1-Decyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide: In-Depth Commentary

Historical Development

Chemical innovation has often come from the desire to advance industry needs or answer tough research questions. In the late 20th century, scientists and engineers put their focus on ionic liquids, hunting for compounds that could shift the way synthesis, catalysis, and green technology work. Early examples struggled with volatility and toxicity, so the race centered on safer, more versatile salts. The introduction of imidazolium-based ionic liquids changed the game, bringing new physical stability and a broad spectrum of reactivity. By extending hydrocarbon chains and building in reactive vinyl groups, chemists tailored solutions with practical impact. Among these, 1-Decyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide appeared as a prime candidate for both industrial and academic exploration. Researchers saw how its design checked several boxes at once—thermal stability, solubility, and the potential for further functionalization. Its historical path reflects a hands-on, lab-driven approach aimed at creating something both useful in daily laboratory life and adaptable for new challenges as they arise.

Product Overview

1-Decyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide stands out as more than another fine chemical. It offers a flexible interface in the world of ionic liquids, combining the favorable properties of imidazolium rings with a vinyl moiety that invites targeted modifications. Chemists looking for a material that dissolves many types of polar and nonpolar substances find this compound opens doors to new experiments. It’s not just about mixing; this compound often acts as a facilitator. Realtors can tweak it for diverse uses—from electrical applications to polymer science—giving a sense of control over complex syntheses and separations which rarely comes easily from more traditional materials. For researchers who interact with ionic liquids in their daily work, 1-Decyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide often feels less like a product, more like a toolbox that shapes itself to experimental ambition.

Physical & Chemical Properties

This compound appears as a colorless or pale white solid at room temperature, but when exposed to gentle heating, it melts into a clear, viscous liquid. Unlike short-chain analogs, the decyl group confers low volatility and high hydrophobicity, which helps in reducing cross-contamination and limits environmental hazard during routine handling. The presence of the bromide anion grants good conductivity in solution and helps maintain charge balance in reactions gearing toward polyelectrolytes or as an antistatic agent. What grabs attention in the lab is its slight surfactant-like behavior, stemming from the long alkyl tail, so the molecule can bridge polar and nonpolar domains. It resists decomposition under moderate heating, which gives confidence when pushing strict thermal protocols during experimentation. Most imidazolium bromides leave a greasy residue, but with 1-Decyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide, that tendency appears somewhat lower, so cleaning up after syntheses takes a little less effort—a daily win.

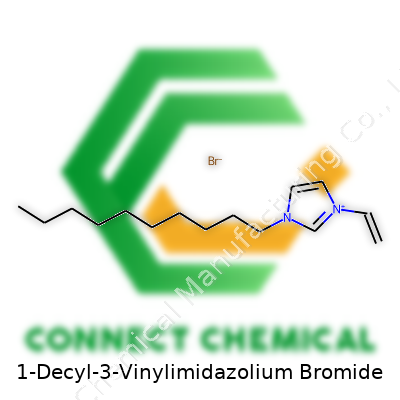

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Reliable supply channels publish detailed data sheets for this compound, and high-purity grades routinely hit 98% or higher. Labels report the chemical formula C15H27N2Br and a molecular mass near 331.3 g/mol. Moisture content stays under tight control—usually beneath 0.5%—since ionic liquids soak up water from the air, which can quietly change their behavior. Manufacturers print batch numbers, safety pictograms, and standards for trace impurities such as residual solvents and halide content. Storage instructions focus on keeping samples cool, in well-sealed containers away from direct sunlight, to prevent slow decomposition or polymerization at the vinyl functionality. From personal experience, labeling goes beyond regulatory compliance; it helps anyone in a shared workspace avoid costly errors. Shared containers without proper labels cause confusion, but this compound’s containers rarely lack the essentials thanks to tight regulations following international standards for chemical traceability.

