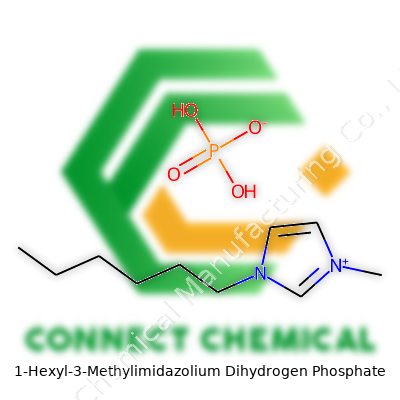

1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate: A Deep Dive

Historical Development

The search for better solvents has always shaped chemistry, and the early 2000s brought a major shift with the arrival of ionic liquids like 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate. Before ionic liquids, volatile organic compounds drove nearly every lab process, bringing fire, health, and environmental risks. Imidazolium-based salts emerged from those experiments, offering what many chemists had been waiting for: non-volatile, thermally stable, and highly customizable chemicals. The growth of this class can’t be separated from green chemistry. In my own work, swapping volatile solvents for ionic liquids cut down the headaches—both literally and figuratively. 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate benefited from this push, standing out for its balance of hydrophobic alkyl chain and anion pairing, which started carving out corners in difficult chemical applications.

Product Overview

1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate ranks among the more versatile imidazolium ionic liquids. It takes the well-understood imidazolium core—borrowed in spirit from natural compounds like histidine—and pairs a six-carbon hexyl side chain with a methyl group. The real differentiator comes from pairing it with the dihydrogen phosphate anion, nudging its chemical behavior in directions that regular halide-based ionic liquids can’t match. Chemists working on biomass processing find this combination useful: the strong hydrogen bonding from its anion can break down cellulose or lignin more effectively than many classic solvents. Looking across product data sheets, it typically appears as a colorless to pale yellow viscous liquid, easy to handle with standard equipment but needing some caution not to introduce water or strong bases that could trigger unwanted reactions.

Physical & Chemical Properties

This liquid holds onto a moderate viscosity, usually between 100 and 300 centipoise at room temperature. In real-life procedures, that means it feels thicker than water or ethanol but much easier to transfer than honey or glycerol. Its melting point sits well below zero Celsius, so it flows on the bench across typical lab conditions. The ionic nature blocks off most vapor pressure—spills don’t fill the air with odors or flammable vapors. Boiling points in the documentation rise above 350°C, but thermal decomposition happens sooner, so nobody pushes it close to that point. Water does dissolve it, and that solubility matters for waste management, mixing, and cleanup. Both the hexyl chain and the imidazolium ring resist corrosion, but over time, exposure to strong acids or bases can wear down the molecular structure. Reliable conductivity supports its use in electrochemistry, falling in the range of 1 to 10 mS/cm, influenced by purity and water content.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Manufacturers label this chemical under a CAS number, purity grade, water content, and sometimes cation/anion ratio. Commercial lots usually hit purities of 97% or better, with water below 1% for high-end applications. Color should stay clear to a faint yellow; cloudiness signals contamination or breakdown. Packaged in glass or lined polyethylene bottles, labels remind users to avoid strong oxidizers and to store tightly sealed below 30°C. Regulatory requirements include GHS-compliant hazard pictograms, though most containers do not mark it as acutely toxic—still, chemical hygiene rules apply. I always check for batch numbers and certificates of analysis, which let researchers trace material issues back to the supplier if experiments start going off track.

