1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Thiocyanate: A Deep Dive into an Innovative Ionic Liquid

Historical Development

People started looking toward ionic liquids for their unique solvent properties well before the turn of the century, and plenty of researchers stumbled across 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate (EMIM-SCN) as a standout among these. Laboratories in Europe and Asia played with imidazolium salts, noticing right off their low volatility and stability under both heat and air. Over time, universities published article after article on new ways to synthesize and customize such salts, with EMIM-SCN moving from laboratory curiosity to a tool for green chemistry. This interest only grew as sustainability started to matter more to industrial chemistry and folks in academia alike, pushing ionic liquids from fringe material to mainstream solution for dissolving, separating, and even storing energy.

Product Overview

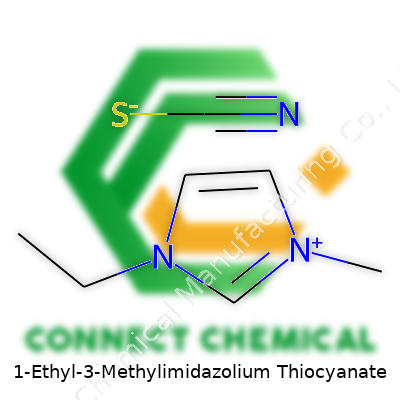

EMIM-SCN comes from the family of ionic liquids built out of the imidazolium ring system. This compound forms by combining 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium cations with thiocyanate anions. The result is a substance that has liquidity at room temperature, unusual chemical stability, and the ability to dissolve a diverse list of molecules. Chemists don’t use EMIM-SCN in massive scale consumer applications; it’s better known to those who mix solvents in a lab or want a safer alternative to more volatile, hazardous organic solvents. Over the years, industries dealing with difficult-to-handle chemicals or rare earth elements have relied on compounds like EMIM-SCN for niche but critical tasks.

Physical & Chemical Properties

EMIM-SCN appears as a colorless to light yellow liquid. It resists vaporization and holds its form in open air. The odor is faint, making it less intrusive in closed environments. Its melting point sits below room temperature, so it remains half fluid, half solid in a cold storage lab but fully liquid under standard storage. Density ranges between 1.05 and 1.2 g/cm³, while viscosity depends on temperature but registers higher than water even in a warm room. Conductivity registers enough to conduct ions without supporting a metallic current, and this ionic liquid performs steadily across a wide pH and temperature window. Solubility leans toward polar compounds; it loves salt, certain metals, and even some gases, though big oil molecules tend to float on top.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Manufacturers label EMIM-SCN with technical data including purity (often >99%), water content (typically kept below 1% for sensitive operations), and trace ion impurities. Batch filings usually include moisture, pH, and heavy metal tests because small contaminants sometimes throw off research or industrial use. Labeling regulations require hazard pictograms in line with global harmonized standards. I’ve noticed more effort by suppliers lately to give unambiguous traceability, including batch origin and manufacturer’s contact details, since even tiny changes in purity throw off crystallization or metal extraction performance.

Preparation Method

The most direct route to EMIM-SCN starts by stirring up a solution of 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide in water or acetonitrile. Next, you add potassium thiocyanate carefully; after some hours under heat, a double displacement reaction pushes potassium bromide out as a white solid, while EMIM-SCN stays in solution. You filter the salts, evaporate the solvent under vacuum, and—after some purification and maybe a drying step—you’re left with clear or straw-colored EMIM-SCN. Chemists rely heavily on glovebox techniques for any scaling-up, since even atmospheric moisture changes how pure, and therefore how functional, the product is. Sometimes, column chromatography gets involved if a researcher wants to get rid of colored byproducts.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The imidazolium cation in EMIM-SCN resists breakdown in acids, bases, and even mild oxidizers. The thiocyanate group, on the other hand, reacts with transition metals to form fascinating complexes, which makes it popular in extraction work. I’ve seen protocols that add hydrogen peroxide to EMIM-SCN; this oxidizes the thiocyanate and forms a host of sulfur-nitrogen compounds, letting chemists tailor the ionic liquid for specific separations or catalysis. In laboratories, functional groups are sometimes attached to the imidazolium ring to tweak solubility or chelating power. For specialized synthesis, researchers swap the alkyl substituents on the imidazolium, but the ethyl-methyl combo offers the best balance between liquidity, chemical stability, and cost.

