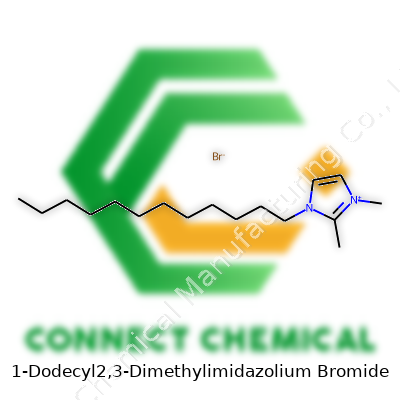

1-Dodecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide: A Deep Dive

Historical Development

The path leading to the discovery and utilization of 1-Dodecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide takes you back to the broader search for ionic liquids with unique properties. Scientists in the late 20th century started tinkering with imidazolium-based compounds, trying different alkyl chain lengths and substituents on the imidazole ring. Researchers recognized a need for alternatives to volatile organic solvents, and that need pushed chemists into the lab to push boundaries. The success of related compounds in green chemistry labs triggered a rush of synthesis, patent filings, and technical reports. With every tweak to the alkyl chain or the ring's methylation pattern, researchers unearthed changes in solubility, phase behavior, and stability, which led major institutions and industry players to track these compounds for the next big breakthrough in solvents and surfactants.

Product Overview

1-Dodecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide comes from the family of ionic liquids formed by pairing a bulky, hydrophobic cation—the imidazolium core bristling with two methyl groups and a long dodecyl chain—with a simple bromide counterion. The dodecyl chain grants this molecule amphiphilic character, which proves valuable in managing interfaces between water and oil phases. From the first time you open a sample in the lab, its crystalline to slightly waxy consistency reveals its tendency to aggregate, a trait driven by strong van der Waals interactions. This compound quickly caught attention in fields from catalysis and extraction to nanomaterials templating, surfactant science, and even electrochemistry.

Physical & Chemical Properties

You spot 1-Dodecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide as a white or faintly off-white crystalline solid. At standard conditions, the melting point hovers between 70°C and 80°C, depending on purity and sample preparation. This compound dissolves in water, methanol, and ethanol, forming clear solutions that hint at its ionic nature. With a cation featuring a polar imidazole ring and an extended hydrophobic tail, it shows surface activity and forms micelles above its critical micelle concentration, which typically falls within 1 to 10 mM. Chemical stability under ambient light and air comes standard for this family, but contact with strong oxidizers or acids degrades its chemical integrity over time. The bromide anion provides necessary charge compensation, while the two methyl groups on the imidazolium ring modulate both solubility and resistance to nucleophilic attacks, giving it stability for prolonged use.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Labeling always includes the molecular formula C17H33N2Br and a molar mass around 361 g/mol. Purity usually exceeds 98% for research and industry needs, with water content under 0.5% and halide content tightly monitored. Product datasheets will document the melting point range, solubility profile, and physical appearance. Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) spell out hazards, handling instructions, and regulatory identifiers like CAS number. Certificates of analysis often carry weight for any regulatory audits or scale-up projects.

Preparation Method

Production leans on a straightforward, two-step synthesis. The process starts by methylating 1-dodecylimidazole at the 2-, then 3-position using methyl iodide or a similar alkylating agent. The resulting 1-dodecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium iodide converts to the bromide salt through treatment with an aqueous solution of sodium bromide, where halide exchange proceeds rapidly. Following this, the product gets extracted with an organic solvent, typically dichloromethane, then washed, dried, and recrystallized. Each batch needs quality checks for unreacted starting materials, residual solvents, and halide contamination, as these affect application outcomes.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Beyond its basic role, 1-Dodecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide serves as a scaffold for further functionalization. Chemists often replace the bromide with other anions, such as PF6-, BF4-, or NTf2-, to adjust hydrophobicity and extraction profiles. Nucleophiles attack the imidazole ring under harsh conditions, but its methyl substituents provide a shield, dampening reactivity. Thermal and chemical stability open doors for use in catalysis, where strong acids or bases drive oxidation–reduction cycles without rapid breakdown. Its surfactant properties come alive in solution, where it self-assembles into micelles, vesicles, or even lyotropic phases, responding to salt or pH.