Preparation Method

One of the most consistent ways to make 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate starts with 1-methylimidazole and 1-chlorohexane, heated together so the chloride swaps onto the nitrogen. After careful washing to strip away unreacted reagents and byproducts, the resulting chloride salt reacts with phosphoric acid, dropping out the dihydrogen phosphate counterion through a simple acid-base reaction. This two-step sequence requires control over stoichiometry, reaction temperature, and washing. In my time working with this compound, the biggest challenges came from residual chloride, which can poison downstream reactions. Careful purification, sometimes via activated charcoal or column chromatography, helps pull up the quality. The process doesn’t need rare catalysts or extreme pressures, so most mid-scale labs can synthesize a usable batch with patience and a robust fume hood.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The core imidazolium ring stands up to most organic conditions unless hammered by strong nucleophiles or bases. The hexyl group, exposed on the nitrogen, invites reactions like halogenation or oxidation if you push it hard enough. Modifying the phosphate anion draws more attention in academic circles—swapping it for other functional phosphate derivatives shifts dissolution or catalytic abilities. Real-world applications exploit the unique blend of acidity and ionic character: in esterification, as a medium for biocatalysis, even as an electrolyte in batteries. Researchers have started grafting functional groups onto the ring or alkyl chain, extending the scope for tailored synthesis or material compatibility. Over the years, swapping the hexyl group for shorter or longer chains has tuned everything from viscosity to polarity, helping engineers pick the right variant for their process.

Synonyms & Product Names

Different suppliers list this ionic liquid under several names, causing some confusion in catalog searching. Most commonly, it appears as 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium phosphate or [HMIM][H2PO4]. Other names include Hexylmethylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate and its IUPAC equivalent. European catalogs favor systematic names, while North American vendors often lean on abbreviations. The same material might show up under trade names emphasizing its application, like “CelluloSolv PH.” This matters because research papers sometimes cite the short forms, so careful cross-referencing keeps experimental planning accurate.

Safety & Operational Standards

Working safely with 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate always starts with chemical hygiene: gloves, goggles, and splash-resistant lab coats. Local exhaust—fume hoods or ventilated enclosures—keeps skin exposures low. I noticed early on that even though this ionic liquid lacks the volatility of solvents like acetone, prolonged skin contact can irritate sensitive skin or trigger allergies in unlucky users. The dihydrogen phosphate anion brings mild acidity, so direct contact with eyes or wounds stings sharply. Waste streams must be segregated and not poured down the drain, since even low-toxicity compounds build up in the environment over repeated use. Emergency plans focus on splashes or inhalation of mist, though it’s uncommon in regular lab practice. All training circles back to responsible waste and spill management, not just keeping the experimenter safe, but avoiding harm further downstream.

Application Area

Industry has found plenty of uses that go beyond the bench-top chemistry that started it all. Pulp and paper plants use this liquid to tease apart tough plant fibers, converting stubborn agricultural leftovers into soluble sugars more efficiently than classic acid hydrolysis. In pharmaceuticals, it smooths out extraction of alkaloids or other active compounds, sometimes boosting yield thanks to the strong ionic pull. Academics gravitate to this molecule for biocatalysis: enzymes that wilt in other solvents keep running in ionic liquids, making challenging syntheses more practical. Electrochemists discovered that this compound’s conductivity serves battery research, where non-flammable electrolytes matter. My own fieldwork saw it support the separation of rare earth metals, where selectivity and environmental safety trump the old-school options. Emerging applications show up in carbon capture and even water purification; its ability to break down certain organics paves the way for new environmental tech.

Research & Development

New projects keep exploring how to fine-tune this ionic liquid’s profile for harder problems. Material scientists experiment with additives that make it compatible with plastics, opening up green alternatives to old-fashioned plasticizers or lubricants. Life sciences researchers dig into whether it denatures proteins or supports delicate biological systems; early data hints at ways to fold proteins or stabilize enzymes that don’t survive in water or organic solvents. Renewable energy labs check its stability with lithium and sodium for better batteries. Our own team has examined how trace impurities shift its catalytic properties, which feeds back into stricter manufacturing and better quality control. With each tweak, labs unravel more about how subtle changes in the molecule’s structure impact performance, sometimes in surprising or counterintuitive ways.

