1-Ethyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Acetate: An In-Depth Look

Historical Development

Chemists started focusing on ionic liquids like 1-Ethyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Acetate in the late 20th century, searching for solvents that could sidestep the environmental downsides of more traditional options. Early adopters in academic labs saw potential in these salts, which stay liquid at room temperature. The imidazolium family, in particular, grabbed attention for their low vapor pressure and outstanding stability. As patents rolled out and industry discussions followed, researchers kept pushing to find liquids that could carry out tough chemical jobs with less environmental baggage. Over the past two decades, 1-Ethyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Acetate slowly gained its own following thanks to a strong track record in dissolving cellulose, among other things. I remember the first time our group used it in a small biopolymer project; the efficiency was eye-opening and led us to rethink how we approached certain separation processes.

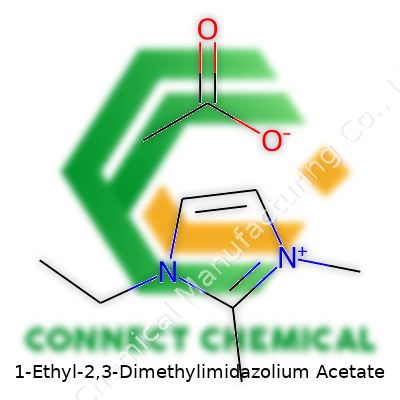

Product Overview

1-Ethyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Acetate falls into the category of organic ionic liquids, featuring a positively charged imidazolium ring substituted with ethyl and methyl groups, paired with an acetate anion. This structure shapes its behavior as a powerful, non-volatile solvent. Suppliers offer it as a clear or lightly tinted liquid, packaged in sealed bottles since it draws moisture from the air. Most use it for advanced chemical synthesis, polymer processing, difficult separations, and small-scale pharmaceutical development. Having handled it in my own bench work, I can tell you the ease with which it breaks down certain biomass fibers quickly sets it apart from standard lab choices.

Physical and Chemical Properties

This liquid usually appears colorless to light yellow, with a density running around 1.05 to 1.10 g/cm³ at room temperature. It barely evaporates, which makes it stand out when compared to volatile organic solvents. Its melting point falls below 0°C, while its boiling point sits out of reach under atmospheric pressure, since it breaks down before boiling. High polarity and strong hydrogen-bonding character give it remarkable power to dissolve cellulose, lignin, and a slew of other biopolymers. Water gets absorbed easily, and its viscosity can climb with greater water content. Such robust solubility comes at a cost—using it for basic extractive work can take some skill. Electrochemical experiments also benefit, since its ionic nature yields wide electrochemical windows and low flammability.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Batches of 1-Ethyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Acetate come labeled with key identifiers such as the CAS number, purity percentage (often over 98%), and moisture content. Reputable suppliers provide certificates showing absence of halides, heavy metals, and other impurities. Storage tips point toward using airtight containers in cool, dark places to keep both the liquid and label intact. Some regulatory agencies ask for clear hazard information: warnings to avoid skin and eye contact feature prominently. As a chemist, reading these labels thoroughly before even opening the bottle always struck me as common sense. Proper record-keeping for each container helps support traceability in R&D settings.

Preparation Method

To prepare this ionic liquid, laboratories typically react 1-ethyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium halide with silver acetate or potassium acetate under dry, inert atmospheric conditions. The halide first forms through an alkylation/hydrolysis sequence involving the corresponding imidazole ring precursor. Following the anion-exchange reaction, the byproduct (like silver halide) drops out of solution and gets filtered off. The product then goes through repeated washes and careful drying to remove all water and remaining salts, using techniques learned in basic preparative organic chemistry. The precision with which this liquid must be dried reminds me of early days learning the patience needed to hit the target purity.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

This ionic liquid acts as both a solvent and a reactant scaffold. It dissolves cellulose, lignin, and chitin—biomaterials that usually resist all but the harshest acids or bases. Researchers have shown strong results using it to catalyze esterification, transesterification, and even some C–H activation processes, all thanks to its powerful hydrogen bonding with substrates. Its cation structure can undergo N-alkylation to adjust physical properties or tweak reactivity for special needs, and the acetate anion sometimes swaps out for alternatives to support greener synthetic pathways. We once explored how the modified version handled a new set of drug precursors, and the results underscored how small structural changes in the liquid influenced every stage of downstream chemistry.

