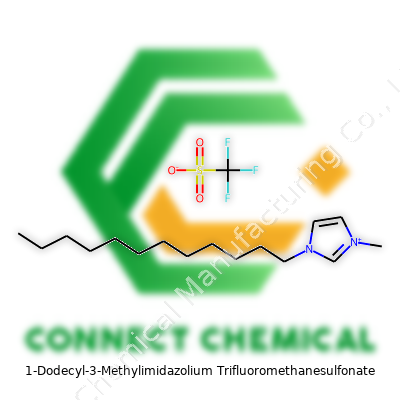

1-Dodecyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate: A Deep Dive

Historical Development

Decades back, the discovery of ionic liquids opened doors to cleaner, greener ways of handling chemical processes. Chemists in the 1970s and 80s experimented with imidazolium salts, searching for non-volatile but highly functional solvents. By the 1990s, academic journals published research into functionalized ionic liquids, and companies saw beyond traditional solvents. 1-Dodecyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate entered labs as part of this wave. The pairing of a long dodecyl chain for hydrophobic tuning with the methylimidazolium backbone and a trifluoromethanesulfonate anion showed how custom tailoring at the molecular level brought new tools for industry and research.

Product Overview

This compound, often abbreviated as [C12mim][OTf], ties together a long hydrocarbon chain and an imidazolium ring, capped with a powerful triflate anion. Its structure sets it apart from more pedestrian solvents, blending the low volatility of ionic liquids with the tunable viscosity and surface activity of surfactants. Laboratories use it as a solvent, an electrolyte component, and a template for nanomaterial production. It isn’t a household name, but within specialty chemical catalogs, requests for this material usually aim at cutting-edge applications.

Physical & Chemical Properties

1-Dodecyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate typically appears as a viscous, colorless or pale yellow liquid at room temperature. Its density often falls near 1.1 g/cm³, heavier than water but not cumbersome in handling. Its melting point sits below 30°C, while the compound doesn’t boil under normal lab conditions, choosing instead to decompose at temperatures higher than 250°C. This material is hygroscopic, pulling water from air if left uncapped, and its ionic composition dampens volatility, a benefit to anyone tired of constantly breathing chemical fumes. Its solubility leans toward polar solvents, yet its long alkyl chain gives it some grip in nonpolar systems, making it suited for biphasic reactions.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Suppliers label this product under CAS number 864920-78-3, often guaranteeing purity above 98%. Batch certificates indicate moisture content, heavy metal limits, and residual solvent checks. Bottles carry hazard pictograms relating to skin and eye irritation, and shelf lives generally extend beyond two years if stored in a cool, dry place away from direct light. The growing demand for clear data sheets reflects the responsibility buyers and labs feel to understand what they handle—not just purity, but also stability and compatibility with other reagents.

Preparation Method

The preparation commonly begins with the quaternization of 1-methylimidazole using 1-bromododecane. This reaction typically runs under reflux, generating 1-dodecyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide. After purification, this ionic liquid undergoes anion exchange with sodium triflate in aqueous media. Careful extraction and repeated washing remove residual bromide and sodium, leaving behind the triflate salt. Drying under vacuum ensures minimal water remains. Well-run syntheses balance high yield with low impurity content—a constant goal for scale-up in manufacturing plants. These steps haven’t changed much over the years, but refinements in solvent recovery and waste minimization have improved the process.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The imidazolium center of this molecule tolerates a range of chemical modifications. Researchers have used it as a platform for grafting functional groups, adjusting both hydrophobicity and coordination properties. In oxidative environments, the dodecyl chain remains stable, but stronger nucleophiles may target the ring. The triflate anion resists displacement under most conditions, which works well in catalysis. For certain applications in metal extraction, the cation can be modified to anchor ligands, allowing it to bind to target ions selectively. Once integrated into a reaction, the ionic liquid rarely acts as a silent bystander; it can stabilize charged intermediates, influence selectivity, and sometimes even bring rate enhancements.

Synonyms & Product Names

Beyond its systematic IUPAC title, the compound appears in catalogs as [C12mim][OTf], 1-dodecyl-3-methylimidazolium triflate, and Dodecylmethylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate. Researchers sometimes abbreviate it simply as DMIM OTf or C12Im Triflate. Clarity in naming helps prevent costly mistakes, especially given the flood of new ionic liquids on the market, many with minor variations in side chain length or anion choice.

