1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride: An In-Depth Commentary

Historical Development

Early research into ionic liquids paved the way for chemists to challenge traditional solvents, which often came with high volatility or toxicity. Back in the 1970s and 80s, the push to discover stable salts at room temperature led to imidazolium-based ionics, and not by accident. The arrival of compounds like 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride marked a practical turn for industries stuck with stubbornly hazardous or inefficient liquids. This class of salts owes its development to both academic curiosity and growing environmental concerns, as the generation before us realized not all solutions had to be flammable or toxic just to get the job done. As awareness of occupational hazards increased, 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride entered labs and eventually pilot plants, showing that new molecular structures could change more than one sector at a time.

Product Overview

Ask anyone who spends time in synthetic labs about this compound and they will mention not just its role as an ionic liquid, but how much it seems to crop up in processes looking for “greener” alternatives. This imidazolium salt stands out for its combination of chemical resilience and flexibility. Unlike conventional organic solvents, this substance does not evaporate quickly, it mixes with water and polar compounds, and it doesn’t have that sharp, nose-tingling smell most chemists grew up with. People found new ways to use it in electrochemistry, biomass processing, and catalysis. In my own experience working on solvent alternatives, seeing a shift from volatile organics to 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride reminded me how deeply small changes in molecular structure can affect an entire workflow.

Physical & Chemical Properties

This compound comes as a viscous, pale to colorless liquid at room temperature, and its melting point sits low enough for easy handling. It doesn’t ignite under normal lab conditions, which gives anyone working with open heat sources some peace of mind. The chloride anion helps the salt dissolve in water, alcohols, and polar organics, making it surprisingly mixable. The seven-carbon heptyl chain on the cation increases hydrophobicity compared to its shorter cousins, so those wanting to separate aqueous and organic components appreciate this property. In technical contexts, this means less evaporation loss, simplified containment, and often better yields for reactions that stall in other solvents.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Sourcing high-purity 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride means scrutinizing batch reports for water content, halide impurities, and thermal stability. Suppliers mark purity above 98% for advanced applications, testing for trace metals and organic residues. Labeling must mention hazard classifications and handling precautions according to GHS and REACH, especially where skin and eye contact risks stay present. Each bottle usually arrives with certificates for CAS number 171058-17-6, batch analysis, and recommended storage. Poor labeling or carelessness in specification leads to batch inconsistencies that researchers sometimes only discover after days of failed experiments.

Preparation Method

The most common preparation method uses 1-methylimidazole and 1-chloroheptane in a direct alkylation reaction. Heat, stirring, and an inert atmosphere protect the reaction from moisture and side reactions. The process produces the salt directly, with a need for purification steps like extraction, washing, and sometimes vacuum drying. For larger scales, pilot plants optimize yield by controlling temperature and the molar ratios tightly. Missteps in synthesis, such as failing to remove unreacted starting materials or quenching at the wrong moment, hurt the quality and credibility of research that relies on reproducibility.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride takes part in convenient ion-exchange processes, where chloride can get swapped for other anions. This lets chemists tailor the salt to fit solvent, catalytic, or electrochemical needs. It holds up well in strong acid and base conditions, though highly nucleophilic reagents or reducing agents cause decomposition or unwanted side reactions. Side-chain length offers researchers another axis to modify solvent properties, leading them to compare it with analogues like butyl or octyl imidazolium salts. Direct chemical modifications on the cation or anion further extend its use, supporting a spiral of research into designer solvents distinct from the solvents chemists grew up with.

Synonyms & Product Names

Lab catalogs and research papers might call this compound 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride, [HMIM][Cl], or heptyl methylimidazolium chloride. The CAS number simplifies ordering and regulatory tracking. Each supplier assigns a product code—Sigma-Aldrich, Alchem, and Tokyo Chemical Industry offer variants under trade names. Awareness of synonyms matters when reviewing literature or tracking down raw materials. Overlooking a familiar-sounding alternative sometimes costs hours in duplicate ordering or wasted synthesis attempts.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling this salt calls for gloves, goggles, and fume hoods, with an eye on skin and respiratory contact. Even though it doesn’t burn easily, eye splashes sting and repeated skin exposure can dry or irritate. Waste streams containing the chloride anion need separate treatment to comply with environmental standards. Laboratories now keep detailed records tracking operator exposure, storage duration, and spill management plans. While the compound’s low vapor pressure cuts inhalation risks, relying on it means reinforcing basic chemical hygiene and using material safety sheets that actually get read on the bench.

