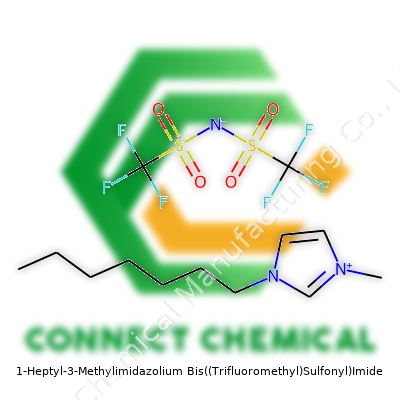

An Article on 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide

Historical Development

The story of 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide, or [HMIM][NTf2] as chemists like to call it, goes back to the early experiments with ionic liquids in the late twentieth century. Back then, researchers kept tinkering with imidazolium cations, figuring out that swapping out the attached alkyl chains could nudge the liquid’s properties in almost any direction. The inclusion of bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide as the anion further widened the range, mainly due to its thermal and chemical stability. Lightbulb moments happened in academia and industry when folks learned that tweaking that heptyl side chain led to a big drop in melting points and stronger hydrophobic behavior. The world started to take these “designer solvents” a bit more seriously, especially as stricter rules pushed traditional volatile organic solvents to the sidelines. Since the early 2000s, these compounds have moved from lab shelves to real-world labs, finding niches in green chemistry, extraction, and even energy storage research.

Product Overview

At its core, 1-Heptyl-3-methylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide balances between stability and flexibility. The molecule brings together an imidazolium ring with methyl and heptyl side chains attached, paired with the hefty NTf2 anion. This combination pushes it far from ordinary salts. Rather than forming crystalline solids, this compound usually lands as a colorless or slightly yellowish oily liquid at room temperature. Instead of sharp, no-nonsense limits for what the substance can do, it offers a wide operating window in the lab and industry. The low melting point, strong chemical resistance, and nearly zero vapor pressure attract those who want safe and reliable performance—even under rough conditions that punier solvents can’t handle.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Chemists and engineers care a lot about what materials can actually do. [HMIM][NTf2] usually clocks in with a melting point around -10°C and doesn’t boil until temperatures soar, due to its almost nonexistent vapor pressure. That low volatility turns into a significant safety advantage. Its density hovers near 1.3 g/cm³, which matters for separation and layering experiments. From an electrical standpoint, its ionic nature delivers moderate conductivity, and the big, floppy anion weakens the hold between ions, reducing viscosity. The hydrophobicity jumps out when someone tries to mix it with water—it tends to stay separate, refusing to dissolve as most salts would. These qualities, shaped by industrial demand and research trends, keep pushing developers to explore new reactions and applications that older solvents simply can’t match.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Any chemist picking up a bottle of this compound expects clear, reliable labeling. Purity often exceeds 99%, and water content sits as low as possible, usually under 0.1%. Common labels include its correct IUPAC name, the CAS number (with 174899-66-2), batch codes, and warning icons referencing acute toxicity and environmental hazards. Those working in regulated industries rely on these specs for compliance with international standards such as REACH in Europe and TSCA in the U.S. Proper labeling and documentation not only keep businesses safe from liability but also help sustain a culture of safety. This material often ships in sealed glass or inert plastic bottles, protecting both the user and the material itself from moisture and light.

Preparation Method

Synthesizing this ionic liquid usually starts with making or buying 1-methylimidazole, an affordable building block that reacts smoothly with 1-chloroheptane or another heptyl halide. The two come together under gentle heating in a polar solvent, producing the cationic salt precursor—often 1-heptyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride or bromide. Next, stoichiometric addition of lithium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide in water or acetonitrile coaxes a metathesis reaction, swapping the anion for NTf2 and precipitating out lithium chloride or bromide as a byproduct. Water washing, careful drying, and filtration finish the job. Many researchers refine the raw product by passing it through silica gel or vacuum-treating it to strip out stubborn impurities. Steps like these directly shape the purity, yield, and physical properties, so small changes can have outsized effects.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

