Commentary on 1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tosylate: Background, Properties, Safety, and Future Possibilities

Historical Development

Ionic liquids started out as curious oddities in labs. Most folks didn’t spot their potential until the late 20th century. Among the many, 1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tosylate—often called [EMIM][Tos]—earned its stripes because of a delicate balance: it didn’t evaporate easily, it stayed liquid at room temperature, and its chemical stability fit the bill for a lot of bench chemists frustrated by the hazards of traditional solvents. Chemists needed solvents that wouldn’t catch fire, damage lab gear, or evaporate into labs with poor ventilation. Over the last two decades, 1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tosylate caught on for its manageable synthesis and its way of dissolving challenging compounds. Today, it’s common in academic studies on green chemistry and industrial process scale-ups.

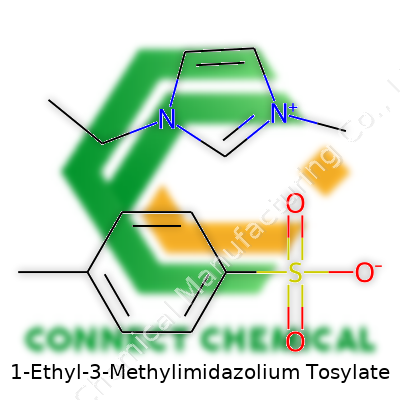

Product Overview

You see it labeled EMIM Tosylate or 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium-p-toluenesulfonate. The core is an imidazolium ring flanked by an ethyl and a methyl group—a motif celebrated for chemical versatility. Its counterion, the tosylate, brings in both stability and strong solubility for specific organic transformations. Labs reach for this ionic liquid to replace toxic chlorinated and volatile organic solvents. Some manufacturers sell it in clear or straw colored bottles, often with a certificate of analysis detailing purity—usually above 98%—since even small impurities can tangle up complicated organic syntheses.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Pour EMIM Tosylate out, you notice its viscosity outweighs water, but it stays pourable at room temperature. It doesn’t carry a pungent odor like the old, hazardous stuff. Boiling rarely becomes a concern, as this ionic liquid resists evaporation even as temperature climbs above 200°C, and it keeps stable up to about 250°C before you see decomposition. It dissolves a big spread of organics and inorganics—especially those with aromatic rings or ions. EMIM Tosylate proves resistant to hydrolysis in basic or mild acidic conditions, which means you don’t waste batches from runaway decomposition. Its moderate polarity balances both hydrophilic and hydrophobic components, which opens up tricky extractions or catalytic cycles.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

The label matters if you care about minor contaminants or end-use requirements. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) or NMR reports on the bottle let you know it meets technical standards, and a CAS number links this batch to published studies. Some suppliers provide water content data, measured by Karl Fischer titration, since trace moisture can mess with sensitive catalytic reactions—typically, under 0.5% water for top-shelf production. The label should mention shelf life and storage conditions: away from light, tightly sealed, at ambient temperature.

Preparation Method

Making EMIM Tosylate starts from imidazole bases. Ethylating and methylating the core ring, usually using alkyl halides, crafts the cation. After purification, chemists react it with p-toluenesulfonic acid. Water-phase extractions and rotary evaporation remove traces of undesired salts and starting materials. The product gets dried under vacuum to punch out last bits of moisture—a step you can’t skip, since leftover water derails many ionic liquid uses. In research labs, smaller-scale syntheses save on costs and allow customization, while industrial producers refine the method for ton-scale output, tracking impurities every step.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

EMIM Tosylate doesn’t just soak up organics—it plays an active hand in many reactions. It can stabilize transition state species in catalysis, making it a backbone for palladium- or copper-driven couplings that otherwise struggle in traditional solvents. Researchers have fine-tuned the structure by swapping the tosylate anion for other sulfonate analogs, or by tweaking the side chains on the imidazole ring to open up solubility or favor specific transformations. Reports show that EMIM Tosylate can even act as a template for assembling nanoparticles, attracting attention from folks who want new battery, sensor, or catalytic materials with finely tuned size or shape.