Synonyms & Product Names

Suppliers and researchers often call it by several names: [EMIM][OAc], 1-ethyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium ethanoate, or even the shorthand EMIM Acetate. Trade literature occasionally refers to the substance as part of a family named for similar imidazolium-based liquids. Keeping these synonyms in mind prevents headaches during literature searches or when checking regulations, since typos or small name changes can lead to missed safety alerts. As I sift through supplier catalogs, I now double-check every alternate form to be sure the matching chemical ends up on my purchase sheet.

Safety & Operational Standards

Pure 1-Ethyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Acetate isn’t outright dangerous compared to acids or flammable solvents, but safe handling always matters. Direct skin and eye exposure cause irritation, especially over extended contact. Inhalation of fine aerosols or vapors during heating can stress the respiratory tract. Researchers typically work with latex or nitrile gloves, splash-resistant glasses, and, in some cases, fume hoods. Practical habits—like glove changes after spills and thorough site cleanup—form an everyday routine. Waste from reactions containing this liquid heads into specialized organic solvent containers for professional disposal. Training newcomers on proper first-aid measures felt crucial when we onboarded students, as confidence with spill response builds safe work spaces.

Application Area

Scientists working in advanced material processing lean heavily on this acetate salt for dissolving and restructuring plant materials, particularly in renewable energy research and biopolymer engineering. Major chemical suppliers now pitch it to labs looking for alternatives to toxic metal catalysts or petroleum-based solvents. Pharmaceutical synthesis sometimes benefits from its role in highly selective reactions, while battery and electrochemical developers leverage its low flammability and tolerance to both high and low voltages. On a personal note, the liquid’s performance on dissolving stubborn batches of cellulose pulp stood out during collaborative projects with chemical engineers focused on biofuel innovation, leading directly to higher yields.

Research & Development

Labs across Europe, North America, and East Asia constantly seek improvements on both the chemistry and engineering around ionic liquids. Since the late 2000s, the patent space has filled up with ideas to recycle and reclaim the acetate liquid from reaction waste or to tune its structure for less environmental persistence. Many development teams now chase applications in green chemistry, hoping to replace industry stalwarts like NMP or DMF. Still, the high cost per kilogram and labor-intensive recovery techniques present clear bottlenecks, especially for larger production lines. My time in a government-funded pilot plant made it clear that achieving broader adoption means cutting both environmental and financial costs at every step.

Toxicity Research

Long-term toxicity studies for 1-Ethyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Acetate point to moderate risk in aquatic environments. It breaks down slowly out in the wild, and some breakdown products can stress freshwater organisms at higher concentrations. Rodent bioassays have shown skin sensitivity but little evidence of acute toxicity at typical exposure levels for adults. Still, routine checks for bioaccumulation risk continue, and regulatory reviews stress close attention to industrial discharge or improper disposal. In academic safety briefings, I always put environmental fate on equal footing with immediate human toxicity, since overlooked chemical waste can haunt industrial sites for decades.

Future Prospects

The future for 1-Ethyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Acetate hangs on the promise of sustainable chemistry and affordable advanced materials. Automation and recycling advances could soon drive down production costs, making it an everyday tool for large-scale biomass processing. Broad policy support for cleaner chemistry may add momentum for industrial investment, driven by success stories in pilot programs worldwide. Green chemists are already experimenting with bio-based feedstocks to avoid petroleum-derived precursors, which could open the door to green-labeled ionic liquids and wider consumer trust. From my conversations at recent green technology conferences, enthusiasm runs high, but the promise still depends on creative engineering and stronger safety data. Finding the balance between function, cost, and sustainability will shape the next chapter, and involvement in multi-disciplinary teams will likely push breakthroughs into industrial reality.

A Closer Look at a Powerful Ionic Liquid

Some chemicals play background roles most people never notice, and 1-ethyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium acetate belongs to that club. This ionic liquid, often called an IL in scientific circles, hardly ever makes big headlines. Yet labs and factories lean on it for several reasons, mainly in fields tied to sustainability and innovation.

Opening Doors in Biomass Processing

This stuff often comes up in discussions about breaking down tough plant materials. Lignocellulosic biomass—the hard-to-crack structure found in woody plants, crop residues, and even paper waste—offers promise for making greener fuels or new materials. Most solvents bounce right off these stubborn fibers. Imidazolium salts like 1-ethyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium acetate cut through that resistance. Researchers found that this liquid can dissolve cellulose, one of the core components of plants, which makes it possible to pull out sugars and turn them into fuels or building blocks for plastics. That matters because the world keeps asking for cleaner, renewable resources.

