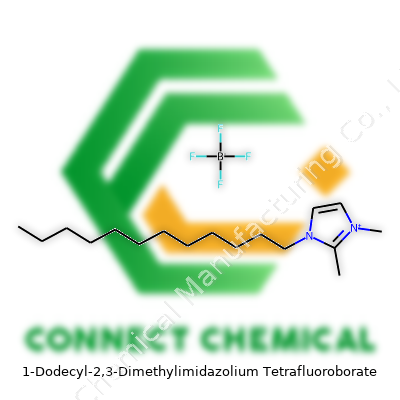

An Article on 1-Dodecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate

Historical Development

Anyone who follows advances in green chemistry will spot the shift that started to pick up in the late 20th century. Ionic liquids, like 1-Dodecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate, emerged from a frustration: Organic solvents often bring hazards, volatility, and environmental costs. Chemists focused on non-volatile, tailored liquids—seeing a chance to solve old problems in synthesis and catalysis. The imidazolium backbone, already recognized for thermal stability, set the stage. With new alkylation strategies developed in labs across Europe and Asia, a variety of imidazolium derivatives reached the benches of researchers aiming for less toxic, more durable alternatives. From 2000 onward, long-chained imidazolium salts like this one turned up in papers on catalysis, extraction, and advanced materials.

Product Overview

1-Dodecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate shows up as a pale, waxy solid or a viscous liquid, depending on its exact hydration and purity. Anyone working in a lab will notice the distinctive faint odor, an echo of its imidazolium roots. Chemists value this ionic liquid for its versatility: It dissolves in polar and moderately non-polar solvents. Unlike short-chain analogues, its dodecyl group brings low volatility and increased hydrophobicity. This product fits wherever non-traditional solvents and stable ionic media can improve a process.

Physical & Chemical Properties

With a molecular formula of C17H33BF4N2, this compound balances a bulky hydrophobic tail and a charged center. The dodecyl side chain, longer than in basic imidazolium salts, drops its melting point well below many other ionic compounds, making it liquid at moderate lab temperatures. Its density lands near 1.0-1.2 g/cm³, higher than most organic liquids but typical for ionic liquids. The tetrafluoroborate anion brings high hydrolytic resistance and helps keep the salt stable in water and common organic solvents.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

High-end suppliers always specify minimum purity, often 98% or higher, as water and halide impurities affect performance in catalysis and separation. Labels reflect key safety information—GHS codes signal irritant properties, and containers carry batch numbers for traceability. The CAS number pins this chemical firmly for regulatory compliance and inventory management. Anyone storing ionic liquids knows they need airtight bottles and cool, dry shelves, as humidity and dust can ruin purity.

Preparation Method

The most widespread route for making this salt starts with 1-dodecylimidazole. Reacting it with methyl sources like methyl iodide or methyl sulfate turns the 2,3-positions into methyl groups. Quaternization proceeds in solvents such as acetonitrile or toluene under nitrogen. Filtration and washing remove unreacted reagents. Anion exchange—using sodium tetrafluoroborate in water—swaps unwanted counterions for BF4-, yielding the desired product. Careful drying under vacuum ensures a low-water, high-purity result, key for reproducible results in applications.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The imidazolium ring opens doors for nucleophilic substitution on the dodecyl chain or N-alkylation at other positions, if needed. Researchers can bring in functional handles for further transformations—such as azide-alkyne cycloadditions or cross-coupling. The tetrafluoroborate part stands firm against alkali, acid, and mild oxidizing conditions, which means it survives reactions where traditional salts would fail. This structural flexibility means labs can design custom ionic liquids to target specific solubility or coordination needs.

Synonyms & Product Names

Literature may describe this compound as DDMIm BF4, 1-Dodecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, or as part of a broader family of alkylimidazolium tetrafluoroborates. Trade catalogs sometimes shorten the names to fit reference tables, but the imidazolium base always signals the ionic liquid class. Synonyms must be checked carefully—mislabeling often causes confusion when scaling between suppliers.