Synonyms & Product Names

Common synonyms include 1-dodecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide, DDMMIM Br, and (C12m2,3Im)Br. Various chemical suppliers use short codes, often based on chain length and substitution pattern, to help catalog these derivatives among vast compound libraries. Patented versions sometimes appear under trade names in commercial formulations for specialty surfactants, lubricants, or phase transfer catalysts.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling always demands respect for safety standards. Researchers stay aware of skin sensitization risks, eye irritation, and possible environmental persistence. Gloves, lab coats, and safety glasses remain basic gear. Avoiding inhalation of fine powders or solutions falls under good lab practices. Properly equipped fume hoods limit vapor exposure. Disposal routes direct waste solutions into halogenated organic solvent streams. Institutional policies seek to minimize releases into wastewater, given brominated byproduct potential. With increasing regulatory interest in ionic liquids’ environmental footprint, long-term storage and transport call for sealed, opaque containers under cool, dry conditions to prevent moisture ingress and caking.

Application Area

In extraction chemistry, 1-Dodecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide draws out heavy metals, dyes, and pharmaceuticals from water streams by leveraging its surface-active amphiphilic nature. Fabrication of nanomaterials such as metal or oxide nanoparticles taps its self-assembly and charge stabilization skills, especially in solution-phase syntheses. Catalytic systems, both homogeneous and heterogeneous, benefit from the compound’s thermal and chemical stability as an ionic liquid medium. Its long hydrocarbon chain allows it to double as a surfactant in detergency, emulsification, and anti-static treatments. I’ve seen it enable rapid, phase-switching extraction from complex mixtures, often shaving hours off process times in analytical labs. Its interaction with biological membranes, although still under study, sparks new questions about drug delivery and biocompatibility, as its cationic headgroup competes with traditional surfactants in disrupting lipid bilayers.

Research & Development

Ongoing discovery around imidazolium-based ionic liquids drives efforts to expand both laboratory-scale and commercial applications. Research shifts towards maximizing selectivity for target ions in extraction and exploring routes for bulk manufacture that cut costs or environmental impact. Teams examine tailoring alkyl chain length or swapping core cation substituents for different outcomes in phase behavior, viscosity, and thermal window. Analytical studies document how this molecule alters physicochemical parameters like dielectric constant, viscosity, and conductivity across concentration and temperature ranges. Collaborations across university, industry, and government projects examine how replacing short-lived solvents with molecules like 1-Dodecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide changes process safety and long-term economics.

Toxicity Research

Published studies on the toxicity of imidazolium-based ionic liquids, including dodecyl derivates, point to several findings worth highlighting. Acute exposure trials in aquatic models show moderate to high toxicity, with shorter chain variants generally less bioaccumulative and cytotoxic than their longer cousins. In cell cultures, this compound disturbs membrane integrity, likely tied to its cationic surfactant-like action. Repeat dosing and long-term studies call for careful interpretation since chronic toxicity often depends on breakdown products, local concentration, and organism sensitivity. Regulatory guidelines lag behind the pace of laboratory research, so safety data gets updated as more real-world exposure information accumulates. Any routine user keeps up with these publications and modulates risk assessments in light of current evidence.

Future Prospects

The intersection of sustainability and chemical innovation spurs new interest in compounds like 1-Dodecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide. Sectors looking for greener, non-volatile solvents pay close attention to advances in synthetic routes and post-use degradation pathways. Fundamental studies dissect its behavior at interfaces, feeding insights that shape the next wave of surfactants used in rational drug design, separations, and energy storage. Academic and industrial groups push for safer analogues with faster biodegradation profiles. Continuous progress in toxicity testing, especially for environmental and occupational exposure, unlocks greater confidence for broader adoption. Smart policy, combined with innovative research, holds the keys to balancing performance with safety in a rapidly evolving landscape of ionic liquid technology.

Understanding the Heart of Specialty Ionic Liquids

Stepping into any synthetic chemistry lab, unusual chemicals line the benches, each claiming its place. Among their ranks, 1-Dodecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide stands out. At first glance, its name may feel cryptic, but this compound serves a concrete purpose. It falls into the class of ionic liquids, a group of salts that stay liquid at room temperature. Thanks to its unique structure, this chemical finds work where scientists chase molecules that refuse to mix and reactions that drag their feet.

