1-Dodecylpyridinium Bromide: Insightful Commentary on a Niche Compound

Historical Development

Chemistry moves forward step by step, often fueled by the curiosity of scientists tinkering at the edges of what people already know. 1-Dodecylpyridinium bromide, although not a household name, entered the scientific conversation in the 20th century as researchers pushed further into the properties of surfactants and quaternary ammonium compounds. The roots of this compound trace back to efforts to control microbes and manage cleanliness in environments where bacteria run rampant. Its place among amphiphilic molecules makes it valuable in labs exploring how detergents, antiseptics, and specialty chemicals shape human interaction with invisible threats. In my reading, early patents and journal notes from the 1950s and 1960s highlight a slow ramp-up from curiosity about antimicrobial activity toward practical application. Such transitions require balancing efficacy, safety, and economic realities—never a simple equation.

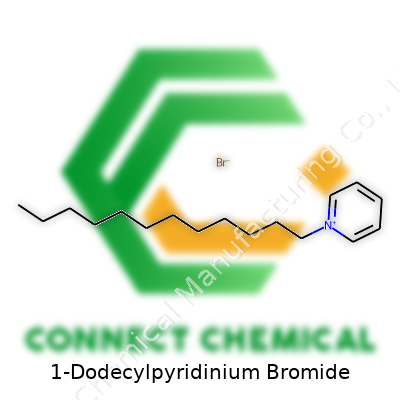

Product Overview

In chemical supply catalogs, 1-Dodecylpyridinium bromide appears as a white crystalline powder, often stored in airtight containers to guard against moisture. The product reaches consumers ranging from university chemists to private researchers, sometimes in modest bottles, sometimes ordered in bulk by specialty manufacturers. What stands out is its dual role: cleaning agent and research tool. Lab workers depend on it for experiments examining membrane disruption or colloid stabilization. Some see it as a quirky cousin to more common quats, but those who know its profile find a range of uses that simpler surfactants can’t always match.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Looking closely at its makeup, 1-Dodecylpyridinium bromide has the formula C17H30BrN and a molecular mass hovering around 344.33 g/mol. The compound features a 12-carbon alkyl tail—a key element for surface activity—stitched onto a pyridinium ring, paired with a bromide counterion. The result is solid at room temperature and readily dissolves in water and certain organic solvents. Anyone who’s tried to dissolve it notices how the long alkyl chain creates thick solutions at higher concentrations, a property exploited in micelle formation. This combination of hydrophobic and hydrophilic portions offers a seat at the table for discussions about emulsification and biological disruption.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Suppliers rarely skimp on details: technical data sheets offer melting points around 180°C, high purity (above 98%), and warnings about light sensitivity. Labels spell out hazard classifications—irritant to eyes and skin, respiratory effects if misused, environmental warning where aquatic life faces risk. Batch numbers, storage instructions, and expiration dates all make it easier to track quality and ensure reactions proceed as planned. These details matter. More than once, a colleague in the lab wrestled with an off-label bottle, never realizing an expired or degraded surfactant was skewing their results.

Preparation Method

Getting to a usable batch involves quaternization—the process where lauryl chloride reacts with pyridine under controlled conditions, followed by introduction of bromide ions. This sounds straightforward, but anyone who’s tackled the process at scale faces headaches around purity control and waste management. Recrystallization becomes necessary to wash out impurities, and even small slip-ups with temperature or solvent ratios can spoil a batch. Factories use specialized glass or stainless steel reactors to handle the corrosive properties during synthesis, and purification steps include careful filtration and drying.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

This compound doesn’t rest easy on the shelf. In the lab, chemists exploit the reactive pyridinium ring and long alkyl chain to form derivatives with tailored properties. I’ve seen studies where teams swap the bromide ion for chloride or tweak the alkyl tail length to adjust detergent effectiveness or toxicity. Reductive reactions can modify the pyridinium to unleash new functionalities, while alkylation or arylation at different positions yields whole new classes of amphiphiles. With these modifications, the door opens to applications in catalysis, analytical chemistry, or as probes for biological membranes.

Synonyms & Product Names

The language of chemistry favors clarity and confusion in equal measure. 1-Dodecylpyridinium bromide appears under names such as N-Dodecylpyridinium bromide or Laurylpyridinium bromide; less often, someone refers to it by a trade name or a catalog code from major suppliers. Mischief comes when abbreviations like DPBr or DDPB pop up in publications, forcing me to cross-check against chemical structures or supplier docs. Synonym lists seem tedious, but they’re vital for tracking research, supply chains, and regulatory filings that keep labs safe and compliant.