Toxicity Research

Initial data on 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate suggested relatively mild toxicity compared to volatile solvents, but that’s not the end of the story. Researchers report that fish and aquatic invertebrates show sensitivity to small amounts, raising red flags for large-scale release or disposal. Degradation in the environment is slow, mainly because few natural enzymes or microbes attack the imidazolium ring. In earthworms, high concentrations stunt growth and reproduction, but no acute lethality. Human data are limited, but skin irritation and allergic responses have surfaced. Chronic exposure studies in animals flag potential for bioaccumulation over months or years. As more groups publish independent data, regulators update handling and reporting guidelines. Labs switching to greener chemistry have to keep this big picture in mind; swapping one hazard for another doesn’t move the world forward.

Future Prospects

Work continues to find safer, more efficient cousins for 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate, but its current role stays secure in specialty applications. The market grows with demand for less-polluting biomass conversion, better batteries, and robust green chemical processes. Some manufacturers explore biodegradable options, breaking down more easily in soil or water. Research circles invest in toxicity mitigation, pushing for better end-of-life management and less environmental impact. Integration with automation and digital tracking in manufacturing promises higher consistency and quicker troubleshooting. The pressure now sits on both labs and industry to learn from past solvent disasters and use new options wisely—balancing performance with safety, cost, and environmental stewardship. The hope is that with smart engineering and honest toxicity studies, the promise of ionic liquids like this one can take us beyond what traditional solvents ever delivered.

Ionic Liquids and Why This One Stands Out

Ask any chemist about ionic liquids, and you’ll see their eyes light up. These salt-based fluids carry a reputation for shaking things up in labs and industrial setups. 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate belongs to this club, and its rise mostly comes from its job as a “green” substitute for old-school solvents. The fascination lies not just in its science, but in how it’s already finding its way into practical fields we count on every day.

Helping Clean Up: Green Chemistry’s New Tool

Traditional solvents create headaches. They pollute. They raise safety concerns for workers and communities. This particular ionic liquid solves a lot of problems at the source. Researchers found it doesn’t easily evaporate, reducing air pollution risks. It also beats water and many solvents for dissolving cellulose, a big deal if you’re pulping wood or looking to turn plant matter into biofuel. I’ve seen colleagues use this compound to break down tough agricultural scraps, getting closer to fuels that run cars with less environmental baggage. The same trait opens new doors in making paper and textiles with less waste.

Biocatalysis Takes a Leap Forward

Enzymes power many industries — pharmaceuticals, food, you name it. They often lose strength in regular solvents. Here, this ionic liquid gives enzymes such as lipases a stable, sometimes even improved, working space. Scientists at major pharma labs started mixing in this compound to produce certain drugs faster, with less raw material wasted. Enzyme-based reactions, which used to crawl along for hours or days, sped up and got more predictable. If you want more cost-effective ways to run chemical processes, using this ionic liquid is definitely catching on, and the data keeps getting more convincing by the year.

Electrochemistry and Energy Devices

Think of batteries or fuel cells. They need materials to move ions but stay safe, not corrode parts, and perform at different temperatures. Companies invested in next-gen batteries started testing this ionic liquid because it’s not flammable, doesn’t break down easily, and lets ions zip through fast. I spoke with a startup using it in prototype supercapacitors, aiming for safer storage in renewable energy grids. They hit fewer efficiency snags without the fire risk that comes with classic electrolytes.

Separating Metals and Recycling

Recycling old electronics or mining rare metals gets messy. Strong acids or toxic chemicals usually dominate these steps. This ionic liquid turns out to be much less harsh, giving recyclers a new way to extract metals like copper or gold from electronic waste. The difference is real: less harm to workers, and fewer toxic leftovers. Several recycling outfits started pilot projects using this stuff as the extraction liquid, and so far, they report better recovery rates and less hazardous waste piling up. It’s a game-changer for turning used electronics into valuable raw materials without the nasty side effects.

Looking Forward With Safety in Mind

There’s always a balance: industrial gain vs. environmental cost. When I talk to engineers or lab techs, safety comes up right away. 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate shows lower toxicity than many solvents, though safety checks are still ongoing. The next step includes more open data and real-world trials, so scaling up doesn’t bring new risks. Companies that jump on this should train staff and invest in waste collection for any spill or leftover ionic liquid, keeping the focus on health and environmental peace of mind.

