Exploring 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hydrogensulfate: A Closer Look

Historical Development

Chemists in the late twentieth century set out to tackle the growing environmental and performance issues tied to traditional organic solvents. Driven by a need to create safer, more sustainable alternatives, researchers in the 1990s introduced ionic liquids, unlocking a new branch of green chemistry. Among the earliest and most versatile ionic liquids discovered, 1-Hexyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogensulfate quickly stood out. Its development mirrored the push towards optimizing both process efficiency and environmental responsibility in chemical manufacturing. Practical experimentation showed that ionic liquids based on imidazolium cations, including this compound, do not evaporate into the air and reduce the risks that come with volatility and flammability, drawing the attention of professionals in synthesis and industrial process design.

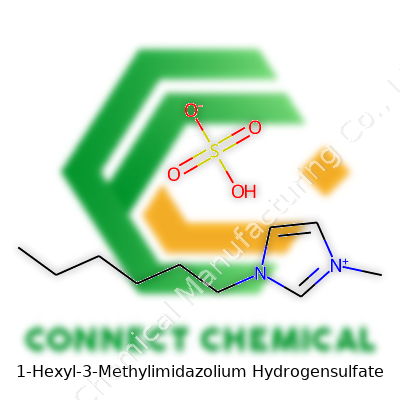

Product Overview

1-Hexyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogensulfate sits in a class of task-specific ionic liquids, formed by pairing the 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium cation with the hydrogensulfate anion. This careful pairing doesn’t just offer chemical curiosity, but presents hands-on advantages for people working in extraction, catalysis, and materials chemistry. Its unique ionic nature sets it apart from classic solvents, opening the doorway to specialized chemical environments where standard solvents pose limitations or hazards. Handling and storage have changed how labs and factories approach recycling and reusability, since this substance rarely suffers degradation through ordinary use.

Physical & Chemical Properties

With a pale yellow, viscous appearance, 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogensulfate pushes past boundaries of what most solvents could manage. It remains stable at room temperature, avoids catching fire, and rarely evaporates in open air. Its density falls close to 1.1 g/cm³, stacking up as more dense than many organic solutions, and its melting point often stays below standard laboratory temperatures. Dissolving salts, nonpolar organics, and some metals becomes more straightforward, as this ionic liquid provides a middle ground few others reach. The highly polar environment inside its structure lets researchers target reactions that choke in water or traditional organic solvents.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Market samples normally come with purity upwards of 98%. Usually, labeling on drums or ampoules features the structural formula, batch number, and essential hazard pictograms tied to the hydrogensulfate anion’s corrosive properties. Industry regulations set expectations for water content, color, and acid-base titers, since trace amounts alter its solvent abilities or accelerate side reactions. My work in synthesis has always demanded reliable supply data, so proper lot certification and reporting of storage conditions remain at the forefront. Transportation involves following chemical safety standards, with plain, durable containers and clear hazard identification visible at a glance.

Preparation Method

Manufacturing this ionic liquid draws from accessible, inexpensive starting points—1-methylimidazole and 1-chlorohexane—to begin alkylating the imidazole core. The subsequent metathesis with sodium hydrogensulfate, carried out in anhydrous environments and monitored with simple titration or NMR, leads straight to the target salt. Washing and drying the product rids it of impurities, sometimes with extra filtration steps to achieve the needed purity. From a practical viewpoint, balancing reaction temperatures and mixing speeds avoids excessive degradation or darkening, which spells trouble for downstream use in catalysis or extraction. Plant-scale production focuses on reproducibility and minimizing waste streams, reflecting the solvent’s early promise of greener chemistry.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The core structure—an imidazolium cation with a flexible aliphatic chain—welcomes modifications in both scope and scale. Swapping the hydrogensulfate for other anions calibrates the acidity, while tweaking the alkyl groups on the cation offers fine-tuned solubility or thermal properties. As a solvent, it hosts acid-catalyzed esterification, cellulose dissolution, and metal separation protocols that struggle in other media. Its moderate acidity gives a selective edge in activating electrophiles while holding back unwanted side reactions. Specialists working in biomass processing, for instance, highlight its ability to tackle lignin and recalcitrant plant materials by opening up tight hydrogen bonds, something hard to reproduce with classic acids or alkalis.