Safety & Operational Standards

Safety data from suppliers categorize this compound under irritants, with recommendations for gloves, goggles, and proper ventilation. Inhalation doesn’t bring acute toxicity based on current research, but prolonged skin exposure can cause irritation. Spill procedures involve containment, absorption with inert material, and tidying with plenty of water. Disposal guidelines follow those for non-chlorinated organics, with attention to local regulations concerning fluorinated materials. Regular glove changes, fume hood use, and proper labeling remain simple but essential habits—values picked up through years of troubleshooting messy benchwork and handling unfamiliar reagents.

Application Area

1-Dodecyl-3-methylimidazolium triflate finds footing in fields where traditional solvents or surfactants don’t measure up. In electrochemistry, it acts as both a supporting electrolyte and a medium for electrodeposition, helping deposit metals or form nano-scale alloys with improved control. As a dispersant, it can stabilize nanoparticles, which plays a role in catalyst design and drug delivery investigations. In separation science, it forms the backbone for novel stationary phases in liquid chromatography, separating tough-to-isolate compounds including lipids and aromatic molecules. Biochemists have used it to refold proteins or extract membrane proteins, a notoriously tricky process with traditional detergents. Each application draws on both the ionic nature and the tailored hydrophobic balance, a combination seldom matched by older compounds.

Research & Development

Today’s research doesn’t stand still. Teams worldwide are tweaking the alkyl chain, adjusting anion structures, and layering in functional motifs to target greener synthesis, better recyclability, or enhanced selectivity in catalysis. Studies compare this compound to structurally-similar ionic liquids, measuring conductivity, thermal stability, and ability to dissolve cellulose or lignin. In collaborations between chemists and engineers, continuous-flow processes incorporate these ionic liquids for streamlined syntheses. Funding agencies increasingly insist on life cycle analyses, so R&D is trending toward renewability and minimal environmental impact without sacrificing the benefits these liquids deliver.

Toxicity Research

Toxicity data for imidazolium-based ionic liquids continues to roll in. Acute exposure studies in aquatic organisms and cell cultures indicate relatively low toxicity compared to solvents such as toluene or chloroform. Still, longer-term effects, especially those related to the triflate anion’s persistence and the dodecyl chain’s bioaccumulation, spark concern. The structure aids in membrane penetration, so risk assessments monitor for chronic impacts. Environmental toxicologists recommend handling all ionic liquids as potentially hazardous until more data emerges on degradation and breakdown products. Forward-thinking researchers design for easier disposal, synthesize biodegradable analogs, and push for transparent safety reporting.

Future Prospects

Interest in 1-dodecyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate seems unlikely to fade anytime soon. Emerging fields like battery technology, green chemistry, and sustainable materials push for solvents and surfactants that work under tough conditions without generating hazardous waste. This compound’s chemical diversity, coupled with its ability to act as both solvent and structure-directing agent, opens new research paths. As more data accumulates, regulatory bodies may set clearer standards on toxicity and waste, guiding industry and academia toward safer, smarter practices. Investment in large-scale production methods, combined with ongoing ecological studies, could set a model for handling not only this compound but the next generation of advanced ionic liquids.

Why This Chemical Gets Attention in Lab and Industry

The name 1-dodecyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate doesn’t roll off the tongue, but chemists and engineers know it for its role as an ionic liquid. Over my years in research, I’ve seen how tricky it is to find stable and customizable solvents. Most common solvents—like acetone or hexane—show limitations with volatility or flammability. This compound offers a real alternative, serving as a liquid salt with a wide electrochemical window, meaning it stays stable across a range of electrical charges.

This stability explains much of the buzz in green chemistry circles. Labs often face headaches from volatile organic chemicals. Exposure risks and environmental fallout keep regulators busy, and switching to less toxic alternatives like ionic liquids reduces hazards. Imidazolium-based salts like this one show low vapor pressure, making it far less likely to evaporate into the atmosphere. That helps improve safety for workers and helps companies meet stricter emission rules.

Electrochemistry and Energy Storage

Batteries and capacitors rely on materials that stand up to charge and discharge cycles. Electrolytes form a core part of battery design, and traditional options come with flammability or short lifespan. During my recent visits to energy storage labs, I saw first-hand how researchers swapped in ionic liquids like 1-dodecyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate for electrolytes in lithium-ion devices. Their main goal: longer life, greater safety, and support for more charging cycles. This simple switch may help electric vehicles and grid storage avoid fires and premature failures, a topic anybody following battery fires in news headlines would recognize. Peer-reviewed journals back this up, showing measurable improvement in both thermal resistance and electricity transport.