Preparation Method

The route practitioners follow starts with commercially available 1-decylimidazole. Exposing this compound to vinyl-functionalized halides under carefully controlled temperature produces the targeted imidazolium backbone. Introducing bromide facilitates easy counterion exchange, keeping the system chloride-free when the experimental plan calls for it. Reaction mixture often goes through extraction and washing to remove unreacted starting materials. Reality in the preparative lab means purification steps matter; a single pass through a silica plug or careful crystallization can make the difference between a reproducible study and batch-to-batch headaches. Engineers investing in process scale-up design protocols to minimize waste streams and optimize yield, cutting costs where safety remains the top priority. This preparation process reflects a tried-and-true synthesis but still leaves room for tweaks when efficiency or purity push the boundaries of ordinary technique.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The halide counterion can often be swapped out for other anions in simple metathesis reactions, offering custom variants for electrochemistry, catalysis, or even pharmaceuticals research. Where the vinyl group shows up, it opens a gateway to polymerization reactions—stringing together many units to make ionic polymers with new sets of behaviors. Cross-linking trials in materials science use these groups to strengthen or functionalize surfaces, imparting antistatic properties, ionic conductivity, or controlled release. For those adjusting synthetic pathways to reduce process steps, this compound cuts down on the need for auxiliary reagents. Direct alkylations, quaternizations, or even “click” reactions deliver new derivatives for niche applications. The imidazolium ring structure remains – offering a reliably stable core through a range of functionalizations, from hydrophilic to more hydrophobic ends, depending on need. From hands-on lab work, success hinges on predicting how these modifications change both bulk and solution properties—surprises can set you back, but breakthroughs on a good day feel rewarding.

Synonyms & Product Names

Naming consistency matters so everyone in the lab pulls from the same chemical shelf. Common synonyms include 1-decyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide and decylvinylimidazolium bromide. Several chemical vendors track it by catalog numbers or with alternative naming notations adopted by industry consortia. In practice, such clarity streamlines purchases and eliminates confusion, especially where similar imidazolium liquids only differ by a methyl or ethyl group—one slip in ordering can derail a week’s planning. Digital inventory systems now flag common synonyms to prevent purchasing mishaps, but veteran technicians still check product codes by hand before signing off any major order.

Safety & Operational Standards

Safe working practice makes or breaks whether the benefits of a unique reagent outweigh the risks. Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) spell out hazards plainly—1-Decyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide produces eye and skin irritation on contact, and accidental inhalation of dust can complicate respiratory function. Workplaces handling it regularly use gloves, lab coats, and eye shields, while decent room ventilation cuts down on exposure. Spills need attention straightaway, mopped up with inert absorbent to avoid ingestion or environmental release. Since this compound displays good chemical stability but turns hazardous if heated to decomposition, carefully monitored hotplates and standard fume hoods guard against accidents. Disposal guidelines conform to halogenated waste protocols, keeping residues far from normal trash. Experienced lab staff reinforce proper handling with newcomers—peer-to-peer oversight builds safer habits than any posted guideline. Automation and closed-loop systems now help reduce direct interaction, lowering the odds of health incidents over time.

Application Area

Industry and academia both find this compound pulls weight far beyond rote experimentation. Polymer chemists covet the vinyl group for making ion-exchange membranes or new electrolytes for advanced batteries. Separations science takes advantage of ionic liquids like this one to extract rare earth metals, purify pharmaceuticals, or design solvent systems that cut down on flammable, hazardous organics. Researchers exploring green chemistry use it to minimize waste and bring down operational hazards linked to classic solvents and phase-transfer reagents. Even in electronics, this compound finds a place in antistatic materials or ionic conductors, especially where fine control over conductivity remains tough. Colleagues in biomaterials leverage it to build biocompatible coatings that resist fouling. From my own experience, sharing notes across departments triggers new ideas on how to stretch a product’s reach—from energy storage to environmental cleanup.

Research & Development

R&D thrives on versatility, and 1-Decyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide aligns with trends pushing sustainable chemistry agendas. Startups spring up targeting ionic liquids for low-carbon technology, and this compound often sits on screening panels for new industrial membranes or adaptable emulsifiers. Universities invest in projects testing its performance in catalysis, where it acts both as solvent and participant, unique among traditional salts. Development teams focus on improving recyclability, finding ways to harness the compound repeatedly with little property loss. In-situ studies use spectroscopy and specialized microscopes to peer inside reactions, revealing real-world behavior, not just textbook results. Current collaborations between industry and government labs push discovery farther, focusing resources on breaking technical barriers—energy storage, water purification, drug delivery—where small advances change markets.