Safety & Operational Standards

Using this compound means following the rules: gloves, eye protection, and fume hoods as standard precautions. Material Safety Data Sheets warn of risks if swallowed or inhaled, and stories circulate in the lab about accidental spills leading to skin irritation or coughing fits. Facilities keep spill kits and wash stations nearby. Proper handling habits save grief—especially when scaling up reactions or cleaning contaminated glassware. Safe disposal takes priority because aquatic toxicity threatens water systems, and careless drains undercut hard-fought environmental gains.

Application Area

Outside academic walls, the compound sees life in antimicrobial coatings and household cleaning agents. In my experience, teams have test-driven it for dental rinses targeting oral bacteria, with research papers backing its ability to clamp down on Streptococcus mutans and related strains. The textile industry sometimes turns to it for anti-static treatments, and in certain pharmaceuticals, formulators use its detergent properties to solubilize stubborn ingredients. At research benches, it plays a key part in studies on protein folding, membrane biophysics, and analytical sample preparation.

Research & Development

Scientific curiosity never flags. Research groups probe 1-Dodecylpyridinium bromide for new applications: as a DNA extraction reagent, as a possible component for nanomaterials, in controlled drug release technologies, or as a stabilizer in emulsions for diagnostics. The compound’s effects on lipid bilayers piqued keen interest in biological physics, prompting sophisticated spectroscopy and microscopy studies. Funding agencies want projects that promise safer or more effective surfactants; some of the most creative work comes from student teams unburdened by commercial pressures, experimenting with green chemistry routes or greener alternatives to traditional solvents.

Toxicity Research

Questions about safety led toxicologists to dig deep. Studies show that 1-Dodecylpyridinium bromide acts as a strong irritant, harmful to aquatic life and potentially problematic for mucous membranes in humans. Chronic exposure has flagged risks to organ health in animal models, though much depends on concentrations and method of exposure. Lab animal tests delivered decisive warnings about dosage limits and bioaccumulation. The data forces manufacturers and regulators to weigh benefits against potential hazards, sometimes spurring calls for new analogues with gentler environmental footprints.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, there’s a push for surfactants that blend strong antimicrobial activity with low environmental persistence. Synthetic chemistry may deliver better analogues, but 1-Dodecylpyridinium bromide’s established record ensures it won’t slip quietly into obscurity. The move toward “greener” chemicals nudges companies to revise formulas and tweak production pathways, reducing waste and danger. Meanwhile, academic groups keep digging for unexpected uses—citing advances in nanomedicine, synthetic biology, and high-sensitivity diagnostics. The story of this compound, like so many in chemistry, unfolds at a junction of need, creativity, and responsibility.

Understanding Its Place in Real-World Settings

1-Dodecylpyridinium bromide, better known as a quaternary ammonium compound, doesn’t stand out by name to most people. It earns its keep by working quietly in products and processes many encounter regularly. I’ve seen its utility pop up in surprising places, and its role deserves some unpacking.

How It Shows Up in Cleaning and Disinfection

Hospitals, dentists, and other health services don’t have much room for guesswork about cleanliness. This compound comes up again and again in disinfectants, because it can break down tough bacterial cell walls and stop infections in their tracks. I remember visiting clinics during flu season and noticing the effort that goes into surface care. Recent studies point to long-chain quaternary ammonium salts like this one for their broad action against bacteria and some viruses. They don’t just wipe, they help keep the spread of dangerous microbes low.

Professional cleaners without this compound would face a tougher time scrubbing out grime that shelters unwanted bacteria. Consumer surface cleaners on store shelves often contain relatives of this chemical, showing just how far its influence spreads from hospital to home.

Role in Water Treatment and Industrial Processes

Municipal water treatment stations look for results, not glamour. Surfactants such as 1-dodecylpyridinium bromide handle some unique challenges. The compound’s ability to stick to oily residues and disrupt biofilms lets it clean up contaminated water supplies more effectively. Engineers in wastewater treatment often choose chemicals like this one based on safety data and track records for breaking down persistent messes.

Industrial labs running experiments in chemistry or biology also lean on this molecule. It’s a cationic surfactant, which means it interacts well with negatively charged particles in solutions, making it useful in separating mixtures or keeping particles suspended. This isn’t a newsworthy moment most days, but lab results across food, pharmaceutical, and environmental research depend on the steady workhorses like 1-dodecylpyridinium bromide.