Synonyms & Product Names

Chemical catalogs and research reports rarely pick just one name. You’ll see 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogensulfate, sometimes shortened as [HMIM][HSO4], 1-methyl-3-hexylimidazolium hydrogen sulfate, or even as the corresponding CAS number 410522-11-7. No matter the brand or label, the core structure and properties stick around, ensuring users get what they expect across vendors from Sigma Aldrich to niche manufacturers. Frequent crosschecking among product names helps avoid mix-ups, especially when working with suppliers where English may not be the first language.

Safety & Operational Standards

Anyone running a synthesis or handling process with this compound learns to respect its mildly corrosive hydrogensulfate nature. Even though the ionic liquid format clips the flammable risk common to solvents like benzene or acetone, skin, eye, and inhalation exposure still require personal protective equipment—gloves, goggles, and ventilation as necessary. Plant operators build standard operating procedures around closed systems to curb accidental spills, since cleanup brings both environmental impact and personal hazard concerns. Disposal routes typically involve neutralization with basic media before release, and all involved need routine training on chemical hygiene to keep up industry trust.

Application Area

You’ll run into this compound everywhere innovative chemists need high performance with an eye on sustainability. In extraction processes, it pulls rare earth elements, noble metals, and specialty organics from complicated mixtures, cutting out toxic solvents. Catalysis teams use it to stabilize acid-sensitive intermediates across pharmaceutical syntheses and biofuel development. In polymer science, it softens stubborn biopolymers or supports precision molding that cranky old solvents can’t match. Battery and electrochemistry groups appreciate its impressive ionic conductivity, helping build safer electrolytes in the pursuit of longer-lasting storage.

Research & Development

Universities and chemical companies treat this ionic liquid as a platform for finding economies of scale and eco-friendly options. Research keeps digging into task-specific versions with new cations, anions, or functional side chains. Teams measure how it tackles major technical challenges—better solubility for cellulose, selective extractions for recycling metals, novel modifiers for carbon nanotubes. My own experience in academic research pointed to the wide-angle versatility, watching graduate students compare reaction rates and separation yields in side-by-side tests that show clear advantages. Funding cycles reward proposals that blend this liquid's performance with low-waste goals, reflecting broader green chemistry trends.

Toxicity Research

Studies track the impact of imidazolium-based liquids on soil and aquatic life, with outcomes depending heavily on both dose and breakdown paths. Earlier assumptions of low toxicity sparked optimism, but thorough screening tells a more cautious story. Chronic exposure causes issues for small organisms, though proper containment and responsible disposal how the field avoids repeating pollution mistakes of classic solvents. Researchers keep the pressure on for improved safety monitoring and clear labeling, since scaling up without forethought risks both human health and ecosystem balance.

Future Prospects

The next generation of ionic liquids could stem from what we learn now about 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogensulfate. Demand for alternatives to traditional solvents grows alongside digital manufacturing, battery innovation, and pharmaceutical scaling. Advances in recycling pathways, biodegradability, and toxicity control will shape how this compound remains not just a specialty chemical but a core tool in future lab and plant work. As policy makers and industry leaders hunt for answers to greener chemistry, this story highlights the importance of cross-discipline research and a willingness to rethink old habits. Trust between producers, users, and regulators grows stronger where transparency and ongoing data back up every drum, ampoule, and process update. By keeping communication open and safety at the core, the benefits of this chemistry spread through every downstream product and discovery.

Peeking Into a Modern Chemical Tool

If you poke around in any chemistry lab hunting for something a bit unusual that still manages to punch above its weight, you’ll probably find someone working with ionic liquids. Long names, odd smells, and labels with more syllables than you care to count. There’s one that keeps coming up in academic conversations: 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hydrogensulfate.

People often ask what this tongue-twister actually does, why so many researchers and engineers keep a vial of it handy, and why it pops up in journals from Europe to the other side of the world. It’s not just some esoteric curiosity. It brings real value in a handful of places that touch our daily lives—even if those links aren't obvious from the name alone.

Breaking Down the Benefits

First, it’s all about what makes it different from regular liquids. Water and most solvents have one thing in common: volatility. Spill a bit on the bench, it’s probably gone in an hour. This ionic liquid doesn’t play by those rules. It sits there, not interested in evaporating, and it shows almost no vapor pressure. That rare quality opens the door to safer, less polluting lab work.