Toxicity Research

Toxicity remains a pressing concern, since early ionic liquids earned reputations as both environmental heroes and potential health risks. Investigators now follow stricter protocols, running cell studies, aquatic toxicity tests, and breakdown analyses for every promising compound. 1-Decyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide usually passes acute toxicity hurdles at the low concentrations used for most lab work, but safety experts still flag its persistence in water and soil. Chronic exposure effects require more long-term data, so prudent labs invest in waste treatment and environmental monitoring. Real learning comes from tracking a chemical’s life cycle—from raw materials to end-of-life disposal. As users, we push for open data sharing, knowing that decades of experience and cross-disciplinary cooperation sharpen how risk is judged and managed for ionic liquids. Regulatory bodies respond to solid toxicity data, balancing innovation with environmental management.

Future Prospects

Anyone watching the technology pipeline sees a bright, expanding horizon for customizable ionic liquids. Efforts grow around using 1-Decyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide in composite materials for renewables, from solar cell encapsulants to supercapacitor electrolytes. Polymer researchers seek ways to lock it into renewable plastics for tailored ion flow and selective barrier properties. Environmental scientists test its behavior in pollutant extraction, searching for cleaner, more reusable alternatives. Venture capital leans into startups building proprietary technology on the back of ionic liquid know-how. I notice the academic side pushing for broad data sets, publishing methods for safer synthesis and charting long-term impacts from bench to environment. Demand pushes suppliers to scale up ethically, tracking every batch and updating protocols with each new hazard flagged. Progress, measured in small improvements, bends toward a safer and more versatile chemical future revolving around compounds just like this.

Where Science Meets Practical Need

1-Decyl-3-Vinylimidazolium bromide might sound like a chemical from a high school textbook, but it’s got boots on the ground in a bunch of fields. I learned about this ionic liquid from a friend who works in materials science. He told me that chemicals like this one don’t just get stuck on lab shelves; they make things happen in the real world. Not everything flashy in research ends up leaving the lab, but this one’s quietly found some purpose where it matters—especially where performance and safety are important.

Changing the Game in Polymer Science

Many folks don’t realize just how often new chemicals end up inside plastics and coatings. 1-Decyl-3-Vinylimidazolium bromide shows up here as a functional monomer. Scientists use it to tweak the properties of polymers. Its ionic nature brings electrical conductivity to the table, which regular old plastics never had a shot at. Think flexible displays, antistatic coatings, and high-end packaging that keeps your electronics safer. Polymeric coatings made with this chemical stick together better and handle more stress, which ends up meaning longer product life and less waste.

Taking On Environmental Clean-Up

Before my neighbor’s business tried filtering heavy metals from industrial waste, they relied on classic materials. Time and again, these didn’t trap enough metal or lasted only a few cycles. A research group ran a test using polymers built from 1-Decyl-3-Vinylimidazolium bromide. The chemical structure grabs on to metal ions and doesn’t let go easily. This helped the filtration process lock up more mercury and copper, cutting pollution at the source. The approach showed enough promise that several large wastewater plants now run trials, hoping to cut their compliance costs and protect local rivers.

Improving Batteries and Energy Storage

Anyone who’s sick of watching their phone battery drop to zero by late afternoon knows just how important battery research is. Engineers working with lithium-ion and other next-gen batteries keep running into problems with stability and safety. Ionic liquids like this bromide step in as solid electrolytes or as pieces of hybrid gels. Because the molecules won’t evaporate or ignite like classic solvents, batteries work longer and safer. Reports from university labs suggest replacing older electrolytes with ionic liquids improves performance, even during heatwaves and deep freezes.