[HMIM][NTf2] resists both strong acids and bases, thanks to its chemically inert NTf2 anion and stable cation. That’s a big reason why people use it as a reaction medium when water would otherwise cause trouble. Its thermal stability also finds a match in catalytic reactions, sometimes even improving yields where traditional solvents lag behind due to degradation. In some cases, the imidazolium ring undergoes functionalization to introduce more complex side chains or reactive groups, which can alter solubility, coordination with metal ions, or even biological compatibility. Chemical modification—say, fluorination of the alkyl chain—moves the goalposts once again, opening new niches in surfactant science, lubricants, or bioseparations. Tinkering with the NTf2 anion, on the other hand, invites even further tuning of hydrophobicity, density, and viscosity.

Synonyms & Product Names

Names pop up based on industry and research context. Most scientists refer to the compound as [HMIM][NTf2], but you might also stumble across 1-heptyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide or 1-heptyl-3-methylimidazolium NTf2. Vendors and catalogues sometimes toss in abbreviations or trade names like HMIM-NTf2, C7MIM-NTf2, or even simple descriptors such as “hydrophobic imidazolium ionic liquid.” CAS 174899-66-2 gives a precise identification, but everyday lab work sticks with the shorter acronyms. This cluster of names can trip up non-specialists, yet anyone with experience picks up the variants quickly enough.

Safety & Operational Standards

Working with ionic liquids like [HMIM][NTf2] calls for real respect in the lab—even as they earn their “green” badge. Spills feel less urgent due to the lack of flammable vapors, but acute and chronic toxicity can’t be ignored. Gloves, lab coats, and splash-resistant goggles come standard. Those handling multi-liter batches suit up with respirators and full face shields out of habit, not just regulations. Waste disposal matters; complex fluorinated anions do not break down easily and need specialized treatment. Most protocols follow the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s chemical hygiene plan, with additions for ionic contaminants and the more exotic risks posed by strong acids or bases. Consistent hazard communication and thorough training keep injuries rare. Suppliers mostly package these liquids in tightly sealed, non-reactive bottles, often with secondary containment to prevent leaks—reflecting an industry segment that’s learned hard lessons from spills and near-misses.

Application Area

The applications draw plenty of interest from both academic and commercial circles. [HMIM][NTf2] regularly stars as a solvent for catalytic reactions that refuse to cooperate with classic organics. Often used in separations, the ionic liquid can drag out precious metals, clean up fuel blends, or split off tricky organics using its unique solubility profile. Electrochemistry labs like its wide electrochemical window, and battery researchers look at ionic liquids as possible replacements for dangerous lithium battery electrolytes. Pharmaceutical labs sometimes use these compounds to extract rare alkaloids, enzymes, or biomolecules without risking denaturation. Out in the environmental sector, [HMIM][NTf2] handles extraction and remediation with less risk of secondary pollution, although attention to toxicity and long-term environmental effects remains vital. At the pilot scale, those interested in energy storage, advanced lubricants, or carbon capture keep running bench trials that hint at a much wider future.

Research & Development

Current research keeps pounding away at the limitations set by cost, toxicity, and recyclability. Chemists run hundreds of structure-property tests, mapping how small changes to the cation’s side chains or the bulky NTf2 anion alter performance in real-world applications. As always, scaling up remains the tricky part—bench reactions that work at 50 mL lose efficiency and purity when stretched to 5 liters. Collaboration stretches across continents, as labs in the US, EU, China, and Japan put their own spins on eco-friendliness, process safety, and recovery after reaction use. Researchers publish on upcycling these liquids, sometimes breaking down old samples with supercritical CO2 or clever combinations of adsorbents. Industry partners push for higher performance in battery and capacitor electrolytes, targeting longer cycle life and lower degradation. Some groups also look at incorporating these ionic liquids into solid supports for supported liquid membranes or sensor technologies.