Application Area

1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride surfaces in tasks as varied as biomass conversion, extraction of rare earth elements, catalytic hydrogenation, and even in batteries and solar cells. Biorefineries deploy it to dissolve cellulose and hemicellulose for biofuel production, bypassing limits of water or simple organics. In battery labs, researchers look to its ionic conductivity and thermal stability for next-generation electrolytes. It plays a subtle but key role in many pharmaceutical synthesis routes due to its ability to stabilize reactive intermediates. Shifting from flammable or carcinogenic solvents to this ionic liquid means safer workspaces and an easier job training new chemists. Even so, the up-front cost sometimes discourages smaller or underfunded labs from switching.

Research & Development

Investment in next-generation ionic liquids, especially those based on imidazolium scaffolds, continues to drive journal articles and patents. Recent research looks at structure-performance correlations, environmental impact, and applications in carbon capture—one of today’s most urgent industrial challenges. Universities and startups target modifications on the cation or anion that might cut costs, boost recyclability, and lower ecological footprints. Teams develop supported versions to use in heterogeneous catalysis, and others tweak side chains for use in pharmaceutical clean-up or specialty separations. Discussions at recent conferences show a growing consensus about the need for scalable greener synthesis and end-of-life management to make ionic liquids like this one more than niche replacements.

Toxicity Research

Toxicologists caution that, while these ionic compounds reduce fire risks, they present new questions about long-term contact and aquatic persistence. Initial results show some cytotoxicity in cell lines and slow degradation in soil and water, so disposal and chronic exposure require tighter controls. Regulatory agencies demand more real-world fate data—how much accumulates in waste streams, what metabolites form, and whether breakdown products linger longer than anticipated. In my time working with ionic liquids, I saw safety officers push for better secondary containment and staff training, especially as rumors of stubborn aquatic toxicity began filtering through workshops and safety seminars. Ongoing studies will tell us which molecular tweaks cut down the most serious risks.

Future Prospects

The road ahead looks promising, but not without obstacles. If chemists and engineers solve challenges around large-scale, cost-competitive synthesis and end-of-life management, 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride could see even wider adoption. Green chemistry curricula now introduce this compound to undergraduates, pointing to it as both an advance and a learning opportunity about trade-offs in real-world applications. Hard lessons from earlier solvents guide today’s cautious optimism—solid regulatory oversight, rigorous toxicity testing, and constant dialogue between labs and manufacturers stand as the best way forward. I believe the right partnerships between academia, industry, and government will not only steer ionic liquids toward safer, cheaper, and more sustainable futures—they might also inspire a generation of chemists to think differently about what liquids belong on the bench.

Understanding the Role of Ionic Liquids

You won’t spot 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride next to your household cleaning supplies, but chemists have paid plenty of attention to it. As an ionic liquid, it sits in a family of salts that remain liquid at room temperature. With a bulky heptyl chain and a methyl group sticking to an imidazolium ring, this compound behaves less like salt on your French fries and more like a solvent for some of the trickiest jobs in modern chemistry.

Why This Compound Matters in Research and Development

Researchers look for smarter ways to dissolve, separate, or transform chemicals. This is where ionic liquids like 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride step in. Traditional solvents—things like acetone or toluene—bring problems like flammability and toxicity. In labs, I’ve seen protocols hit a dead end because the solvents evaporated or reacted when no one wanted them to. This ionic liquid barely evaporates at all and offers solid thermal stability. It doesn’t catch fire easily. Scientists and engineers appreciate safety, especially when scaling up reactions.

This compound’s unique structure lets it dissolve both polar and non-polar substances. Say someone’s trying to pull rare metals from old electronics, or separate out dyes from wastewater. Water alone won’t cut it, and old-school organic solvents can make a mess. Researchers have used 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride to create cleaner extraction processes for metals like gold or lithium. In environmental chemistry classes, I came across studies using ionic liquids to pull harmful organics out of industrial runoff, leaving less toxic waste behind.

Use in Electrochemistry and Materials Science

Battery research is hungry for breakthroughs. Since this ionic liquid provides electrochemical stability, it’s a contender for electrolytes in next-generation batteries. Lithium-ion technology has pushed limits but run into safety and longevity issues. With non-volatile electrolytes like this one, you can crank up a battery’s voltage window and keep it from bursting into flames. I’ve seen early-stage projects mix these ionic liquids with polymers, hoping for safer, more stable battery cells in electric cars and grid storage.

