Commentary on 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate: Progress, Properties, and Perspectives

Historical Development

Back in the late 20th century, researchers began to dig into the properties of ionic liquids, searching for alternatives to volatile organic compounds in all kinds of chemical processes. The synthesis of 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate (also recognized as HMIM TFA) marks a turning point among these efforts. Its development rests on the foundation built by earlier imidazolium salts, yet the tweak of combining a hexyl tail with a methyl group and a trifluoroacetate anion opened new doors for customizing solvent behavior. The push for greener, safer solvents really drove attention to these materials, especially once the performance and adaptability of HMIM TFA became clear in the lab and in pilot scale processes.

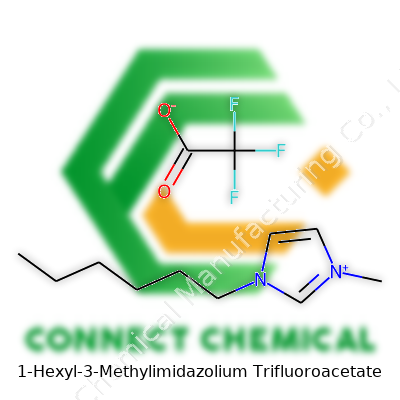

Product Overview

1-Hexyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate usually shows up as a clear to pale yellow viscous liquid at room temperature. The structure — a positively charged imidazolium ring attached to a hexyl and a methyl group, paired up with a trifluoroacetate anion — tucks important features into a single molecule. This setup changes how it interacts with water, organic solvents, and a variety of solutes. Demand from chemical manufacturers, researchers, and specialty product developers spurred the commercial availability of HMIM TFA, each batch aiming for high purity and minimal contaminant traces for consistent results.

Physical & Chemical Properties

By examining 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate, it’s clear how molecular engineering makes a difference. This ionic liquid refuses to evaporate under standard lab conditions, keeps stable through a big temperature window (often cited between -20°C and 200°C), and holds thermal stability that rivals traditional organic solvents. One thing I’ve noticed working with these types of liquids: the viscosity stands out — not always water-thin, sometimes edging closer to honey at lower temperatures. The trifluoroacetate anion gives strong hydrogen bonding and alters polarity, making HMIM TFA mix well with many organics while drawing in enough water to change its properties. The liquid doesn’t burn or fume easily, which proves critical for safe handling. These liquids resist wide swings in pH, stay stable when exposed to a lot of common chemicals, and don’t degrade just from contact with air or light over the course of everyday lab work.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Weights, concentrations, and purity levels matter to both bench chemists and production engineers. HMIM TFA comes in typical lab bottles or bigger industrial drums, each labeled to show molarity, precise formula (C12H19F3N2O2), batch number, and recommended storage conditions. Purity checks help spot halide impurities, water content, and residual solvents, all crucial for reaction planning. If you look at technical datasheets, you’ll see clear details covering density (usually floating around 1.1-1.2 g/cm³), melting and boiling points, as well as hazard codes and suggested personal protection. This saves time and avoids confusion, especially in fast-paced projects.

Preparation Method

Lab technicians and chemical engineers often start with 1-methylimidazole and 1-chlorohexane to form 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride by a straightforward alkylation. Afterward, they handle anion exchange using sodium trifluoroacetate, separating out sodium chloride and pulling HMIM TFA into an organic phase. Washing, drying over molecular sieves, and filtration polish up the result. It’s a hands-on process that takes patience because of the need to scrub out inorganic residues and guarantee complete removal of unreacted starting materials. Scale-up for commercial purposes repeats these steps with tweaks for bigger volumes, but the basic method sticks.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

As a backbone, HMIM TFA plays well in organic synthesis. It works as a solvent or catalyst in alkylations, cross-coupling, and even biocatalytic reactions. The molecule sometimes hosts further tailoring — swapping out the anion changes solubility and thermal range, and tuning the alkyl chain on the imidazolium ring customizes viscosity and polarity. I’ve watched researchers swap out trifluoroacetate for other carboxylates or even mix HMIM TFA with other ionic liquids to sharpen separation abilities in difficult analytical processes. It rarely takes on direct chemical reactions, instead serving as an environment or medium that brings out better selectivity in what’s going on inside the flask.

Synonyms & Product Names

This chemical wears a few names: 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate, HMIM TFA, or simply the longer IUPAC name for those deep into nomenclature. Catalogs sometimes list it as [HMIM][TFA] or under original trade names depending on supplier branding, which helps clarify which salt or formulation lands on the shelf. This avoids confusion when ordering for research or production runs.