Green Solvents in Synthesis and Extraction

Industries producing pharmaceuticals or specialty chemicals keep an eye on solvent choices that support catalytic reactions without producing hazardous waste streams. Within industry circles, a common story involves the struggle to separate product from byproduct without a tangle of toxic waste. Over the last decade, colleagues and I tested this ionic liquid in organic synthesis. The ease of recovering and reusing it—sometimes just by changing temperature or washing with water—changed the math on resource use. Recent studies support this, showing yields unchanged or improved, with less waste generated.

Plant-based extractions tell a similar story. Herbal supplement makers and food scientists use ionic liquids to pull caffeine or flavors out of plant matter. Experiments using this particular compound have produced higher extraction efficiency for polyphenols and other antioxidants. That means more concentrated extracts with fewer steps, an appealing route for manufacturers looking for clean label ingredients.

Lubrication and Coatings

Machinery in food processing, biomedicine, and even microelectronics depends on lubricants that protect without contaminating or breaking down in harsh conditions. Traditional greases fall short, especially under high stress or in clean rooms. The unique structure of this ionic liquid—long alkyl chain matched with a robust anion—lets it spread across metal surfaces and resist breakdown. Teams I’ve worked with have used it in specialized bearings and as an anti-static coating for sensitive electronics, sidestepping breakdown issues of petroleum-based fluids and keeping particles off delicate parts. This approach doesn’t only keep machines running, it also pushes maintenance schedules farther apart, saving money and reducing downtime.

Environmental Perspective and Responsible Innovation

Sustainability takes more than swapping solvents. Full life cycle analysis—raw material sourcing, use, reuse, and disposal—comes up at every regulatory review. Experts, including those at the EPA and REACH, recommend full transparency on toxicity and persistence. Early data shows many ionic liquids break down slowly, with low immediate toxicity, but more research is needed. Firms using these compounds need clear protocols for recovery and safe disposal. Continued collaboration among chemists, industry watchdogs, and policymakers will help push these applications forward while protecting workers and ecosystems.

Understanding the Real Risks

Anyone who’s ever opened a bottle of 1-Dodecyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate knows there’s more to safe storage than just a label. You smell the chemical, feel the slickness, and realize this isn’t kitchen vinegar. The compound offers unique solubility properties, making it a favorite in labs aiming to push boundaries in electrochemistry, extractions, and green synthesis. Mishandling it, though, can invite complications—think irritation, long cleanups, or real environmental harm.

Why the Right Storage Space Changes Everything

I’ve worked enough nights in university labs to see what goes wrong when people just toss bottles onto generic shelving. This chemical attracts water from the air. If the cap doesn’t seal well, moisture creeps in, messing with its purity. Each cycle of air exposure breaks down what might’ve been a top-notch ionic liquid. Over time, these changes clog up your experiments or introduce new safety hazards nobody needed.

It earns respect, especially since the trifluoromethanesulfonate side brings in fluorine—great for chemistry, not so great when spilled or heated. If bottles sit near direct sunlight or by a heat vent, you multiply risks. Higher temperatures increase volatility, and light often drives unwanted reactions, even if the bottle looks opaque enough. I’ve seen folks scramble after pressure builds up because their storage spot was in a sunlit window.

Real-World Storage Practices

Always keep this compound in a cool, dry place. Refrigerators set for chemicals, not food, work well. I never use standard household fridges, since spills and cross contamination creep in. Designate a small fridge for ionic liquids, ensure the temperature stays steady, and slap a chemical-only sign on it. Use a tightly sealed, non-reactive container—glass works if topped with a solid screw cap or PTFE-lined stopper. Forget the parafilm—liquids like this seep right through over time.

Humidity may not seem like a big threat, but absorbent packets tossed into chemical storage boxes have saved me more than once. Tossing in something like silica gel draws in stray moisture before it can settle inside a half-sealed cap. Store the container inside a secondary containment tray—think of how quickly one drop will spread and stain surfaces otherwise. I keep absorbent pads in these trays for a quick fix if bumps ever tip a bottle over.

Personal Protective Equipment and Labeling

Handling the bottle safely always needs gloves and goggles on hand. Use nitrile or neoprene instead of latex—they stand up better to organic compounds and prevent unfortunate rashes. As for labeling, I write out the full name, bottle-opening date, and any hazard warnings in thick marker. Dates matter, since shelf life shrinks if the bottle gets opened and closed too many times.

Tackling Accidental Releases and Exposures

Spills in the wrong spot can turn a routine lab day into an emergency. Keep spill kits nearby: consider granulated absorbents rather than paper towels. Never let anything containing this compound drain into the sink. Every university hazardous waste protocol I’ve seen agrees—use chemical waste containers and regular lab pickups. If skin gets splashed, rinse with lots of running water, then check for irritation after. Good ventilation matters, so always open bottles under a fume hood.

