves well in ethanol and methanol, so folks aiming for room-temperature reactions get reliable mixing. I’ve watched graduate students protesting the smell yet smiling at the clear layers in their tubes.

Stronger Stuff: DMSO and Acetonitrile

Those familiar with polar aprotic solvents already know DMSO and acetonitrile often save the day. They break apart solute-solvent barriers, especially for large organic ions. People find these solvents dissolve 1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate more thoroughly. Even with the stubborn decyl chain, DMSO’s reputation for “dissolving almost anything” holds up. But this comes with tradeoffs—cost, toxicity, and disposal are real-world limits. Labs interested in scale-up or greener processes keep reaching for ethanol for a reason.

Applications Driving Real Interest

It’s easy to see why researchers value this compound. Low water solubility means 1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate can act as a phase-transfer catalyst or help separate product layers. It shows up as a medium for enzyme reactions, pretreatment of biomass, and extraction of certain metals. In one startup project, we explored using it to extract rare earths from recycled electronics since its “double-sided” nature offered a clever way to pull out only what we wanted.

For practical work, figuring out the right solvent often defines a project’s success. Since ionic liquids like this one dodge evaporation and resist decomposition, their value in reaction engineering only grows. Industry and academia turn to them not just for efficiency but for greener options, replacing toxic or persistent solvents.

Knowing the Risks and Moving Forward

Because the decyl tail cuts water solubility, environmental persistence grows. Wastewater treatment and environmental impact studies need honest reporting. Researchers working under green chemistry banners have to support solvent choices with life-cycle analysis and safe handling routines. Alternative approaches—like combinations with biodegradable surfactants—are worth a closer look when scale ramps up.

For users in the field, understanding these solubility rules means less trial and error, safer experiments, and more reliable results. We’re not just picking molecular partners for fun—we’re building a safer and smarter chemical toolkit.

Understanding the Chemical

1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate has gained attention as an ionic liquid, promoted for its thermal stability and low volatility. Researchers and industry are eager to use it for dissolving cellulose, catalysis, and sometimes as a solvent that replaces strong acids or less stable organic liquids. These features all sound promising, but any chemical with this much versatility deserves a close look at its impact on people and planet.

Human Health Risks

Nobody wants to end up exposed to something that is advertised as “green” only to learn years later about hidden risks. The imidazolium family of ionic liquids generally gets flagged during toxicity screenings. Some types have shown mutagenic effects in cell cultures or can cause moderate skin and eye irritation. Data specifically for 1-Decyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate remains limited, but relying on the track record of its chemical cousins, caution makes sense.

Inhalation isn’t usually the problem since these compounds show low vapor pressure, but skin contact and accidental ingestion could pose risks. I can’t unsee lab safety sheets for similar imidazolium salts warning “avoid prolonged or repeated exposure.” More comprehensive, long-term toxicity data could settle nerves or expose surprise complications, but the science doesn’t look finished here yet.

Concerns for Water and Wildlife

Waste treatment centers are often not equipped to break down these new customized liquids. Ionic liquids resist breakdown by microbes in soil or treatment plants, so the release of this compound can lead to accumulation in water and potentially harm aquatic life. Studies have shown that imidazolium-based ionic liquids have toxic effects on fish and algae, disrupting reproduction and growth.

Trifluoroacetate, the anionic partner in this salt, also gets flagged. It’s a persistent organic pollutant, slow to degrade and known to move through groundwater. In the past, scientists have tracked trifluoroacetic acid all the way from manufacturing sites to remote lakes. Accumulation signals risk—it may not affect one fish quickly, but over time, whole populations could suffer.

Practical Solutions and Safer Alternatives

Putting new chemicals straight into the stream without much oversight leaves too much to chance. Better screening using bioassays that go beyond simple acute toxicity makes sense. Long-term studies in relevant species and in environmental samples could help reveal what standard studies miss.

Industry can act sooner by adopting closed-loop systems that trap ionic liquids and recycle them, so discharge drops closer to zero. Some teams are exploring greener alternatives based on simple, biodegradable ions rather than persistent fluorinated types. Academic labs can play a role as well—openly sharing both successful and unsuccessful results keeps hype in check and prevents the same mistakes from being repeated.

Researchers should publish rigorous, transparent studies on these chemicals, covering both occupational safety and environmental fate. Until studies deliver a solid safety profile with supporting facts, skepticism holds value in lab, industry, and community decisions alike.