Safety & Operational Standards

One frequent concern with workplace handling focuses on minimizing inhalation and skin contact. Safety data sheets point out low volatility but nudge workers to use lab coats, goggles, and gloves — not because HMIM TFA behaves aggressively, but to stay safe with repeated use and avoid chronic exposure. Spills call for cleanup using nonflammable absorbents. Local regulations guide disposal, never just dumping down the drain. Labs and plants keep it in cool, dry, vented places, often with records of access to comply with internal chemical management policies. Keeping up with safety training reduces risk.

Application Area

The biggest splash for HMIM TFA shows up in green chemistry and solvent applications. Chemists turn to it during catalyst recycling, organic synthesis, and sometimes in cleaning solvents that need low toxicity and minimal vapor release. Analytical labs appreciate its role in extractions, speeding up separation processes that usually take longer with classic solvents. Pharmaceutical development sometimes leans on ionic liquids for their low residue and unique solvation ability, and HMIM TFA sits among those options. Some programs also investigate it for processing biomass and dissolving cellulose, hinting at a future in renewable materials. The move away from hazardous, flammable organics keeps driving attention in both research and production lines.

Research & Development

Academic teams and industrial labs keep pushing boundaries, measuring properties and inventing new uses. New data arrives from studies on hydrogen bonding, dynamic viscosity under pressure, and electrochemical stability. Customizing the anion expands possibilities, while blending HMIM TFA with other ionic liquids sharpens selectivity for challenging separations. Researchers publish on how well it performs in removing sulfur from fuels or catalyzing key organometallic steps. The technology continues to evolve as better analytic tools and big data techniques dig deeper into why HMIM TFA outperforms older solvents in certain jobs.

Toxicity Research

Toxicity checks matter as demand increases. Acute exposure studies generally show low oral and dermal toxicity in animal models, but understanding full long-term risks takes deeper investigation. Some reports raise questions about slow biodegradation, so environmental chemists investigate breakdown products and their effects on aquatic life. Keeping HMIM TFA out of natural water systems still dominates safe practice policy. Regulatory agencies in the EU, US, and Asia keep a close eye on any evidence for mutagenicity, carcinogenicity, or reproductive effects, striving to keep standards updated with new data.

Future Prospects

Big improvements look set to arrive as researchers get better at designing tailored ionic liquids. As companies press towards electrification, battery production, and more sustainable industrial processes, demand keeps climbing for safe, stable, and flexible solvents. HMIM TFA’s role is likely to expand, especially wherever performance, reduced emissions, and safety overlap. Next-generation materials, cleaner synthesis approaches, and advanced separation technology all stand to gain from further understanding and optimizing this compound’s features. Continued investment in toxicity, environmental fate, and large-scale production will shore up confidence for wider adoption, both in specialty markets and in mainstream industry. The shift to greener chemical production will not slow down, and products like 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate sit right in the crosshairs of that momentum.

Why Scientists Value This Unusual Salt

Researchers talk a lot about ionic liquids. My first real brush with them came during a climate change research project in college. Back then, picking a solvent that didn’t boil off or catch fire quickly gave us hope for safer labs. 1-Hexyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate is one of those salts that stays liquid at room temperature, which always felt odd after years of pouring powders out of jars in high school chemistry.

Dissolving Plant Material: A Tough Nut

Breaking down wood hasn’t ever been easy. Standard acids chew through plant fibers, but they can ruin the molecules you want. That’s where this compound really shines, especially in research about renewable energy or green chemistry. This ionic liquid stands out for its knack for dissolving cellulose and lignin straight from wood chips or agricultural waste. That’s a big deal since it opens a new path for scientists trying to turn stubborn plant waste into biofuels, textiles, and specialty chemicals.

There’s a set of reasons why this salt works so well here. The imidazolium part of the molecule teams up with the trifluoroacetate group, finding just the right balance between ripping through strong plant bonds and still keeping things stable. I remember visiting a pulp mill during an internship and smelling that harsh, sulfury air. This solvent offers an alternative, one that skips volatile fumes and cuts down on hazardous byproducts.

Supporting Greener Industry

Early on, I believed green chemistry sounded like wishful thinking. After seeing these ionic liquids pull off what strong bases couldn’t, my doubts started to slip away. Labs now use 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate not just for biomass breakdown, but also for extracting valuable compounds from all sorts of natural feedstocks. Pharmaceutical and food scientists have picked it up for isolating enzymes or proteins from messy biomass, avoiding rougher solvents.

