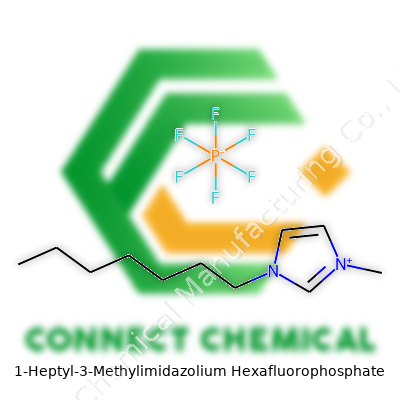

1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hexafluorophosphate: A Deep Dive

Historical Development

Interest in ionic liquids took off in the latter part of the 20th century. Chemists were searching for alternatives to traditional solvents that could limit toxic emissions and flammability. The birth of 1-heptyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate—usually known as [C7mim][PF6]—showed up in the early 2000s as research groups ramped up work on alkylated imidazolium-based salts. By tinkering with the alkyl side chains, scientists could regulate melting points and solubility. Imidazolium cations proved themselves as versatile building blocks for room-temperature ionic liquids. Once hexafluorophosphate anion entered the picture, these compounds quickly gained ground for their stability and manageable handling. The timeline here links directly to broader concerns over green chemistry and a hunger for cleaner, recyclable solvents.

Product Overview

1-Heptyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate shows up as a nearly colorless or pale-yellow viscous liquid, often shipped in airtight vials to fend off moisture. Chemists calibrate it for high purity—often at or above 99%. With performance squarely aimed at specialized roles, those packaging and labeling practices cater mainly to professional environments. Researchers lean on its hydrophobic nature and thermal endurance. What stands out is not the sheer size of its market, but the intensity of its niche applications, from catalysis hubs to physical chemistry labs.

Physical & Chemical Properties

The compound lays claim to a molecular formula of C11H19F6N2P and a molar mass around 346.26 g/mol. Its melting point sinks well below room temperature, while boiling rarely poses any concern since decomposition kicks in before vaporization. The hexafluorophosphate anion keeps things moisture-sensitive, making drying essential before use. Electrical conductivity stays impressive compared to non-ionic solvents—important for electrochemical setups. Water solubility trends low, so it prefers non-polar organics. Stability under air depends on cleanliness and dryness, but most work can proceed on the benchtop if careful. The liquid's density and viscosity allow users to manipulate it in glassware with reasonable predictability.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Suppliers label vials with CAS Number 331717-62-3, batch numbers, and precise purity details. Labeling highlights hazard warnings for both fluorine-containing anions and precautions around potential hydrolysis products. Shipping comes in sturdy amber bottles with airtight caps. Storage guidelines stress cool, dry cupboards away from acids and moisture sources. While these bottles don't take up much shelf space, their contents carry real responsibility—only trained hands should unscrew those lids.

Preparation Method

Making 1-heptyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate requires skill. Most routes start with an alkylation of 1-methylimidazole using heptyl halide in a polar, aprotic solvent under inert gas, yielding the respective halide salt. From there, a metathesis with potassium hexafluorophosphate allows the switch to the PF6 anion, usually in biphasic water-organic mixtures. The resulting ionic liquid phase gets washed, dried, and stripped of starting impurities under vacuum. Final purification stages include filtration over neutral alumina and removal of volatile byproducts. Each step offers a textbook lesson in the value of precision and cleanliness.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Once prepared, [C7mim][PF6] opens doors to a range of chemical manipulations. Researchers swap the PF6 anion for less hazardous options through additional metathesis. On the cation side, the heptyl chain invites further functionalization—introducing polar groups or designing surfactant-like behavior. Even minor changes in the imidazolium ring or its substituents shift the ionic liquid's solvent compatibility and reactivity. In electrochemical systems, the cation can stabilize reactive intermediates, while the anion takes part in phase transfer catalysis. Chemists who spend time hands-on with these materials always watch for subtle color shifts or odor changes, since those can flag the onset of hydrolysis or unwanted side reactions.

Synonyms & Product Names

Product catalogues list 1-heptyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate under several names. Shorthand like [C7mim][PF6], HMIM PF6, or 1-methyl-3-heptylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate pop up across chemical suppliers. Some lab notebooks simplify it to just heptyl-MIM PF6 for brevity's sake. IUPAC conventions yield ‘1-heptyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate.’ No matter the abbreviation, one glance at the structure settles any ambiguity. In busy labs, clear labeling matters more than catchy acronyms.