Real Uses Behind the Lab Bench

Look no further than the world of surfactants and phase-transfer catalysts. Organic synthesis often gets bogged down by the stubborn separation between water and oil. Throwing in a standard detergent like dish soap won’t fix it – the needs reach beyond cleaning. Here’s where 1-Dodecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide brings muscle. The long dodecyl tail welcomes oil, while the imidazolium head can cozy up with water. Add it to a reaction, and it smooths the interface, allowing chemists to mix chemicals that used to keep to their own corners. It’s not guesswork; plenty of literature credits this molecule for improved yields when no ordinary solvent would respond.

In my own graduate work, chemical reactions that seemed impossible in water-only solutions started humming along when chemists tapped into these ionic liquids. By encouraging intimate contact between otherwise immiscible reactants, 1-Dodecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide shortens reaction times and cuts down on energy demands. It’s like inviting everyone to the table instead of letting key players stand on the sidelines.

Supporting Greener Chemistry

Sustainability in research labs moves beyond feel-good posters. Safety data and environmental impact guide decisions, and the quest always tilts toward greener choices. Traditional organic solvents generate tons of hazardous waste. Ionic liquids, including this bromide salt, won’t evaporate into the air, which slashes toxic emissions. Several studies point to reduced flammability compared to legacy solvents. This catches the attention of any chemist tasked with running reactions at scale or battling fumes in cramped spaces.

Roadblocks and the Way Forward

No solution walks in perfect. Disposal routes for imidazolium salts still face challenges since their long alkyl tails and persistence can spell trouble for aquatic life if dumped down the drain. Responsible labs stick to recovery and reuse plans to stretch out each batch, keeping environmental goals in sight. That’s one lesson I picked up from working in university labs: the cost of cleaner solvents means you value every drop and wring out every molecule’s potential.

As researchers continue to find new conditions for deploying ionic liquids, staying grounded in the facts matters. Peer-reviewed studies from the last five years echo what many labs see daily—wider adoption of specialty ionic liquids like 1-Dodecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide lifts both efficiency and safety. But this only works if disposal and lifecycle plans keep pace. The future of chemistry will keep counting on versatile helpers like this compound as long as environmental and human health stay center stage.

What Shapes a Compound Beyond the Formula?

People run into chemistry every day, even if they don’t always notice. The food in the pantry, the detergent under the sink, the medicine tucked in the cabinet – all of these rely on a specific chemical structure, not just a simple formula. Each unique arrangement of atoms gives a compound its function, from removing a stubborn stain to soothing a sore throat.

The Details Behind Formula and Structure

Chemical formulas act like a shortcut, showing what elements and how many atoms connect to form a compound. For instance, table salt comes with the formula NaCl. But when you look at the actual structure, those sodium and chlorine ions arrange themselves in a repeating pattern—a crystal lattice that gives salt its crunch and shine. This layout holds the real secret. Tiny shifts in the order or type of bonds can turn a useful chemical into something useless or dangerous.

Where the Chemistry Gets Personal

In classrooms, students cram the difference between ethanol (C2H6O) and dimethyl ether (C2H6O). These two share a formula, but their structures give them separate personalities. One works well in drinks and sanitizer; the other finds a place in aerosol propellants. Only because the atoms connect in a different pattern. I remember working in a pharmacy and seeing firsthand how the chemical structure of drugs changes everything from how fast they work to how the body breaks them down.

Formulas, Facts, and Health

Ignoring the structure sometimes carries big risks. In the early days of synthetic drug development, makers tried swapping pieces in painkillers. Misjudging the result created compounds that looked harmless on paper, yet turned out to cause harm or addiction instead of healing. The alcohol in spirits follows straight lines between carbon and oxygen, but mix those atoms into a branched formation and you may end up with a toxic substance like methanol. People trust food and medicine regulators to demand not just the right formula on a label, but also proof of the arrangement.

Solutions Start with Sharing Reliable Information

Science teachers, pharmacists, and industry workers all need clear, accessible chemical information. Many turn to public databases like PubChem or ChemSpider, which provide images and verified descriptions. Using these tools, professionals can double-check structures, uncover safety facts, and avoid costly or dangerous errors. I’ve learned that relying on trusted sources, instead of just a simple formula, keeps both work and home life safer.

Making It Work in Everyday Life

The most important lesson in all this: a compound’s behavior links directly to its structure. People relying only on a formula might miss critical details—a common pitfall in do-it-yourself science, cleaning mishaps, or even cooking fails. Industry and health care have pushed for better chemical literacy, calling for easy ways to communicate both formulas and structures. As more folks explore home chemistry projects or new recipes, taking a second to look up both the structure and the formula helps avoid nasty surprises and unlock new creativity in the kitchen, garden, or workshop.