The chloride part of the molecule turns out to be valuable in making new materials, too. Electroplating, where you lay down metal coatings, benefits from ionic liquids that hold metal ions without producing clouds of toxic fumes. The goal is thicker, purer, smoother metal layers—without nerve-wracking emission controls. Some companies now explore using this compound to recycle expensive metals from used electronics, cutting mining waste.

Challenges and Solutions

Cost remains the big hurdle. Synthesizing ionic liquids like this isn’t cheap, especially if purity matters (and it usually does). You don’t want leftover reactants or water folding into your lab’s results. Cleaner, greener manufacturing methods need more attention. Open sharing of best practices would help young researchers jump start their work instead of hitting the same speed bumps we did years ago.

Safety isn’t just about fire or fumes; the environmental impact after disposal needs more sunlight. Regulations keep a wary eye on chlorides—many aren’t friendly for ecosystems. Companies serious about sustainable chemistry should track both benefits and post-use risks. Some labs now recycle and reuse ionic liquids, reducing waste and stretching budgets. Ethical choices up front help protect air, water, and people—especially when research ideas graduate into real-world production.

The Bigger Picture

With the push for greener, safer technology, compounds like 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride start getting more time in the spotlight. From batteries that last longer to cleaner mining, these “designer solvents” promise to handle jobs that old chemicals just can’t manage cleanly. As labs and companies fine-tune both their synthesis and disposal, this ionic liquid could shift from a scientific curiosity to an everyday tool for chemists, engineers, and environmentalists alike.

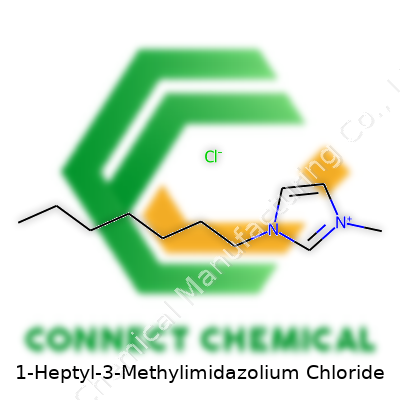

Breaking Down the Molecule

1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride, more casually called [C7mim]Cl, grabs attention for its unique structure. The backbone comes from imidazole—a simple, nitrogen-rich ring. Stick a methyl group on one nitrogen, then swap a hydrogen on the other for a heptyl chain (seven carbons straight), and you get a curious molecule with real staying power in chemistry research. The structure keeps one foot in organic territory and another in the world of salts. That’s not just clever—it offers properties you won’t get by mixing random chemicals.

The imidazolium ring gives the molecule a flat, stable core. The nitrogen atoms in the ring balance electron sharing, and the extra methyl and heptyl arms shift how the molecule interacts with its world. The chloride ion acts as a tough counterweight, attracted by the positive charge the ring holds. On a page, chemists draw it as a five-membered ring with wisps branching off: the lengthy heptyl tail swinging out, the stubby methyl grounded on the other nitrogen.

Real-World Impact and Importance

The arrangement isn’t just for show. Every tweak changes how this salt behaves. Longer tail, like the heptyl group, means lower melting point and less volatility. That makes [C7mim]Cl liquid at room temperature, even though most salts hunker down as solids. That property opens a door: you can use this material as an ionic liquid. Ionic liquids stand out for dissolving loads of stubborn materials (cellulose, for example), running chemical reactions at lower temperatures, and handling electrochemical tasks where water fails.

Safety and sustainability matter more every year. I worked with some traditional organic solvents that leave you with headaches—literally and figuratively. Spills in the lab, disposal challenges, fire hazards, you name it. [C7mim]Cl’s low vapor pressure means less going into the air, and lower toxicity, according to studies like those published in Chemical Reviews and Green Chemistry. That doesn’t let anyone off the hook on safety, but gives research and industry more breathing room, especially when scaling up. It charts a promising course for greener chemistry, swapping out harsh solvents for options that are a little easier on both people and the planet.

Challenges and What Comes Next

The optimism can hit some snags. For every lab excited about [C7mim]Cl, another faces sticker shock. These aren’t bulk chemicals—making and purifying them takes effort and skill. Once used, their fate matters; ionic liquids don’t always break down easily. I’ve seen colleagues chew over waste-handling policies and debate the true “green” status of these compounds. The search is on for ways to recycle or recover these salts, linking chemistry with engineering and policy. In many labs, batch size starts small, but demand could soon outpace supply if solutions prove themselves outside the research world.