Opening Doors to Greener Chemistry

Switching away from old-school solvents means less danger and cleaner air. I got this point while talking to a chemist at a start-up trying to make pharmaceuticals with fewer steps and less pollution. They replaced toxic liquids with 1-Decyl-3-Vinylimidazolium bromide in the reaction mix. Suddenly, parts of their synthesis used less energy and generated less hazardous waste. Chemical manufacturing is a huge source of environmental damage, so every improvement ripples outward. This approach still costs more than familiar ingredients, but prices may drop as demand grows.

What Can Make the Impact Bigger?

One stumbling point remains: scale. Most companies hesitate to commit until supply chains and pricing settle down. Government grants and partnerships could help here, as could industry-wide agreements focused on lowering waste and improving worker safety. As more sectors experiment with the chemical, new applications will come up. Personally, I think greater transparency about test results—from industry and academia—would motivate other engineers and chemists to give this compound a try.

People don’t always see the science behind cleaner water, safer electronics, and greener chemistry, but it’s there, quietly pushing us in the right direction.Understanding the Chemical

Holding a bottle of 1-Decyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide makes it clear this isn’t a chemical you want drifting around just anywhere. This ionic liquid, often used for organic synthesis or as a component in material science labs, reacts in some unpleasant ways if ignored. The chemical formula promises interesting reactions, but even the most promising tools lose value if they break down before use.

Real-World Storage Experience

Spending years around research labs teaches a few key lessons about chemical storage. It only takes one sweaty summer day without air conditioning to watch perfectly good reagents turn useless or dangerous. Sensitive compounds, especially salts like this one, demand dry air and a cool touch. Leaving the jar open or setting it near a window speeds up clumping, discoloration, or unexpected odor. Once moisture gets in, you can forget about reproducible experiments or reliable data.

Fact Check: Manufacturer Guidelines

Lab manuals and supplier recommendations both point to similar rules for this sort of ionic liquid:

- Avoid direct sunlight. UV rays start chemical reactions that even the best chemist can’t always reverse.

- Keep away from heat sources or fluctuating room temperatures. Temperature swings break apart stable molecules and shorten shelf life.

- Seal tightly after every use. Leaving the cap loose could mean more humidity and airborne particles creeping in. Moisture can cause hydrolysis, spoiling the compound’s properties.

- Store in a dry, dedicated chemical cabinet. Piling chemicals next to the sink adds risk. Even a quick rinse or splash can damage containers and contaminate chemicals.

Nothing beats reading the original Safety Data Sheet. It usually spells out required temperature ranges. Most call for a standard cool-room setup—15°C to 25°C is the typical safe range—though some labs lean toward refrigerated units for long-term storage. Refrigeration has its downsides, though, since moving between cold and warm spaces can cause condensation.

Safety Risks and Solutions

Mishandling storage isn’t a minor headache. A contaminated or degraded sample can mean failed syntheses, unpredictable reaction products, or even hazardous emergencies. I’ve seen more than one team lose precious time because solvents soaked up humidity and changed their expected behavior.Keeping chemicals in labeled, amber glass bottles with desiccant packs stands out as a simple solution. Silica gel packs work wonders for warding off those stray water molecules.

Regular checks also pay off. Take a minute each week to inspect bottles for signs of caking, cloudiness, or discoloration. Spotting trouble early saves you from costly cleanup or dangerous mishaps.

Moving Toward Responsible Storage

Labs build trust by demonstrating they know what they’re doing with every compound. Audit trails, electronic inventory, and well-trained staff give confidence that storage isn’t left to chance. Careless mistakes ripple through research and production—protecting your chemicals protects your results, your team, and the wider community.

Getting the basics right with 1-Decyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide means creating a routine that treats storage as a top priority. The discipline pays off with fewer wasted resources, more reliable experiments, and the peace of mind that comes from working safely.

Understanding What We’re Working With

1-Decyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide doesn’t come up in daily conversation, but it appears more often in research labs, especially in the world of ionic liquids and advanced chemical synthesis. The structure, built around the imidazolium core with a vinyl twist, helps it perform where many solvents hit a wall. Anytime chemists talk ionic liquids, they lay out benefits: lower volatility, customizable properties, and better potential for green chemistry. All that sounds good until it lands on the bench—then the big question hits: is it hazardous, and should we change our handling wheels?