Synonyms & Product Names

Chemists encounter EMIM Tosylate under labels like 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium p-toluenesulfonate, [EMIM][Tos], or various catalog codes like EMIM-TS or similar. In purchasing, cross-check the supplier’s chemical registry or CAS number—commonly 424701-90-2—which helps prevent mix-ups with structurally similar but functionally different ionic liquids.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling EMIM Tosylate feels much safer compared with volatile solvents, but respecting the chemical pays off. Direct contact with skin or eyes can cause irritation, so gloves and splash-resistant eyewear stay standard. Fume hoods come in handy if you heat it, as byproducts from decomposition aren’t fully mapped. Industry-grade safety data sheets (SDS) provide first-aid steps, fire-fighting options, and leeway for spill cleanup. Disposal guidelines treat ionic liquids as organics, requiring incineration or specialist waste collection. Labs with tighter environmental standards monitor air and water releases, as ionic liquids like EMIM Tosylate break down slow in natural conditions and can build up locally.

Application Areas

You rarely find a single-use for EMIM Tosylate. Electrochemists favor it for batteries and capacitors, thanks to its ionic conductivity and electrochemical window. In organic synthesis, it dissolves both ionic and non-ionic reagents without adding flammability risks to the bench. Some teams use it for extracting rare earth metals from ores, skipping harsh acids, and for making specialized cellulose fibers—where old school solvents would wreck the substrate or produce toxic fumes. Biotech labs use EMIM Tosylate in protein folding studies, since its benign properties maintain activity in sensitive samples.

Research & Development

Universities and industrial R&D labs keep the pipeline moving. A few years back, task-specific ionic liquids looked like the next big thing, and EMIM Tosylate played a core role in screening new anions and cations for catalysts, batteries, and separations. Teams keep publishing on its ability to dissolve lignocellulose, which remains a major barrier for biofuel production. Battery and fuel cell research also churns out papers on doping EMIM Tosylate with metal ions or nanoparticles to boost charge storage or speed up ion transfer. Computational chemistry groups model its solvation abilities, hoping to close the gap between lab results and industrial needs.

Toxicity Research

Early enthusiasm for ionic liquids faded as toxicity data trickled in. Tests on EMIM Tosylate in soil and water samples showed it lingers, and aquatic organisms exposed to high concentrations suffer developmental delays or drop off in reproduction. In humans, long-term skin contact can trigger mild irritation, though documented acute toxicity remains low compared to classic VOCs. Some in vitro studies saw changes in cell growth and metabolic profiles at high doses, flagging a need for more chronic exposure data. Environmental scientists now recommend keeping EMIM Tosylate tightly contained and recycling it to limit release.

Future Prospects

EMIM Tosylate holds a strong position, but the real impact depends on environmental and health findings. Green chemistry commitments push labs and companies to swap out more hazardous solvents, and this ionic liquid fills many roles. If manufacturers invest further in lifecycle and biodegradation research, they can fine-tune EMIM Tosylate for even less environmental impact. Adaptive uses in next-generation batteries, smart textiles, and environmentally-friendly extractants will hinge on this kind of data. Affordable large-scale production—coupled with clear handling guidance—could cement EMIM Tosylate and its cousins as mainstream toolkit essentials. For now, smart application and a critical look at its lifecycle steer the conversation about its place in sustainable science.

What Sets This Liquid Apart

1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tosylate comes up often among chemists who value efficiency and safety. This compound acts as an ionic liquid. Unlike old-school solvents, it stays liquid at room temperature and doesn’t evaporate the moment you take the cap off. For anyone who’s spent time in a lab, that alone can cut down headaches. Safety matters. Reports show that this liquid doesn’t catch fire easily and doesn’t have the notorious fumes that make your eyes water or head ache.

The Draw for Green Chemistry

Interest in green chemistry often starts with swapping out volatile solvents for something less risky. This ionic liquid offers a solution here. With it, scientists get extra stability and lower toxicity without the challenge of containing flammable vapors. The higher thermal stability lets researchers run tougher or longer reactions without worry. Tests in labs have shown less waste generated compared to common organic solvents like dichloromethane or toluene. Calling this liquid a “greener” choice holds water, and a lot of academic research points in this direction.

Making Reactions Work

What surprises many: 1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tosylate speeds up certain chemical reactions. It acts almost like a helper in the room, letting things flow smoother when catalyzing organic reactions. I’ve talked to colleagues who used it for processes like alkylation, etherification, and even some metal-catalyzed couplings. They report clearer products and less cleanup compared to using traditional solvents. A range of published papers supports this, showing higher yields and a reduction in unwanted byproducts.

Role in Material Science and Beyond

This liquid’s odd combination of stability and solubility attracts researchers in material science. They use it to break down cellulose—think plant fibers—for easier conversion into useful bio-based chemicals. This matters because traditional solvents fail at dissolving tough plant matter. Here, the ionic liquid steps in and gets the job done. Biorefineries and research teams focus on this property to save energy and make better use of agricultural waste.

