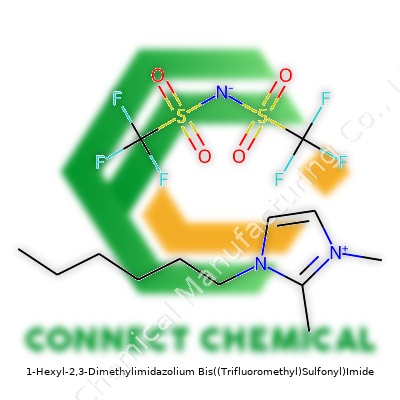

1-Hexyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide: A Closer Look

Historical Development

Chemists started paying attention to ionic liquids back in the 1990s, partly because environmental regulations began tightening on volatile organic compounds. Solutions had to be cleaner and safer. Researchers in Europe and Asia experimented with various imidazolium compounds, hoping to create room temperature ionic liquids that could replace traditional solvents in labs and factories. After years of trial and error, the imidazolium cation paired with bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide (commonly called TFSI or NTf2) caught their interest for its extraordinary stability and resistance to water. By the early 2000s, a few research groups managed to tune different alkyl and methyl groups on the imidazolium core, leading to specialized salts like 1-Hexyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium TFSI. As demand for eco-friendly processes and new battery chemistries grew, its use moved from the lab to pilot projects in industry.

Product Overview

1-Hexyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide is an ionic liquid people often shorten to [C6dmim][NTf2]. Its liquid form stays stable at room temperature, which makes it stand out from most salts that only melt at high heat. Suppliers package it in glass, HDPE, or metal containers, often purged with argon to stop moisture from sneaking in. These bottles usually carry labels with hazard warnings since the product has specific handling needs, especially given both the hexyl and the bis(trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide parts give it strong chemical properties. Researchers and engineers use it for several applications that demand a non-volatile, chemically stable, and thermally robust fluid.

Physical & Chemical Properties

The colorless to pale yellow liquid has a faint, sweet odor and feels slightly oily to the touch. It stays liquid well below freezing, sometimes even down to –10°C, and only boils or decomposes at temperatures above 350°C. Unlike many salts, it doesn’t dissolve in water and usually floats to the top after gentle mixing. You’ll notice it attracts certain organic molecules while repelling water. Its thermal stability matches industrial needs, since many solvents or electrolytes break down long before this one shows problems. It doesn’t conduct electricity like metals, but its ionic conductivity gives it a unique spot in battery research. It refuses to evaporate under normal conditions. The fluorinated sulfonyl groups and the imidazolium core keep it stable in acids and bases, which provides safety in many harsh chemical reactions.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Quality control standards require purity to exceed 98%, verified by NMR and ion chromatography. Trace metals (iron, copper, sodium) get checked down to single-digit ppm since those cause unwanted reactivity or reduce performance. Bottles often display the CAS number along with the UN shipping code. Labels highlight the eco-toxic symbol and state the need for gloves, goggles, and fume hood use. Many suppliers offer product sheets that include melting point (–10°C to –18°C), boiling or decomposition point (over 350°C), density (typically around 1.35–1.39 g/cm³), and detailed spectra.

Preparation Method

The synthesis takes several careful steps. First, chemists alkylate 2,3-dimethylimidazole with 1-bromohexane under controlled conditions. This reaction often relies on mild heating and a base such as potassium carbonate to keep unwanted side reactions low. After extraction and cleanup, the product reacts with lithium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide in water or acetonitrile, which causes the ionic liquid to separate as a clear layer. Rigorous drying with molecular sieves follows since the least bit of water alters viscosity and conductivity. Most labs test every batch to confirm the product’s identity using NMR, FTIR, and mass spectrometry. The process only takes a few hours when done efficiently, but drying and purification need patience and precision.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

This ionic liquid resists chemical attacks compared to earlier, less robust imidazolium salts. Chemical reductions, oxidations, and acid/base treatments all leave the main structure unscathed. Customization comes through swapping out the imidazolium’s alkyl chains or changing the anion. Sometimes, chemists attach more polar or even fluorescent groups to the core, building on the imidazolium ring for special laboratory functions. In industry, people have explored reactions where the ionic liquid acts as a co-catalyst or stabilizer, pointing to its broad compatibility with both organic and organometallic chemistry. The non-flammability and negligible vapor pressure protect against the risks seen with traditional ether or hydrocarbon solvents.

