1-Hydroxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hydrogen Sulfate: Insights, Progress, and Future Pathways

Historical Development

Chemists have spent decades searching for solvents and catalysts that can shift the ground rules of industrial chemistry. 1-Hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogen sulfate traces its roots to the rise of ionic liquids in the late twentieth century. Early breakthroughs in imidazolium-based salts opened doors to new, green solvents that broke away from volatility and flammability. Discovery often follows need, and the limitations of classic acids and bases in organic synthesis nudged researchers toward innovative alternatives. The emergence of 1-hydroxyethyl substitutions, first reported in the scientific literature in the early 2000s, shaped how the field viewed task-specific ionic liquids, especially when conventional solvents couldn’t deliver both selectivity and sustainability.

Product Overview

Here stands a molecule with a mouthful of a name: 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogen sulfate. Think of it as a customizable ionic liquid built on the imidazolium scaffold, with a hydroxyethyl tail welcoming hydrogen bonding and the hydrogen sulfate anion bringing Brønsted acidity. The substance is often delivered as a viscous, colorless to pale yellow liquid. In many ways, it feels a little sticky in the hand and sometimes has a faint odor reminiscent of sulfur. Manufacturers focus on purity, moisture content, and the absence of halide contamination—since all these factors shape catalytic strength and recyclability for industrial users.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Pour it from a glass vial and you’ll see a fluid that stands apart from ordinary solvents. Viscosity tends to run high, especially at room temperature, though it thins out with gentle heating. Typical densities fall around 1.2 to 1.3 g/cm³, and boiling points sit over 200°C, often with decomposition before reaching clear evaporation. This ionic liquid resists easy ignition and brings remarkable thermal stability. Water solubility is strong, and the hydroxyethyl group influences both polarity and hydrogen-bonding capability. In my own lab experience, this hydrophilicity enables creative routes in catalysis and extraction, while the acidity opens competitive alternatives to mineral acids in esterification.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

A vial’s label speaks volumes to those who understand the details. Producers commonly report molecular weight (about 236.28 g/mol for the pure salt), purity above 99%, water content less than 0.5%, and specific storage recommendations—usually sealed under dry, inert gas. Batch numbers and analytical certificates matter for research, given the sensitivity of many syntheses to trace impurities. Regulations push for clear hazard pictograms and signal words, since hydrogen sulfate components can corrode metals and irritate skin. Transport as a non-flammable, non-volatile chemical gives some flexibility, but handlers still respect its chemical reactivity.

Preparation Method

Lab-scale production usually starts with 1-methylimidazole and ethylene oxide or 2-chloroethanol for the hydroxyethyl group. After quaternization, the intermediate salt meets sulfuric acid—often under cooling, since the reaction liberates heat rapidly. Careful titration protects the intended stoichiometry and avoids runaway acidification. Filtration and multiple washings help purify the resulting ionic liquid, which is then dried under vacuum. Scale-up doesn’t majorly distort the procedure, though more attention goes to containment, heat management, and worker protection. It’s one of those procedures where hands-on attention to detail makes or breaks the product quality.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

This ionic liquid attracts chemists thanks to its strong Bronsted acidity and stable, design-friendly structure. The hydroxyethyl group lends itself to further functionalization, including etherification, sulfonation, or grafting onto polymers. Catalytically, it shines in esterification, alkylation, and dehydration reactions, often reducing the load of mineral acids and cutting corrosive side-products. Its acidity can be tuned by blending with other ionic liquids or by partial neutralization. These modifications extend activity across a wide range of synthetic steps, especially where conventional acids struggle with selectivity or recyclability. In the field, I’ve seen researchers create libraries of tuned ionic liquids by adjusting the hydrogen sulfate anion or modifying the imidazolium core.

Synonyms & Product Names

Walk through catalogs or online stores and you’ll spot this compound under several names, reflecting both IUPAC conventions and manufacturer branding. The core is 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogen sulfate, often abbreviated as [HEMIm][HSO4]. Some suppliers market it as hydroxyethylmethylimidazolium hydrogen sulfate or HEMIMHS. These variations show up in academic papers and patents, so a little research often clears up confusion. Trade names might stray further for marketing purposes, but researchers and buyers pay close attention to chemical abstracts and synonyms to avoid mix-ups.