Getting a Grip on the Risks

Chemicals used in research and industry spark curiosity and worry in equal measure. 1-Hexyl-3-methylimidazolium dihydrogen phosphate, or [HMIM][H2PO4] as it’s often called in the lab, falls into this camp. Mention of ionic liquids like this one usually perks up the ears of both chemists and safety officers. The move toward greener solvents in chemical processes feels like a smart choice, but phrases like “new material” never mean “risk-free.”

Hazards Don’t Need to Be Obvious

Let’s cut to the chase. Picture the bottle: no strong odor, a slick and slightly viscous liquid, stored under a chemical hood. The label doesn’t scream “toxic” like a jug of hydrochloric acid does. Still, anecdotal experience and published data both suggest it isn’t just water in there. Just because you can’t see the hazard doesn't mean your skin or lungs are in the clear.

Manufacturers tend to err on the side of caution with their safety data sheets, and with good reason. 1-Hexyl-3-methylimidazolium dihydrogen phosphate can cause irritation to the skin and eyes. Breathing in vapor or accidental ingestion may set off more serious effects. According to a review published in Chemosphere, some imidazolium-based ionic liquids show moderate toxicity towards aquatic life and bacteria. This sticks in the mind of anyone who’s spent afternoons wrestling with spill kits or neutralizers.

Long-Term Effects Need Watching

A lot of people push for these compounds as better alternatives to volatile organic solvents. Lower volatility brings less risk of inhaling dangerous fumes. That said, the story doesn’t end there. Repeated skin contact brings up the risk of chronic irritation. Toxicological studies on similar molecules in rats have shown potential for organ effects at high doses. Data for long-term human health impact still look sparse.

Common Sense in the Lab Pays Off

I learned early on that getting comfortable with a chemical usually leads to mistakes. Gloves and protective eyewear quickly become second nature. Standard lab practice calls for using a fume hood and avoiding direct skin contact. Even cleaning up spills demands careful steps: absorb with inert material, bag up, and dispose according to institutional rules—never down the sink.

Fact remains, some ionic liquids linger in the environment. Persistence can lead to slow buildup, affecting aquatic organisms over time. Not every lab worker thinks about where traces end up after a busy day. It matters just as much outside the workplace. Emergency crews and waste handlers rely on clear hazard communication to avoid nasty surprises. Proper labeling and accessible safety data protect both the folks in the lab and the people who clean up after.

Building Safer Habits

Improving safety starts with respect for the unknowns. Lab managers can set the standard by updating training materials with the latest research on toxicity and waste handling of ionic liquids. Connecting with chemical hygiene officers and environmental health staff leads to better awareness of proper disposal methods. The goal stays the same—for workers to return home healthy at the end of the day, and for communities to avoid long-term impacts from careless handling.

From my experience, a healthy dose of skepticism keeps people safe. No matter how modern a chemical feels, treating it with caution never goes out of style.

A Close Look at Practical Lab Safety

Everyday lab work often pushes common sense to the side. Yet, with chemicals like 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate, basic habits make all the difference. You open the bottle, weigh out a small sample, and the powder sticks stubbornly to the spatula. Just a drop of carelessness, and months of careful work face a setback, or worse, someone gets hurt. My own run-ins with similar ionic liquids taught me that safety routines grown from habit, not panic, actually keep your work moving forward.

Moisture: The Invisible Menace

This compound’s hygroscopic nature draws water from the air, turning a dry powder into a gooey mess. Once, after a hectic week, I found crystallized salt inside the screw cap—no fun to clean up, and the ruined batch failed quality tests. Uncontrolled moisture strips away product integrity and reliable results vanish. Standard facts show that most imidazolium salts break down fast after exposure to air and water. Keep containers shut tightly after every use; don’t assume a neatly capped jar in the corner will stay pure for your next experiment. Silica gel packets inside the container absorb any stray moisture—my lab mates swear by this trick for keeping stocks in good shape for months.