Personal Care Products and Formulation Strategy

The bottle of mouthwash you grab at the drugstore may owe part of its punch to this compound. Its action as a bactericidal agent helps manage risk of gum disease and tooth decay. Formulating a rinse isn’t just about taste or color; it’s about ingredients that compete with mouth bacteria, and 1-dodecylpyridinium bromide does some heavy lifting. Reading ingredient labels makes it clear that common oral care brands trust this tool for its reliable results.

Pointing Toward Safety and Sustainability

Every chemical solution draws scrutiny for its impact beyond its main tasks. Studies on quaternary ammonium compounds raise questions about long-term ecological effects, especially with repeated use in large-scale cleaning or water systems. Regulatory agencies, including the EPA and the European Chemicals Agency, constantly update guidelines to balance strong performance and environmental safety. Researchers are working on “greener” surfactants or ways to limit exposure to waterways, which shows that chemical use and responsibility can go hand in hand.

Keeping up with new regulation, redesigning manufacturing lines, or finding biodegradable substitutes isn’t simple. Decisions rely on transparent information, updated independent studies, and open forums among chemists, environmentalists, and policymakers. Products that clean, care, and protect families or patients matter more when their production stays mindful of wider consequences.

Understanding the Basics

Walk through most chemistry labs, and you might find containers labeled with long, tongue-twisting names. Let’s take 1-Dodecylpyridinium Bromide. The name itself may bring back memories from a college chemistry course or the label on household cleaning agents. Yet the real story sits in its chemical formula: C17H30BrN. Each letter and number reveals details about structure, properties, and uses that impact everyday life more than most folks realize.

Why This Formula Stands Out

Chemical formulas don’t just fill dusty textbooks. They lay out, in simple terms, how atoms bond and behave. For C17H30BrN, there are 17 carbon atoms, 30 hydrogen atoms, and one each of bromine and nitrogen. That long chain of carbons (the ‘dodecyl’ part) connects to a pyridinium group—a structure related to pyridine, which carries its own set of unique properties. Bromine tags along as a counter ion. You see this type of arrangement in surfactants, which are the backbones of detergents, disinfectants, and some specialty pharmaceuticals.

Everyday Relevance

Working in the lab, I’ve watched 1-Dodecylpyridinium Bromide break down stubborn grease on glassware. Its molecular makeup gives it amphiphilic character, meaning it has both water-loving and oil-loving parts. That’s the trick: this molecule wraps around grease and holds it so water can rinse it away. But it’s not just about cleaning. Healthcare workers use quaternary ammonium salts in infection control. This particular compound, with its specific formula, disrupts the protective barriers of some microbes, knocking them out cold. Recent studies have shown these compounds can help battle hospital-acquired infections, which spike medical costs and risks each year. That’s a serious, real-world impact tied directly to the atoms lined up in that formula.

The Risk Side of the Formula

Follow the trail from lab bench to environment, and the same structure that gives cleaning power also raises questions. Surfactants sometimes linger in water supplies. The bromine and nitrogen tucked into this formula could break away under some conditions; then, byproducts might threaten aquatic life or disrupt wastewater treatment. I’ve spoken to colleagues who run eco-toxicity tests and worry about the balance between keeping environments safe and keeping infection rates low. The effects of quaternary ammonium compounds on algae and other water creatures are not fully understood, but early warning signs point to caution.

Finding A Smarter Way Forward

Switching to safer chemicals or improving waste treatment seems simple on paper, but industry turns slowly. Better disposal protocols in hospitals, or tweaks in molecular design to break down faster after use, could tip the scales. Researchers experiment with shorter alkyl chains or biodegradable counter ions. The difference boils down to chemistry: shuffle the atoms in the formula, and the whole landscape of risks and benefits can shift. It’s a reminder that knowing and understanding chemical formulas is more than rote memorization—it plays a role in public health, environmental policy, and day-to-day life.

Reality in the Lab: Safety with 1-Dodecylpyridinium Bromide

1-Dodecylpyridinium bromide falls under a group of chemicals known as quaternary ammonium compounds. On paper, it sounds like something cooked up in a distant branch of chemistry, but it finds its place in the world as a surfactant and as a disinfectant in laboratories. Anyone who spends time in a lab probably encounters surfactants like this one when cleaning glassware or prepping bioscience experiments. Even though bottles come with warnings, repeated use tends to make people overlook real concerns about exposure.

Direct Exposure Risks: What Actually Happens?