Synonyms & Product Names

Aside from “1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate,” the world knows this compound under a few different monikers: EMIM-SCN, [EMIM][SCN], and its registry numbers in chemical catalogs. Some suppliers list it as “ethylmethylimidazolium thiocyanate” or “imidazolium thiocyanate ionic liquid.” Walk into any scientific warehouse or scroll an online retailer’s catalog, and you'll stumble on similar products under these variations. Keeping track of synonyms becomes crucial for ordering the right material; the last thing any lab wants is to pay a premium for a cation or anion swap.

Safety & Operational Standards

While EMIM-SCN has a reputation for being less hazardous than many volatile organic solvents, it doesn’t mean it’s free from risk. The substance irritates eyes and skin if handled without gloves or goggles, and spills on lab benchtops sometimes seep into porous materials. It almost never catches fire, but heating it above 200°C releases fumes that sting the nose. I stick with disposable gloves and fume hoods, following SDS recommendations. It’s good practice to keep large containers sealed, away from strong acids, and to clean up with absorbent materials rather than just a paper towel. Disposal rules call for collection as an organic waste, not down the drain. Environmental persistence studies suggest EMIM-SCN does not biodegrade easily, so treating any waste as hazardous makes sense.

Application Area

Industries and research groups driving toward greener chemistry have embraced EMIM-SCN thanks to its ability to dissolve metal salts, facilitate electrochemical reactions, and act as a medium for crystallization. Folks working on battery electrolytes screen this ionic liquid to replace more toxic or volatile components. Analytical labs favor it for extracting rare earth or transition metals out of ores using liquid–liquid extraction instead of high-energy roasting. The selective nature of thiocyanate means gold, silver, copper, and platinum bond with the anion and leave other metals behind. I’ve seen colleagues in pharmaceutical development use EMIM-SCN as an alternative solvent to make purification and crystallization friendlier and more consistent. Even biotechnologists experiment with it for enzyme stabilization and protein solubilization, though applications remain early stage.

Research & Development

Recent research efforts drive EMIM-SCN’s properties into service for electrochemistry and sustainable separations. One branch tests it inside next-generation supercapacitors and batteries, counting on the ionic liquid’s wide electrochemical window and low vapor pressure to push operating voltages higher. Other groups work out new solvent systems for recycling precious metals from electronic waste, with EMIM-SCN caught in the middle because of its selectivity and recyclability. The theoretical work on EMIM-SCN keeps pace, too—the journals are buzzing with computational chemistry studies mapping out its interaction with various organic and inorganic targets. Not every study shows breakthrough results, but the slow, steady accumulation of data moves this field forward. Innovation in manufacturing methods—the search for scalable, less wasteful syntheses—also gets attention in chemical engineering departments aiming to roll out new ionic liquids at lower cost with reduced environmental burden.

Toxicity Research

Toxicologists look closely at EMIM-SCN’s safety profile. Many studies confirm it poses lower inhalation and flammability risk than conventional solvents. Yet, its impact on aquatic organisms and microbial ecosystems remains a concern, since the thiocyanate group has potential to disrupt cellular processes in low concentrations. Rodent trials point out modest toxicity by oral and dermal routes, prompting experts to label EMIM-SCN as an irritant rather than an acute toxin. I recall several studies in journals advocating for more ecotoxicology screening before wide-scale industrial adoption. More recently, regulators call for full lifecycle studies on ionic liquids, including EMIM-SCN, to pin down their effect during disposal or accidental spills. Users with lab or factory exposure must wear gloves, goggles, and sometimes masks not because of high toxicity, but simply out of an abundance of caution while potential environmental links remain under investigation.

Future Prospects

People expect a lot from EMIM-SCN and compounds like it as industries move away from traditional solvents. Global attention on sustainable and efficient chemical processes lines up with the USP of this ionic liquid: low emission, nonflammability, and tailored selectivity. New research projects focus on expanding its use in fields such as metal recycling, pharmaceuticals, and next-generation energy storage. Startups and established firms partner up with universities to scale green synthesis, hunt for recycling strategies, and understand lifecycle environmental effects. There’s room for regulatory standards to keep pace, guiding best practices in handling, transportation, and disposal. The more researchers explore its possibilities, the better our collective knowledge of what works in real-world conditions and what doesn’t. As more data shapes the discussion—spanning everything from industrial scale to lab benchtop—EMIM-SCN could find itself supporting a shift to safer, more circular chemical engineering.

A Closer Look at This Curious Compound

The world of chemistry keeps tossing up new solutions for old problems. 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate isn’t some household cleaner under your sink—it’s what’s called an ionic liquid, and it’s part of a wave of greener alternatives pushing the boundaries of chemical industry. With this salt, you won’t get fumes rising up or flammable vapors swirling in the air. The liquid stays stable, and that property draws in researchers and companies hungry for a safer way to work in labs and factories.