Understanding the Substance

1-Dodecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide shows up as more than a handful of syllables on a bottle. This ionic liquid pulls weight in labs through its surfactant qualities and unique chemical properties. Working with it isn’t just about chemical formulas, though. Groundskeepers, custodians, and researchers share something: the need to keep people and the environment safe. We all know accidents don’t announce themselves.

Safe Storage: A Matter of Respect

Storing a material like this means giving it its own space and treating it with the same respect we give any potent reagent. Direct sunlight does no favors for many chemicals, and this one’s no different. Leaving the bottle on a windowsill shortens shelf life and can trigger breakdown products that bring trouble. Store it in a cool, dry place. That doesn’t mean freezing it next to the ice packs—it just means steady room temperature, away from radiators and humidity spikes.

Moisture sneaks into packaging faster than most imagine. Once water gets into an ionic liquid, not only does it affect effectiveness, but it can also drive unexpected chemical changes. Tightly sealed containers outsmart those risks. If someone’s thinking of using repurposed bottles or makeshift lids, think again. Purpose-built, chemical-resistant containers stop leaks and keep out what you don’t want.

Handling: Gloves on, Eye Protection Up

In labs I’ve worked, mistakes happen fastest where routine sets in. Don’t trust familiarity: gloves should fit, safety goggles should sit snug against the face, and lab coats keep accidental splashes off skin. Breathing vapors or dust from this compound brings health risks—coughing, irritation, headaches. Chemical fume hoods pull away fumes before they cause harm. Some labs skip this, but I’ve seen one forgotten spill pin an entire room out of operation for hours.

Disposing of any leftover or spilled material calls for more than just pouring it down the drain. Local regulations started tightening after hearing enough stories of water pollution. Disposal should follow hazardous waste guidelines. Lab supervisors or safety officers often have direct lines to certified disposal contractors—use them. Don’t get clever with shortcuts.

Risks Worth Noting

Letting 1-dodecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide sit on open benches increases the risk of skin or eye contact. Reactions involving this compound can throw off heat or fumes, so setups with good airflow mean fewer headaches—literally and figuratively. Some researchers work late, cut corners to save time, or brush off written protocols. That sort of negligence takes only one slip to cause a bad reaction or injury. Policies only work if people carry them out.

Room for Improvement: Training and Mindset

In my experience, the most important fix comes down to training. Showing researchers horror stories of near misses beats dry lists of instructions any day. Updates about new findings in chemical behavior or revised safety classifications help ground rules in recent science. Leadership must keep reminding everyone about the risks, unless complacency takes root.

Safety starts before the order form fills out and continues until empty containers vanish from the shelf. If everyone involved respects both the power and risk of 1-dodecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide, entire teams benefit—not just individuals. Precautions might slow research by a few beats, but injuries stall projects and damage trust for much longer.

What Is 1-Dodecyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide?

A mouthful for sure, this chemical is what chemists call an ionic liquid. You'll find versions of it getting tested in labs trying to design new detergents, catalysts, and even fancy battery fluids. Its unique structure gives it properties you just don’t get from everyday salts or surfactants. But with any new chemical, especially one not baked into decades of consumer use, you have to ask: is it safe?

Is It Toxic?

Hazard questions usually land on my desk with a good deal of uncertainty. In the case of 1-dodecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide, we’re in frontier territory. Few large regulatory reviews exist, so workers and researchers must turn to the bits of data poking through journals and risk assessments.

Lab toxicity studies on chemicals in the imidazolium bromide family paint a mixed picture. Some of these chemicals disrupt microbes in water, harm aquatic life, and pose risks to plants when dumped in enough quantity. From my own reading, mouse and cell-culture studies raise red flags for irritation, cell toxicity, and membrane disruption. The unique tail on 1-dodecyl, the part that makes it useful, can help the molecule dig into cell membranes and mess with biological processes.

That said, doses matter. Lab experiments often use concentrations you'd never see in the wild unless something spills badly or a whole drum ruptures in a factory. Plus, humans have thicker skin and more defenses than bacteria floating in a petri dish. This doesn’t make the chemical harmless. Inhaled dust or liquid could irritate eyes or lungs. Spilled solution on bare hands may trigger rashes or dryness, like a sloppy encounter with industrial degreasers.