Safety & Operational Standards

On the bench, the substance looks tame, but spill it on bare skin and you’ll feel irritation quickly, especially with prolonged exposure. Its hydrogen sulfate content raises the risk of corrosion for unprotected metal surfaces. Inhaling volatilized acid or fine aerosols presents respiratory hazards, even though true volatilization at room temperature stays low. Labs working with this ionic liquid wear gloves, protective eyewear, and sometimes face shields—especially during preparation or transfer of large volumes. Disposal protocols channel all waste into dedicated acid-resistant containers; dilution with water triggers exothermic reactions, so added caution keeps workers safe. Industrial handling leans on local safety regulations and best practices developed in the chemical sector to keep accidents out of headlines.

Application Area

In industry circles, the compound draws attention for its dual role as both a solvent and a catalyst. Biorefineries use it in the fractionation of lignocellulosic biomass and in the selective hydrolysis of polysaccharides. Petrochemical plants tap into its catalytic power for desulfurization and alkylation, improving both yields and waste management. Fine chemical labs exploit its selectivity for Fischer esterification and Friedel–Crafts alkylations, often reclaiming and reusing it across dozens of cycles. Researchers working on pharmaceuticals have tested its use for chiral separations and enzyme stabilization. Its green profile fits well into the growing demand to replace volatile organic solvents with safer, recyclable options.

Research & Development

Publishers brim with studies tweaking the cation or anion to balance acidity, thermal stability, viscosity, and chemical compatibility. Some teams focus on immobilizing the ionic liquid on polymers for easier recovery. Others push the envelope by blending it with other functionalized salts to dial up precision catalysis or enhance membrane separations. My own experience with collaborative R&D teams highlighted the constant push-and-pull between maximizing activity and simplifying recycling—two priorities that don’t always align. University and corporate groups regularly publish new approaches to synthesize derivatives with either higher catalytic activity or greater tolerance for water and organic substrates. The best ideas usually come from cross-disciplinary work among chemists, engineers, and environmental scientists.

Toxicity Research

Ionic liquids bring hope for safer industry practice, but toxicity cannot be brushed under the rug. Animal studies and aquatic models highlight moderate acute toxicity for this class—less than traditional acids, though not benign. The hydroxyethyl group produces some biodegradability, yet high concentrations in waste streams challenge standard water treatment plants. Chronic exposure effects warrant further scrutiny, especially as scale-up increases environmental load. Guidelines urge controlled handling, use of secondary containment, and avoidance of open drains. Ongoing studies evaluate long-term impacts on soil microbes and aquatic systems. As with most chemicals, thorough risk assessment and environmental monitoring determine how broadly the technology takes root.

Future Prospects

Innovation in sustainable chemistry rides on the back of compounds just like 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogen sulfate. As industrial processes inch away from corrosive mineral acids and flammable solvents, designers count on ionic liquids to bridge gaps between safety, performance, and recyclability. Real progress means scalable recoveries, straightforward purification, and more predictable end-of-life cycling. Research momentum continues to swell around custom functionalization, tandem catalysis, and integration with renewable feedstocks. Regulations will shape the path forward, especially as data about toxicity and environmental persistence emerges from laboratory and field studies. In my view, partnerships among academia, industry, and regulators offer the best route to grow benefits while steering clear of unintended consequences.

A Quiet Giant in Green Chemistry

1-Hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogen sulfate sounds like a mouthful, but this ionic liquid brings big changes to a handful of industries that shape the modern world. Labs started to lean into ionic liquids like this one for the same reasons I see chemists’ eyes light up: no nasty fumes, low flammability, and a handshake with sustainability efforts. Seeing this firsthand, it’s clear why these liquids move beyond the pages of academic research and step into real manufacturing.