Safety & Operational Standards

Working with [C7mim][PF6] means keeping risk in mind. Contact with water forms HF, which carries well-documented health hazards. Gloves, goggles, and well-ventilated hoods all feature in proper handling. Spills get dealt with using absorbent pads and neutralizers—skin contact needs quick washing. Disposal means sealing waste for authorized hazardous collection. Each bottle joins a chemical inventory with tracking for audits and emergency response. Past accidents—usually when humidity gets underestimated—push any responsible chemist to double-check storage seals and monitor their environment with care.

Application Area

The range of uses for this ionic liquid stretches well beyond the textbook page. Electrochemistry labs deploy it as an electrolyte in batteries and capacitors, thanks to its broad electrochemical window. In organic synthesis, it lends itself to phase-transfer catalysis and as a medium for transition metal-catalyzed reactions. Extraction chemists use it to separate metals from complex mixtures. Some groups leverage its low volatility for high-temperature experiments, bypassing the limits of traditional solvents. Nanotechnology applications include stabilization of nanoparticles and templating of novel materials. In all these roles, its performance keeps pushing the envelope where traditional compounds taper off.

Research & Development

Innovation around [C7mim][PF6] reflects the ever-changing landscape of chemical engineering. Teams develop new imidazolium derivatives with greater hydrophobicity or unique functional side chains to improve separation selectivity. Analytical chemists study its interactions with biomolecules and polymers, targeting green separations in pharmaceutical workflows. Research into surface-active ionic liquids spins out new uses in microreaction and microextraction. Several papers detail attempts to blend ionic liquids with biodegradable additives, shrinking the environmental footprint. Looking through old journals and recent conference posters, it’s clear that this compound keeps inspiring fresh projects—especially for those hunting for non-traditional reaction media.

Toxicity Research

Health and safety groups take toxicity data seriously, especially with PF6-based compounds. Studies evaluate acute toxicity in aquatic organisms and mammals, watching for systemic effects from both the cation and hydrolysis products. Hexafluorophosphate can hydrolyze slowly in moist conditions; any HF produced poses clearly documented risks to skin, lungs, and the environment. Chronic exposure research is less developed but increasing, especially in Europe under REACH compliance. These studies push suppliers and users toward careful lifecycle management—factoring in not just lab safety, but the long-term fate of waste streams.

Future Prospects

The future of [C7mim][PF6] runs parallel to global shifts in green chemistry and sustainable processes. Industry and academia continue probing for more benign anions and recyclable derivatives to limit risk while keeping performance high. Hybrid materials, where ionic liquids anchor to solid supports, open up new process designs for cleaner separation and catalysis. Software simulations and machine learning now help predict better cation–anion pairings before ever making them in the lab. While regulatory requirements grow tighter worldwide, the lure of non-volatile, tailorable solvents ensures ongoing interest. For those who work with chemicals every day, continuous investment in safer practices, more robust toxicity data, and recyclable systems remain the next steps in keeping ionic liquids both useful and responsible.

Demystifying the Compound

Anyone with an eye on green chemistry or advanced solvents eventually hears about ionic liquids. One that comes up often is 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hexafluorophosphate. Grab a chemistry textbook, and you’ll see this name split into two parts: the cation (1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium) and the anion (Hexafluorophosphate).

The cation is built from an imidazole ring. Picture a five-membered ring, two nitrogen atoms holding hands with three carbon atoms, and then tack on a methyl group at the third position—so that’s your 3-Methyl part. The 1-Heptyl tag refers to a seven-carbon straight chain added to the first nitrogen. Chemists like these tweaks because the chain length shapes the properties: the longer the tail, the lower the melting point tends to slide.

The anion is where things get more exotic: PF6-. Six fluorine atoms circle a central phosphorus atom, giving it a chunky, hearty shape that balances out the cation. This anion doesn’t play well with water, making this salt handy in cases where water tolerance upsets a project.

Why Should Anyone Care?

This isn’t just bookish memorization. These ionic liquids have real impact—biochemists, engineers, and researchers use them in everyday work. They can dissolve a wide slice of organic and inorganic materials that stump classic solvents. This quality pops up in the search for greener chemistry, offering the promise of less-toxic, reusable, and non-volatile alternatives.

A journal study from Green Chemistry pointed out how these substances handle cellulose, usually a tough customer, with far less fuss than the corrosive solvents from decades past. When experimenting with advanced battery tech or pharmaceutical synthesis, their thermal stability matters, too—nobody enjoys runaway reactions or surprise explosions in the lab. Public health and cleaner technologies both ride on these changes.