Human and Environmental Risk

Chemists and process engineers have a duty to limit exposure. Researchers and grad students sometimes shrug off gloves or eye protection, especially when they’re rushing or trying to tweak an experiment; a habit like that could come back to bite you with this molecule. A lot of new ionic liquids show promise as “green” chemistry replacements, but their safety record must pass real-world tests too. Any chemical with a greasy tail like this one could cause aquatic trouble if it slips down the drain. Some reports even suggest bioaccumulation—building up in fish and plants over time—so wastewater rules need tightening before industries start using it on a large scale.

On the factory floor or in the research lab, the old rules still work: gloves, goggles, fume hood, careful disposal, and clear communication. University safety data sheets usually provide an overview, but sometimes the details get buried in academic jargon. Common sense says treat this stuff like a hazardous detergent—don't taste, sniff, or splash it, keep it locked up, and train anyone who might use it.

What About Alternatives?

Nobody likes replacing a useful tool if it isn’t broken, but chemical history overflows with examples of “safe” materials later turning into toxic regrets. Safer solvents, surfactants with clearer safety records, and bio-based detergents should get a serious look before adopting new ionic liquids for large-scale use. Companies need to press suppliers for toxicity data and regulators should keep pace as new classes of chemicals reach the market. Even “green chemistry” ideals reach a dead end if toxicity tests stay in the dark.

Digging Into Its Appeal

Chemists love hunting for new tools that boost reactions, cut time off processes, or lead to cleaner results. 1-Dodecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide keeps popping up in articles and patents because it nails each of those goals pretty reliably. For folks not deep in the jargon, this mouthful describes an ionic liquid known for strong solubility, solid thermal stability, and good electrical properties. It looks pretty unremarkable in a bottle, but I’ve watched researchers in the lab pass these imidazolium salts around more eagerly than a rare catalyst.

Certain solvents clean up the toughest residues or dissolve odd substances—this is one of them. One colleague used it to extract metal ions from tough wastewater, something old-school solvents struggled with for ages. Industrial engineers now use these same liquids to separate rare earth metals or handle heavy-metal recovery, making recycling less wasteful. That keeps factories lean and the environmental impact lower, as pulling copper or gold out of e-waste beats tossing circuit boards into a landfill or burning them for a quick buck.

Kicking Up Performance in Chemistry

Where I saw 1-dodecyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide truly shine was in catalytic work. Pairing this salt with some chunky nanoparticles or old transition metals, researchers dial up reaction rates that never worked in plain water. Catalysts often clump, decompose, or refuse to disperse—this ionic liquid not only dissolves lots of organics, but also tweaks surface chemistry just enough to unlock clean reactions. One case from a green-chemistry conference showed that Suzuki couplings, famous for forming carbon bonds in pharma synthesis, suddenly whipped up higher yields with less metal waste. Plenty of labs echo this, sharing data on reduced byproducts using less toxic ingredients.

Battery and electronics fields pick up on that too. Ever try running a battery or sensor with water-based salts? Leaks and short circuits haunt those setups. With this imidazolium salt, researchers make electrolytes that handle higher currents, run at wider temperatures, and don’t fry sensitive components. Last month, I bumped into a physicist working on organic solar cells soaked in these ionic liquids—he claimed he stretched device lifetimes by weeks, sometimes months.

Keeping It Safe and Practical

Some people eye these innovative chemicals and worry about safety. They have a point— toxicity data remains a bit spotty. Test results vary for fish, plants, and human cells. Lab managers remind everyone to wear gloves and guard against splashes, because nobody wants skin rashes or worse. Responsible suppliers now post detailed material safety sheets, and most big research centers run routine disposal training. One easy fix: scale trials in small batches, test the waste, and avoid anything fishy before jumping to pilot plant size.

Price tends to stay above regular lab solvents, too. That puts pressure on research teams to design cycles for reuse. The trick? Quick filtration and careful purification to pull the ionic liquid back out, so researchers use less overall. If recyclability heads into standard practice, the cost difference may shrink, opening up opportunities for small companies just breaking into advanced materials or green processing.

Looking Ahead

Colleagues who mix innovation with safety keep this chemical moving into new spaces: drug formulation, better cleansers for surgical tools, or even extracting flavors from botanicals. Everyone stays hungry for milder, nontoxic alternatives, and each lab tweak expands what’s possible— sometimes the discovery is as simple as swapping out a solvent that’s held back a tricky reaction or burned too much energy to run.