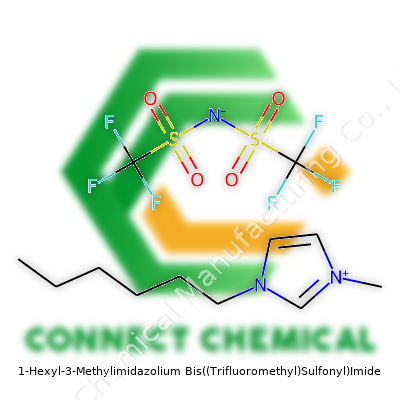

1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide: A Practical Perspective

Historical Development

Scientists pushed boundaries in the late 20th century and found that turning away from volatile organic solvents led to fascinating alternatives. Among ionic liquids, 1-Hexyl-3-methylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide captured attention not just for its structure, but for workable, everyday uses in lab and industrial settings. Researchers learned quickly that tweaking the cation and anion opened up possibilities, and with the hexyl-methylimidazolium backbone, new routes in green chemistry and separation techniques started to open. Looking back, textbooks might not spotlight this specific compound, but talking with researchers today, you often hear stories about their first go with this “hmim TFSI” in early fuel cell or extraction experiments, and how it changed the way they viewed non-volatile, low-flammability alternatives.

Product Overview

This compound usually shows up as a pale yellow to colorless liquid at room conditions. You’ll most often see it offered as a high-purity liquid—lab catalogs tend to advertise purity ranges above 98%. Vendors provide references to stability, since even minor trace water can alter some properties. Chemists call it “hmim TFSI” for short, and nobody pronounces the full name more than once. Sometimes it’s called an “ionic liquid,” but that label doesn’t tell the whole story, since its distinct character comes from the large, asymmetric anion sliding against the oily hexyl tail. With real-world use, you quickly recognize just how different this liquid behaves compared to more basic salts or second-generation imidazolium compounds.

Physical & Chemical Properties

On the bench, this liquid stands apart: it barely smells, refuses to evaporate under a fume hood, and pours with a viscosity that just edges past water. Density hovers around 1.3 g/cm3, so a pipette will tell you if you ever reach for acetone by mistake. Its melting point falls well below zero Celsius; you keep it in a bottle, not a jar. Water solubility feels limited—hydrophobic, yet not as greasy as you’d expect from a long alkyl chain. You find yourself trusting its non-flammable nature in processes that would otherwise raise flags for safety officers. The extended stability up to 400°C makes it valuable in high-temperature batteries and electrochemistry setups. The “TFSI” part provides electrochemical window and low viscosity, while the hexyl-methyl cation fine-tunes polarity, hinting at why it’s selected for specialized separation and electrolyte jobs.

Technical Specifications and Labeling

Heavy-duty labs label this product under names like “1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide,” “HMIM TFSI,” or as the CAS registry number 324049-41-2. You’ll see hazard statements that reference environmental persistence—pictograms sometimes mark this on the label. Most safety datasheets highlight the need for air-tight bottles to block moisture, and packaging leans toward amber glass. Technicians usually check the anion/cation composition with NMR or FTIR before any critical experiment, and suppliers respond fast to QA questions because minor impurities disrupt key applications. Users pay attention to water content—most state less than 500 ppm since ionic conductivity shifts even with light humidity.

Preparation Method

You won’t find this compound naturally occurring, so chemists start with 1-methylimidazole, pushing it through an alkylation reaction by introducing 1-bromohexane. After shaking off byproducts, the next step demands metathesis with a lithium TFSI salt. You get a phase split and then extract the ionic liquid. Lab techs grind through several washes—water, brine, organic solvents—to remove leftover bromide, ensuring chemical purity. Sometimes a short vacuum treatment under gentle heat removes trace water, giving a clear, usable product at the end. For those doing scale-up, the challenge comes with solvent handling, since batch yields dip if trace contaminants sneak in, which affects conductivity or affects sensitive lithium battery systems.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

In hands-on research, this ionic liquid doesn’t just sit there; it plays a role as a solvent, a reaction promoter, or even a supporting electrolyte. You walk into a lab and see it paired with metallic salts—results often include enhanced yields for C-H activation or alkylation protocols. Sometimes chemists add a new tail to the imidazole, shifting selectivity or solubility, or swap out the TFSI for other fluoroalkylsulfonyl groups to get different conductivity or temperature stability. The TFSI anion shrugs off strong acids and bases, so you can run reactions across a wider pH range than you get in water or acetonitrile. Certain photosensitive reactions benefit from the transparent window and inertness, and you can’t deny its role in solubilizing otherwise reluctant organic, inorganic, or even polymeric compounds.