I remember the first time I saw it in action during a green chemistry demo. We'd used it to extract heavy metal ions from a wastewater sample. Other solvents would have turned the lab into a stinking mess, but the ionic liquid kept everything contained. This property makes it a favorite among environmental tech startups. It handles metal separation with a surgical touch—removing lead, mercury, or cadmium—and then separates out when you want to recover your sample or purify water.

Catalysis might sound like a sleepy concept, but in industrial chemistry, you want reactions to go fast and stay clean. This compound steps in as a solvent and sometimes as a catalyst itself. During organic synthesis, for instance making esters or purifying pharmaceuticals, it speeds things up, flattens waste byproducts, and can be recycled for multiple runs. I’ve seen grad students light up when their stubborn projects finally come together thanks to this liquid’s quirks.

From the Lab to the Factory Floor

Plenty of industries aren’t satisfied with chemicals that perform well only at a bench scale. They want something that lasts on the factory floor. This ionic liquid’s stability earns it a nod from folks in battery and electroplating sectors. I once sat in on a battery tech symposium where a team brought up swapping out conventional, fire-prone electrolytes for this liquid, cutting down on explosions and fires—hard to argue with better safety.

People worried about green tech often talk about closing the loop. Here, the ionic liquid helps in recycling processes. Plastic waste, especially PET bottles, can get broken down with its help—turning garbage into useful feedstocks for new manufacturing. Progress here could mean less landfill, less reliance on crude oil, maybe even cheaper recycled goods at the corner store.

Stepping Into the Future

No chemical is perfect. Price, scaling issues, and disposal challenges still hang around, but 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hydrogensulfate keeps making inroads as researchers tweak recipes and processes. The more it gets recycled, the greener and more cost-effective it looks. Public investment in sustainable chemistry, rigorous safety studies, and smarter waste policy would help it—and a bunch of related compounds—play a bigger role in making chemistry safer for workers and the planet.

The Chemical in the Lab

Over the past few years, ionic liquids like 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hydrogensulfate have become popular in both academic and industrial labs. Their popularity comes from their unique properties—non-volatility, low flammability, and the ability to dissolve many substances. I've seen chemists excited over their green chemistry potential, especially since they don’t smoke up the lab with fumes like older solvents do. This chemical offers some advantages but safety is far from automatic.

Touch, Breathe, or Spill—What Happens?

One mistake often made is assuming these clear, oily liquids are harmless just because they aren’t highly flammable. Direct contact can cause burns or strong skin irritation. Splash some on your gloves or coat and you’ll feel an itch or burning sensation after a while. Inhaling the vapors over a long shift, even in modest concentrations, can lead to headaches and throat irritation. Respiratory issues have cropped up in my own circle after colleagues rushed through filtration steps without proper hoods.

Reviewing the Data

Material safety data sheets from chemical suppliers show 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hydrogensulfate rates as harmful if swallowed or handled without care. Animal studies pointed out liver and kidney damage after repeated exposure. Environmental researchers highlight its ability to disrupt aquatic life when released from labs as waste. The European Chemicals Agency calls for tight control of emission during use and disposal.

Real-World Safety Practices

Every time I’ve worked with this compound, the usual drill involves wearing nitrile gloves, chemical splash goggles, a lab coat, and working inside a fume hood. If the material escapes containment, it’s easier to wipe up with absorbent pads designed for corrosive material, never just with paper towels or rags. I’ve learned to double-check gloves for pinpricks before starting on any step, since even a tiny hole can spell trouble after a few splashes.

Disposal practices make a difference, too. Dumping this substance in the sink poses risks not only to lab staff but also to local water systems. The right process sends all ionic liquid waste into departmental hazardous waste bins, then out via certified disposal companies. I’ve noticed many junior staff are tempted to skip this and throw it out as general lab waste. Direct reminders from supervisors—and practical demos—do more than posted signs for keeping safety top-of-mind.

Building Safer Lab Habits

It helps to treat every handling session as a chance to refresh basic habits. Training new lab members on respect for ionic liquids, using clear real-world stories, brings more buy-in than abstract warnings. Refreshers every few months—using new findings and incident reviews—keep everyone focused on prevention. Labs that set up easy-to-follow checklists, next to fume hoods and sinks, end up with far fewer accidents.