Looking Hazard Straight in the Eye

Chemicals like this one aren’t household names for a reason. Standard safety data points out routes of harm that include skin, eyes, and lungs. Despite the reputation for “greener” chemistry, most imidazolium salts sit in a gray area. Acute toxicity numbers may not broadcast alarm bells, but that doesn’t let anyone shrug off gloves or goggles. In my own experience with similar compounds, the moment a drop touched skin, irritation flared up. More concerning—long-term risks often stay hidden, tucked in research papers and not always on the label. These compounds might disrupt cell membranes or pose environmental risks, especially if cracked down the drain.

No Shortcuts in the Lab

Safe handling isn’t about paranoia; it’s about learned caution. Daily lab routines often dull the sense of risk, especially when a chemical seems “safe enough” on paper. Labels may say “low volatility” but miss the bigger story: fine dust kicks up during weighing, or a tiny spill evaporates over the benchtop. Once, I watched a careless benchmate end up with a rash because they skipped the lab coat to “just measure a little.” Splash risk, dust inhalation, and skin contact: these hazards turn real if habits slip.

Regulations and Recommendations

1-Decyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide doesn’t land on most international lists of restricted compounds. This absence leads some to treat it with less respect than it deserves. But not showing up on government registries doesn’t mean the hazard vanishes. OSHA, NIOSH, and EU workplace guidelines all agree: if skin or respiratory risk exists, gloves and ventilation belong in the workflow. Chemical-resistant gloves, eye protection, and working within a fume hood set a clear standard. Waste disposal matters, too—organic salts like this can stick around in water, harming aquatic life.

Improving Culture, Not Just Compliance

I’ve learned there’s rarely a shortcut when it comes to chemical safety—especially with newer, less studied compounds like this. Information gets shared too lightly across labs. Mandatory safety sheets help but don’t replace real discussion or hands-on training. Scientific responsibility runs deeper than ticking boxes. Lab managers setting a strong example, inviting open talk about “near-misses,” and giving access to research on emerging hazards make a real difference.

Working Toward Safer Workplaces

As chemistry keeps evolving, so does the list of what we work with. Every new compound needs fresh eyes. For anyone planning on using 1-decyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide, it’s not about guessing hazard—it’s about acting with the confidence that protection stands between your work and potential harm. Gloves, goggles, and respect for the unknown have no substitute. Sticking to that mindset—no matter how routine the day—keeps labs productive and everyone going home unharmed.

Real-world Purity Standards

Folks in the lab know there’s always pressure to use chemicals that meet strict standards. Purity matters, not just for successful experiments, but also for peace of mind that results mean something. For 1-Decyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide, getting the right quality involves watching for purity percentages that usually land between 95% and 99%. Sellers tend to pitch their “high-purity” or “analytical grade” products at about 97% or 98%. These numbers aren’t just for show. Contaminants in ionic liquids have a habit of interfering with outcomes, especially where catalysis, electrochemistry, or advanced material science come into play.

Why Purity Isn’t Just a Number

Having spent my fair share of hours tracking down why a reaction won’t proceed as expected, I can say low-level impurities throw a wrench in the works faster than most students realize. Bromide-based ionic liquids in the imidazolium family, including this one, carry subtle but influential risks from impurities—leftover solvents, trace metals, water, or unreacted starting materials. These culprits play havoc with conductivity, stability, and catalytic performance.

Several suppliers provide very clear data sheets outlining purity by HPLC, NMR, or elemental analysis. Academic work often cites using compounds “as received” at 97% or higher purity since additional purification eats up time and money. Go much below 95%, and you step into muddy waters: filtration struggles, color changes appear, reproducibility tanks.

Trust but Verify: Documentation Matters

Don’t just scan for a high number on the label. Dig into how suppliers arrive at those percentages. Quality companies document their testing process, including chromatograms or NMR spectrums, not just blanket claims. Certification by ISO standards or consistent batch testing adds real trust—in the lab and in academic journals. Publications often call out “used without further purification” only after seeing those specification sheets. Sourcing from fly-by-night chemical vendors risks invisible but significant variations that aren’t worth gambling a grant-funded project over.