Synonyms & Product Names

1-Hexyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide trades on names across catalogs; “hmim TFSI,” “HMI TFSI,” or “C6mim TFSI” all mean the same thing to chemists who work with it often. Full chemical names get spelled out in patents or dissertations, less so in conversation. Some suppliers abbreviate as [HMIM][TFSI], and occasionally you see it grouped under the “Room Temperature Ionic Liquid” (RTIL) class, but most buyers know to ask by the key cation and anion identifiers.

Safety & Operational Standards

This isn’t the kind of chemical you want to leave sitting uncapped on a bench. The lack of volatility doesn’t mean it’s risk-free. Touching it feels sticky but it doesn’t sting skin the way acids or caustics do, though prolonged contact or inhalation of aerosols brings unknown risks—proper gloves and goggles stay on protocol. Research points to moderate aquatic toxicity, which prompts responsible waste handling and no drain dumping. Once, a colleague dropped a small bottle, and the lack of sharp odor belied how it clung to surfaces—clean-up ran longer than with alcohols or acetone. Even with no immediate human health hazard, labs treat all ionic liquids as controllable risks, since their impact on wastewater and long-term bioaccumulation still needs full understanding.

Application Area

You see this compound show up in real-world scenarios ranging from high-performance lithium-ion battery electrolytes to separation fluids in gas chromatography. Developers keep reaching for it in electrolytic cells and supercapacitors because of the wide electrochemical stability window and low ignition risk. Some green chemistry specialists run catalytic reactions in it due to neat-phase benefits—no need for organic solvents, fewer emissions, less waste. Others make use of its ability to dissolve cellulose or other hard-to-handle biopolymers, hoping for new routes in biomass processing. Analytical chemists value it for conductive media, enabling low-resistance analyses, while process engineers in electrochemical synthesis benefit from its resistance to oxidation and thermal breakdown. You also meet publications detailing its use in pharmaceuticals crystallization, as it subtly switches selectivity for certain polymorphs compared with traditional solvents.

Research & Development

Research with this ionic liquid kept running beyond initial hope. Labs keep pushing its role in new electrochemical devices and advanced purification processes. Scientists adapt its structure, lengthening alkyl chains or attaching new functionalities, in the search for higher conductivity or reduced viscosity. Collaboration between academia and industry drives much of this, leading to commercial electrolytes and radiation-resistant extraction fluids. Grant applications point out its potential to cut CO2 emissions or capture greenhouse gases, and major chemical companies invest in data about its long-term storage, recyclability, and lifetime costs.

Toxicity Research

Toxicity profiles still raise red flags among environmental chemists. Some in vitro studies show moderate toxicity to aquatic organisms, usually connected to the TFSI anion letting loose on water life. Nobody recommends casual disposal—small quantities may escape, but large industrial use pushes for special incineration protocols. In rats and cells, low-recovery rates mean the compound doesn’t move quickly through biological systems, raising questions about longer-term exposure. So far, full zebrafish and Daphnia tests suggest varying degrees of sub-lethal impact, sparking a race to develop greener, more degradable analogs that won’t stick around in rivers or groundwater.

Future Prospects

With the world looking closer at climate change, more energy-dense batteries, and sustainable manufacturing, niche ionic liquids like this one find themselves at a crossroads. Engineers want to swap out volatile solvents, moving to stable, reusable electrolytes for safer, longer-lasting energy storage. Pharmaceutical manufacturers push for “evergreen” solvents, ones that won’t end up downstream. Researchers continuously adapt the structure, combining elements of the imidazolium ring with renewable feedstocks or blending in task-specific functions for CO2 capture, water treatment, or targeted drug delivery. The pace of data collection on toxicity and environmental fate sets the stage for regulation and best practices, moving this compound from scientific curiosity to potential linchpin of green chemistry and next-generation technology.

Understanding the Role of Ionic Liquids in Industry

Some chemicals never attract the public eye, but those working in labs or manufacturing move a little closer every day to them. 1-Hexyl-3-methylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide, known to chemists as [HMIM][NTf2], pops up in journals and at industry tables because of what it can do. People use it behind the scenes but reap the rewards on a much larger scale.

This compound falls under the family of ionic liquids, a group that gets people in chemical engineering excited. You won’t find [HMIM][NTf2] in a kitchen or on a grocery shelf, but try to make new batteries, process biofuels, or get better results from a difficult synthesis, and you might run into someone pouring it.