Challenges and Opportunities

High-quality ionic liquids cost more than solvents like ethanol or acetone. For everyday processes in industry, price becomes a sticking point. Handling also brings up practical issues. Disposal and recycling still need better protocols. Toxicity is lower, but you can’t pour it down the drain and call it a day. Regulators and waste handlers pay close attention, rightly so.

Tech startups and chemical engineers keep working on recovery processes where the ionic liquid gets filtered, washed, and reused. Some factory setups now use closed systems, letting them reuse the same batch dozens of times before seeing any significant loss. If industry finds a cheaper way to make or recycle the liquid, the playing field could change quickly. For now, I’ve seen most adoption in research settings or specialty manufacturing where performance justifies the expense.

Looking Ahead

1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tosylate shows what happens when scientists look for better tools instead of settling for what’s handy. As folks look to ditch toxic or flammable chemicals, this ionic liquid draws more eyes—especially where safety and green processes count. The future will likely depend on driving costs down and closing recovery loops, but for plenty of chemists, this liquid has already become part of their toolkit.

Physical Properties: Substance That Stays Put

This compound, often shortened to [EMIM][Tos], grabs attention with its physical quirks. In the lab, you’d spot it as a clear, sometimes slightly yellowish liquid, especially at room temperature. In daily handling, you won’t run into any noticeable odor but it feels viscous—sticky between gloved fingers. It won’t evaporate quickly—volatility just isn’t its thing. This matters a lot for applications where keeping volume consistent counts, such as electrochemistry or chromatography.

The melting point usually sits between 35 and 50 degrees Celsius, depending on purity and moisture content. You heat up the lab a bit, and it shifts from soft solid to liquid rather fast. Its density runs higher than water, so pouring it forms a neat layer at the bottom if you mix with less dense solvents. Water solubility ranks as moderate; expect some interaction, but not a seamless mix with pure water. That’s a double-edged sword: it makes the compound useful in “greener” chemical processes but also means you can’t just flush it out with water if you spill some.

Chemical Properties: The Pull of the Ions

The core feature making [EMIM][Tos] stand out is its ionic structure. The imidazolium cation—built from a five-membered ring with nitrogen atoms—packs a punch by bringing both stability and reactivity. It pairs with tosylate, a sulfonyl-based anion known for stability and low basicity. Together, these ions form a liquid at notably lower temperatures than most inorganic salts, offering science a fascinating playground for dissolving or transporting other chemicals.

[EMIM][Tos] shrugs off many organic solvents; its chemical stability holds steady under a range of lab conditions. It won’t combust easily, making storage less stressful. Still, adding moisture or branched alcohols can change things up fast, affecting viscosity and solubility. That means researchers and chemical engineers need to keep tight control during experiments and manufacturing.

The compound also resists breaking down even when heated above 100 degrees Celsius. This resilience opens the door for use as a reaction solvent or catalyst support in tough settings, such as those needed for certain pharmaceutical or polymer syntheses.

Why It Catches Eyes in Science and Industry

What really draws folks to [EMIM][Tos] is its role in “ionic liquid” research. These substances—non-volatile salts that stay liquid near room temperature—get used to replace more toxic or flammable solvents in extractions or separations. Lower environmental impact is a selling point: fewer fumes, less risk of fire, and easier containment. Chemists who care about sustainability watch materials like this for breakthroughs in green chemistry.

Applications usually revolve around dissolving metals or sensitive organic compounds, but the grip this compound has on metals outpaces many rivals. Some industries now use this property to separate rare metals or recycle catalysts with better yields.

Risks and Practical Steps Forward

Handling safety sits near the top of the list because ionic liquids, while generally safer than many solvents, have unexplored long-term effects once released. Research is ongoing around how [EMIM][Tos] acts in water, soil, or the human body. Until more toxicology data becomes widely available, safe lab protocols and proper disposal keep labs and workplaces out of trouble.

I’ve worked with ionic liquids in a university setting, and the need for gloves, goggles, and ventilated hoods just can’t be ignored—even with substances carrying a “safer” label. Extra attention to spill handling, as well as storage in airtight containers, has become second nature for me and my colleagues.

Finding scalable ways to recycle or degrade used [EMIM][Tos] will help cut long-term environmental loads. Some groups look at microbes or chemical treatments for decomposing residuals. More sharing of real-world toxicity and exposure data would make it easier for regulators and industry to encourage safer use, too.

The key lesson: chemistry moves fast, but responsibility should keep up. This ionic liquid offers clear benefits, but the best future includes new data, diligence in handling, and creativity in cleanup.