Cleaner Chemistry with Better Solvents

My time in an academic chemistry lab taught me that most traditional solvents come with headaches—flammability, toxicity, and heavy rules about disposal. This acetate-based ionic liquid barely evaporates at room temperature, stays stable even at higher heat, and often replaces more harmful options. These properties cut down on emissions and dangerous waste. The U.S. Department of Energy and several research hubs worldwide keep encouraging green chemistry like this because industries want to drive pollution lower without ditching performance.

Engine for Advanced Material Production

Making new polymers isn’t just about gathering up different molecules and hoping for the best. Controlled environments matter, especially with batteries, membranes, and specialty plastics. 1-ethyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium acetate gets into the mix as a solvent or a catalyst to help assemble complicated materials with consistent properties. For example, labs use it to help produce cellulose nanofibers, which end up in lightweight composites or flexible electronics.

Challenges and New Directions

Experience shows that nothing in chemical research happens without a challenge. The main hurdles come from cost and the need to recover and reuse this ionic liquid at large scales. A bottle of imidazolium-based IL doesn’t come cheap, and big manufacturers need tons of the stuff. Engineers respond by refining recycling techniques and even developing new recovery systems so that after one processing round, the liquid can come back and work again.

Safety and environmental health count just as much as performance. Some ionic liquids break down into byproducts that demand close scrutiny—no industrial solution lasts if it ends up causing different problems down the line. Teams are still testing long-term toxicity and the effect on water or soil in the case of accidental leaks. Rigorous safety checks, strong workplace rules, and plenty of research all play a role in keeping this tool in the green chemistry toolbox.

Where to Go from Here

Seeing this chemical in action gives people a sense of hope for future manufacturing. From biorefineries to next-generation batteries, researchers and companies turn to it for better control and lower hazards. Looking ahead, the real key comes from blending good science, industrial know-how, and honest conversations about cost and safety. As tools like 1-ethyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium acetate become more common, expect more headlines about cleaner, smarter ways to make what people need.

The Nature of the Compound

1-Ethyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium acetate belongs to the family of ionic liquids. These liquids contain both a positively charged ion and a negatively charged ion. The main thing most folks notice right away is how it holds a liquid state even at room temperature, much like water or oil, but it shows almost no smell and doesn’t evaporate quickly. Skipping the strong odors found in ammonia or even some solvents makes it more pleasant and safer for laboratory work.

In the lab, you pour it out and find it thick, almost syrupy, especially if the temperature drops. This viscosity can make mixing a chore unless you stir consistently or heat it slightly. The clear, usually colorless or slightly yellowish appearance assures you it hasn’t started breaking down from exposure to air or light.

Solubility and Handling

There’s a reason this compound earns attention in green chemistry and material science. It mixes well with water, alcohol, and other polar solvents, creating new pathways for reactions or extractions where other ionic liquids stall. Researchers who work with natural polymers like cellulose see real promise, since this acetate-based liquid dissolves cellulose better than many competitors. That feature stands out in biofuels development or recycling wood waste.

Handling it, you learn quickly not to worry about flammability. Traditional solvents like acetone or ethanol carry fears of fumes and flashpoints; 1-ethyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium acetate doesn’t ignite easily. That doesn’t mean you stop paying attention to gloves and goggles—touching ionic liquids still causes mild irritation for some people, and cleanup wants care because it feels oily.

Chemical Reactivity and Stability

Chemically, the stability in air and resistance to high temperatures set this compound apart. In some settings, it holds together even when heated over 100°C. That resilience under heat pulls it into places like advanced batteries or catalysts, where engineers search for liquids that won’t decompose in harsh environments. If you forget to seal a bottle overnight, this acetate doesn’t break down or lose strength, especially compared to many organic solvents.

In a beaker, it stays put and doesn’t evaporate like water or acetone, which helps with reactions that need consistent ratios over long hours. It resists common degradation paths: light doesn’t cause rapid decay, and oxygen doesn’t tear it apart. Out in the world of application—even in pilot biofuel plants—users don’t see clouds of vapor or the risk of inhaling fumes.

Environmental Impact and Safety

Because ionic liquids came about as an attempt to reduce chemical waste and hazards, safety and environmental impact matter. 1-ethyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium acetate breaks up slowly in the ecosystem. Unlike some classic solvents, it doesn’t rush off into the groundwater or float off as pollution but can linger if spilled. That puts a spotlight on developing proper disposal methods. Chemists are pressing for recycling and re-using these liquids to limit long-term buildup.