Tackling Real Problems in Chemistry Labs and Beyond

Many solvents work well, but they leave a mess. Take the classic issue of toxic runoff or heavy volatile compounds polluting the air. 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate dodges those pitfalls because it carries virtually no vapor pressure at room temperature. Lower emissions mean less harm to workers and the environment.

I remember chatting with a friend from graduate school who handled solvents every day. Even with fume hoods, headaches and dry eyes came with the territory. Newer ionic liquids like this one cut down these daily risks—less worry about breathing in harmful chemicals equals more focus on experiments. Researchers reported that these salts dissolve cellulose or other tough biopolymers that normally laugh at traditional solvents. This ability opens doors for recycling plastics or turning plant waste into high-value materials.

Role in Smart Material Design

Scientists lean toward 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate when engineering electrochemical devices. It shows up in fuel cells, batteries, and sensors. Strong ionic conductivity makes it a choice for next-generation batteries, because it helps ions move fast and consistently. The compound also helps separate different chemicals from each other—handy when purifying pharmaceuticals or dealing with tricky separations in industrial processes.

I’ve followed the rush in battery research. Safer electrolytes mean fewer fires in lithium-ion systems and more robust devices for energy storage. This isn’t just about advancing technology; it's about people sitting in a car or carrying a phone that won’t ignite in their pocket.

Green Chemistry and Sustainability

Sustainability no longer sits on the back burner. Regulators and markets reward processes with lower impacts. 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate sets a new direction away from fossil-derived, toxic chemicals. Its recyclability takes some pressure off companies aiming to shrink their environmental footprint. Those in textile manufacturing, for example, use the compound to dissolve and reshape cellulose, spinning up nature-based fibers that shrug off old petroleum ties.

Challenges on the Road Ahead

The price tag and purity scale-up challenge anyone looking to switch their whole operation over. Not every ionic liquid keeps its promise at industrial scale, and some release tricky byproducts or take a lot of energy to produce. Tackling these issues feels crucial if the chemical is to break out beyond specialty labs. Academic collaborations and tighter regulation could push producers for better life-cycle analysis and safer waste management.

Better research funding and partnerships across universities and industry would bring out safer, cost-effective ionic liquids. Open data on environmental risks of any new compound ensures communities and workers stay protected. Step by step, 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate and its relatives reshape modern chemistry—moving innovation a little closer to health, safety, and the world we want to see.

Why Proper Storage Matters

Whenever I deal with chemicals like 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate, common sense and routine matter more than jargon. This compound, known for its role as an ionic liquid, can serve as a handy tool in labs for dissolving other chemicals or running reactions at mild temperatures. Yet, compared to more conventional solvents, it demands a closer look at storage details.

If you put this ionic liquid in a careless spot, it reacts with moisture, air, and sometimes other common substances nearby. Corroded containers, altered color, or odd smells have all come from storage mistakes. These may sound like minor annoyances, but they hint at breakdowns that affect purity and safety. So, a bit of real-world caution goes a long way.

Controlling Moisture and Air

This chemical pulls water right out of the air. In a humid room, you could see the substance change texture or get sticky. Over time, enough water sneaks in to shift its chemistry. I’ve learned to seal these bottles tightly every single time. Screw caps with those Teflon liners work better than anything else I’ve tried. Silica gel packs in the storage area make a visible difference, especially in warm months.

Some users store these ionic liquids in a dry glovebox. That only makes sense when frequent access isn’t needed, or purity runs top priority. For most daily lab settings, a regular desiccator cabinet suffices, provided everyone remembers to swap the desiccant regularly.

Protecting from Light and Temperature

Sunlight and heat both speed up unwanted reactions. In my own workspace, I saw containers left on windowsills turn amber within a few weeks. Color changes often mean less useful product. I keep this material in opaque bottles, stored away from direct light. Refrigeration doesn’t always help and can complicate access, but a cool, dark cabinet offers plenty of protection for weeks or even several months.

Most ionic liquids like moderate, consistent temperatures. Extremes can mess with bottle seals and lead to slow leaks. I found out the hard way after a cold snap forced our heating off over a long weekend. Afterward, more than one cap failed, and we lost some inventory to evaporation. Keeping things at standard storage room temperatures — say 15 to 25°C — avoids those headaches.

Avoiding Incompatible Materials

I learned not to store compounds like 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate near acids, bases, or strong oxidizers. Once, an accidental spill of bleach in a shared stockroom led to ruined bottles, strong smells, and some safety worries. A designated chemical cabinet, properly labeled, solves most of these problems. Even more importantly, everyone in the lab knows exactly where dangerous substances sit, so accidents drop off.