Synonyms & Product Names

You’ll find this product under names like [C6dmim][NTf2], Hexyl-dimethylimidazolium NTf2, or C6DMIM-TFSI. Most catalogs also list it by systematic names — which run so long only specialists use them daily — or shorthand notations that just say “hexyl dimethylimidazolium TFSI.” These varied names come from the chemical supplier’s catalog, research papers, or regulatory databases.

Safety & Operational Standards

While it doesn’t explode or burn like some organic solvents, the material poses hazards if handled carelessly. Chronic inhalation or skin exposure can irritate, and spills create slippery surfaces. Regulations insist on gloves and eye protection, plus proper ventilation. Disposal means collection as hazardous waste, not down the drain or regular trash. The TFSI anion’s stability prevents accidental releases of gas, and no spontaneous polymerization occurs. Industrial buyers assess the full safety data sheet and train staff in spill response. Storage away from acids, bases, and water remains critical for long term safety and performance.

Application Area

One place laboratories use this material is as an electrolyte for lithium-ion and metal ion batteries. The ionic conductivity and almost zero vapor pressure mean battery prototypes stay safer and work at high temperatures. Electroplating, solvent extraction, and catalysis all benefit from its stability and very low volatility. In research, it dissolves both organic and inorganic compounds no regular solvent can handle. In fuel cell testing, its resistance to chemical breakdown under acidic or basic current flow makes it valuable. Analytical chemists use it as a mobile phase modifier in chromatography, opening up new separation techniques. The material also appears in some advanced polymer synthesis as both a solvent and a structure-directing agent.

Research & Development

Research groups around the world keep testing new uses for this compound. Many programs focus on optimizing the ionic conductivity for high-performance energy storage. Some researchers test how adding small metal salts or water tweaks the microscopic structure, hoping for new material phases with exotic properties. Other teams study longer-chain or branched alkyl groups on the imidazolium, searching for liquids that remain stable at even more extreme temperatures or under radiation. Government and university labs in Japan, Germany, and the US often publish work comparing this ionic liquid’s safety and performance to old-fashioned solvents like acetonitrile or DMSO. The market for these substances remains small but expanding every year. As regulations squeeze out more hazardous and volatile organics, interest in greener, tougher ionic liquids keeps growing.

Toxicity Research

Studies of imidazolium NTf2 compounds show mixed results on toxicity. Cell-level experiments report low acute toxicity but possible chronic effects with repeated contact or ingestion. Environmental data points to low biodegradability — the compound persists in soil and water, raising concern about long term pollution. Animal testing shows liver stress and inflammation at high doses, pushing researchers to look for less persistent alternatives. Many countries now demand full toxicity disclosure for commercial sales. Waste handling protocols require containment, stabilization, and high-temperature incineration. Researchers examine metabolic breakdown products, tracking exactly how lab spills or industrial losses move through the environment. Health and safety officers review the literature yearly, updating procedures to reflect the latest scientific consensus.

Future Prospects

As battery makers hunt for electrolytes that operate safely beyond 60°C, this ionic liquid gets more attention. Regulatory pressure on VOCs and persistent solvents force chemical suppliers to pivot toward more sustainable and recoverable fluids. The material’s resistance to fire and decomposition suits the electrification of vehicles, grid backup, and renewable energy storage. Some chemical engineers discuss recycling pathways and closed-loop usage cycles to keep environmental impact low. Universities and research consortia have started screening hundreds of new imidazolium derivatives, seeking to keep or improve performance while lowering toxicity. The combination of safety, performance, and sustainability factors strongly influence where and how this product lands in the marketplace over the next decade.