Safety & Operational Standards

Lab users rely on GHS and local legislation to guide handling. Direct skin or eye contact triggers irritation, and strict protocols require gloves, goggles, and lab coats. Good ventilation prevents inhaling faint fumes that some ionic liquids release on heating, especially near decomposition temperatures above 200°C. Most waste streams containing this salt require special containment, not just sink disposal, to prevent environmental contamination. Risk assessments and MSDS sheets confirm these procedures, securing lab safety and supporting green chemistry commitments.

Application Area

Chemists working on catalysis find this ionic liquid excels as a reaction medium for palladium-catalyzed couplings or alkylations. Its low volatility supports extractions of hydrophobic organics from water, with high selectivity for long-chained molecules. In electrochemistry, the compound’s wide electrochemical window fosters electrode stability, useful in energy storage materials and lithium battery research. Surface modification teams seek it for controlled dispersions of nanoparticles, beating out traditional surfactants in some scenarios. Environmental engineers look to these compounds for greener alternatives in extractions, where many organic solvents fall short in selectivity or safety.

Research & Development

Academic groups push for greener, more efficient methods of synthesis, often publishing data on recyclable catalysts that function in this liquid. Investigators have tracked how the structure affects microphase separation, aiming to tune properties for membrane or sensor technology. Industrial researchers seek scale-up routes to drop production costs, as clean preparation aligns with ISO and REACH guidelines worldwide. Journals overflow with new reaction types run “in ionic liquids,” boosting yields and simplifying product recovery.

Toxicity Research

Early excitement about ionic liquids cooled as toxicity profiles became clearer. Transparent reporting matters here. 1-Dodecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium salts show moderate toxicity in aquatic assays, mainly because long alkyl chains breach cell membranes. Ecotoxicological studies advise strict waste controls and recycling methods, especially for anything entering water systems. Labs monitor chronic and acute exposures, since some derivatives bioaccumulate over repeated contact. Researchers in this space push for structure-toxicity models to guide safer choice and next-generation design.

Future Prospects

Future work aims to balance performance with environmental and health priorities. Research already explores structure modifications to boost biodegradability and drop toxicity, without losing the unique benefits in catalysis or separation. Circular chemistry programs, powered by European and Asian government funding, invest in recycling strategies for used ionic liquids. Scientists focus on integrating bio-based raw materials to build the next generation of imidazolium salts. These changes hold the potential for sustainable scaling, with the hope that industry and academia will keep up the pace to match safety with progress.

Looking Under the Hood of a Modern Chemical

Every now and then, a long-winded chemical name pops up and raises a few brows. 1-Dodecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate might sound intimidating, but for researchers chasing clean chemistry, this mouthful often shows up in the lab. This compound belongs to the ionic liquids gang, which means it doesn’t behave like regular table salt or tap water. Instead, it acts like a liquid salt at room temperature, and that’s a big deal for science.

Promise in Green Chemistry

Many folks working on sustainable tech want alternatives to hazardous solvents. The beauty of many ionic liquids, including this one, comes from their low volatility. No choking fumes; spills stick around until cleaned up. Scientists jump on this trait, especially in organic synthesis, because it helps cut down air pollution in the lab. And let’s face it—no one enjoys working with a chemical that stinks up the place and risks health.

In my experience trailing the buzz at academic conferences, chemists keep circling back to ionic liquids for their customizable properties. Maybe you need something to dissolve stubborn polymers or separate tricky layers in a reaction. Tweak the side chains, swap out the counterion, and you get a liquid that fits the job. With dodecyl on its side, this imidazolium salt offers strong dissolving power for tough organics, making it valuable for folks building new materials or playing with nanotech.

Water Treatment and Extraction Workhorse

Some researchers use this salt to scoop up heavy metals or organic pollution from water. Traditional cleanup involves lots of energy or harsh chemicals. Drop an ionic liquid like 1-dodecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate into the system and, thanks to its affinity for dirt and oil, it pulls out contaminants fast. This “liquid extraction” happens without loading the air with toxins, and you can often recover and reuse the liquid afterwards.

Scientists who handle water treatment and mining waste know these intricate molecules don’t solve everything. The chemicals can get pricey, and separating them from treated water can turn into a puzzle. Tackling that, some labs have moved toward recycling protocols and cleaner synthesis methods that limit environmental leftovers.