Skepticism and Safety

Even with these good points, reality insists on a sober assessment. Handling hexafluorophosphate always sets off alarms among environmental scientists. Fluorine is stubborn—hard to break down, likely to linger, and linked to tricky pollutants in waterways near chemical plants. The European Chemicals Agency classifies it as hazardous under certain conditions, pointing toward persistent safety risk unless procedures remain strict.

Some labs jump on the newness of ionic liquids and overlook these headaches. Studies show that imidazolium salts, despite their “green” tag, can sometimes build up in the environment or show low biodegradability, especially when longer alkyl chains or certain anions tip the scale. For someone working on a new cleaning process, it’s smart not to ignore life cycle analysis.

Finding the Middle Ground

Progress means more than swapping one solvent for another—it’s about evaluating the whole process. Chemists started tweaking the alkyl chain or swapping anions with more benign options, like chloride or acetate, to keep performance steady but environmental impact in check. Transparent reporting, open data on toxicity, and strong workplace training all matter as much as the breakthrough itself.

Encouraging companies to invest time and money into safer-by-design chemicals, instead of the lowest-cost shortcut, moves the industry forward. Funding impartial research into breakdown products and long-term safety keeps things real.

New molecules might grab attention with fancy names, but at the end of the day, these details ripple out into manufacturing plants, wastewater, and the health of the people who handle them. The structure of 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hexafluorophosphate tells a story about chemistry innovation, but it also reminds us that good science shoulders responsibility at every step.

Pushing Beyond Ordinary Solvents

Anyone who’s tried to run electrochemical reactions cleanly knows that traditional solvents have their limitations. 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate, often called [HMIM][PF6], brings something different to the table. It’s more than just another exotic compound from the world of chemistry—it opens up new doors in ways everyday lab solvents can’t match. I’ve seen researchers push reactions to higher yields and purities thanks to the unique stability and ionic properties this liquid offers.

Smarter Solutions for Green Chemistry

Green chemistry runs on innovation, not compromise. Since [HMIM][PF6] resists volatility and doesn’t evaporate like most solvents, labs can reduce emissions and lose fewer chemicals to the atmosphere. Beyond environmental benefits, this ionic liquid reduces the need for hazardous organic solvents and helps chemists keep workspaces safer. Teams I’ve consulted with often point to fewer headaches managing waste streams when they use this compound strategically.

Electrochemistry’s Silent Partner

In the world of batteries, fuel cells, and supercapacitors, a reliable electrolyte can make or break device performance. [HMIM][PF6] provides stable ionic conductivity over a wide voltage range, something conventional electrolytes can't always deliver. Battery researchers noticed more predictable charge-discharge cycles and longer lifespan in prototype cells running with this liquid. That matters if you’re chasing energy density or reliability in next-generation materials.

Tailoring Crystal Growth and Material Synthesis

Ionic liquids now play starring roles in synthesizing advanced materials like nanoparticles or organic-inorganic hybrids. Chemists select [HMIM][PF6] for its ability to control solubility, influence nucleation, and shape crystal morphology. Research labs use this compound to coax out new shapes and sizes for particles, trying to fine-tune properties without applying harsh conditions or toxic reagents. In my own work, I’ve watched how a simple switch to this solvent opened pathways to unusual nanomaterial architectures that water or alcohols could never support.

Extraction and Separation That Leaves Organics Behind

Separating valuable metals from waste or extracting complex organic molecules from intricate mixtures gets tough with standard solvents. By choosing [HMIM][PF6], industries can tap into selective extraction properties that beat out conventional approaches. Solvent recovery becomes simpler since the liquid rarely evaporates or degrades under pressure. Many mining studies highlight increased yields and reduced energy costs thanks to these ionic liquids.

Fine Chemical and Pharmaceutical Processing

Chemical engineers see [HMIM][PF6] as a tool for cleaner, more controlled reactions in pharmaceutical and specialty chemical pipelines. Reaction conditions get milder, product purity reaches higher standards, and the number of purification steps drops. Case studies show cost savings stack up when replacing some classic toxic solvents with these alternatives, all without harming product output or regulatory compliance. When the market wants greener, safer drugs, this is one route that checks both boxes.

Paths Toward Responsible Use

No chemical is risk-free, and responsible adoption rests on understanding both benefits and limitations. Research points to the need for careful management and new protocols for ionic liquid recovery and recycling. Labs now invest in closed-loop systems and more robust handling processes to catch spills and recover valuable material. Safer chemistry isn’t a distant goal—it happens step by step as teams embrace new tools like [HMIM][PF6] and build smarter, more sustainable approaches.