Cleaner Catalysis for Organic Synthesis

Organic chemists always seem locked in a tug-of-war with solvents and catalysts. Traditional solvents rush to evaporate, taking both your product yield and health with them. In a mid-sized lab, harsh solvents can trigger a pile of headaches—both literal and regulatory. Here’s where 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogen sulfate stands out: as a solvent and catalyst for transformations such as esterifications, alkylations, and transesterifications. Instead of chain-smoking through toxic chemicals, chemists can use this ionic liquid to drive reactions faster and grab higher yields. The reusability also gives labs less waste, cutting back on cost and disposal headaches.

Cellulose and Biomass Processing: Modern Answers to Old Problems

I spent a summer in a lab trying to dissolve cellulose, battling every cocktail of solvents out there. Traditional options struggle, but this ionic liquid melts plant fibers down, giving easy access for biofuel production and advanced materials. Now, timber and agricultural waste can turn into valuable products. That brings ethanol closer to everyday drivers and puts new bioplastics on the market.

Electrochemistry Gets a Boost

Electrochemists face constant issues cooling batteries and stabilizing electrodes. 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogen sulfate resists breaking down at high temperatures and replaces the volatile liquid electrolytes that cause more problems than they solve. Improved conductivity and reliability show up in batteries, fuel cells, and capacitors. Think longer-lasting power for electronic devices and fewer thermal runaways. Here in the energy storage world, every bit of safety and stability counts for both industry-scale solutions and the smartphones in our pockets.

Acidic Cleaners and Extractants

Industrial pickling and cleaning uses harsh acids, causing corrosion and worker safety issues. With this ionic liquid, you get strong acidic properties without the noxious fumes. It lifts metal oxides from surfaces and extracts metals from ores and electronic waste. The recycling world—especially for rare earth elements and battery metals—sees these liquids as a way to get more out of the same scrap while keeping the workplace air clearer.

Some Hurdles Remain

While these applications pack a punch, cost and production scale still limit how far this ionic liquid can spread. Labs benefit from smaller batches, but manufacturers looking for ton-scale commodity chemicals lean toward cheaper, old-school solvents. Ongoing research points to smarter synthesis and recycling to drop prices and waste. With broadening use in pilot projects, real-world feedback gives manufacturers blueprints for larger factories.

Moving Toward a Safer, Smarter Future

The chemical world chases solutions that improve safety, cost, and sustainability. 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogen sulfate already unlocks more efficient pathways for fuels, materials, batteries, and green manufacturing steps. Scaling up will take teamwork between academic labs, industry partners, and regulatory agencies. The next chapter depends on how quickly costs drop and how open companies remain to rethinking decades-old processes.

Understanding the Substance

1-Hydroxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hydrogen Sulfate sounds like a mouthful, but it’s one of a group of chemicals often used in chemical labs, some types of manufacturing, and even for research into green chemistry since it’s an ionic liquid. These substances usually get attention for their ability to dissolve tough materials and their use in separation processes, so the question of safety is never far behind.

The Risks in Working with Unknowns

Little hands-on experience with chemicals like this one always brings me back to chemistry lab safety briefings in grad school. A liquid that isn’t well-known in popular safety literature sometimes gets handled with too much confidence. It rarely occurs to people that many ionic liquids, while they aren’t volatile, still carry their own risks, especially when it comes to skin contact and accidental inhalation.

The chemical structure of 1-Hydroxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hydrogen Sulfate means it belongs to the imidazolium ionic liquids family. Many of these come with warnings about skin irritation, eye damage, and potential toxicity if swallowed. Hydrogen sulfate groups are acidic and corrosive; spilling this on yourself can cause burns or chronic irritation. Inhaling fumes from strong acids—even in ionic form—has brought plenty of researchers to the campus health office over the years. Toxicity data remains sparse, adding a layer of uncertainty. People sometimes underestimate substances that don't smell or evaporate easily; just because it doesn't sting your nose doesn't mean it won't cause harm.