Understanding Why Chemists Reach for This Ionic Liquid

Anyone who has spent time poking around a chemical lab or reading journal articles about green chemistry recognizes the alphabet soup of ionic liquids. These barely-volatile salts have taken over certain conversations, and among them, 1-Hexyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide stands out for a handful of reasons. It’s often just called [C6C1C1Im][NTf2] for short, which still feels like tongue-twister territory, but nobody in a modern solvent lab would say that this compound is a wallflower.

A Modern Workhorse for Extraction and Synthesis

Researchers look for alternatives to volatile organic compounds as solvents because of issues like toxicity and fire risk. Here’s where [C6C1C1Im][NTf2] steps in. Its ability to dissolve a wide range of substances without evaporating away makes it a choice solvent for advanced chemical extraction, organic synthesis, and separation processes. Oil refiners, pharmaceutical developers, and battery researchers all turn to this compound when they need something that can handle high temperatures and rough chemical environments.

I’ve seen the stuff in the hands of scientists purifying metal catalysts for fuel cells. Chemists separating difficult-to-crack rare earth metals count on its low reactivity and broad solubilizing power. Its structure lets it whisk away solutes without itself breaking down or giving off fumes that drive people from the lab. Its main rival, imidazolium-based ionic liquids with different side chains, often can’t match its mix of stability and solvating muscle.

Chasing Cleaner Chemistry

People want industrial chemistry to cut down on pollution, and the old solvents haven’t been keeping up. Toluene and dichloromethane will clear your sinuses in a hurry, and not in a good way. [C6C1C1Im][NTf2] does not fly off into the atmosphere as easily, and it can usually be recycled for repeated use. It’s clear that as rules get stricter around solvent emissions and hazardous waste, alternatives like this climb closer to routine use.

A real eye-opener came during my own grad student days, when stubborn organometallic compounds simply would not dissolve in classical solvents. We swapped in this ionic liquid, and suddenly the reaction perked up. That single shift cut days of work out of the schedule. I later learned catalysis groups use it for the same reason—sometimes the hardest part is just getting compounds together, and this compound simply lets things mingle.

Environmental Questions and Solutions

No chemical comes without downsides. People point out the fluorinated sulfonyl group can hang around in the environment, raising some concern about long-term effects. Right now, solvent recycling and smart waste management keep those risks down. More research gets published every year on ways to break down or recover ionic liquids after use, using bio-based processes or membrane filters.

Regulation is picking up in places with strong environmental laws. Forward-thinking researchers build this into their approach. They choose ionic liquids only when less persistent alternatives won’t suffice, and they push vendors to supply options designed for easier breakdown. Greener chemistries never come from just one new ingredient, but solutions like [C6C1C1Im][NTf2] keep labs moving forward while waiting for the next breakthrough.

Pushing Industry Standards Forward

In sectors where performance matters more than tradition, this ionic liquid finds a welcome home. I’ve met engineers who swear by it for lithium battery development and others who rely on it to recycle rare earth magnets pulled from old electronics. It’s not always cheap, but it earns its place through resilience and flexibility in sticky chemical challenges. As the push for smarter, cleaner industrial chemistry grows, tools like 1-Hexyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide keep the labs experimenting and industries innovating— leaving those dated solvents on the shelf.

Why It Matters for People and the Planet

Everyday choices about materials and chemicals shape the world outside our front doors. Sometimes, things labeled "green" or "biodegradable" land in our shopping carts and we expect they vanish harmlessly into soil or water. Reality tells a more complicated story. To judge if a compound treats the environment kindly, we have to examine how it breaks down, where it goes after use, and what’s left behind.