From Lab Curiosity to Practical Tool

In chemical research, folks care about solvents—the liquids that help dissolve, mix, extract, or transform other materials. Most solvents catch headlines only for their hazards or regulations, but ionic liquids like this one broke the mold. Unlike classic solvents, [HMIM][NTf2] doesn’t evaporate easily and rarely burns, so people can work with it under less stress about fumes or fire. This property alone leads to safer workplaces. The low volatility isn’t the only reason teams reach for it; the molecule’s shape and electrical charge let chemists carry out reactions that would stall in water or old-school organic liquids.

Battery makers look for electrolytes that don’t catch fire as quickly as the ones used in so many phones and cars. [HMIM][NTf2] shows strong thermal stability and carries charge well. More manufacturers in Asia and Europe test it for use in lithium-ion and other cutting-edge batteries. Better storage means more efficient electric vehicles and renewable energy storage. My time spent visiting a battery lab hammered home why researchers turn to it—less time managing cooling equipment and more time testing results.

Green Chemistry and the Environment

Many folks see green chemistry as a buzzword, but workers in refining and recycling live with its real challenges. Petroleum and fine chemical industries chase better extraction tools, and this ionic liquid delivers. The fluorinated sulfonyl groups help separate metals in ways traditional solvent systems can’t, reducing waste and sometimes lowering water use. Pilot projects with rare earth elements and spent electronics recycling have tested it, aiming to ease the strain on the supply of metals needed for electronics.

A standing challenge comes from the persistent fluorine atoms in the molecule. Many in the environmental health community worry about accumulation—if these liquids wind up in water, the impact could last. Chemical engineers and green chemists know they can’t ignore this. Some propose closing the loop: recycling the ionic liquid after each process run. Others look for similar compounds that break down faster in nature, aiming to balance performance and long-term health.

Charting a Way Forward

Using [HMIM][NTf2] works best when teams separate excitement from blind faith. It brings value in safety, energy tech, and extraction. The next step means keeping an eye on what happens after use and working in step with environmental chemists. Forward-thinking labs start with research but keep results tied to better health and a cleaner world for the next round of technologies. The reality of each choice—handling, disposal, product lifetimes—counts more than ever before.

Personal Protective Gear Makes a Difference

Let’s talk personal experience: the one time I didn’t double-check my gloves, I paid the price with a burning sensation that lingered for hours. Gloves, goggles, and a well-fitting lab coat take just seconds to put on, yet they block direct skin contact with harsh liquids. The right kind of gloves matter. For corrosive acids, nitrile or neoprene stands up better than the disposable latex pairs sold at the local market. Always check the safety data sheet for a matching glove material.

Proper Ventilation Is Non-Negotiable

Every time I’ve walked into a poorly ventilated room, my eyes started to sting almost immediately. Chemicals like ammonia or strong solvents produce vapors that float around, and a standard open window doesn’t cut it. Fume hoods or mechanical exhaust fans pull those invisible hazards away. These don’t just help your lungs—they protect everyone in the space. Industrial hygiene studies point to reduced workplace illnesses in labs and factories that maintain good airflow compared to those who skip this step.

Labeling and Storage

Mislabeled bottles nearly caused a disaster more than once in my undergrad days. Mixing containers and skipping labels saves a few minutes, yet can create headaches for weeks. Use a permanent marker, write the exact name, and keep containers tightly closed. Store chemicals with others from the same family—acids away from bases, flammables away from oxidizers. Reports show that mixing incompatible chemicals starts fires and releases gases in less time than people expect. One survey by the CDC found that almost 40% of lab accidents stemmed from poor labeling.

Mindful Handling and Spills

People get confident, pour too quickly, and cause splashes. Take it slow and pour carefully, especially with strong acids or caustic substances. Spill kits should always be in reach: neutralizing powders, absorbent pads, and a sturdy dustpan work wonders. Trained teams can clean up major incidents, but prompt first steps—like using spill pads and ventilation—prevent small accidents from growing into emergencies. The worst mistakes seem to happen when folks ignore the “what if” scenarios and don’t know where the spill kit sits.

Emergency Routines Save Minutes—and Lives

Eyewash stations gather dust in some corners, but I remember a classmate who avoided permanent eye damage because he knew exactly where one was and didn’t hesitate to use it. Know evacuation routes and keep the emergency numbers posted in plain sight. Regular drills beat panic every time. In moments when seconds matter, muscle memory trumps the neatest written procedures.