Toxicity Research

The bright promise of [HMIM][NTf2] sometimes stops short at the question of safety. A handful of toxicology studies show moderate toxicity to aquatic life, often traced back to the stubborn, highly fluorinated NTf2 anion. Chronic exposure in lab animals sometimes links to liver or kidney changes, pushing risk assessments away from large-scale open use. Human exposure data stays rare, but enough parallels exist, thanks to similar imidazolium-based ionic liquids, to support a general approach: minimize exposure, enforce good hygiene, and use closed systems wherever possible. Environmental researchers follow up with soil and water monitoring, looking for long-term effects. Green chemistry advocates keep calling for non-fluorinated replacements or clever recovery strategies. Every new study adds another layer of caution or hope, depending on which way the numbers swing.

Future Prospects

Innovation rarely sits still. Chemists and engineers keep hunting for ways to extend [HMIM][NTf2]'s useful life, lower its environmental impact, and cut costs. Some look at mixed ionic liquids or biodegradeable versions with similar performance. Recycling schemes involving distillation, adsorption, or chemical conversion now attract funding and pilot testing. In batteries, researchers eye next-generation anodes and cathodes that play well with ionic liquids, hoping to crack the barrier for widespread electric vehicle use. Others in pharma want to dial in selectivity for complex separations, where a few percentage points of yield could mean millions of dollars. Green chemistry standards push the industry to tweak molecular designs for lower toxicity or better post-use degradation, while educational campaigns urge chemists to handle these compounds with the care they deserve. The future looks busy, and the only certainty is that every new challenge will demand fresh thinking and deeper knowledge.

A Modern Solution for Challenging Electrochemical Problems

Walking through any chemistry lab these days, you start to see more vials labeled with tongue-twisting names like 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide. It's a long title for a substance doing important work quietly behind the scenes in electrochemistry. People often call these compounds “ionic liquids,” and they’ve started appearing in advanced labs and research publications for good reason.

Why Ionic Liquids Get Attention

Electrochemistry runs into real-world roadblocks. Anyone who's tried to push batteries or capacitors to higher performance bumps up against limits. Traditional solvents break down fast or set off safety alarms due to flammability or toxicity. Ionic liquids, such as this particular one, sidestep these limitations. Their low volatility and high thermal stability mean scientists can run reactions or charge devices without fires or foul air.

Inside High-Energy Batteries and Supercapacitors

Researchers working on next-generation batteries lean on this compound. Its chemical makeup gives it a wide electrochemical window. That means you can crank up the voltage in a battery or capacitor before the solvent itself starts falling apart. Over a decade ago, lithium-ion technology hit a glass ceiling, struggling to charge faster and store more energy. The industry started looking for ways to stretch those limits. Replacing common electrolytes with ionic liquids like 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide makes devices safer and extends their lifespan. Both university labs and big material science firms document fewer thermal runway incidents and more stable cycling. That turns out to mean fewer battery recalls and longer-lasting electronics.

Electroplating and Metal Recovery

Industrial plants now use ionic liquids when dealing with rare and valuable metals. Extracting gold or platinum without toxic cyanide solutions becomes possible. I've watched process engineers get excited about running reactions with less waste and less risk. Traditional chemical baths corrode equipment and spark environmental headaches. This ionic liquid changes that equation, letting companies recover precious metals in a greener way. It even opens up possibilities in recycling, as spent electronics get stripped down for reusable material.

Solving Environmental and Safety Issues

Experience teaches that chemistry projects often fall apart at the safety hurdle. Volatile organic solvents have caused real injuries in labs and factories. Ionic liquids have a low vapor pressure, which means you rarely run into explosive air mixtures or toxic fumes. In my years working with university chemistry clubs, every demo that used industrial solvents had teachers double-checking the fire extinguishers. Swapping in this ionic liquid cuts down on anxiety and gives more room to focus on the science.

Hurdles and Future Steps

No chemical comes with zero drawbacks. Cost still stops many industries from going all-in with these advanced liquids. Some of them build up in the environment and researchers aren't done working out safe disposal practices. It’s key for industry and academia to join forces on scaling up green manufacturing and recycling methods. A few research centers track the full life cycle of ionic liquids, aiming to close the loop on waste. That helps ensure these valuable tools can move from specialty labs to broad commercial use without introducing new problems.