Chemicals carry stories of harm and healing. With 1-dodecylpyridinium bromide, skin and eye irritation take center stage. If splashed or spilled, redness, itching, or even burning sensations can develop. On the respiratory side, breathing in dust or aerosol can trigger coughing and throat irritation. Over months, some who handle powders without gloves or masks might notice chapped hands or minor eye problems that never seem to fully go away. Research published in the Journal of the American College of Toxicology documents moderate skin irritation from quaternary ammonium compounds, pointing toward a real need for respect in the lab.

Environmental groups point fingers at these compounds for their persistence in water systems, citing studies from Environmental Science & Technology. Wastewater treatment plants can remove a lot, but traces still slip through. Local streams, where aquatic life thrive, end up bearing the brunt.

Why Experience and Common Sense Matter

Writers and accident reports repeat these lessons every year—don't eat near your bench, wear splash goggles, and grab gloves before reaching for any chemical, not only the ones marked "danger." Years back, a careless reach put me in urgent care with chemical burns, even with "routine" reagents. Regulations like OSHA set guidelines, but personal experience teaches the hardest lessons. Without respect, repeated and cumulative exposure piles up, and minor problems become real health risks.

Supporting Claims with the Evidence

Data from the U.S. National Library of Medicine show acute oral toxicity in rodents at moderate doses, meaning ingestion is risky. Even low-concentration solutions, prepared for disinfecting medical instruments, can irritate skin. Some healthcare settings opt for less aggressive compounds, but substitutions vary by cost and regulation.

Rules aren't only for those afraid of chemicals; they're built on long, sometimes painful lessons. In 2021, OSHA reported more than 500 chemical exposure cases in clinical labs across the country, many linked to improper storage and lack of proper ventilation. These numbers could drop with even basic compliance and vigilance.

Pushing for Better Habits and Solutions

As awareness grows, universities and employers update safety training. Modern Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) explain side effects in plain language. Ventilated fume hoods, regular glove changes, and proper disposal of contaminated materials form the backbone of safer labs.

Chemical manufacturers have begun reformulating products, offering variants with milder profiles. Calls for biodegradable surfactants push labs to consider not just worker health, but the environment downstream as well. Conversations between users, managers, and makers drive safer work environments, making chemical safety a living topic, not just something in a binder.

Bottom Line

Ditch shortcuts. Personal stories and robust research arrive at the same advice: put safety first. Use gloves, respect the warnings, and keep your space clean. Each bottle of 1-dodecylpyridinium bromide deserves full awareness, not routine handling.

Understanding What’s at Stake

I’ve spent years working around chemicals in labs and small production spaces, and I know from experience: storage isn’t just an annoying detail—it’s often where most safety mistakes start. For something like 1-Dodecylpyridinium Bromide, a quaternary ammonium compound, that lesson’s especially relevant. This chemical tends to show up in disinfectant settings, specialty cleaning, even, sometimes, experimental work in universities. If your team stores it like table sugar, problems can sneak up fast.

Spotting the Issues

First off, this isn’t an everyday household item. Direct contact isn’t harmless. Irritation happens quickly, especially with skin and eyes. Inhaling dust isn’t clever, either, and the powder can drift. Years back, I watched a promising lab tech open a bag too quickly. He spent the afternoon rinsing his face and going over the material safety sheet. Lesson memorized.

The Real-World Storage Solution

Storage rules make more sense when you’ve watched mistakes happen. Here’s how I treat something like 1-Dodecylpyridinium Bromide:

- Keep containers tightly sealed: I always put this at the top of my list. Every time I’ve seen contamination or caking, it started with a lid left loose. Chemicals draw moisture from the air. Lids go back on as soon as possible, with a clean seal.

- Choose a dry, ventilated area: Damp, enclosed spaces turn powders like this clumpy or sticky. I stick with shelving that doesn’t sit near sinks or wash stations. Temperature swings should be minimal—a constant, cool temperature keeps shelf life predictable and the product easier to handle.

- Avoid sunlight and heat: Bright rooms speed up chemical breakdown, and in rare cases, heat creates pressure inside containers. I’ve seen labels peel off in direct sun, making identification tricky. I keep containers on lower shelves, away from light sources and direct heat.

- Label every batch: Even good memory fails eventually. I scan and print updated labels with hazard information—no shortcuts, no scribbled sharpie marks. If a container holds an older batch, I make a note to use it first, especially if there’s an expiration.

- Segregate from incompatible materials: I’ve learned not to store quaternary ammonium compounds near acids or oxidizers. Accidents happen when incompatible chemicals share a shelf. Physical distance, even a simple plastic bin, can mean the difference between an ordinary day and a mess.