Respect the chemical and invest in regular safety steps. This approach cuts down emergency room visits and damage to both people and the environment. Over time, building a culture where safe habits feel automatic pays off more than any single technical fix.

Handling a Modern Ionic Liquid

1-Hexyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogensulfate turned the heads of chemists for its green chemistry profile and flexibility in labs and industry. The promise is big, but care in how to store it spells the difference between reliable results and wasted batches. Talking from experience, people underestimate liquid stability often. They see an ionic liquid on the shelf and get relaxed. Then the bottle degrades, the cap crusts up, and suddenly a project stalls for days. That slow shift in color or viscosity means someone got storage wrong.

Temperature Makes a Difference

Keep this ionic liquid around 15–25°C for best stability. Heat breaks it down, cold may cause it to separate or crystallize. I remember once a bottle sat near a steam radiator for a week. We opened it to find a sharp smell and darkened liquid—the degradation set our timeline back. It only takes a few days in the wrong spot to lose a good bottle. Ordinary fridges work if the space stays dry, but most shelves in labs fit the bill. Don’t shove it near direct sun or next to a hot plate. Quality drops off quickly above 30°C.

Choose the Right Container

Air exposure causes trouble. Sulfate ions like to soak up water from the air, and the imidazolium ring doesn’t love oxygen for the long haul. A glass bottle with a Teflon-lined cap or sealed HDPE works best. Skip low-grade plastic; I learned this after a supplier delivered a plastic jug. The liquid softened the walls over months, ending with a sticky mess and an expensive cleanup. Even with a good bottle, make sure it seals tight, and don’t let vapor linger around headspace. Use foil seals if storing for weeks on end.

Keep Water and Dust Out

Water changes its properties fast. Lab humidity saturates it given the chance. If you open and close the bottle more than once a day, open it under dry air or nitrogen. In some synthesis work, just a drop of water ruins reaction selectivity. This reminds me of a time someone left a bottle open on the balance. An hour later, it weighed a little more and our NMRs ended up a mess, full of water peaks. Even taping the bottle cap in a humid room keeps things better. Dust can introduce other ions, skewing results, so stick to using clean spatulas and fresh gloves each time you measure it out.

Keep Clear Labels and Remember to Rotate Stock

Label every bottle the moment you crack the seal. Date, initials, and any strange incidents—such as spills or prolonged exposure—go on the label. It’s boring, but tracking who opened a bottle last week makes it easy to trace issues. Rotate the old stock to the front. I’ve seen people reach for the farthest bottle in the fridge only to discover it expired two years ago. Simple habits avoid big headaches.

Build Consistency and Safety

While 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogensulfate doesn’t act as explosive or highly flammable, treat it with respect. Avoid storing next to oxidizing agents or acids. A safe supply cabinet with limited access wins over a cluttered shelf every time. Fume hoods help if there’s a risk of vapor buildup, but that’s rare outside unusual thermal conditions.

All these habits boil down to keeping this compound as stable as when it left the supplier. Fail on dryness, temperature, or container choice, and you risk project setbacks, lost money, and wrong data. Experience in the lab teaches that cutting corners with storage transforms even the greenest chemistry into a gamble.

Understanding the Risks

Anyone who has handled 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium hydrogensulfate knows this isn't some harmless kitchen cleaner. We're talking about an ionic liquid that's found a place in labs and industry for advanced chemistry, extraction, and catalysis. It's powerful, but with that comes an obligation—both legal and moral—to respect its potential to harm humans and the environment. Studies point out this substance can cause skin irritation, lung issues, and water toxicity. Dumping it down a drain or tossing it out with regular trash can send it right into our drinking water or the wider environment.

Regulations Aren’t Optional

In my experience, local laws could not be more clear: hazardous chemical disposal belongs in the hands of professionals. The EPA and state regulators take a dim view of anyone skirting hazardous waste rules—just ask anyone who’s paid an environmental fine. Universities and companies that keep things above board all have dedicated chemical waste storage, labeling, and removal. Staff have to follow specific Standard Operating Procedures. The record-keeping keeps everyone honest, and the risk of someone getting careless drops dramatically. No shortcuts, no excuses.