Moving Forward with Confidence

Chemists now carry the benefit of ionic liquids into more challenging spaces, with 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide at the front of the pack. By focusing on solutions that address both performance and safety, the field can support robust innovation in energy storage, industrial metal recovery, and greener chemistry.

Paying Attention to the Label

Anyone who has ever worked in a laboratory, factory, or even a high school classroom probably remembers the shelves lined with bottles marked by tricky names and hazard symbols. These warnings are not for show. Think of nitric acid—touching skin can cause burns, and simply inhaling the fumes leads to severe health problems. Labels serve as the first clue for keeping people and property unharmed. Secure containers and clear signage reduce curious mistakes by people new to the workplace. I learned early on that even the most basic chemicals, forgotten in a messy corner, can trigger panic if a leak starts and nobody recalls what’s inside.

Temperature and Ventilation: No Shortcuts Here

Some substances behave well as long as the room remains cool and low-light. Turn up the heat—literally or figuratively—and problems multiply. Solvents like acetone or toluene evaporate quickly and catch fire even faster. Storing these in a hot room, or near a spark, invites trouble. Good ventilation pulls harmful vapors away from workers. I once heard about a local repair shop struck by headaches and nausea; only after a fire inspector visited did they realize a vent had broken and fumes had nowhere to go.

Preventing Reactions: Separate and Secure

Different chemicals love to react if given the chance—and not in ways you want. Acids sit far from bases. Oxidizers keep their distance from anything flammable. At a college chemistry storeroom, we used thick plastic trays and sturdy locks, making it harder for any accidental spill to join with something incompatible. That storage map took half a day to learn, but days like those make the news when someone skips the instructions to save time.

Moisture and Light: Threats Hiding in Plain Sight

Hydroscopic compounds, like sodium hydroxide, snatch water straight from the air. Left open, they start to clump or dissolve. Peroxides spoil in sunlight, turning dangerous over weeks or months. Some bottles come amber-tinted for a reason, while others demand resealing immediately after use. Keeping certain chemicals at a steady humidity level and protecting them from the sun’s rays can mean the difference between products that last and ones that break down or become hazardous over time.

Training and Emergency Planning

Clear rules and hands-on training go further than any sign or label. My first day in a university stockroom, a supervisor stopped me from moving a sealed bottle by the lid. “One mistake can set off a chain reaction,” she said. Routine refresher sessions keep teams alert. Spills and accidents do happen, but ready access to eyewash stations, spill kits, and well-rehearsed emergency plans prepare people to act quickly. As recent data from the Chemical Safety Board indicates, proper response can prevent loss—human and financial—even during worst-case scenarios.

Improving Practices With Technology

Some companies now track chemical movement with barcodes or RFID. This tech reduces confusion, keeps expiration dates clear, and helps identify what's missing or misplaced. Software alerts managers early if something sits in the wrong place or too long on the shelf, and those alerts nudge everyone to fix small mistakes before they escalate. For smaller labs, even a handwritten logbook creates a safety net—anything is better than relying on memory alone.

What This Chemical Does in Real Life

If you work in a lab dealing with ionic liquids, this mouthful of a chemical often comes into play. People use it for its stability, and it tends to show up in battery research, clean energy storage, and some manufacturing projects. Scientists like it because it doesn’t evaporate fast, and it can help dissolve tough materials. But any time a chemical sticks around this well, it sometimes also hangs on in places you don’t want — like your own body, or the environment outside a cleanroom.

Looking at the Evidence for Toxicity

Any substance with a long, complicated name and fluorine atoms grabs my attention because I’ve seen how these can linger in water and build up in living things. Some other members of this chemical family, especially those with trifluoromethyl groups, have caused fish deaths and problems in cell cultures. According to several studies, the imidazolium part can disrupt cell membranes. Researchers at the University of Amsterdam showed that small invertebrates exposed to similar ionic liquids in water developed developmental issues, and these effects got worse as the molecules got longer or picked up more fluorines.