Labelling also goes beyond basic names: adding the date received and the date opened helps plan purchases and use. Unknown shelf lives rarely end well in active labs. For this ionic liquid, replacing bottles within a year keeps work reliable and avoids degraded material that wastes both time and money.

Building Safety Habits

I always tell new lab members not to treat chemical storage as an afterthought. Procedures matter most on busy days, not quiet ones. Talking through the reasoning — limiting air and water contact, keeping things cool and dark, avoiding reactive neighbors — fosters a routine no one skips. As a result, costly surprises and lost time from failed reactions rarely happen. Respect for daily storage goes hand in hand with real chemical know-how.

A Closer Look at the Concerns

1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate doesn’t get much attention outside of chemical circles, but it’s worth taking a hard look at it. Workers in research labs and certain specialty industries cross paths with this ionic liquid more often than most. Folks get used to handling complicated names like this, yet the real question hovers: what’s the risk to human health?

Personal Experience and Real Hazards

I remember handling a range of chemicals in a small lab during graduate school, and each new substance came with its stack of safety data sheets. Ionic liquids like 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate like to boast low volatility. They don’t evaporate into the air easily, so you won’t get the same shock as you would from strong acids or volatile solvents. But breathing easy doesn’t make it safe to let your guard down.

Some published studies and Safety Data Sheets (SDS) for chemicals from the imidazolium family talk about skin and eye irritation after contact. Swallowing small quantities in test animals caused signs of toxicity. Companies label this compound as an irritant. Based on structure, 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate probably behaves similarly. So if a splash lands on skin, expect reddening or rash. Eyes catch the brunt, so goggles matter. Inhaling dust or vapor, rare as it is, leads to coughing or headaches.

Scientific Evidence and Industry Practice

Peer-reviewed studies bring another layer. The Journal of Hazardous Materials published a paper in 2010 covering imidazolium-based ionic liquids that raised concern about their breakdown in the environment and the possible byproducts. Chronic effects remain poorly mapped as these substances haven't gone through extensive long-term human trials. In a world where new chemicals show up on shelves each year, occupational exposure data falls behind science’s sprint. Thiocyanate ions alone are no joke—animal studies link them to thyroid dysfunction if swallowed in high doses, which means caution pays off in handling any substance that can give them off.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) hasn’t handed out specific exposure limits for this particular ionic liquid. This puts the onus on employers and workers to lean on best practices. Relying on gloves, lab coats, and good ventilation makes sense every time.

Balancing Utility and Caution

These chemicals play an important role in applications like advanced batteries, organic synthesis, and separation processes. Researchers praise their low flammability and ability to dissolve tough substances. Safety shouldn’t trail innovation, though. Training matters. Old habits die hard in labs, but reminders on the walls and regular talks about emergency procedures make a difference. Simple moves—like immediately rinsing spills and avoiding bare-hand contact—cut down on risk.

Finding a Path Forward

Manufacturers could help the cause with clearer labeling and up-to-date hazard communication. Transparency builds trust. Companies owe it to everyone who spends their career weighed down by PPE—or worrying about its absence. If organizations commit to replacing high-risk chemicals with friendlier alternatives whenever possible, everyone down the supply chain breathes easier—not just those who handle the raw material. Until we know the full story about long-term exposure, respect and caution remain the tools that matter most.

Grasping the Formula

Looking at 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate, the chemical formula C7H11N3S stands out. In labs, people refer to this compound as [EMIM][SCN]. The [EMIM] part gives C6H11N2+, reflecting the organic cation, and the [SCN]– shows the contribution from the thiocyanate piece. C7H11N3S blends these together as a single salt, found in powder or sometimes viscous liquid form depending on temperature and humidity. This isn’t just any old salt; it’s a product commonly found in the world of ionic liquids, which show promise in next-generation chemistry.

Why Care About This Salt?

Salt chemistry isn't exciting for most people. I once helped a startup that tackled battery recycling, and ionic liquids like EMIM thiocyanate cropped up every week. Their melting points, low volatility, and chemical stability mean researchers look at them for green chemistry. Regular solvents evaporate and pose hazards. These ionic liquids don’t vaporize easily and can often capture or dissolve surprising amounts of metals, making them useful tools in metal extraction, catalysis, and battery tech.