The Value of Training and Respect

No online course can match a day in the lab, hands in gloves, eyes open to risk. Comprehensive training, paired with real stories of near misses and lessons learned, shape habits that stick. Younger trainees pick up more from seeing an experienced colleague handle a hot beaker safely than from a wall of text. OSHA guidelines emphasize training and review for a reason—most chemical injuries come not from deliberate carelessness, but from skipped steps and overconfidence.

Real Solutions Go Beyond Checklists

Staying safe starts with simple choices: using the right gear, labeling every bottle, handling chemicals with care every time, and understanding the risks. Everyone in a shared space holds some responsibility for watching out for hazards and flagging shortcuts before accidents happen. I find that teams who look out for each other cut down on mistakes and build trust—there’s no substitute for real accountability. Chemical safety grows from these straightforward habits, making the workplace safer for everyone involved.

The Roots of Chemical Identification

Every chemical compound carries a signature that scientists call a formula. This formula does not just tell you what atoms are present; it lays out the exact count of each one. Common table salt, for example, goes by the formula NaCl, which stands for one sodium atom and one chlorine atom combined. Knowing this, anyone can picture salt on a deeper level than what pours from a shaker.

My introduction to chemistry came in a high school lab, armed with a battered textbook and mismatched safety goggles. The periodic table sprawled across the wall showed a world of patterns. I learned that the chemical formula of a substance isn't just for experts—it’s a message about structure and reactivity. Imagine you’re mixing vinegar and baking soda. The fizzing and bubbling aren't magic; they're the result of a reliable relationship between acetic acid (CH₃COOH) and sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO₃). The reaction makes carbon dioxide gas, water, and sodium acetate. A string of letters and numbers tells you so much more than a product label ever could.

The Importance of Molecular Weight

Molecular weight or molar mass takes things a step further. By adding up the atomic masses of each element in a compound, you get a number—the weight of a single molecule compared to one-twelfth of a carbon-12 atom. This calculation tells a chemist how much of a substance to use, especially during experiments or manufacturing. Get the math wrong, and you throw off entire batches.

Once, I spent hours counting out powdered citric acid to balance a home-brewed cleaning solution. Turning to the molecular weight gave me clarity. Citric acid has the formula C₆H₈O₇. That means six carbon atoms, eight hydrogen atoms, and seven oxygen atoms. By looking up each atomic mass—carbon at around 12, hydrogen close to 1, oxygen about 16—I pieced together the total: around 192.12 grams per mole. Suddenly, my measurements grew accurate. Mistakes became rare and results predictable.

Why Accuracy in Formulas and Weights Matters

At labs, at factories, in classrooms, accuracy isn’t just for perfectionists—it safeguards health and sometimes lives. Medical researchers look at a drug’s formula before it ever touches a human body. Hospitals don’t risk patient safety on a guess. Pharmacies double-check calculations of active ingredients because even a small error in molecular weight could impact treatment.

Food producers must follow formulas for preservatives and vitamins to ensure each batch delivers the right amount. Regulatory agencies set rules based on chemical formulas and weights, and they audit results to protect the public. These actions shape the world right down to the contents of your kitchen and your medicine cabinet.

Finding Solutions and Building Trust

Technology helps, offering databases where chemical names, formulas, and molecular weights live side by side. Awareness and double-checking have become part of my routine. Every student, scientist, or hobbyist should use reputable resources like peer-reviewed journals or government portals. Experience has shown me that shortcuts lead to confusion. Confirm every formula by cross-referencing with trusted industry or academic databases. When in doubt, ask another professional. Honest science grows from careful habits—attention to detail and transparent sharing of information.

To make the most of chemical knowledge, build a habit of checking formulas and molecular weights before acting. This simple step can prevent accidents, support good results, and build the trust that science depends on.

The Importance of Solubility

Solubility often gets overlooked until a recipe flops, a medication doesn’t dissolve, or paint refuses to blend. Once, during a summer chemistry class, I tried to mix aspirin tablets into juice as a quick fix for a migraine. They stubbornly clumped at the bottom—a clear lesson that not everything blends effortlessly with water. In the world of chemistry and products, solubility shapes shelf life, smooth skin creams, and the difference between effective medication and bitter residue.

What Solubility Tells Us

Solubility describes how well a substance mixes with a liquid. A substance that blends in with water is hydrophilic, a term every pharmacy student knows. Many salts and sugars love water, breaking apart and disappearing from view. Table salt dumped into a cup dissolves almost instantly, a kitchen triumph I used to take for granted. On the other hand, substances like oil turn water cloudy, swirling separately. No matter the stirring, salad dressing always separates again—oil defies water's embrace.