Possible Solutions for Buyers

Researchers wanting less hassle with inconsistent stock can lean on two habits: ask for a full Certificate of Analysis for each lot, and run spot-checks using NMR or simple IR if equipment is handy. Crowdsourcing recent experiences within the scientific community also helps. With the increased volume of open access publishing, many research groups now publish which supplier and catalog number delivered the best batch for their setup.

Price, Quantity, and Practicality

In the world outside of unlimited budgets, price comes into play. A jump from 95% to 98% can mean a noticeable bump in cost, but sacrificing purity to save pennies ends up costing more in reruns and troubleshooting. Before placing an order, weigh if the target experiment is high-stakes or preliminary. For exploratory synthesis, some might tolerate 95%. For anything sensitive, or for scaling protocols, aim for the best grade possible.

While the phrase “Purity above 97%” pops up frequently, those numbers only tell part of the story. The real win comes by coupling documented quality with practical checks. That way, whether you're working with 1-Decyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide for deep science or fresh application, the chemistry works with you and not against you.

Chemistry at the Intersection of Function and Flexibility

I remember walking into the polymer lab for the first time, the faint tang of solvents hanging in the air, and the well-worn benches cluttered with odd-shaped bottles. Chemists around the world find themselves seeking materials that bring new flexibility to polymer systems and push the boundaries of ionic liquid science. One compound that sparks curiosity these days is 1-decyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide. The structure, with its vinyl group hanging off the imidazolium ring, suggests real potential for creative polymer chemistry.

What Makes 1-Decyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide a Standout?

This molecule combines a long alkyl chain with the reactivity of a vinyl group. That vinyl group calls out to radical initiators, eager to join a new polymer chain. The imidazolium core, familiar to those working in ionic liquid labs, offers ionic conductivity and thermal stability, qualities that matter in energy storage, green chemistry, and advanced coatings.

In real world trials, researchers have shown that 1-decyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide can act as a monomer. Drop it into a flask with an initiator like AIBN, and the double bond cracks open, linking monomers into a polymer. This path brings a long hydrophobic tail alongside the positively charged ring, creating a backbone for specialty polymers that tackle tough separation challenges or deliver improved anti-static properties.

Shaping Ionic Liquids: Beyond Just a Solvent

People often talk about ionic liquids as solvents, but chemists see a toolkit for building new materials. The structure of 1-decyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide lets it serve as a building block for polymeric ionic liquids (PILs). Researchers from Asia and Europe have synthesized polyelectrolytes using vinylimidazolium compounds, finding that the resulting polymers maintain the desirable low-volatility and high-thermal-stability of classic ionic liquids, but add mechanical toughness.

These polymeric ionic liquids don’t just hold their own in the lab. They get tested in batteries, solid-state devices, and fuel cells. By tuning the alkyl chain length and the counterion, folks have found pathways to new electrolytes, membranes, and smart coatings. One drawback stands out—the bromide anion can sometimes limit ion transport compared to other options like bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide, so swapping anions with metathesis reactions becomes a practical move in advanced designs.

Tackling Challenges in Polymer Synthesis

Every synthesis brings questions about purity, yield, and performance. Using 1-decyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide in polymerization means careful control of temperature, initiator choice, and purification. Impurities can sabotage electrochemical performance or cloud up films. In my work, careful distillation and repeated washing have proven essential for building reliable polymeric materials from these ionic monomers.

Cost sits on every chemist’s shoulder. Custom ionic liquids can boost a project’s price tag fast. Scaling up requires collaboration between chemists and engineers, tapping both synthetic know-how and practical insight into purification and waste handling.

Looking to the Future

1-Decyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide earns respect for enabling creative routes to new functional polymers and advanced ionic liquids. With a combination of bench-top persistence and thoughtful teamwork, this molecule opens doors to real progress in sustainable materials and next-generation devices.