The ability to recover and reuse this compound means less chemical waste. Unlike old-school methods that dump buckets of acids after every run, ionic liquids can get cleaned up and cycled back in. That matters in the race toward lower emissions and better resource management.

Challenges Don’t Go Away

Wider use of ionic liquids in industry still runs into a few stubborn roadblocks. Price tags for large-scale production remain high, and disposing of these liquids safely once they’ve picked up impurities keeps lab managers up at night. The trifluoroacetate part, though great for breaking down plant fiber, requires careful handling to prevent environmental contamination.

Scientists have started to work with regulators and manufacturers to sort out disposal, hoping to strike a balance between powerful chemistry and safety for both people and ecosystems. Pushing research forward also includes finding new ways to recycle or redesign the molecule for faster cleanup.

Looking Ahead

As green tech gets bigger, expect more headlines about ionic liquids like this one. Breaking the stubborn links in cellulose can put more bio-based products on store shelves, and safer methods for dissolving waste makes the case for scaling up. I’ve seen skeptics turn into believers after seeing these liquids pull tough jobs, and that kind of change doesn’t come around often in the chemical world. Keeping a close eye on safety, costs, and long-term impact will determine how widely these lab favorites turn into real industrial tools.

Understanding the Risks of This Ionic Liquid

1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate is one of the ionic liquids that gets a lot of attention in chemical research and industrial applications. Through years of working in academic and industry labs, I've seen how new chemicals often get labeled as "green" or "safe" just because they don’t evaporate like traditional solvents. But these assumptions can lead to serious problems. We can’t judge safety just by volatility or flashpoints.

Health Concerns: What Everyone Deserves to Know

This compound isn’t the worst thing you’ll find in a laboratory, but calling it risk-free ignores some basic facts. Studies have shown imidazolium salts can irritate skin and eyes, and some reports link longer exposure to cellular toxicity in lab animals. Organic trifluoroacetate anions carry their own concerns, since many fluorinated chemicals last a long time in the environment and can build up in the body if not handled carefully. Data points to moderate toxicity if inhaled, ingested, or absorbed through skin, which matches what technicians and chemists see in daily work: skin dryness, throat discomfort, eye redness.

Personal experience tells me that safety data sheets only give part of the story. Some liquids don’t give off strong odors or fumes, leading people to underestimate the hazards. Months ago, a colleague accidentally spilled a few milliliters on his arm. He washed it off, thinking the liquid looked harmless, but he still ended up with a nasty rash and tingling fingers for two days. That’s the real world in action—not just academic toxicity values.

Protective Steps That Work

The best habits in labs and production facilities start with basic precautions. Gloves, goggles, and full-length sleeves or lab coats block skin exposure, which prevents those rashes or chemical burns people regret later. Good ventilation and working in a fume hood take fumes and droplets off the table, lowering the odds of breathing in something invisible and irritating. Whenever we moved to new chemicals, the first thing our team did was test glove compatibility and check spill procedures. Splash-proof containers and labeling give another layer of protection, especially if a room sees a lot of different projects running in parallel.

Fresh eyes on protocols make a difference. Supervisors who actually watch their team’s workflow spot shortcuts and adjust safety plans before accidents become statistics. One overlooked step—such as leaving a bottle open or stacking waste containers near drains—can turn a low-risk activity into a serious setback.

Disposal and Environmental Impact

Some ionic liquids are called “designer solvents,” but that doesn’t mean the waste vanishes into thin air. Trifluoroacetate compounds don’t break down quickly in water or soil. The safest approach involves sealed hazardous waste bins and scheduled pickup by licensed handlers. I’ve seen too many labs treat these like less toxic organic solvents, only to run into expensive cleanup rules or face heavy fines for improper disposal. My best advice comes from these lessons: never pour anything down the drain unless a safety officer approved it.

Building Better Safety Habits

Nobody benefits from taking shortcuts with chemicals like this. Training makes safety automatic; regular drills and quick access to up-to-date safety information help teams stop accidents before they happen. The safest labs encourage workers to speak up about near-misses or problems, building a culture where everyone owns the risk and the fix. The newer the compound, the more important these habits become, because published data almost always lags behind real-world experience.

What matters is treating every substance—old or new—with healthy respect and staying updated on best practices. People trust experience more than labels, and the smartest teams rely on both.

A Real-World View on Solubility

Chemistry often touches daily life in ways few notice. The solubility of ionic liquids such as 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate, sometimes called [C6mim][TFA], draws both curiosity and practical interest. This compound—formed from a bulky imidazolium cation and the trifluoroacetate anion—bridges two worlds: the water-based and the organic.