Temperature and Chemical Stability Go Hand in Hand

Ionic liquids look tough on paper but break down fast if left near heat sources. Labs usually reserve cool, dark storage spaces for chemicals like these. A simple setup—dedicated shelves far from ovens or direct light—serves well. There’s no fancy equipment required, but lazy placement near sunlight or radiators is enough to shorten shelf life and alter chemical behavior. Even mild temperature swings matter. My old supervisor would frown at any bottle left out during lunch break—her watchfulness saved us plenty of grief from decomposed or discolored material.

Ventilation: Basic, But Essential

One might downplay fumes with ionic liquids since these compounds don’t smell or fume like classic solvents. In reality, decomposition products can pose risks over time, building up in cramped storage areas. Good airflow—plain old mechanical exhaust or a position near external vents—keeps air clean and people safe. While handling, I keep beakers under a simple fume hood. This step became routine after a splash sent a faint whiff of acrid vapor up my nose during cleanup.

Clear Labeling: The Watchdog of the Lab

Misplaced confidence breeds mistakes. Over the years, unreadable or incomplete labels caused confusion that usually slowed down more than just one person’s work. Always write the full name, concentration, hazard class, and date on every bottle. Add storage conditions too—whether dry, cold, or away from acids. These quiet reminders on plastic tape prevent chaos when rotating chemicals or training new lab members. Studies in laboratory management link proper labeling to a steep drop in accident rates and wasted reagents.

Responsibility Extends Beyond Yourself

Storing chemicals safely rarely makes headlines, but the ripples from one careless act reach everyone in a shared workspace. I watched a colleague regroup after a container leaked on a high shelf—the cleanup took the whole afternoon, and the torn gloves told their own story. By keeping containers clean, dry, sealed, and clearly marked, you guard not only your own workflow, but that of everyone who shares your bench. A brief investment of attention each day delivers dividends in productivity, health, and, frankly, peace of mind.

Understanding Purity Beyond the Label

Take two bottles of the same chemical, both looking crystal clear on the lab bench. If one says “reagent grade” and the other says “technical grade,” what’s the real difference? Plenty. Purity describes just how much of what’s in that bottle counts as the actual chemical you need, not unwanted extras. Grades like ACS, USP, and technical tell you how tough the rules are about stray substances, such as leftover solvents or trace metals. I’ve seen cheap low-grade chemicals ruin perfectly good experiments just because the purity wasn’t high enough.

Real Impact in Research, Industry, and Health

Working in a college lab years ago, I learned the hard way what “higher purity” truly means. We used analytical grade solvents to run spectra on proteins, since even minuscule contaminants made our results fuzzy or outright useless. Early on, a supplier sent over a solvent supposedly ready for spectroscopy, but it failed every control—unexpected peaks everywhere. Our work stopped until we could source material with a grade guaranteed by a trustworthy certificate of analysis.

This doesn’t just happen in research. In manufacturing, pharmaceutical synthesis, and electronics, the tiniest impurity throws a wrench in the process. Trace iron in a chemical might corrupt an entire batch of medicine, lead to faulty chips, or trigger unplanned reactions. In one case, a contaminated reagent led to costly recalls at a plant I visited, setting production back by weeks.

The Real Risk of Poor Purity

Relying on chemicals that don’t match the needed grade can mean unfinished reactions, low yields, damaged equipment, or even health hazards, especially in medical or food-related fields. I recall hospitals having to discard essential fluids after routine tests found contamination that exceeded what’s allowed for patient use. Here, the difference between USP grade and food grade turned critical—one gets clinically tested, the other doesn’t.

On the industrial side, switching to “just good enough” technical grade solvents can look economical at first. But hidden impurities wear out machinery, cause process upsets, or demand extra cleanup costs. I’ve seen maintenance budgets balloon because a cheaper solvent left behind residues that built up in reactors and pipes.

What Builds Trust: Documentation and Reliable Sources

Choosing the right chemical really comes down to trusting the supplier’s documentation. Certificates of analysis remain a gold standard: they list specific contaminants, test methods, and actual results for that lot. It’s impossible to tell quality based on appearance alone—a clear liquid may still hide metals, particulates, or other chemicals that make a big difference in sensitive applications.