Digging Into Purity

Anyone who’s worked in a lab knows how small impurities create big problems. The tiniest slip in purity can mean failed tests, unreliable data, or in the worst case, a patient’s health at risk. Take pharmaceuticals. If a chemical shows a purity below 99%, worries start—will it cause reactions? Will it mix with something else and change how the drug works? Food safety is no different. Stores only stock supplements with high-grade ingredients because consumers have every right to expect safety and value for their money.

Too often, stories of contamination come down to corner-cutting on sourcing or testing. Labs that run LC-MS or GC-MS checks spot those weak points fast. The difference between 98% and 99.9% purity feels like splitting hairs at first, then someone’s batch of infant formula gets flagged, and suddenly the margin matters more than ever.

Clean Storage, Consistent Results

Every tech at my first chemistry job learned quickly—sloppy storage ruins weeks of effort. Powders that sit open in humid rooms turn clumpy. Reactive liquids left without nitrogen shields begin to degrade or take on moisture from the air. Inconsistencies show up in test data, quality teams retrace steps, and sometimes whole production runs get tossed. Over time, I saw patterns. Those who took thirty extra seconds to cap bottles tightly, or label storage shelves properly, found fewer headaches in their workloads. It’s not glamorous, but discipline keeps projects moving.

Each type of substance raises its own red flags. Organics might oxidize if left exposed, so amber vials and low-temperatures give better chances. Biological samples often freeze, not just fridge-cool. Some metals rust or tarnish, so they call for dry boxes or desiccators. Even a plain bag of table salt fares better out of sunlight, away from heat, far from any strong vapor or aerosol.

Why Every Detail Counts

Countless regulations exist for a reason. USP and EP standards outline specifics for things like antibiotic powders or vitamins. Factories that care know their raw materials’ needs by heart. Auditors check not just the paperwork but also the rooms and the air in those rooms. I’ve seen protocols ask for 2-8°C cool storage, taking product straight from delivery to a monitored fridge. Some chemicals demand minus 20°C, or minus 80°C freezers if stability is short-lived. Dryness often ranks just as high. Anything that clumps or cakes signals poor storage.

In the past, legacy systems used handwritten records, which made it too easy to let standards slip. These days, electronic logs and temp sensors put accountability front and center. Everything gets time-stamped—if the alarm sounds at 3 a.m. because a freezer shifted two degrees out of range, a crew member gets the call.

Doing Better, Every Batch

One overlooked tactic: routine training. Even experienced workers can miss steps over time or take shortcuts under stress. I’ve seen simple refreshers prevent costly accidents. Another: cross-checking batches during handovers, not just reading the label but scanning barcodes and sniffing out errors with common sense.

Better initial sourcing pays off. Buying certified pure products keeps the need for complicated testing and recalls to a minimum. If cold storage or drying cabinets cost more upfront, they save money in lost batches and angry customers. Putting resource and thought together gives reliability that holds up to inspection and delivers safe outcomes for users down the line.

Navigating Chemical Innovation and Real-World Risk

Novel chemicals offer breakthroughs in research, energy storage, and manufacturing. Among them, substances like 1-Heptyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hexafluorophosphate—used in ionic liquids—have earned respect in labs and industry. I’ve watched teams across research and pilot plants lean on these ionic liquids for tasks that would frustrate traditional solvents. The advantage: they rarely evaporate and don’t catch fire easily. Yet, “rarely” and “don’t” mask the real-world rough edges. Focusing on the plus side can overshadow what matters most—realistic risks and daily safety basics.

The Devil Is in the Details: What Science Tells Us

On paper, this chemical blend can seem tame. It stays where it’s put, doesn’t ignite under normal conditions, and doesn’t boil away into the air. This has led folks to treat ionic liquids as “green.” Experience, and the research I’ve followed, tell a different story. The structure contains hexafluorophosphate, and that anion can release hydrofluoric acid if it comes anywhere near water—think humid air, sweat, or a spill on the bench. Every chemist I know who’s handled it treats it with a heavy dose of respect. Hydrofluoric acid brings painful burns and long-term bone and organ issues even in tiny amounts.

The cation half, the imidazolium, holds its own issues. Chronic exposure in some cases affected lab animals’ livers and kidneys. The specific heptyl chain introduces possible irritation to the skin or eyes, and longer chains become more persistent in the environment, according to some studies. There aren’t stacks of long-term human health studies on these compounds, so we don’t have a full picture—only glimpses from toxicology papers and accident reports.