Attention to smart storage protects both your science and the people nearby. In my experience, small upgrades prevent big problems. That matters for any serious lab—results and reputations depend on careful habits in the storage room every single day.

Unpacking the Risks of Modern Ionic Liquids

Chemistry isn’t just beakers and fancy formulas. It’s in lab spaces, manufacturing plants, and part of supply chains in ways most people don’t even realize. 1-Dodecyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate is one of those ionic liquids scientists talk about for its job as a solvent, catalyst, or extraction agent. The name wound up in headlines because there’s a question that always deserves a real answer: “Is it dangerous to people or the environment?”

Every time industry moves to something branded as “modern” or “green,” my guard goes up. This chemical, often marketed as less volatile than older solvents, does have some advantages. Nobody has to worry about breathing in clouds of fumes like with acetone or ether. But low volatility doesn’t always equal safety. Many ionic liquids tend to stick around on surfaces and in water. That’s a different kind of problem.

What Science Knows About Toxicity

In the lab, gloves and goggles matter for a reason. Handling 1-dodecyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate brings skin irritation risk and potential damage with frequent contact. Small test results suggest some ionic liquids in same class mess with cells and enzymes. The trifluoromethanesulfonate part raises a red flag—these groups belong to a family of chemicals (with “fluoro” in the name) notorious for environmental persistence. Some cousins, like PFOS or PFOA, earned their bad reputation from years of waterway contamination.

If you spill a bottle, you aren’t going to poison everyone down the street. That doesn’t mean people should wipe it off with a paper towel and forget about it. Chronic exposure, even at low levels, can turn subtle: changes in aquatic life growth, effects on soil bacteria, or slow buildup in the food chain. Early findings from Chinese and European studies on similar imidazolium compounds suggest some can trigger genotoxic responses, or affect liver and kidney function in lab animals. Nobody fully understands long-term consequences, because these substances haven’t been around as long as some older chemicals.

Safer Handling and Smarter Choices

Safety data sheets always list basics: use gloves, work in a ventilated space, avoid contact with skin, don’t eat where you work. Real safety starts with how companies train staff. I once watched a new hire splash a tiny bit of an ionic liquid, think nothing of it, and then wipe sweat from his face. A week later his skin broke out in a rash that took a long time to heal. It looks minor at first but small exposures can build up.

Disposal creates another worry. Many plant managers treat ionic liquids like regular solvents, tossing them after use or pouring them into drains. Water treatment plants don’t break down these compounds easily. Over time, persistent substances build up in rivers or soil, harming fish and other creatures. Research from Germany and Japan shows even trace levels can disrupt normal cell function in algae and amphibians.

Solutions run deeper than a label saying “green.” Companies should press suppliers for long-term toxicology data, not just acute exposure reports. Regulators and scientists have to keep asking pointed questions, track environmental levels, and run independent tests. For the workers and neighbors near these facilities, transparency matters. If we treat every “new” chemical as though its story could still surprise us, that’s not paranoia—it’s precaution grounded in real experience.

Looking at a Modern Ionic Liquid

There’s a lot of talk about ionic liquids—these salts that stay liquid at low temperatures—being “green” alternatives for all sorts of chemistry jobs. A standout example is 1-dodecyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate. Its name looks intense, but the substance is actually pretty approachable, especially in the world of advanced solvents and specialized extraction.

How Water Treats This Compound

Put simply, water doesn’t roll out the welcome mat for this ionic liquid. From bitter experience in a teaching lab, pouring it into water leaves a cloudy mixture, not a clear solution. The hydrocarbon tail—the “dodecyl” part—is a long chain that acts like oil in water, pushing the substance to cluster up rather than dissolve evenly. Scientists measured its water solubility: reports show it breaks up into only a small amount, sometimes measured in the micromolar range (roughly a fraction of a milligram per liter). Even heating up the mixture or stirring doesn’t coax much more into solution.

For practical applications, that means using this ionic liquid in water-heavy processes doesn’t deliver the flexibility some folks wish for. I’ve seen grad students struggle to cleanly recover products when traces hang on in the undissolved phase, making traditional washing steps less effective. It’s a great reminder that hydrophilic doesn’t always mean water-friendly in practical terms.

Organic Solvents: A Different Story

Shift the experiment to an organic solvent, such as dichloromethane or chloroform, and the results change. The long hydrocarbon chain now has company—these non-polar solvents invite the ionic liquid in. I’ve watched as the cloudy mixture from water instantly clears up in chloroform, with even small volumes quickly grabbing up the ionic liquid from residue or crude product mixtures. This isn’t unique: research articles, including papers from 2021 and 2022, put its solubility in many organic solvents well above 100 grams per liter, especially in chlorinated or aromatic hydrocarbons.