Boosting Electrochemical Devices

Energy storage is hungry for new materials. Researchers rely on ionic liquids with big, chunky molecules like this one to fine-tune batteries and supercapacitors. These liquids hold onto their shape at high voltages and crazy temperatures where old-school solvents break down or catch fire. That’s why electric vehicle developers pay close attention to test results—no one wants a battery that fizzles in hot weather.

I’ve heard from engineers that materials like this often turn up in flexible electronics and solar research. Their chemical stability keeps circuits running longer, and the low flammability draws smiles from safety officers. Still, making these salts on a large scale pushes up the price tag, so the industry skates a balance between lab promise and market reality.

Getting Ahead of Challenges

No industry wants to swap out one risk for another. As the use of ionic liquids grows, researchers keep tabs on the environmental and health effects. Building simple, scalable recycling systems for spent ionic liquids will matter a lot, especially if the goal spins around real-world impact and not just academic headlines.

If chemical innovation teaches anything, it’s that new tools bring both new hopes and new headaches. By taking what works—safe handling, recovery, careful use—and being upfront about limitations, breakthroughs like 1-dodecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate have a good shot at helping both labs and industries move forward without leaving a mess behind.

Respecting What’s on the Label

The full name is a mouthful for most folks working in chemistry, but 1-Dodecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate shows up more often than you’d guess in lab research. A lot of chemists know this as an ionic liquid. It stands out because of its low flammability and high chemical stability. People might think it’s easy to handle, but the truth is safety isn’t automatic. Failing to handle it right creates headaches nobody wants, like contaminated samples or damaged containers. Years spent tracking down the source of a failed reaction or mystery leak shows how important it is to respect these chemicals, no matter how harmless they seem.

Moisture: The Sneaky Enemy

Plenty of good reagents get ruined by simple moisture exposure. The moment 1-Dodecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate meets water vapor in the air, it starts to pick it up. This isn’t just a little inconvenience—moisture can throw off experiments, create new impurities, and waste both money and time. I learned this the hard way as a student: a bottle left unsealed on the bench for an afternoon didn’t look any different, but its quality dropped. Not much is worse than repeating a long preparation just because a step got skipped during cleanup.

Temperature and Light: Treat It Like It’s Milk

Placing a bottle of this ionic liquid next to a sunny window or next to the lab radiator cuts down the shelf life. It’s not just a fussy warning; fluctuating temperatures can break down the bonds, which leads to loss of purity. The fluorescent lights in the lab might not seem strong, but over weeks or months, even that can promote mild decomposition. The difference between storing it in a cool, dry, dark cupboard and leaving it on the lab shelf becomes clear in chemical performance over time.

Choose the Right Containers

Chemists know that the wrong cap can make or break sample integrity. My team learned quickly during a hot, humid summer—using a plastic lid let in just enough moisture for the contents to clump up. Using strong glass with a tight seal fixes most of these headaches. Even if the container seems overkill at first, opening up a fresh sample for real research shows the payoff. Good containers also keep fumes contained, stopping contamination across samples, especially for those who use shared storage.

Label Truthfully and Date Everything

No one forgets the lesson of finding half a dozen mystery bottles in the back fridge, labels peeling, and writing smeared away. Proper chemical storage always includes labels with both name and date. Quick digital logs or even a sharpie save a lot of time and confusion later. If the container doesn’t get a fresh label, sooner or later someone risks grabbing an old, useless batch by accident.

Training Isn’t Just for Newcomers

It’s easy to forget the best habits once the lab routine kicks in. Refresher training on how to handle chemicals like 1-Dodecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate keeps everyone honest—no matter how many years they’ve logged. Ignoring basic care cuts into both safety and the quality of scientific results. Nobody wants a surprise reaction or wasted research funding just because simple storage rules got ignored. Everyone wins when chemicals get put back on the shelf, closed tight, dated, and logged. Small steps save big problems down the line.

What Are We Really Handling?

1-Dodecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate pops up in labs working on ionic liquids, batteries, and sometimes even catalysis. These are jobs where a substance’s ability to conduct electricity, control temperature, or dissolve tricky compounds matters. So the name might sound intimidating, but the real question is: what sort of risk are workers or the environment getting saddled with?