I stick to well-established distributors and look for lab reports done using validated methods. Open and regular third-party testing builds confidence that what’s on the label matches what goes into the projects. Reputable companies make safety data and test results easy to review. I’d rather pay extra upfront than risk an entire project or someone’s health.

Raising Standards in Practice

Tightening customs on quality starts by training teams to ask for the right paperwork and spot red flags in sourcing. Many labs and factories run short confirmatory checks on each new lot. Suppliers who provide quick answers and clear purity profiles keep those customers. Talking to suppliers, checking batch numbers, and requesting extra data helps catch mistakes early—long before those chemicals ever reach the end product.

In my experience, rigorous handling from ordering to storage makes a strong difference. Labeled shelves, temperature logs, and clean storage areas protect the chemical’s grade as much as the documentation. Investing in these small steps beats scrambling to fix problems caused by hidden impurities.

The Real Deal with Ionic Liquids

Ask any chemist digging into green chemistry or alternative solvents about options that promise low vapor pressure and exciting solvating abilities, and the ionic liquids crowd always shows up. 1-Hexyl-3-methylimidazolium dihydrogen phosphate—let’s use its shorter name, [HMIM][H2PO4]—often gets mentioned. This compound manages to interest both environmental scientists and industrial chemists by offering a sort of “best of both worlds” structure: big organic chunks for versatility, a phosphate group for tuning reactions.

Solubility: Where Does It Actually Go?

A huge issue comes down to a simple question: Where does this stuff dissolve?

Looking at its structure, [HMIM][H2PO4] straddles the line. The imidazolium ring and hexyl chain grant it organic character. Yet that phosphate anion carries a big charge, drawing in water. What actually happens—speaking from experience messing around in a lab with various ionic liquids—is that this one lands mostly with the water lovers. It dissolves quite well in water. That makes sense, because the phosphate group likes to grab hold of water molecules, leading to solid mixing and, fundamentally, making solutions stay clear and stable.

The imidazolium-based liquids come in all flavors, but those with big, nonpolar anions show a lot of love for organic solvents. [HMIM][H2PO4] doesn’t fall into that camp. The phosphate part makes it too polar, largely shutting it out from most organic solvents. Try adding it to hexane or ether, and it just sits at the bottom, refusing to blend in. Ethanol and methanol mix things up a bit, since they’re polar enough to occasionally help dissolve some of these kinds of salts, but even then, solubility drops off compared with plain water.

Why Should We Care?

The workplace implications hit me hardest running experiments aimed at greener extractions for metals and rare earths—something a lot of newer research keeps targeting. Water solubility becomes a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it means folks can put [HMIM][H2PO4] to use in aqueous catalysis or as neat, recycled extraction agents without heavy reliance on hydrocarbons. No toxic fumes, less trouble with containment. On the other, poor solubility in organic solvents means researchers can’t use it universally the way some other ionic liquids work across both water and oil phases. You’ve got to match the liquid to the job—if you need to pull something out of an organic matrix, look elsewhere.

Staying Informed and Safe

Journal articles, especially reviews in “Green Chemistry” or “Journal of Molecular Liquids,” pack loads of solubility data and practical tables for these kinds of salts. New data trickle out every year, but practical experience tells the main story: [HMIM][H2PO4] plays best with water. Researchers using it should keep in mind downstream waste handling. Even low-toxicity ionic liquids, once washed down drains, may disrupt aquatic systems. Labs and factories ought to monitor not just workplace exposure, but also end-of-line effluent. Investing in better filtration and recycling setups pays off because these liquids aren’t cheap, and ecological effects matter in the long run.

Better Chemistry Depends on Smart Choices

If the job at hand demands a water-loving solvent with a novel approach, [HMIM][H2PO4] gets the nod. For work in less polar, classic organic solvents, other ionic liquids fit better. Progress comes down to using the right tool for the right task, double-checking data, and keeping one eye on both lab success and long-term safety for people and ecosystems.