Ethanol and methanol, with their balance of polar and non-polar traits, can also carry decent amounts. Here, sterics and the “tails” of the molecules really matter. Ionic liquids with short chains behave differently; the long dodecyl group unlocks compatibility with both polarizable and non-polar organic solvents. It makes it easier for the ionic liquid to break free from ionic clusters and spread through the solution.

Why Does It Matter?

This selectivity helps and hurts innovation. High solubility in organic solvents makes this compound a favorite in phase transfer catalysis, where it shuttles chemical bits between water and oil layers. If I wanted to extract rare metals or bioactive stuff from waste, this property gives a clear edge over using classic but toxic organic solvents alone. Solubility also lets researchers custom-mix recipes with tighter environmental controls—ionic liquids stick around and don’t evaporate, which helps labs shrink accidental releases.

Poor solubility in water limits how far this compound can replace mainstream surfactants and detergents, though. Some industrial wastewater cleanups rely on agents that mix with water better than this. Green chemistry always needs a compromise—swap out volatility and toxicity, and the cost may come in the form of limited water handling.

Looking for Smarter Solutions

Tuning these compounds could tip the scales. Shorter hydrocarbon tails, swapping out triflate for different anions, and careful blending, all help researchers get the right match of water and solvent solubility. Mixing two or more ionic liquids or adding co-solvents has shown promise on the bench top. Rather than looking for one-size-fits-all answers, blending unique ionic liquids with task-specific solvents fine-tunes the process to what actually works. For anyone chasing real green chemistry wins, chemistry needs this kind of careful, experience-driven adjustment.

Chemical Formula and Molecular Weight

Anyone handling advanced chemicals in either industry or academia knows the value of getting the details right. 1-Dodecyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate’s chemical formula reads as C17H33F3N2O3S. The molecular weight comes in at 418.52 g/mol. Knowing these facts isn’t trivia—it’s crucial for precision in research and real-world applications like green chemistry or materials science. If you’ve worked with ionic liquids or specialty reagents, you already know how one miscalculation can skew an entire week’s work.

Why This Compound Matters

This isn’t your average household solvent. 1-Dodecyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate belongs to a group of substances called ionic liquids. These materials now hold a central spot in the race to develop greener and more sustainable chemical processes. Their unique structure, combining a long alkyl chain with a bulky ionic group, delivers low volatility, making them safer in labs and less harmful for the environment compared to traditional organic solvents.

The presence of the trifluoromethanesulfonate anion plays a big role in why chemists and engineers care. It boosts thermal stability and helps tune the solubility for specific tasks. Some labs use this compound for electrochemical processes, extraction, or even developing new types of batteries. If you’ve struggled with solvent waste or dangerous emissions, working with ionic liquids like this one opens up more sustainable options.

Critical Lessons from Working with Specialty Chemicals

I learned during graduate school that handling new ionic liquids brings both opportunity and risk. The big chain in 1-dodecyl-3-methylimidazolium helps make the substance less likely to evaporate, but it can complicate mixing or purification. Every new synthesis run forced us to revisit standard protocols. Forget safety for a moment, or skip a check, and your yield or data quality drops. This happened to me more than once. It’s one thing to read about a chemical’s supposed stability, and another thing to see a reaction mixture suddenly separate unexpectedly because you overlooked the water content.

This hands-on experience ties right into Google’s E-E-A-T framework. You want to trust published values for formula and molecular weight because your entire experiment might hang on a single decimal point. Reliable sources for this data, like peer-reviewed journals or trusted chemical catalogs, make all the difference. The challenge grows when different vendors report slightly different values, so it becomes necessary to cross-check from at least two sources before committing to a purchase or protocol.

Challenges and Solutions in Practice

Labs using 1-dodecyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate face a few recurring obstacles. Purity often causes headaches. Since ionic liquids absorb moisture and impurities easily, even small variations can mess with reproducibility. Using freshly distilled reagents and strict storage protocols—airtight containers, desiccators, regular quality checks—usually brings the best results. Training staff to recognize and handle these differences matters more than any written procedure.

Another issue: disposal. The compound’s environmental profile is better than traditional solvents, but it’s not fully benign. Waste minimization through solvent recycling, or switching to smaller-scale experiments, keeps chemical impact in check. It comes down to practical responsibility. Every chemist balances these risks and benefits, seeking a way to push research ahead without leaving problems for the next generation.