In a chemist’s hands, this acetate makes a real difference for safer labs and greener processing. It opens doors to dissolving materials other chemicals can’t, dodges the explosion and fire threats that haunt older solvents, and makes big leaps toward cleaner chemical practices—provided everyone pays attention to what happens at the end of its working life.

Understanding the Chemical

1-Ethyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium acetate sounds like a mouthful, but at its core, it’s one of those ionic liquids turning up in new labs every year. Some researchers use it for dissolving cellulose, some for catalysis. For those who spend enough time around chemicals, it’s another bottle with a complicated name, but it deserves a clear-eyed look in the safety department.

Risks in Real Terms

This compound hasn’t been around for as long as old staples like acetone or ethanol, so hazard data is a bit thinner. Even so, its imidazolium base and acetate pairing give enough clues. Experience shows ionic liquids can be less volatile than solvents most people know from high school. They often stay put on a bench, not filling the air with fumes. Anyone who has cleaned up after a sticky ionic liquid spill knows the lack of vapor masks deeper issues; slow evaporation does not mean harmless.

Imidazolium-based chemicals come with a reputation. Many researchers who spend years with these liquids or similar alkyl compounds see patterns—skin irritation, accidental splashes causing red spots or tingling, headaches in poorly ventilated spaces. Animal studies and safety reports support the picture. The acetate bit brings extra risk—acetic acid can irritate eyes, skin, and upper airways.

Protective Steps that Work in Practice

Nobody wants to lecture about safety goggles, but sharp pain in the eyes is a hard way to learn. Every lab accident I’ve seen started with small shortcuts: skipping gloves, wearing T-shirts, saving time by working on an open bench. Chemical burns and rashes make people pay attention soon after. Nitrile gloves keep skin out of the chemical. Long sleeves, closed-toed shoes, and goggles do what they’re supposed to, whether it’s day one or year twenty in the lab.

Fume hoods get new appreciation when handling liquids with unknown or poorly understood volatility. Even if the odor is faint, toxicologists remind us skin and lungs are front-line absorbers. Good ventilation, proper use of hoods, and not trusting a nose to judge safety save people from slow-building toxic effects.

Spills, Storage, and Waste

Sticky, slow-pooling spills set up real problems because they keep touching skin or surfaces unless they’re cleaned fast. Absorbent pads and nonflammable, alkaline neutralizers do the job better than paper towels. Every bottle should have a label and stay out of sunlight. Ionic liquids may not burn like gasoline, but improper storage makes breakdown more likely, releasing unknown byproducts.

Disposing of leftovers down the sink is wishful thinking. Hazardous waste bins and collection sites keep these chemicals out of the water system, where old pipes or sensitive freshwater ecosystems have little protection.

Learning from Others

The more scientists work with novel chemicals, the more stories come out about unexpected rashes or mystery headaches after cleanup. Sharing stories and reading up on journals fills in data gaps that safety sheets can’t always cover. Even old hands take a second look after a close call. Following universities' protocols, double-checking labels, and not trusting gut feel keep people safer in the long run.

At the end, handling 1-ethyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium acetate calls for basics: protect skin, eyes, and lungs; label and store bottles right; clean up with the right materials; and toss wastes into proper containers. Trusting experience, both personal and shared, makes the difference between a routine day and a trip to the nurse’s office.

Real Steps for Storing Chemical Ionic Liquids

1-Ethyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Acetate probably won’t appear in a casual setting. This chemical belongs to the ionic liquids, a newer class of compounds you usually spot in research labs or certain advanced manufacturing. Ionic liquids have a reputation for being more versatile and less volatile than older organic solvents, but proper storage can stop your project from turning into a safety issue.

Why Air and Water Matter

Many ionic liquids, including 1-Ethyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Acetate, draw water from the air. Keep a bottle of this stuff open for too long, and soon it ends up diluted. Water soaking in may sound harmless, but pure research results depend on chemical purity. Any chemical change makes it harder to trust the data. I’ve seen a year’s worth of careful prepping undermined by a careless storage habit.

To stop this, close the cap and seal containers after each use. Some labs invest in glove boxes filled with dry nitrogen or argon, but at home or in smaller setups, a simple dry desiccator cabinet does the job. Toss in fresh desiccant and check often. This habit keeps the chemical away from not only water, but also carbon dioxide, which can trigger its own small chemical shifts.

Temperature Makes a Difference

Ionic liquids break from the old solvent rulebook by not flashing off at room temperature. But 1-Ethyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Acetate can still degrade if it spends time above 30°C. Most storage rooms grow stuffy once summer hits or equipment runs hot. Regular air conditioning won’t always guarantee a stable environment.