1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride delivers a clear lesson: every atom you add or swap in a chemical structure changes the story. In this case, that means more than molecular trivia—it’s a tool for safer reactions, new materials, and a push toward ideas that challenge the status quo of chemistry. Each advance brings its own set of questions, and the field thrives on curiosity and fresh thinking.

Practical Safety Starts with the Container

Anyone who has worked with specialty chemicals like 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride knows that storage goes far beyond screwing on a lid. I’ve seen too many cracked bottles and leaky vials to trust improvised containers. This compound, a room temperature ionic liquid, draws water out of thin air and loves to soak up moisture. Keeping it in a tightly sealed glass bottle kicks off protection right at the start. Lab-grade polyethylene bottles offer an alternative if accidental drops happen often. Either way, skip metal—corrosion risks are not worth the hassle.

Temperature Control Keeps It Stable

From the time I’ve spent in academic and industrial settings, climate control ranks highest on my checklist for any hygroscopic material. Leave this compound on a crowded lab bench, and humidity in the air will sneak inside. Desiccators come in handy, but I always reach for the dry storage cabinet when available. In locations with summer heat or winter chills, aim for ambient room temperature—usually 20-25°C. Below that, crystallization can start; much higher and breakdown follows. Avoiding windowsills and steam pipes isn’t just nitpicking; I’ve watched temperature swings ruin good chemicals overnight.

Shield It from Light and Air

Long days in the lab have taught me that harsh overhead lights and persistent sunlight can start to push some ionic liquids toward discoloration. Many facilities use brown or opaque bottles for sensitive samples. Physically, the color change signals chemistry happening without your permission—often the start of gradual decomposition. I’ve kept 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride on a bottom shelf, away from open air and chasing light, and the shelf life stretches much longer.

Chemical Segregation Isn’t Just for Show

Mixing storage of ionic liquids with strong acids or bases never did anyone any favors. Years in research have taught me to separate chemicals with gusto. Chlorides may react with aggressive desiccants or metals, producing byproducts or even corrosive gases. A clear label offers one level of protection, but a physical barrier—like a dedicated shelf or storage bin—prevents accidental cross-contamination. Even with busy schedules, returning the compound to its proper spot every time means fewer headaches later.

Spill Management: Plan Before You Pour

One clumsy second can leave a sticky mess. Many ionic liquids feel slippery, so spills spread quickly and cleanup grows complicated. Absorbent materials such as sand or fine vermiculite work fast. From experience, a slow mop-up invites stains or skin contact, which leads to irritation. Response kits placed near storage areas show a lab that respects safety, and everyone remembers where to find them after one incident.

Keeping Logs and Lab Culture Strong

Staying organized saved me plenty of times. A logbook tracking lot numbers, receipt dates, and user initials means no guessing about life span or user mistakes. I once avoided repeating a costly mistake because a clear record revealed the history of a questionable container. A team that shares tips, checks expiration dates, and coaches new members lowers the chance of mishaps for everyone. Trust forms a quiet backbone in safe chemical handling.

Real Solutions: Training, Monitoring, Accountability

Regulations and material safety data sheets set a solid foundation. People bring storage guidance to life through regular training, hands-on handling, and spot checks. Reliable storage habits keep expensive chemicals useful and shield staff from top risks. Every safety manual gains real meaning only through daily choices, attention to detail, and a dash of precaution built from experience. Safe storage, after all, means looking out for each other and for the work itself.

Understanding What We're Dealing With

1-Heptyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride steps into the world as a specialty chemical. Chemists and researchers know it well for its use as an ionic liquid—a type of salt that stays liquid at room temperature. Labs use this material for dissolving cellulose, extractions, or as a solvent in chemical syntheses. Its popularity grows along with the rising demand for greener alternatives, but it's not something to handle lightly.

Health and Environmental Risks

Some years working in research labs has made me cautious about new ionic liquids, even when they're marketed as safer options. Academic journals and safety data sheets point to a few problems here. Contact with 1-heptyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride can irritate skin and eyes. Breathing in dust or vapors may irritate the respiratory system. Accidental swallowing spells bigger trouble. This isn’t surprising; many organic salts draw concern for their ability to move through cell membranes and disrupt basic cellular processes.