I once had a colleague get a mild chemical burn after carelessly handling a spill of an imidazolium salt. Nothing dramatic, but a clear lesson to pay attention, especially since toxicity in people has not been well-studied for many newer ionic liquids. The triflimide (that’s the bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide part) makes this compound less reactive with water than older salts but doesn’t clear it of health risks. Some inhalation studies in rodents have caused lung irritation, and some oral exposures in aquatic critters have upset reproduction cycles and enzyme functions. These aren’t headline-making numbers, but research hasn’t kept up with how fast these products are getting adopted. What we know suggests treating them with extreme caution.

Real Risks: People, Labs, and More

Most folks don’t touch these compounds outside the lab, but chemists and engineers do — daily. The most likely trouble comes from skin contact, spills, or accidental splashes. Since this particular liquid doesn’t evaporate away, it’s easy to forget it’s on the bench, waiting to get on your hands. Gloves matter here, and so does proper eye protection. Inhalation risk stays low because of low vapor pressure, but nobody should ever pipette by mouth or heat these in poorly ventilated spots. Waste disposal creates its own headaches. Sewage plants don’t always break these complex liquids down, so they could sneak into rivers and soil. No one wants these compounds moving up the food chain unchecked.

How to Handle the Unknowns

Regulators have started looking at new guidelines, but gaps remain in what we know. Some companies push ionic liquids as “green” alternatives based on how little they evaporate or catch fire. That doesn’t mean harmless — it only means fewer air emissions. I saw a university update its training to recall that “persistent” isn’t always good. A major fix involves better labeling and training for those who use it. Safety data sheets need to keep up with new findings. Research labs would do well to track actual exposures, not just rely on manufacturer information.

Scrutiny should focus on moving research dollars to long-term ecosystem and toxicity studies. Anyone with a hand in process chemistry or R&D can ask questions about disposal and long-term fates before scaling up. We know enough from related chemicals to lean into good habits: avoid contact, contain spills, and never assume newer means safer. Sometimes caution is a better fix than waiting for the data to catch up.

Looking Beyond the Label

Every product story starts at the molecular level. Flip over any package of paint thinner, cough syrup, or fertilizer, and the fine print sometimes lists a chemical name that might look intimidating—words like "acetaminophen" or "sodium percarbonate". Each of these names points to a specific chemical structure. The structure refers to how atoms join together, shape, and interact within the molecule. This arrangement shapes how the product behaves—its reactivity, solubility, and safety. For people working in health, chemistry, or industry, understanding that structure isn’t just trivia; it helps prevent mistakes and protects workers, consumers, and the environment.

Why Structure Matters

From my years working in science education and product testing, I’ve seen real consequences when teams overlook a molecule’s structure. Let’s take acetaminophen. Its structure, C8H9NO2, reveals what happens when you mix it with alcohol or process it in the liver. Miss a functional group—such as the amide group in acetaminophen—and you risk unpredictable reactions. Kids guzzling cold medicine or people working in paint shops rely on chemists getting these details right. If the structure shifts even slightly, safety and effectiveness can change. Small details add up quickly in the real world.

Getting Technical: The Meaning of Molecular Weight

Molecular weight (often listed as "molar mass") tells you the sum of atomic masses in a molecule. Picture it as the molecular “weight on the scale” in grams per mole. Why does this number matter? Consider a pharmacist mixing up a drug, or a wastewater engineer calculating doses for pollution cleanup. Dosing by volume only tells part of the story. Get the molecular weight wrong, the recipe ends up skewed, and results turn unpredictable. Sodium chloride, for example, has a molecular weight of about 58.44 g/mol. Double-checking this number means making sure no corners get cut in production or dosing.