Biodegradability: More Than Wishful Thinking

Products marketed as biodegradable often raise high hopes. I remember swapping out traditional plastic bags in my kitchen for something stamped “compostable.” The marketing worked, but those bags lived in the compost bin for months before they broke apart. Biodegradability depends on the right microbes, water, and oxygen. If a material runs into the wrong conditions—say, a dry landfill—it might outlast my old plastic grocery bags.

The US Environmental Protection Agency describes a biodegradable compound as one that microbes can chew up completely, turning it into water, carbon dioxide, and biomass. Compostable items qualify as biodegradable, but only if industrial composters process them the right way. The substance itself isn’t always the enemy; the breakdown conditions deserve real scrutiny. For people worried about waste piling up, this issue shows up every garbage day.

Assessing Real Environmental Impact

Environmentally friendly claims cover more than just how fast something disappears. A truly friendly compound stands out by avoiding toxic leftovers and skipping over the kind of persistence that pollutes soil, rivers, and air. Chemicals like polylactic acid (PLA), a popular bioplastic, come from plant sources and break down faster than petroleum plastics—under specific composting rules. For folks without access to composting facilities, that choice might stall out in the trash.

Some detergents, packaging materials, or cleaning products pile on green buzzwords but slip in substances that harm aquatic life or build up in the food chain. Facts matter. The European Chemicals Agency reviews new compounds for eco-safety, looking for bioaccumulation and toxicity. That’s a model worth following. The golden standard means the end product doesn’t poison or linger, and its resource use does not drain future supplies.

Walking Toward Practical Solutions

Hope for progress lives in clear policies, science-based testing, and honest labeling. Third-party certifications—like the Biodegradable Products Institute or Cradle to Cradle—try to keep claims grounded. If we demand labels show exactly what prerequisites must occur for a compound to break down, then well-intentioned shoppers stop guessing.

Sustainability thrives on details: safe molecular structures, open data on byproducts, transparency about supply chains, and accountability for disposal methods. Instead of leaning just on the word “biodegradable," the next steps involve full lifecycle studies, stakeholder education, and building composting capacity across neighborhoods. For companies, spending time on real research beats spending it on flashier advertising.

Putting Choices Into Action

Every material and compound dropped into our homes presents an opportunity to nudge industry toward cleaner practices. As more people ask tough questions about claims on bottles and bags, change starts happening. Programs that invest in public composting and rigorously tracked environmental testing steer the conversation from surface-level promises to real-world gains. It’s not simple, but most changes that matter start with honest assessment and steady follow-through.

What Matters Most: Physical Qualities at the Core

Some liquids don’t follow the old rules. Ionic liquids draw attention because they stay in a liquid state below 100°C, packing ions instead of neutral molecules. The thing that stands out right away is the low melting point. Where most salts turn rock-hard, many ionic liquids stay pourable and slippery at room temperature. That’s a big shift if you’ve only handled regular table salt in a kitchen.

Many of these chemicals keep to a pale yellow or colorless look, with a pleasant absence of strong odor. Their density sits a bit above water, around 1.1 to 1.3 g/cm³, making them heavier in the hand but still easy to handle. Viscosity breaks away from the expectations of alcohol or solvents—most ionic liquids pour slowly, almost syrupy, and cling to the walls of a beaker.

They don’t jump into the air much, with very low vapor pressure. Leave an open container on the bench, and barely anything vanishes. This changes how folks tackle environmental and lab safety issues since fumes stay at bay.

Chemical Behavior Worth Paying Attention To

Ionic liquids set themselves apart with thermal stability. Most can take heat up to 300°C without breaking down, so high-temperature experiments aren’t off-limits. Their fire resistance earns points in process safety, reducing worries about flashpoints that dog traditional solvent work.

Water usually gets attention. Some ionic liquids pull in moisture from the air, drawing water until they feel oily or even runnier. Working in humid labs calls for airtight storage. Others resist this trick, staying stubbornly dry, which comes in handy for water-sensitive reactions, like Grignard chemistry.

Solubility offers more surprises. Many of these liquids dissolve grease, dyes, or polymers that water can’t touch, yet they barely mix with many organic solvents. This comes handy in extracting valuable substances or cleaning up stubborn stains.