Studies published by peer-reviewed journals note certain imidazolium-based salts can knock out aquatic life at fairly low concentrations. Tests on small organisms, like Daphnia or algae, provide early warning about what happens if the stuff leaks into a stream. Persistence in water and soil can vary, but these salts break down slowly compared to other chemicals. They might not be the worst, but they don’t vanish quickly, either.

So, anyone working with this chemical ought to pay close attention to waste disposal. Pouring it down the sink invites trouble, and ignoring lab clean-up routines leaves residues that quietly build up. Accidents happen, but regular practice makes them less likely.

Handling and Protection

Having handled similar compounds, I won’t reach for 1-heptyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride without gloves, goggles, and proper ventilation. Safety here isn’t about being dramatic—it’s about lasting health. The fact that you can’t smell or see most solvents doesn’t make them less risky. A fume hood is about the best friend you can have in this situation, along with a kit ready in case of spills.

These protections become more important as more industries look toward ionic liquids for greener solutions. It’s tempting to see "green" labels and treat these as harmless, but chemical properties don’t care about marketing language. Respect for the science matters. Governing bodies in the US and Europe have yet to classify this chemical as especially hazardous, but regulations often lag behind real lab experience.

Better Safety Through Smarter Choices

Choosing 1-heptyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride means picking up responsibility. That means not just using gloves, but teaching others about the risks—even for students or newer researchers who may feel invulnerable. Every bottle of chemical in my own lab is there because it’s essential, and every label includes real hazards, not just vague warnings. If the work doesn’t require this particular salt, look for less hazardous options.

Disposal companies, professional organizations, and local governments all offer better systems for managing specialty chemicals than tossing unwanted solvent in the trash. I make sure everyone in my lab knows the process, and most companies will share advice if you pick up the phone. Thinking ahead saves time, money, and health in the long run.

In the end, 1-heptyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride deserves careful handling and honest respect—nothing less.

Understanding What Purity Means in a Chemical Lab

Labs push for clarity and reliability in every procedure. Working with a compound like 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride, folks want to know it's exactly what it says on the label, not a chemical cocktail. Purity matters—because even trace contamination can flip a whole week’s worth of data upside down. Whether in green chemistry research or advanced battery development, purity isn’t a footnote. It's your unwritten guarantee that tests results tell the right story and your application doesn’t stall on surprise by-products.

Looking at the Numbers: What Counts as Pure?

Most suppliers deliver 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride at a minimum of 98% purity. Professional supply chains use gas chromatography and NMR to check for organic and inorganic oddballs in the batch. Water content gets special attention—often under 0.5%—because ionic liquids suck up moisture like a magnet, which messes with melting points and reactivity. Halide content, including traces of unreacted chloride, also gets measured with ion chromatography, since residual halides can mess with catalysis or electrochemical signals.

In my experience, relying on lesser purity increases troubleshooting. Impurities can hide in reactions, spark strange colors, or slow down ionic mobility. If the product is even a percent off from what suppliers claim, analytical work gets more complicated. The lab wastes time tracing the ghost in the machine instead of moving forward in research. And if you scale up, every little impurity grows into a bigger risk for equipment fouling or regulatory trouble.

Why Good Chemistry Demands Better Quality Control

ISO 9001-certified labs often ask for certificates of analysis, not just purity numbers. They want to see breakdowns for water, metals, and organics. In applications like organic electronics or hydrogen fuel research, even tiny bits of unknowns skew the final product or device performance. A 98% purity specification cuts risk, but high-stakes processes sometimes demand 99% or higher. That means extra purification—vacuum drying, charcoal treatment, or even multiple crystallizations.

I learned this lesson working with ionic liquids for catalysis. Overlooking a fraction of a percent in chloride content led to wild pH swings and flaky yields. Only after digging into the certificate of analysis and pressuring for a fresh, higher-grade sample did experiments start behaving consistently.

Supporting Research Integrity: The Path Forward

One real solution: collaborating closely with chemical suppliers. Setting clear requirements up front, not just accepting whatever comes in a bottle, allows researchers to anticipate problems and save time. More labs should invest in in-house purity testing like NMR and Karl Fischer titration, especially for new suppliers or lots. Well-kept records—tracking which samples came from which batches—help nip unexpected failures before they balloon into lost data.

Genuine transparency, strong quality control, and sharp technical expertise make the backbone of progress in fields that use 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride. Purity isn't a checkbox—it's the quiet foundation for every result you can trust.