The Real-World Side of Lab Chemicals

Working with chemicals every day, you start to realize there’s no such thing as “perfectly safe.” 1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tosylate, often called an ionic liquid, strikes many as a wonder material for dissolving tough compounds or helping with synthesis. What feels invisible are the little choices that keep us all healthy in the lab and outside of it.

Understanding the Hazards

Anyone pouring, weighing, or just standing near industrial solvents learns quickly to pay attention. Chemically, 1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tosylate combines organic cations with a toluene sulfonate anion. It doesn’t carry the flammability risk of common solvents, but that’s far from a blank check for careless handling. Most research points toward irritation of skin, eyes, and the upper respiratory tract if someone mishandles it. Safety Data Sheets published by suppliers tell us direct contact can trigger rashes or burning.

Breathing in fine powders isn’t great for anyone. I remember working once with something labeled “non-toxic,” only to end my day coughing from the dust. Ionic liquids like this don’t vaporize easily, yet accident spills create powders or residues that float in the air and settle everywhere. Even the best-run labs end up dealing with the unexpected mess.

What's at Stake with Exposure?

Researchers have dug into the toxicity story. Findings show some ionic liquids, including ones like 1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tosylate, can cause environmental harm if they make their way into waterways. When disposing of waste, municipal treatment plants rarely filter out complex organic ions. Small spills repeated over time, or one big mistake, could impact local ecosystems. With increased industrial use, risks only grow.

Long-term exposure studies aren’t keeping up with industrial chemistry’s speed. Most published toxicology focuses on acute symptoms or cell-level effects—not what happens after years of handling. Just because reports say “minimal oral toxicity” or “low inhalation risk” does not mean they cover slow cumulative impact, effects on sensitized individuals, or risks to pregnant workers.

How to Stay Safe at Work

Experience matters most around new chemicals. Veteran lab workers check the SDS every time a new bottle arrives. Not every engineer or technician does—especially those used to familiar, routine processes. Regular gloves and splash goggles cost less than a trip to the clinic. Clean-up kits wait in the wings for those inevitable, clumsy elbows.

Local exhaust ventilation trumps generic lab hoods, especially when powders or fine sprays form. Washing hands before leaving the lab makes just as much sense now as it did in chemistry class. Outside of industry settings, hobbyists and small-scale researchers run the biggest risk: safety gear slips down the priority list, corners get cut, and accidental exposures rise. I’ve seen the aftermath of a seemingly minor spill—weeks of careful clean-up, multiple health check-ups, lots of hard lessons.

Practical Steps Forward

We owe it to each other in science, research, and education to foster a culture of asking questions about chemicals like 1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tosylate. Building safer practices comes from learning—and from sharing the times things go wrong as well as right. Manufacturers can step up with clearer hazard labels and transparency around long-term toxicity testing. Institutions can install better training and cross-checks as part of daily routines.

No chemical solves every problem without creating new ones. Treating every novel compound with respect, and sharing real stories about their use and risks, keeps everyone healthier. Sometimes safety is less about avoiding surprises, and more about being constantly prepared for them.

Getting Down to the Basics

1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium tosylate, known among chemists as [EMIM][OTs], stands out as an ionic liquid with a wide range of lab uses, especially in green chemistry and catalysis research. Making this compound in the lab does not require costly equipment or a specialized facility. If you can safely handle organic solvents and acids, you can get it done. Years of running small-scale syntheses have taught me that safety, a clean bench, and attention to measurement make or break the process.

The Honest Truth about the Route

Most chemists use a two-step synthesis: first, quaternize the imidazole ring, and then do anion exchange to get the tosylate version. Here’s how it usually goes. Start with 1-methylimidazole—easily available, pretty affordable—and react it with ethyl bromide. This forms 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide. The reaction proceeds smoothly, especially under anhydrous conditions and with good stirring. Heating the mixture to a moderate temperature speeds things up, but don’t cook it—too much heat can char your product and fill the hood with fumes that sting your eyes. A typical yield falls within 70-80%. All organic synthesis textbooks like March's Advanced Organic Chemistry describe quaternization as a classical procedure.

Once you have the bromide salt, swap out the bromide for tosylate. Dissolve it in water and mix it with sodium tosylate. The key here is using the minimum amount of water for solubility; too much and you’re stuck evaporating forever. The tosylate swaps in, leaving sodium bromide to float away in the water. Separate your product, wash with a bit of cold ethyl acetate, and dry it in vacuum. If you see cloudiness in your product or a brownish tinge, your glassware or reagents probably had some leftovers from earlier runs. Round-bottom flasks need a real scrub between steps, or the purity takes a hit.