Practices That Matter

In my experience, safety always improves when clear habits kick in early. Proper gloves and safety goggles form the basics. Splash-resistant lab coats and closed shoes come next. Handling happens under a fume hood—not just for the person handling the chemical, but for anyone sharing that workspace. Avoid rushing; methodical transfer and weighing limit spills. Washing hands right after use sounds obvious, but plenty of colleagues skip that step when things get busy.

Many chemicals sneak into cracks between gloves or leak as fine droplets; double-gloving sometimes makes sense, especially when handling potential skin irritants. If the bottle stays open longer than necessary, vapors can accumulate—even with so-called “non-volatile” liquids. Lab ventilation isn’t just for show; keeping air moving stops accidental exposure before it begins.

Anyone storing this chemical needs clear labels with hazard markings. Storing acids away from bases and organics is a no-brainer, and keeping a spill kit nearby with neutralizing agents helps minimize panic when accidents do happen. Talking with coworkers about near misses and experiences, rather than hiding mistakes, creates a safer environment. Some of the most valuable lessons in lab safety don’t show up on the safety data sheet.

Hard Facts and Solutions

Scientific studies on imidazolium-based ionic liquids have flagged diverse toxicity profiles. Some are mild irritants, but others disrupt aquatic life and linger in the environment. Landfills and drains don’t solve disposal problems—these chemicals need collection and disposal through a licensed hazardous waste provider. A supplier’s MSDS often states the basics, but direct peer-reviewed toxicity studies sometimes raise new issues that later affect workplace policy.

Training new staff on hazards, clear labeling, and working under supervision until routines become second nature limits risk. As more chemicals like this enter the workplace, ongoing education makes a difference. Regulatory agencies keep tightening their standards for handling novel ionic liquids thanks to mounting evidence of cumulative risks. Relying on old habits is never enough—it always pays to see each new substance as a fresh challenge that deserves attention and care.

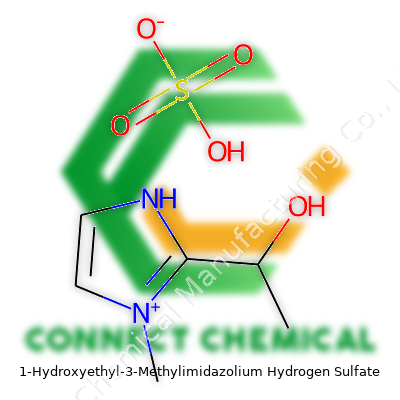

Understanding the Structure

1-Hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogen sulfate looks complicated on paper, but the structure backs up its reputation as a useful ionic liquid. The cation consists of an imidazolium ring with a methyl group on one nitrogen and a hydroxyethyl group on the other nitrogen. Add to this the hydrogen sulfate, which acts as the anion, and you see why the compound remains both stable and versatile.

Chemically, the cation forms like this: the imidazole ring (C3N2H4) gains a methyl group (–CH3) and a 2-hydroxyethyl group (–CH2CH2OH). The anion pairs up as hydrogen sulfate (HSO4−). The full molecular formula is C6H11N2O5S.

The molecular structure delivers a real impact in laboratories and industry. Researchers in the field of green chemistry know this ionic liquid for its strong solvating abilities and stability under many reaction conditions. Having tinkered with plenty of solvents myself, I’ve found that this one usually doesn’t react with glassware and resists decomposition at moderate temperatures, making it less of a headache during extended syntheses.

Molecular Weight

Adding up the atomic weights:

- Carbon: 6 × 12.01 = 72.06

- Hydrogen: 11 × 1.01 = 11.11

- Nitrogen: 2 × 14.01 = 28.02

- Oxygen: 5 × 16.00 = 80.00

- Sulfur: 1 × 32.07 = 32.07

Real-World Significance

This ionic liquid brings big advantages over traditional solvents. Its low volatility and lower toxicity cut the risk to lab workers and the environment. Many who work in research get tired of sharp-smelling solvents and their health warnings. Substances like 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogen sulfate give a safer alternative that keeps air clean and reduces exposure.