Keep containers in a cool cabinet, away from direct sunlight or heat vents. Lab refrigerators not used for food storage offer the extra step to keep temperature consistent. If it’s out on the bench top, sunlight turns it yellow or brown, harming both looks and functionality. I always log the storage date and run a purity check each season as insurance.

Reporting Changes Keeps Everyone Safe

In most labs, you’ll find a notebook or spreadsheet tracking stock chemicals. It’s not bureaucracy—it’s the frontline of lab safety. 1-Ethyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Acetate spills leave sticky, hard-to-clean residue. Safety goggles and gloves feel cumbersome, but skin contact causes irritation within seconds.

No matter how many years you’ve worked with solvents, staying bluntly aware of the risks keeps coworkers and yourself safer. A single chemical exposure can knock a lab tech out of work for weeks. Cleaning up after a careless spill takes a fraction of the time compared to filing a health incident report.

Disposing Responsibly, Not Down the Sink

Even though this chemical doesn’t evaporate much, improper disposal harms wastewater systems. In my experience, containerizing all ionic liquid waste and using official hazardous chemical disposal channels helps local ecosystems stay chemical-free. Small amounts add up across an industry, and skipping the right processes leads to bigger headaches for waste managers.

Anyone storing chemicals this advanced won’t get far without learning accountability. Respect for these basics, checked regularly, sets good research apart from wasted effort and damaged equipment.

Getting Real About Purity

Working with chemicals, I’ve learned purity isn’t some minor checkbox on a spec sheet. For 1-ethyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium acetate, high purity levels matter if you want dependable results. Most labs look for at least 98% purity, but top suppliers reach over 99%. Lower purities can drag down reaction yields, affect material stability, and skew data. In my experience, any shadow of moisture or metal contamination leads not just to wasted time, but cascades into failed syntheses or faulty application results.

Independent testing makes a big difference. Suppliers that regularly publish third-party HPLC, NMR, or elemental analysis appear much more trustworthy, especially with specialty chemicals like this ionic liquid. Cutting corners with lower-purity product to save a few dollars costs more long term, especially in pharmaceutical or energy tech projects where every impurity amplifies risk.

Looking at What’s on Offer

Packaging sizes for 1-ethyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium acetate don’t just reflect convenience; they tell a story about how the industry views safety, handling, and cost. Researchers typically find this compound available in small bottles—10 grams, 25 grams, and occasionally 100 grams for routine R&D. Larger containers, including 500 grams up to 1 kilogram, mainly show up in custom orders or for established production lines.

I’ve faced situations where buying a small amount cost more per gram, but the alternative meant storing half a kilo of a sensitive liquid with a shelf-life that security guidelines barely tolerate. Smaller bottles offer clear handling benefits, especially in academic or pilot environments with limited safety setups. With sensitive ionic liquids, oxygen and water fraction in storage air degrade quality, so manufacturers often recommend nitrogen-sealed or vacuum-tight vials.

Why Purity and Size Decisions Stick With You

Early on, I thought high-purity only mattered for big-budget or regulatory-driven applications. Pretty soon, you see the economics flip—a cheap, lower-grade chemical brings headaches: inconsistent results, more purification steps, even extra disposal headaches. For 1-ethyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium acetate, high purity—usually above 98%—saves more money in repeatable output than it ever costs up front.

The specific packaging size depends on your plans. Tiny 10- and 25-gram vials work well if you’re just running a handful of reactions. Process engineers planning to scale up might go for kilogram batches, but that means strong training in chemical storage and disposal. The wrong container size means leftovers; leftovers often turn into compliance nightmares if not handled by someone who cares. If you’re careful about how much you order, you keep costs tight and quality higher.

Smart Practices and Solid Solutions

Suppliers with quick access to purity certificates, clear packaging specs, and responsive tech support build trust fast. In my own work, I lean on trusted suppliers who show batch-specific documentation. Good handling habits matter—always opening containers in inert-atmosphere boxes, logging batch numbers, and tracking expiration dates.

For teams using 1-ethyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium acetate, staff training matters as much as paperwork. A reliable safety network, clear labeling, and tight storage procedures keep operations smooth. Leaning on suppliers committed to tight purity controls, and buying just enough for a single round of experiments, goes a long way in managing costs, quality, and peace of mind.

Making informed choices about purity and packaging doesn’t just reduce risk. It keeps projects on track, budgets under control, and everyone a bit safer in the lab.