Many folks outside of research don’t hear much about ionic liquids. Still, behind so many devices lies chemistry like this. During metal recovery from electronics, certain parts dissolve only in specific solvent systems—the success of extracting rare elements like lithium or cobalt sometimes hinges on the choice of an ionic liquid. EMIM thiocyanate, with its specific anion and cation, has a knack for complexing with metal ions. Companies now experiment with it in separation processes where water or traditional acids cause side reactions or toxic byproducts.

Risks and Regulations

No chemical gets a free pass. The reality with EMIM thiocyanate is that, despite being seen as part of “greener” chemistry, it’s not risk-free. Exposure can irritate skin and eyes, and the thiocyanate ion isn’t exactly benign in high doses. Labs must use gloves and fume hoods, and local wastewater policies often call for careful collection of residues—dumping isn’t responsible. Poorly managed disposal means possible soil and water contamination, and that’s a headache for communities.

What to do about it? Good manufacturing practices make a difference. Training researchers and workers to treat “green” chemicals with respect helps prevent accidents. Investing in lab safety, waste reclamation, and responsible sourcing—like using thiocyanate derived from lower-impact production—brings improvements beyond the lab. Even students learn early that better chemicals don’t mean shortcuts in safety. I’ve been in labs where shortcuts led to costly spills and cleanups—a lesson no one forgets quickly.

How Chemistry Impacts Society

Chemistry like this plays out in fields most people never see. If lithium-ion batteries become more recyclable, if electronics get lighter or more efficient to produce, ionic liquids could be part of the reason. The impact ripples out: less toxic waste, safer factories, new jobs in advanced materials. By paying attention to the chemical formulas behind the technology, we get a sense of the invisible backbone of so many products that shape daily life and industry.

Taking Stock of the Chemical

1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Thiocyanate serves a real function in specialized labs, especially where ionic liquids stand out for solvent work, electrochemistry, or material synthesis. For those who haven’t worked with this chemical, it doesn’t look all that threatening. No wild color, no smoke—just a calm-looking solid or liquid. My first impression involved curiosity, but safe handling instructions jumped out quickly. Training hammered home how health stays at risk unless every step follows a plan.

Respecting the Hazards: From Skin to Systemic Effects

People new to this compound sometimes overlook real dangers. Skin absorption and inhalation hazards bog down labs far more quietly than old school acid splashes. My skin once tingled even behind gloves when some residue slipped by during benchwork with similar ionic liquids. Some folks reported headaches, others a cough—so the chemical’s toxicity looks mild until the effects hit after exposure. The Material Safety Data Sheet covers this, but habits matter more than documentation in a pinch.

Personal Protective Equipment: No Shortcuts

Working with 1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Thiocyanate always winds back to basics: wear gloves, safety goggles that hug skin, and a proper lab coat. Good ventilation or a fume hood keeps lungs safe. Gloves need chemical resistance—nitrile beats natural latex every time for these tasks. No matter how routine the experiment, treating every session like something could spill or splash keeps chemical burns and absorption close to zero. Eye washes and emergency showers stay prepped, though I never want anyone to use them for this compound or any other.

Storage: Separation Equals Safety

Safekeeping calls for sealed containers—tight cap, no leaks. I always put liquids in a chemically compatible bottle and keep them away from acids, bases, and oxidizers, since improper mixing leads to unwanted reactions or toxic byproducts. Temperature swings don’t help anyone: keep storage cool, dry, and dark. Even humidity changes influence stability, so silica gel packs and desiccators play a simple but strong role. Label everything with the full name, not a shorthand. Skipping a full label may look innocent until another person misunderstands, and that invites accidents.

Spill Control: Fast and Careful Moves

A clean bench lowers the odds, but spills slip through every now and then. I treat every drop as something to respect. Spilled ionic liquids shouldn’t mingle with water or sawdust; cleanup calls for dry absorbents, gloves, and full disposal procedures. All cleanup materials go into hazardous waste, not the garbage. Every bit of training I received rests on the idea that a small spill now can set off much bigger hazards if left unaddressed.

Disposal: No Room for Improvisation

Disposal challenges tie up most time, because ionic liquids stay persistent. Local and international regulations usually block pouring any waste down the drain. My lab routes every milliliter to hazardous chemical disposal, working with vendors trained for these specific substances. Paper logs and witness checks follow every disposal bottle, making sure nothing skips the process. That detail keeps people, waterways, and wildlife out of the chemicals’ path.

Practical Steps: What Keeps People Safe

People stay protected by following routines—training, labeling, double-checking. Trusting instincts helped me, but trusting protocols even more. Skip a glove or fumble storage, the risks turn real. 1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Thiocyanate helps labs push forward, but the only experiments that matter finish with everyone whole and healthy. That’s where good science begins and ends.