Real-World Safety

Mistakes around chemical structure and molecular weight don’t just stay locked in labs. Some years ago, a manufacturing plant in my town had trouble with mislabeled raw chemicals. Due to misidentification, workers mixed chemicals that reacted together, releasing toxic fumes. Emergency response teams used knowledge of molecular weights to estimate potential hazard zones. Tools like material safety data sheets and chemical registries exist precisely to keep these facts straight and easy to track. Companies must invest in ongoing training, not just to follow regulations, but to foster a culture where safety and accuracy matter to everyone on the floor.

Solutions Lead by Experience

A smart way forward is to require clear labeling, frequent checks, and open channels between manufacturers, suppliers, and workers. Every facility needs easy access to reliable chemical databases such as PubChem or ChemSpider—these tools keep scientists and non-scientists on the same page with clear diagrams and trusted data. Educators must aim for hands-on learning so students see molecular models, not just textbook formulas, turning chemical jargon into something anyone can question and understand.

Facing the Future

With synthetic chemistry playing an ever-larger role in medicine, agriculture, and energy, the number of unfamiliar molecules continues to climb. There’s no shortcut in chemistry—it’s about disciplined attention to detail, a solid foundation in how atoms fit together, and teamwork that puts public safety first.

Understanding Its Risks

1-Heptyl-3-methylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide belongs to a group called ionic liquids. These chemicals, used in labs and some industrial processes, push the boundaries of science. Their benefits include low volatility and high stability compared to traditional solvents, helping to curb air pollution. But whenever I see a long name like this one on a bottle, I remember stories from the lab — gloves, goggles, double-layered waste bins. Too many students treat “green” solvents like water. They aren't water. I once spilled a small amount on my glove; the glove started to feel soft and weak, an early warning that these compounds sometimes sneak through safety gear if you let down your guard.

Potential Hazards

Direct hazards come from strong toxicity data about imidazolium salts. Many break down slowly, persist in the environment, and harm aquatic life. The bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide part adds another twist: fluorinated compounds usually resist breakdown, so once they spread, nature struggles to clean up the mess. Citing a 2023 study in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, even trace releases can show up in water far from their origin.

Why Standard Drains Are Not the Answer

I’ve met more than a few people who try to empty leftovers down the sink, assuming the wastewater plant can just “handle it.” This attitude threatens rivers and even the drinking water supply. Ionic liquids like this one survive the wastewater process pretty well. Flushing them is like giving your local river a dose of something it has never seen before. There's a reason regulations in Europe and the US flag these compounds for special handling—authorities know what a mess they leave behind. The US EPA's guidance treats related chemicals as persistent and potentially bioaccumulative, which means even tiny releases stack up over time and cause damage we’ll all pay for.

Best Practices for Disposal

I've learned to keep any leftover ionic liquids in their original bottles, marked with full chemical names, away from acids, bases, or oxidizers. Labs should not mix this with regular trash or recycling. The next step, one I always tell younger colleagues: Contact your local hazardous waste facility. These centers run incineration at high temperatures—much hotter than a backyard fire or even a school’s autoclave. That extra heat actually breaks the bonds in these sorts of chemicals, instead of letting dangerous fragments linger. Every state or country has a different take on labeling and transport, but the core advice matches across the board: Keep it out of daily waste streams and let trained teams handle the rest.

Encouraging Smarter Choices

It’s easy to forget the downstream effects of what we throw away. News about “forever chemicals” such as PFAS and their links to diseases like cancer has made people realize disposal stories don't end at the lab bench. The best solution still begins with careful planning: Only buy what you actually need for an experiment or process, use it up fully if possible, and keep good records of leftovers. Education beats any top-down mandate. I’ve seen teams cut waste in half simply by setting up one central hazardous chemical logbook and making disposal a shared responsibility rather than a chore handed to the newest person.

Better Harm Reduction on the Horizon

The push for less toxic alternatives matters now more than ever. Some research groups already look for ionic liquids that degrade faster or show less impact if accidentally released. But as long as we use innovative chemicals for cutting-edge science, knowing how to handle and dispose of them is the price for progress. Instead of shortcuts, safe habits and a little humility about what we don’t know will keep both our rivers clean and our neighbors safe.