Preparing for Accidents

No matter how well you organize things, human error still happens. For that reason, I keep goggles and gloves close to where I access the stored chemicals, not buried in a drawer across the room. If there’s ever a spill, I have designated absorbents ready. MSDS sheets should be up to date and easy to find. In the past, I saw teams try to “wing it” without proper backup—every time, someone got hurt or product got wasted.

Being Ready for the Long Haul

Long-term storage doesn’t just involve tossing a jar in a cabinet and forgetting it. I set a calendar reminder to inspect stored chemicals every few months. Look for leaks, bulges, or clumping. It just takes five minutes, and it’s saved me hours of clean-up and paperwork more than once.

Why All This Matters

Maybe storing chemicals looks boring compared to the more exciting parts of lab work. In my experience, this is where experience shows. Following sound storage steps isn’t just a formality or a regulatory box to check—it’s respect for your coworkers, your workplace, and your own safety. Small habits, repeated every day, make for fewer disasters and much smoother work in the long run.

Understanding What 1-Dodecylpyridinium Bromide Does in Water and Beyond

1-Dodecylpyridinium bromide finds use in a lot of practical places—mostly because it mixes with water in a way that makes it useful for cleaning and separating things. If you work in a research lab, or you’re involved with making personal care products, you learn pretty quickly that this compound, with its long 12-carbon tail and its pyridine ring, behaves differently than simple salts like table salt or sugar.

Unlike regular salts, 1-dodecylpyridinium bromide comes with a big, greasy part (the dodecyl chain), which doesn’t like water much, and a charged head (the pyridinium and bromide) that loves water. Toss a bit in water and you get this fascinating result: the chemical lines up at interfaces and makes little spheres called micelles. These structures help grab grease and oils that water alone can’t handle. That property sits behind why it’s used in surfactants, antimicrobial agents, and sometimes even for DNA extraction in biotech.

Why Solubility Questions Matter

If you’ve ever tried to dissolve 1-dodecylpyridinium bromide, you’ve probably noticed it goes into water much more easily than it does in most organic solvents. Chemically, water pulls in the charged part and screens it from the greasy tail, making those micelles possible. In ethanol or methanol, you’ll get some solubility, but nowhere near as much—you’ll see cloudy mixtures or even undissolved lumps unless you use a lot of solvent or heat things up. Drop it in true nonpolar solvents like hexane or toluene and you’re out of luck; nothing happens. That kind of selective solubility makes it special if you need something to work at the border of oil and water, literally or figuratively.

From work at the bench, I’ve seen students struggle when they don’t realize how temperature shifts or adding a bit of alcohol changes the game. Heat can boost solubility, but you risk breaking down delicate ingredients or running into deposit problems as mixtures cool. Small tweaks matter—a little salt or a pH shift can send micelles out of solution or change their size, a trick often used in biotech and water treatment to pull things out at the right moment.

Solving Real-World Problems with the Right Information

Solubility guides how this compound gets used beyond the lab. In cleaning, producers pick it for its ability to hold oil droplets away from surfaces, letting detergents work at lower concentrations. In health care and personal hygiene, it shows promise because it stays active in water—helping to manage bacterial contamination or act as a preservative. Yet, poor understanding about mixing and concentration leads to waste, clogged filters, or inefficient processes.

I’ve seen manufacturers save money—and reduce chemical waste—by matching the solvent to the job. In my experience, half the headaches come from ignoring this property and pushing too much of the chemical, chasing dissolving power with heat, or using unnecessary boosters. Scaling up production safely means checking that mixing is thorough and that nothing drops out, especially as batches cool down or hit new ingredients.

Looking at published data, pure water handles roughly 0.57 to 0.7 grams of this chemical per 100 mL at room temperature. That’s a solid foundation for calculating batch sizes or setting up experiments, but it all shifts with temperature, pH, and the presence of other electrolytes. Because this salt can change from fully dissolved to forming solid deposits with a small shift, it’s important to watch your process closely.

Better Outcomes Through Practical Knowledge

In research and manufacturing, it pays to understand the gritty details of solubility. Making choices based on hands-on experience and published solubility numbers leads to fewer surprises, more reliable results, and less downtime. Whether mixing up solutions in a school lab or developing a detergent for the global market, keeping an eye on the way 1-dodecylpyridinium bromide reacts to its environment lets you work smarter. That’s real expertise, based on solid facts mixed with a little practical trial and error.