Water Solubility Matters

Some assume all ionic liquids break apart in water. This one doesn’t rush to dissolve, though it does mix. Peer-reviewed journals put its water solubility at roughly 1–10 grams per 100 milliliters, depending on temperature and impurities. The trifluoroacetate anion, light and polar, helps the salt engage with water molecules. The long hexyl chain, though, brings grease to the party and resists water’s pull. This balance shapes the partial solubility seen in the lab. If you stir it, you’ll see some separation, especially if the temperature’s cool. Raise the temperature and you’ll find better mixing, which helps during chemical extractions or enzyme reactions.

Organic Solvent Compatibility

Pour 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate into nonpolar organics like hexane and there’s almost no mixing. The bulkier cation won’t win over nonpolar molecules. Try polar solvents such as methanol, acetonitrile, or dimethyl sulfoxide and the picture changes. In methanol or acetonitrile, it dissolves well because both the cation and anion form hydrogen bonds and dipole interactions with the solvent. DMSO and acetone welcome it, too. In my own work, I’ve seen clear, uniform solutions in methanol, less so in ethanol, and just a slight haze in less polar organics. Lab notes from colleagues mirror this pattern.

Why Solubility Knowledge Matters

Applications depend on these solubility quirks. A water-rich process, like some biocatalysis reactions, runs smoother with partial solubility so both enzyme and substrate see the ionic liquid. Extraction processes benefit if the compound picks a side—either water or organics—because it lets chemists separate products cleanly. Sometimes, researchers tweak the alkyl chain length to push the balance toward clearer separation or better mixing, depending on whether more or less water contact is helpful. Changing that chain by even a few carbons changes the game.

Supporting Data and the Research Trail

Studies in journals like Green Chemistry and the Journal of Physical Chemistry point out that solubility figures can vary, reporting water solubility from a few grams per 100 milliliters up to twenty grams, depending on subtle lab conditions. The longer alkyl chain trims down water solubility compared to shorter cousins like 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate, which would dissolve easier. Large numbers of published phase diagrams give practical chemists a shortcut. Turn to those if you want solvent blends for tricky separations.

Pushing Toward Solutions

For industry, the solubility limits often call for new approaches. Combining 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate with cosolvents, adjusting temperature, or adding salts can nudge the partitioning just enough for better outcomes. Testing in-house, rather than trusting textbook numbers, always pays off. Safety, disposal, and cost hinge on getting this right, not only for the lab but for scale-up. Solubility isn’t just an academic detail—it shapes entire workflows, waste streams, and downstream recovery.

Final Thoughts on Practical Use

From sample prep to clean up, solubility directs operations. Knowing where 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate feels most at home—water, methanol, or somewhere in between—guides both small experiments and large-scale processes. Account for that long hexyl tail. Watch how temperature and solvent choice tip the balance. There’s no single answer, just experience and real-world testing.

The Real Deal with Storing Ionic Liquids

1-Hexyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate isn’t a household name, but it piques the interest of anyone dealing with solvents or chemical synthesis. This liquid has been turning heads for its usefulness as a green solvent, especially in cellulose processing and protein handling. Yet its safe handling often gets shoved aside in favor of flashy lab results. I’ve learned over years of working in labs that safety with such liquids comes down to a few solid habits, not just memorizing safety data sheets.

Stability Isn’t an Excuse for Carelessness

This ionic liquid doesn’t go up in flames like some solvents, and it rarely makes headlines for volatility. Still, the trifluoroacetate anion means moisture can play havoc with purity over time. Water in the bottle can cause slow hydrolysis, leading to slow but steady chemical change. Maybe it doesn’t sound dramatic, but that slow shift compromises results and puts experiments at risk. If you want to use it for precise tasks—like dissolving tough biopolymers or tuning catalyst activity—keep it tightly sealed in an air- and moisture-free environment.

Temperature Control: Not Just for Show

I’ve seen colleagues leave ionic liquids on open benches, assuming their low vapor pressure means no harm done. The truth: even these stable liquids can go down the drain through slow decomposition or unnecessary side reactions if exposed to air and fluctuating temperature. Storage at room temperature usually works, but swings above 30°C can accelerate breakdown, especially for longer-term storage. Refrigerators do the trick better, provided the container isn’t subject to repeated condensation or frost buildup. No one gets reliable results from product contaminated by condensation, and lab repairs never go well after a spill from a split frozen bottle.