Why This Synthesis Matters

The public often overlooks how much industrial and lab-scale advances stem from easier access to ionic liquids like EMIM tosylate. Compared to volatile solvents, EMIM tosylate stays where you put it—no rapid evaporation, less workplace hazard, and fewer headaches for the people nearby. Research from journals, including Green Chemistry and Chemical Reviews, reports on its low volatility and thermal stability, which lets chemists run reactions at higher temperatures and recycle solvent without fuss. Working with hazardous, smelly compounds keeps students away from chemistry. Ionic liquids, with fewer air emissions, can bring real change.

Common Pitfalls and Solutions

Looking back, the biggest trouble comes from poor reagent quality or careless drying. Moisture kills yield. Sodium tosylate likes to clump—grind it as fine as possible and dry overnight before use. Skip on prep and you end up with a brown, gooey mess that’s impossible to purify. Once, rushing late on a Friday, I paid the price with hours of extra column chromatography.

Solving these hiccups starts with vigilance: Keep your chemicals dry, check melting points, and run thin-layer chromatography at each step. It’s tedious but less wasteful than repeating failed reactions. Sharing notes in lab journals about what worked—and what didn’t—helps everyone avoid the same rookie mistakes.

Moving Forward with Caution and Curiosity

EMIM tosylate is a tool that unlocks new research and greener industry practices. The hands-on experience of making it reinforces the basics of chemistry—cleanliness, patience, honest troubleshooting. The most important lesson: respect the process, not just the outcome. People in the lab create new standards by noticing what others miss, turning a tricky synthesis into reliable, scalable know-how.

Direct Risks: Why Proper Handling Matters

Anyone who has worked around specialty solvents like 1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tosylate knows these don’t belong next to basic lab staples. Even a modest spill can cause damage. Breathing in vapors or skin contact can irritate. Long-term, some ionic liquids may present more serious health risks, though data on this specific compound remains limited. I keep this in mind every time I see a half-open bottle in a fume hood.

Letting this stuff mingle freely with water or humidity doesn’t help either. Moisture can degrade it over time or even create byproducts that change its chemical behavior. In my early days at the bench, I learned fast that leaving a desiccator open means the next experiment might go sideways. Keeping 1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tosylate dry, out of direct sun, and away from reactive chemicals cuts down the chances of surprises.

Storing the Compound: Best Practices from the Lab

A solid rule has always been tight sealing. Polyethylene, glass, or similar containers sealed against air work. It helps to tuck containers in a flame-proof, ventilated cabinet, somewhere cool and not in direct path of heating vents or windows. Labs often tag their high-value bottles with hazard stickers reminding everyone about risk of fire, irritation, or chemical incompatibility. Staff meetings repeat the point: keep unrelated acids, oxidizers, and bases in clearly marked, separate cabinets.

A logbook helps with tracking. Besides inventory, an updated log shows old bottles so nothing gets forgotten or degraded in the back of a shelf. Old samples can degrade and build up pressure, complicating cleanup later. A log makes disposal easy for staff and inspectors.

Clean and Responsible Disposal

Pouring this down a drain or tossing it in landfill bins brings long-term harm. The liquid could leach into groundwater and put aquatic environments in trouble. Instead, I package unwanted amounts in the same types of sealed containers used for storage, making sure everything is labeled. Biohazard or solvent waste bags don’t cut it; clearly marked bins specified for ionic liquids, picked up by licensed handlers, go the distance in responsible disposal.

Working with local hazardous waste contractors brings peace of mind. Staff in these companies understand relevant regulations and have technology to treat tricky waste. Some firms employ thermal or chemical destruction, neutralizing potential harm.

For accidental spills, absorbents like sand or universal spill kits trap the liquid. I’ve seen mistakes get more expensive when department heads cut corners on basic spill-response gear. After cleaning, waste and contaminated absorbents need collection for licensed disposal—not just as regular trash.

Community and Regulatory Impact

Regulations in most regions grow stricter each year around chemical disposal. My own experience shows that ignoring protocol can earn heavy fines or, worse, long-term health troubles for workers. Documented procedures raise safety across the lab. This attention protects both people and the environment.

Raising staff awareness is not just a formality; it builds good habits. I’ve seen teams with solid routines prevent incidents by spotting and addressing risks early. In the end, working with careful logging, correct storage, selective disposal, and compliance creates safer research spaces and healthier communities.