What Actually Works

In practice, waste solutions containing 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium hydrogensulfate get funneled into labeled containers—never mixed with other chemicals unless the SDS confirms compatibility. The waste contractor picks them up and handles it all in a treatment or incineration facility that can break down complex organics into harmless byproducts. Often these places use high-temperature incinerators that destroy the molecule entirely, leaving only CO2, water, and trace simple salts. Anything less poses a danger to the people nearby and those downstream.

Why Training and Culture Matter

From running student labs, I've seen how habits from the top shape what happens day-to-day. Good training sticks. If lab workers treat every waste bottle like it could bite, spills drop, injuries fall, and mystery bottles on the back shelf become rare. Visitors from businesses with tight safety cultures tell me some employees refuse to touch chemicals unless they can trace every drop’s final destination. That discipline matters, especially with persistent compounds like these ionic liquids, which don’t break down quickly in rivers or soil.

Real Solutions—Not Just Rules

Beyond policies and incinerators, real progress comes from designing lab processes with less risky materials. Green chemistry aims to replace compounds like 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium hydrogensulfate where possible. Synthetic pathways that avoid hazardous byproducts protect workers and lighten the load on waste handlers. Substitution always beats remediation. Vendors also play a part—every responsible supplier should provide not only a full Safety Data Sheet, but real disposal guidance tailored to typical user scale.

Take Responsibility at Every Step

The most important lesson from years in the trenches: chemical disposal isn't just paperwork and bins—it’s stewardship. The cost of getting it wrong lands on communities, not just the person holding the bottle. Suffering from contaminated water or a chemical burn hurts more than any inconvenience spent calling the hazardous waste contractor. By owning every step, from labeling waste to final treatment, we solve problems before someone else has to clean up after us.

Understanding the Basics

Chemists spot the name 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogensulfate often in academic papers and technical sheets. This ionic liquid has quite a buzz in research and industry, particularly because of its ability to dissolve a wide range of substances. When a compound plays a leading role in separation processes, catalysis, or electrochemistry, everyone wants to be sure about what exactly sits in their flask.

Purity Isn’t Just a Number

Most suppliers list this ionic liquid’s purity level at 98% or higher. That seems high, and it is, but anyone who's pipetted a clear liquid from a fresh bottle knows small impurities make a big difference in lab results. Purity isn’t just about pride—it’s about performance. In reactions involving ionic liquids, stray water, halides, residual solvents, or trace metals can throw off yields or even corrode expensive gear.

A friend of mine discovered the hard way that a 95% batch still carried just enough leftover halide to compromise a catalytic system. That setback cost days of troubleshooting and a new order. Labs working with ionic liquids often insist on certificates of analysis that chart out moisture content (commonly below 0.5%), halide levels (usually less than 100 ppm), and the absence of volatile organics. These specifics don’t just fill paperwork; they form the foundation for reproducibility and safety.

Why Specifications Matter in Real Work

Handling 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogensulfate, most chemists expect it as a viscous, colorless to pale yellow liquid at room temperature. The melting point usually falls well below room temperature, which matches its use as a solvent or in electrolyte mixtures. For those who’ve worked with low-melting-point ionic liquids, that familiar syrupy feel flags quality.

Density numbers usually land between 1.1 and 1.3 g/cm³. Water content, measured by methods such as Karl Fischer titration, tells whether proper storage or drying took place. An over-dried sample may not cause much trouble, but extra water can reduce physical property control or activate unwanted side reactions. Again, it always pays to ask for a batch analysis.

Trusting the Supply Chain

Suppliers sometimes cut corners or skip robust purification to price their stock lower. Those hunting for reliability partner with producers who list trace-level data, support stable analytical procedures, and offer technical support. Preferring a sample scale-up over a bulk purchase may sound like common sense, but it saves costs and headaches.

For applications in green chemistry or high-end electronics, finer controls appear in the specs, such as elemental analysis and NMR data. Any drift from declared purity, such as extra color or a suspicious smell, signals that you need to run quick in-house tests before using a new lot.

Pushing for Better Transparency

Research teams and factories gain by setting clear acceptance criteria. This avoids disputes over interpretation and minimizes downtime from bad batches. Open communication with suppliers and requiring transparent reporting have cut wasted time in my experience. When you treat specs as non-negotiable, you don’t just buy a chemical—you invest in results.