Container Choices Matter

Glass containers with tightly fitting polypropylene caps beat out any ordinary bottle. Avoid metal where possible—metal ions can catalyze decomposition or introduce color changes. Having worked with similar ionic liquids, I keep samples in amber glass bottles. Light can be a slow killer with some organics, so protection makes sense, even if the specific bottle isn’t especially photosensitive.

Label Clearly and Avoid Cross-Contamination

Half the lost time in shared lab spaces comes from mystery residues or poorly labeled vials. I always date and label each container with the exact chemical name, fresh from the manufacturer or not. Separate designated pipettes or spatulas reduce cross-contamination. Contaminants from careless sampling can make old bottles useless, and repurchasing isn’t cheap or quick. Keeping this simple discipline means experiments run cleaner, with less noise in the data.

Waste Not—But Dispose with Responsibility

Some labs still drain unused chemicals without thinking twice; it’s harder during audits, but the practice isn’t gone. Ionic liquids aren’t always easily biodegradable, and fluorinated groups add extra baggage for wastewater plants. I treat leftover trifluoroacetate solutions with respect, collecting them for specialized waste pickup. No one wants their project derailed by a slip-up that gets noticed by environmental health later on.

Using Experience to Raise Standards

Small habits form the backbone of storing tricky chemicals. From tightly sealed amber bottles in cool, dry cabinets to clear labeling, every step guards against failed syntheses and unnecessary exposure. It comes down to thoughtful care—putting a little extra into storage steps saves frustration for everyone down the line.

Real-World Lab Concerns with Ionic Liquids

In any busy research lab, you can spot a bottle of 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate sitting on the shelf. It’s one of those ionic liquids that chemists gravitate to for a good reason: it can dissolve cellulose and other stubborn biopolymers, opening the door for plenty of green chemistry experiments. But there’s a catch that often hides in the fine print. Mixing this chemical with other reagents doesn’t always go smoothly.

Why Compatibility Can't Be Ignored

Mixing chemicals always means risk, but ionic liquids present some extra twists. They have strong hydrogen bond-accepting ability, can form new phases with polar solvents, and show a stubborn resistance to simple separation after blending. In my own work, tossing 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate in with regular alcohols or acetone changed solution behavior more than expected. Instead of a clean blend, you get odd viscosities, sluggish extractions, or cloudiness that hints at deeper trouble.

Key Compatibility Trouble Spots

Mixing with strong acids like hydrochloric or sulfuric brings a real risk of decomposition. The trifluoroacetate anion can break down, giving off toxic fumes. Even weak bases interfere with the ionic structure. In one graduate project, adding potassium carbonate for a reaction ruined the ionic liquid, and what was left had a strange smell and zero reusability. Aromatic solvents, such as toluene or xylene, won't always dissolve the salt as expected. Some trials led to phase splits and would-be reactions stalling out halfway.

Mixing with strong acids like hydrochloric or sulfuric brings a real risk of decomposition. The trifluoroacetate anion can break down, giving off toxic fumes. Even weak bases interfere with the ionic structure. In one graduate project, adding potassium carbonate for a reaction ruined the ionic liquid, and what was left had a strange smell and zero reusability. Aromatic solvents, such as toluene or xylene, won't always dissolve the salt as expected. Some trials led to phase splits and would-be reactions stalling out halfway.

Water brings another headache. Even a little can lead to separation, drive phase changes, or drag out unwanted hydrolysis. Trying for biopolymer dissolution? Water slips in and suddenly, yield and purity drop due to the breakdown of either the sugar chain or the ionic liquid itself. These aren’t just side notes—they are pitfalls that turn months of planning upside down.

Supporting Safety with Solid Data

If someone figures “this looks safe, it’s just an ionic liquid,” it pays to check the growing stack of published work. A group in the journal Green Chemistry (2011) detailed how adding halides or even benign buffer mixtures steps up the corrosion risk for glassware. The Environmental Protection Agency points out that some fluoroacetates are toxic, so spills during phase-separations can end up much more destructive than anyone expects.

Smart Solutions for Blending Success

In any serious set-up, small-scale compatibility trials are the rule. A half-hour in the fume hood, using a glass vial to test for phase separation or detectable odor, beats running a full reaction blind. I also lean toward using online compatibility charts or open-source chemical safety platforms, asking peers for notes where possible. Ventilation, PPE, and clear labeling save time and stop emergencies before they start.

There’s no such thing as a one-size-fits-all solvent. 1-Hexyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate earns its spot in the toolbox, but mixing it carelessly with acids, bases, water, or aromatic solvents turns a promising project into a money pit. Dig into compatibility data, pay close attention to early-stage experiments, and the odds of disaster drop. That’s experience talking, and the literature backs it up.