Health Concerns: Not Just About a Scary Name

Most imidazolium-based ionic liquids like this one have extra-long carbon chains (that “dodecyl” part) and the tetrafluoroborate anion at the back end. Manufacturers and hazard data say not to eat it, breathe the powder, or get it in your eyes. The reason isn’t a vague allergy risk—studies, including those cited in journals like Chemosphere and Journal of Hazardous Materials, point to the real possibility of cell damage if exposed for long. Certain imidazolium liquids have shown cytotoxicity, which means they can mess with living cells. In high doses, the story gets worse: think possible damage to aquatic life, the risk of skin and eye irritation, and even potential changes in how your body’s nervous system works if enough gets into your bloodstream.

Some of these risk profiles came straight from accidental spills and lab mishaps. I’ve watched a graduate student get a splash of this class of compound on his hand, and even fast rinsing wasn’t enough to keep the red patch from itching for hours. Anyone handling powders or vials in a busy research lab knows that chemical gloves, goggles, and fume hoods aren’t just for show.

The Fluorine Factor: Worry for Water, Soil, and Air

Tetrafluoroborate is the part worth watching for long-term damage. Fluorinated anions can break down into persistent contaminants. If the compound gets into the water table, plants and microbes won’t just bounce back in a week. I’ve seen soil biology teams fretting over ionic liquid spills that killed the good bacteria they relied on for studies. Even if the breakdown rate is slow, the risk stacks up, especially with repeated exposure or poor waste disposal practices.

Regulation and Responsible Handling

This compound flies under the radar in a lot of places. Regulatory bodies like the European Chemicals Agency and the US EPA ask for careful documentation when handling new chemicals, but testing takes years. Manufacturers often sell 1-dodecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate under “industrial use only.” They provide safety data sheets with warnings, but not every buyer reads the full set of recommendations.

Biosafety officers in research settings highlight the need for real spill response kits, clear labeling, and chemical logs. We can make a dent in risks by offering open training, keeping inventories tight, and forcing take-back programs for unused chemicals. Disposal is best handled through trained waste contractors rather than tossed down the sink or into landfill—those persistent pollutants don't quit quietly.

Looking Forward

People innovate because new materials like ionic liquids promise better batteries or greener chemistry. But the benefits only stack up if we keep a step ahead of hazards, both for workers and the land outside the lab. Direct experience in a university chemistry building tells me that a safety shortcut today could cost years of cleanup tomorrow. Facts point to real harm if ignored, but a little vigilance helps us keep the risk in check while still reaching for breakthroughs.

What Purity Really Means in Chemical Research

In labs, purity isn’t a nicety—it’s a foundation. Scientists rely on pure chemicals like 1-Dodecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate to investigate reactions or engineer new materials. Manufacturers commonly reach purity levels above 97%, sometimes nudging over 99%. I’ve worked with enough specialty materials to know those extra percentage points matter. Contaminants turn up as noise in data or sabotage a reaction. I’ve seen a dozen projects stall or even fail from a hidden impurity, often traced to the careless use of low-purity ionic liquids.

The most reliable suppliers invest in high-precision synthesis and chromatography. An impurity can sneak in at almost any stage: starting materials, storage, even packaging. Trace water makes things worse, since materials like this imidazolium salt attract moisture. One time, a little unnoticed water made electrochemical readings swing by more than ten percent, wasting several weeks and budgets. Even in routine settings, purity gets checked by NMR, mass spectrometry, and ion chromatography. Fact is, no serious lab wants to cut corners here.

Why Molecular Weight isn’t Just a Number

Ask a chemist about molecular weight, and you get more than a tally of atoms. For 1-Dodecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, the average calculated molecular weight stands at 376.27 g/mol. Getting that number right isn’t busywork—it keeps volumes, reaction stoichiometry, and safety exact. In electrochemistry work, for example, miscalculating a molecular weight tweaks concentrations and messes with conductivity measurements. I remember prepping a batch assuming a wrong value from an outdated datasheet—every titration ended up off, and fixing the error meant redoing all prep and QA.

Complex molecules bring calculation risks. This one, with a dodecyl tail, two methyl groups, and the BF4 anion, rewards double-checking the math. Real experience taught me to always cross-reference several sources and never trust a single catalog value. Reputable chemical information databases standardize these values, but each lab batch should get a confirmation, especially for custom or small-batch synthesis.