The ability to tune ionic liquids through different substituents – adding bulk here, a functional group there – lets chemists control solubility and selectivity. If you need a stronger acid, the hydrogen sulfate anion steps up. If you demand a mild environment, the imidazolium cation keeps reactions stable.

There’s a cost consideration. Manufacturing ionic liquids in bulk gets pricey, and not every reaction benefits from using them. Balancing upfront costs against gains in safety, reusability, and disposal is something industrial chemists deal with every day. I once helped assess waste streams for a small process, and ionic liquids, although initially more expensive than old-school solvents, made up for it through reduced hazardous waste fees and easier recycling protocols.

Moving Toward Solutions

Scaling up production calls for process tweaks, greener synthesis methods, and perhaps better sourcing for the sulfate. Industry has begun recycling used ionic liquids, which helps shave costs and keeps resource consumption down.

Long-term, development in this area depends on a steady supply of raw materials and buy-in from users. Students learning organic synthesis should spend more time with ionic liquids like this one to get comfortable using modern, safer solvents that meet both performance needs and stricter environmental standards.

Based on what I’ve seen in research circles, as we shift toward a more sustainable chemical future, compounds like 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogen sulfate will keep pulling their weight across labs and factories. It’s all about safer options and smarter chemistry.

Practical Storage, Real Risks

Watching over chemicals like 1-Hydroxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hydrogen Sulfate goes beyond keeping the bottle closed and the shelf tidy. Years spent among lab shelves and fume hoods have taught me this: Some ionic liquids act stable, but they don’t forgive carelessness. Moisture, oxygen, and heat test the patience of this substance. Tossing it just anywhere makes trouble down the road, both in purity and safety.

Humidity Wrecks Stability

Water never belonged in a bottle of this ionic liquid. It’s hydrophilic, which means even city-lab humidity draws water right through loose stoppers or damaged seals. With each gram of water creeping in, the consistency and chemical properties change, dragging down any experiment’s reliability. Units with ongoing projects know that once contamination sneaks in, reproducible results vanish. A tight seal matters, but so does a truly dry atmosphere. People with serious experience use desiccators or even dry boxes. For small stocks, vacuum-sealed vials cut risk. A silica gel pouch next to each bottle isn’t a gimmick — it’s common sense.

Heat and Sunlight: Quiet Thieves

Heat can speed up the breakdown of 1-Hydroxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hydrogen Sulfate. Sunlight doesn’t help, either; direct UV can stir up unwanted chemical changes. A colleague once left several ionic liquids on a bench next to a window, and over a few days, color shifted and strange odors appeared. Lost product, lost data, and a dented reputation. Decent chemical cabinets shield supplies from sunlight. Fridges help, as long as they stay above freezing and avoid other incompatible or reactive material. Some labs push for cool, temperature-controlled storage at 4–8°C, mainly because it slows spoilage and keeps breakdown at bay.

Air Exposure and Oxidation

Air exposure brings its own set of problems, not just from dust but from oxygen. Over time, oxidative processes change the compound. I’ve seen impure batches become unusable just because the caps weren’t replaced after routine use. This might sound over-cautious, but even a few hours outside a sealed vial tilts the risk. In larger operations where constant opening is needed, nitrogen or argon blankets add an extra layer of protection.

Sensible Labeling and Segregation

Mislabeling or ignoring storage protocols results in wasted hours and costly mistakes. A fresh label on every bottle, including the date opened, keeps track of potential degradation. Guidance pushed by chemical safety authorities underscores the value of storing acidic ionic liquids away from anything that reacts with acid or releases bases. Segregation on storage shelves prevents accidental cross-contamination — a simple shelf divider can make a day easier and safer.

Solutions Come from Habits, Not Just Hardware

Manufacturers may offer technical tips, but the truth is that consistency in daily practice does more for stability than any fancy container. A shared calendar for reagent checks, routine weighing to catch evaporation losses, and periodic purity tests keep surprises to a minimum. It’s not just about following rules but about treating each bottle as an investment in future results.