Products that skirt water often dissolve well in what scientists call “organic solvents”—liquids such as ethanol, acetone, or hexane. These aren’t just lab standbys. Nail polish remover, paint thinners, and perfume ingredients all call these solvents home. Someone might treat a wine stain with club soda (a classic water-based solution) but reach for acetone to tackle nail polish.

Why This Matters

The ability of medicine or food color to dissolve in water or in an organic solvent changes the way people use and trust those products. Most over-the-counter medicines intend to dissolve in the stomach, delivering relief fast. If a drug resists water, it needs a different formula—a challenge that once tripped up a cold medicine I bought, leaving gritty bits stuck in the bottle. Creams that blend smoothly bring comfort, while those staying chunky prove frustrating. I remember slathering on sunscreen at the beach and noticing uneven coverage. That grainy feel came from poor solubility, turning a necessary product into a messy annoyance.

In addition to personal trials, environmental effects deserve attention. Many garden pesticides designed for water can drift into streams, harming fish. Water-insoluble products might last in soil, affecting crops and the bugs that help them. Clean-up, cost, and safety all spin from these tiny decisions about solubility.

Improving Solubility for Better Results

Researchers always hunt for new tricks, blending science and creativity to tackle solubility problems. Nanotechnology, which makes substances super small, helps grind powders so finely they disperse more easily, especially in medicine. A pharmacist once showed me how breaking a tablet down with a mortar and pestle speeds up its action for patients struggling to swallow pills. Adding side groups to molecules or combining them with another agent are two strategies chemistry labs turn to regularly. Even food scientists get creative—using emulsifiers (like lecithin in chocolate) to encourage cocoa butter and cocoa powder to become friends in milk.

For consumers, this means looking beyond packaging. Those ingredient lists and warning labels signal how the product will behave. Will it wash away under the tap, or survive the rain? Will that stain lift with soapy water, or need something stronger? These questions reach beyond science into kitchens, clinics, gardens, and garages—reminding us how the chemistry of solubility shapes more of daily life than we realize.

The Risks Behind This Chemical Compound

1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide doesn’t sound like something found in a typical workday, but for those in chemistry labs or industrial settings, this ionic liquid pops up more often than you might expect. Handling and storage get overlooked by newcomers eager to run experiments or production batches. In the early years of my research, I watched colleagues push bottles of new chemicals onto any available shelf with barely a glance at the label.

Skipping steps leads to ruined materials and, in serious cases, hazardous situations. This particular compound, known for low volatility and non-flammability, brings a false sense of security. It rarely evaporates, so you won’t smell trouble coming. Instead, it creeps up slowly—through water absorption, slow decomposition, or silent corrosion of nearby metals. That makes storage choices a problem worth real attention.

Practical Storage Ideas Learned the Hard Way

During my graduate work, a shared chemical fridge turned into a science experiment itself. Quick fixes ended badly: water got in, labels fell off, crystalline deposits grew around the cap. Over time, I learned to store these ionic liquids in tightly sealed, air-free containers. Even though this compound resists breaking down in air, it still reacts to moisture. I always looked for visible changes or a strange texture—never ignore cloudiness or residue. Lab guidelines point out that even small amounts of water speed up hydrolysis, and that leads to impurities in future experiments.

Keeping Things Cool, Dry, and Organized

Chemicals like this feel stable, but subtle changes ruin batches or mess with results. Cool storage slows down unwanted reactions. That doesn’t mean tossing the bottle into the coldest freezer but picking a temperature range between 2 to 8 degrees Celsius—about what most lab refrigerators offer. At home, I’d use an old-school desiccator or a tight polyethylene jar with a silica gel pouch for backup. When humidity rises, especially in summer, that extra layer of protection keeps things predictable.

The Environmental Protection Agency and similar organizations stress separation from food, feedstuffs, reactive metals, and oxidizers. Learning from a close call, I’ve always placed ionic liquids like this far from acids, bases, or any metals that might rust. Even though spills rarely smoke or fume, they linger and stick around, making cleanups extra annoying. I’ve also seen lockers labeled only with trade names or half-worn stickers. Skipping clear identification causes confusion and sometimes mixing mistakes.

The Bigger Picture: People and Planet

The industry grew up with better chemical stewardship over time, partly pushed by regulators and partly from stories swapping around safety meetings. Nobody wants leaks of fluorinated chemicals or ionic liquids into shared sinks or waste streams. I always make a habit of keeping storage logs, sharing updates with coworkers, and pushing for shelf audits before old lots pile up. These small choices build trust and help everyone avoid headaches. Responsible storage saves money by reducing spoilage and helps clamp down on environmental headaches if something does go wrong.