Real-World Stakes for Purity and Weight

Researchers in green chemistry and battery science come across compounds like this every day. Ionic liquids influence outcomes in catalysis, separation, and electrochemical devices. At low purity, results start to fade or introduce false positives. These chemicals aren’t cheap, so every wrong order equals wasted dollars and lost time. Suppliers know reputations ride on these numbers.

Better transparency can fix a lot of headaches. Labs need suppliers who disclose not just product specs but also certificates of analysis—including test methods. Routine checks, like HPLC or Karl Fischer analysis for water content, should be the rule, not the exception. I’ve seen open communication between researcher and supplier catch errors before they become disasters, especially for ionic liquids prone to degrade with air or moisture exposure.

Steps Toward Fewer Pitfalls

Few labs have resources to check every bottle themselves. Standardizing third-party analysis, batch-specific documentation, and peer review by technical staff can catch issues early. Vendors offering regular updates make life easier. In my experience, ordering from well-reviewed companies pays for itself: products consistently hit their marked purity, people stand by their results, and technical support solves problems, not just recites catalog numbers. Selecting chemicals for demanding work never comes down to price alone—it’s about data, track records, and how much confidence I can put in every gram and every decimal place.

Understanding the Compound’s Place in the Lab

Many scientists working with ionic liquids have come across 1-dodecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate. Its name stands out, mostly because of the long hydrocarbon chain and bulky imidazolium ring, paired with a simple tetrafluoroborate anion. This specific combination shifts its behavior in solvents and opens up doors to creative chemistry. Looking at actual practice in the lab, solubility matters not just for calculations but for real breakthroughs, especially when people mix it with other chemicals or try to separate compounds.

What Dissolves It?

This ionic liquid prefers organic media more than water. The long dodecyl tail repels water, so you may shake a bit of it in a beaker, but the compound tends to clump up or float at the surface in pure water. Hydrophobic ionic liquids like this one dissolve better in non-polar or moderately polar solvents, where the dodecyl chain feels at home. If you pour acetonitrile, dichloromethane, chloroform, or even toluene onto it, you'll notice much better results. Researchers from the Journal of Physical Chemistry highlighted these properties in several studies. The tetrafluoroborate anion gives it a touch of polarity, but not enough to counteract the oily nature of the dodecyl tail.

Alcohols such as ethanol sometimes work, but results depend on temperature and how much ionic liquid you try to put in. Methanol fares even worse because its polarity fights against the hydrocarbon chain’s push for separation. Tetrahydrofuran (THF) offers a good middle ground. As someone who has tackled stubbornly hydrophobic samples, seeing a slick layer dissolve smoothly in THF feels like a small win.

Why Solubility Matters in Application

People rarely mix ionic liquids into plain water in a production setting. In my time working on extraction projects, using the wrong solvent means you might watch material float uselessly, rather than interacting with targets. Separation of metal ions, uptake of organics, or catalysis in organic synthesis all rest on whether the ionic liquid gets along with the chosen solvent. In some cases, a mismatch leads directly to pricey waste or failed reactions. With solvents like dichloromethane or acetonitrile, the dodecyl-imidazolium salt actually gets involved, grabbing hold of other molecules or mediating the transport of ions.

Addressing the Challenges

Careful solvent choice saves money and prevents headaches down the line. Before using any new ionic liquid, I run small-scale dissolution tests across a set of likely contenders. Students I worked with got surprised at how much energy goes into tracking down the right solvent ratio. Data from chemical suppliers often suggests a one-size-fits-all approach, but sticking to real-world experimentation makes the difference. Charting the solubility yourself or leaning on peer-reviewed solubility tables saves time. For those worried about toxicity or environmental regulations, swapping from chlorinated solvents to greener options like ethyl acetate deserves attention, though challenges exist.

Final Thoughts on Navigating Solubility

Solubility isn’t a side note—it's the first step for any lab working to unlock the true potential of 1-dodecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate. The everyday workhorse solvents like acetonitrile and THF usually offer a starting point. Tailoring choices to match the ionic liquid’s bulky, hydrophobic character avoids waste and leads to smoother, more successful reactions.