Keeping the Work Safe (and People Safer)

Practical safety means learning beyond hazard labels. Any lab or plant handling this compound ought to use gloves, proper safety goggles, and chemical-resistant clothing. My own work taught me to never pipette or pour this liquid outside a fume hood. That means putting a barrier between yourself and invisible mistakes—a drop landing on skin or slowly evaporating in a closed room. Spill kits with calcium gluconate gel stand by, not just in the corner “for emergencies,” but close on the bench, because seconds count if hydrofluoric acid appears.

Ingredient storage gets overlooked. Secure containers, sealed against humidity, cut down much of the risk. Clear protocols, posted in bold print, help remind distracted team members about the possibility of delayed symptoms from exposure. Training refreshers—actual hands-on sessions, not just videos—anchor the lessons people remember. Labs that open up space for “near miss” reporting catch problems early, before someone’s pain or a ruined project reminds everyone of the rules.

Next Steps for Responsible Use

Innovation with potentially dangerous materials always forces a real-world calculation. Workers get the win of new technology, but only if leadership budgets for the proper ventilation, medical monitoring, and staff education. Sharing incident data across the scientific community encourages smarter handling and harder questions about “green” claims. Advocating for more transparent hazard research, and taking time to explain these findings to everyone at the bench, builds a culture where safety isn’t just a policy—it’s a daily habit.

The Puzzle of Dissolving Compounds

Staring at a sample of white powder in a chemistry lab, the big question is simple but crucial: will it dissolve in water, or will you need something like ethanol, acetone, or another organic solvent? The answer shapes everything—from reaction planning to safety precautions, environmental impact, and even the cost of your experiment. Solubility reaches far beyond beakers and flasks; it shapes drug delivery, food chemistry, textile processing, and even groundwater contamination.

Digging Into the Science

Solubility isn’t decided by a magic rule, but the old “like dissolves like” holds weight. Polar compounds—think table salt or simple sugars—break up easily in water, which itself is highly polar. Water owes its dissolving power to the way its oxygen atom hugs electrons, creating partial charges that surround and pull apart ions and small polar molecules. Salts, for example, route their sodium and chloride ions directly into water’s embrace, and off they go, invisible but still present.

On the other hand, organic solvents such as hexane, toluene, or ether are nonpolar or only weakly polar. They surround nonpolar molecules like grease, oil, or wax, breaking them down in a similar way. Large hydrocarbon chains repel water but cozy up nicely with organic solvents, making them the choice for tasks like cleaning up spilled paint or extracting plant oils. This real-world connection plays out in stubborn stains on a shirt or the sticky mess left by tree sap.

Why It’s Not Always Clear-Cut

Every chemist knows frustration when a compound sits at the bottom of the flask, refusing to budge. Plenty of substances don’t fit neatly into “water-soluble” or “organic-soluble” bins. Some, like long-chained alcohols, have both polar and nonpolar parts. They might dissolve in both water and organic solvents, making them heroes in fields like medicine and cleaning. Other molecules, stuffed with bulky groups, just won’t dissolve much at all.

Textbooks teach about hydrogen bonding and dielectric constants, but lab experience tells the real story. Room temperature, stirring speed, particle size—each step shifts things. Crushing a solid or gently warming a solution often opens up new possibilities. That’s a common sight in student labs across the world: warming, cooling, shaking—anything to make that solid disappear.

Health and Environmental Impact

Solubility tells more than just which solvent to use in experiments. If a pollutant dissolves easily in groundwater, the risk spreads over a wider area. Water-soluble pesticides or heavy metals slip quietly into streams and wells. Oil spills, on the other hand, float stubbornly and cling to surfaces, defying easy cleanup. This has led to strict regulations around chemical use and wastewater treatment, with good scientific reason.

What Can Chemists Do?

The wide range of solvents available in today’s labs—from water and acetone to ethyl acetate and even supercritical CO2—gives researchers a toolkit for tackling almost any solubility issue. Manufacturers have started shifting toward greener, safer solvents after decades of toxic spills and worker illness. Solvents like ethyl lactate—derived from corn—offer low toxicity without sacrificing power. Software now predicts solubility using molecular modeling, helping chemists pick the right approach before the first drop is measured.

Understanding solubility goes beyond memorizing rules. It comes from paying attention to how molecules interact, tinkering with temperature, and applying simple logic honed over years working at the bench. The next time a powder dissolves or clumps, that bit of knowledge forms the backdrop for making smarter, safer choices—inside and outside the lab.