Chemists often focus on what dissolves in what, but ionic liquids flip the script. I learned the value of this the day I saw a stubborn sample dissolve in a drop of room temperature ionic liquid—no heat, no mess. That would fry most plasticware, but these liquids stay mild against glass, steel, and even some plastics.

The structure of the individual ions shapes acidity, coordination to metals, and even electrical properties. Some ionic liquids conduct current, letting them serve in battery research. Tough enough for electrochemistry, but gentle enough to avoid corroding lab gear—you can see why folks keep pushing their boundaries.

The Issues: Access, Price, and Environmental Questions

The promise of ionic liquids gets checked by real-world limits. Many are costly, and large-scale synthesis still carries a heavy price tag. Environmental safety creates hard questions. Although they don’t evaporate, some ionic liquids build up in water—early studies point to tough biodegradation, so disposal rules haven’t caught up yet. Back in university, one clean-up session showed me just how persistent a small spill could be; weeks later, the residue still lingered.

Safe use calls for updated guidelines. Scientists and policymakers need to dig deep into toxicology, focusing on crafting ions that break down safely after use. Companies that come up with greener versions, or biocompatible ones, will steer the future of this tech.

Moving Toward Smarter Use

For now, ionic liquids remain tools best used with respect—not a silver bullet for every problem, but a solid choice for cases demanding heat resistance, fast dissolving, or low emissions. Sharing honest lab results and stronger open data helps lift the whole field. People working hands-on know where the pain points appear, and that feedback shapes the hunt for the next generation of cleaner, cheaper liquids. Paying attention to their real strengths and limits makes good science, and better outcomes for both the industry and the environment.

Respecting the Risks

Every bottle or bag in a lab tells a story, and some demand more attention than others. A harsh-smelling acid, a heavy metal powder, a solvent with a skull and crossbones—they all wave a bright red flag. I remember the way my hands would sweat the first time I opened a container with a symbol I didn’t understand. That uncertainty pushes people to cut corners or work without proper protection. Comfortable routines breed forgetfulness, but the stakes rise every time someone ignores what they know about safety.

Reading the Label—Every Time

Taking a few minutes to read the label and scan the safety data sheet (SDS) can make the difference between a clean lab and a trip to the emergency room. Some substances burn skin, others release toxic fumes, and a few even attack metal or plastic on contact. The SDS explains those risks clearly, and it spells out what PPE (personal protective equipment) keeps your skin, eyes, and lungs out of trouble.

Personal Protective Equipment: Not Just for Show

Goggles and gloves sit on the bench for a reason. Splashes in the eye can leave a person blind, and bare hands soak up chemicals fast. I learned early on to check for pinholes in gloves by blowing them up like balloons. Aprons and face shields seem bulky, but after a classmate wound up in urgent care from a spilled acid bottle, nobody questioned the ritual. Take the time to pick the right material—latex won’t block organic solvents, and cotton lab coats can soak up oil and spread fire. Nitrile or thick neoprene often work for acids and solvents, and flame-resistant coats add a layer of comfort when heating things up.

Ventilation and Storage: Thinking Beyond the Bench

It’s easy to forget the danger lingers long after the bottle is sealed. Solvents evaporate and, without a good fume hood, can turn a lab into a sick ward. I keep a thumb rule: never open anything with a strong smell outside the hood, and never store incompatible chemicals nearby. Bleach and ammonia, for instance, create a gas that empties buildings if they mix. Keep acids on one shelf, bases on another, and flammables away from any heat source. Rusty containers and broken caps are red flags. Replace them instead of hoping for the best.

Preparation for Problems

Things do go wrong. If a spill happens, a delay can do more harm than the original mistake. Spill kits, eyewash stations, and showers need to be easy to spot and keep clear of boxes or carts. Each person in a lab or workshop carries a mental map: nearest exit, location of the first aid box, emergency numbers by the phone. I once froze during a fire alarm because nobody ever practiced a real evacuation. Getting people to act quickly comes down to muscle memory, not a memo tacked on the fridge.