Facts that Guide Choices

According to peer-reviewed sources published in journals such as Green Chemistry and Chemical Reviews, 1-Hydroxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hydrogen Sulfate degrades more quickly in humid, warm, or light-rich environments. Shelf life can drop from over a year in cold, dry, dark spaces to just weeks on warm, open benches. Hazardous substances regulations in major countries agree on the importance of storing reactive acids in dedicated, labeled cabinets.

Every Bottle Tells a Story

The real cost of mishandling this ionic liquid isn’t just wasted money; it’s the cutting corners that catch up at the worst moment. Experience in chemical labs confirms: Stability comes from smart storage, routine habits, and direct attention, not by accident. Every technician, researcher, or QC analyst benefits from making the right call every time the bottle leaves the shelf.

Understanding the Purity Range

In the world of ionic liquids, 1-Hydroxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Hydrogen Sulfate stands out as a workhorse, especially in organic synthesis and biomass processing. Most suppliers label this compound at 98% purity or higher. From experience in the lab, reaching this level isn’t only about running the right reaction—post-synthesis purification and careful storage matter just as much. Water content, for instance, creeps in easily and drags actual purity below what’s claimed if people aren’t careful.

Even well-packaged samples can pick up trace moisture. Karl Fischer titration usually tells the real story—moisture hovering from 0.1% up to 1% for samples stored carelessly. That might look small on paper, but engineering with solvents at scale, 0.5% water can make reactions sluggish or shift selectivity.

Common Impurities in the “Purified” Stuff

Some folks look at the lot’s sticker purity and assume nothing else gets in. It’s rarely that tidy. Several predictable impurities show up—leftover 1-methylimidazole and unreacted 2-chloroethanol ring a bell from my time purifying batches with students. Residual starting materials cling in small amounts unless purification gets aggressive with distillation or chromatography. Simple extraction won’t always cut it, especially for someone trying to scale from a benchtop gram to a business-sized drum.

Other persistent hangers-on: sulfate ions can linger in higher than desired amounts, especially if the protocol rushes the acid addition step or uses low-quality reagents. Neutralization byproducts also crop up, mainly inorganic salts if purification skips a proper aqueous workup. Overlooking trace metals from glassware or stir bars crops up in analysis on sensitive NMR or ICP-MS. These don’t bust a synthesis at small scale, but they wreck reproducibility downstream or foul up a catalytic system.

Risks Lurking in Impurities

Someone just glancing at a chemical’s purity kit might not feel the impact, but lingering water, neutral organics, or trace metals turn simple synthesis thorny. Hydrogen sulfate ionic liquids already grab water fast—they’re hygroscopic by nature. Additional water takes away the edge in dissolving reactants predictably or swings pH outside intended range. In enzyme-related work, a hair more inorganic contamination can cut enzyme life or alter product selectivity. While running bioconversions in college, I learned how persistent even tiny levels of chloride or iron can be.

High-purity ionic liquids should mean safety from regulatory headaches or batch recall down the line. Anyone running pilot projects or prepping pharmaceutical intermediates banks on reliable specs. A colleague’s new process for converting lignin derivatives fell apart until adjusting for trace acid in what was “98% pure.” Those headaches stick if ignored at the outset.

How to Tackle Impurities

Real solutions start with closing the loop on purification. Anyone shooting for the closest to theoretical purity keeps ionic liquids dried under vacuum over molecular sieves—desiccators aren’t enough. I recommend batch analysis by NMR for organic leftovers, and by ICP-MS or ion chromatography for metal and ionic contaminants. Careful suppliers include these trace impurity data in their certificates, but double-checks by end users make sense.

Switching to glassware cleaned with acid and dedicating tools for ionic liquid work reduces cross-contamination. Layered purification steps—use of charcoal, silica gel, and repeated extraction—push quality further than a single textbook method.

From bench chemist to process engineer, cutting corners around purity and ignoring hidden impurities will bite back eventually. Upfront investment in verifying actual composition rewards everyone with repeatable results and fewer surprises at scale.