Knowledge Stays Powerful

Training shouldn’t fade after orientation. Coffee breaks often turn into war stories—near-misses count for just as much as the official protocol. Listen, ask questions, run drills that feel awkward, and speak up about broken gear. The cycle of reading, preparing, and practicing never really ends. In my experience, real safety grows from stories passed down, from both triumphs and mistakes, in a place where caution is a sign of respect, not weakness.

Why Storage Matters for Specialty Chemicals

Over the years, I’ve seen labs lose valuable research and businesses burn through budgets just because someone shrugged at proper storage. Any chemist who’s handled ionic liquids like 1-Hexyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide understands that even these so-called “designer solvents” can turn risky if ignored on the shelf. Safe, reliable storage isn’t just a bureaucratic box to tick, but the foundation for consistent performance, product shelf life, and, often, plain old safety.

Heat, Light, and Moisture: The Big Three Enemies

Ionic liquids advertise thermal stability, but the phrase hides a lot of complexity. This particular compound copes with moderate heat, but a closet next to the autoclave or above a radiator is playing with fire. Store containers below 30°C. At room temperature in a well-ventilated place, breakdown products and color changes stay at bay. Sudden spikes or temperature swings can jumpstart unwanted side reactions or shorten shelf life. Sunlight may seem harmless. In reality, prolonged UV can gently nudge imidazolium rings into degradation. Opaque bottles, tucked away from windows, are a good habit that saves headaches down the road.

Humidity spells trouble for lots of ionic liquids. Water sneaks into storage rooms or cuts across messy workstations. This chemical will soak up moisture unless you keep it away from humid environments. Moisture not only dilutes performance, but can also change density and trigger tough-to-clean corrosion. A laboratory-grade desiccator or dry box, ideally with silica gel or molecular sieves, gives peace of mind. Polypropylene or high-density polyethylene bottles keep out most atmospheric water, and tight-fitting caps block the rest.

Labeling and Isolation Reduce Risk

Any shelf worth its salt allows staff to read labels clearly. Out-of-date containers or cryptic glassware stir up confusion. I once found an ionic liquid stashed between flammable solvents and strong acids—this kind of placement courts disaster. Store this compound by itself or with other similar ionic liquids, and always away from reactive acids or bases. Corrosive vapors have a knack for migrating through loose caps, contaminating neighboring bottles and quietly wrecking purity. Spill trays beneath storage containers can catch leaks before they drip down to the floor or shelf, where cleanup becomes expensive and troublesome.

No Substitute for Vigilance

Annual checks on color, viscosity, and labeling catch developing problems early. I advise not just glancing at the inventory but opening bottles in a glovebox or dry room to confirm there’s no waterlogged residue or strange odor. Centralized chemical inventory management systems let research teams keep tabs on age, usage, and batch consistency, promoting accountability and reducing waste. Transparent audit trails matter—not because of paperwork, but because they trace problems in process optimization and manufacturing later on.

Choosing the Right Containers and Training the Team

Glass has always struck me as a safe bet for most ionic liquids, though it’s clumsy for large volumes or frequent use. Polypropylene and fluoropolymer bottles balance chemical resistance with low cost. Never use recycled glass or containers with worn threads—leaks happen fast. Training matters as much as equipment. Both old hands and new staff profit from a quick refresher on transfer techniques, glove selection, and what to do in case of a spill. Chemical hygiene culture grows from clear policies and daily practice, not just posters on the wall.

A Practical Path Forward

Storing 1-Hexyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide shouldn’t be a guessing game. Consistent temperature, dry atmosphere, opaque and sealed containers, and simple organization habits lay the groundwork for reliability. When teams commit to these no-nonsense steps, stability and safety follow close behind—boosting the reproducibility of experiments and the confidence of everyone using the material.