1-Hydroxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate: World of an Unconventional Ionic Liquid

Historical Development

Stories in the world of ionic liquids don’t just begin with a lab protocol and some white powder in a glass vial. Over the past 30 years, research teams everywhere from Beijing to Berlin began tuning the structure of imidazolium salts, searching for ever-more-useful room temperature ionic liquids (RTILs). Their motivation was clear: solvents that don’t evaporate, won’t burn, and dissolve a huge range of compounds transform both green chemistry and old-school industrial processes. 1-Hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, usually called [HEMIM][BF4] or HEMIM BF4, emerged from this storm of synthesis, showing off a mix of practical viscosity, moderate toxicity, and strong solvating ability.

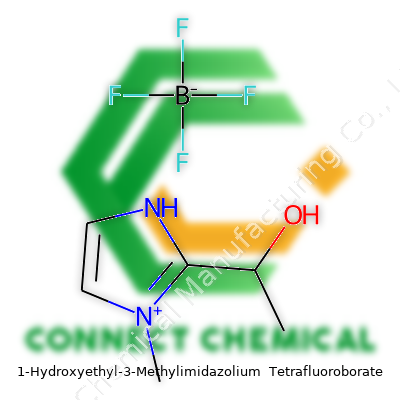

Product Overview

Put a small vial of 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate in your hand and you might notice it doesn’t smell like much—the hallmark of a low vapor pressure solvent. This clear, colorless to pale yellow liquid stands out in the crowd of ionic liquids because of the hydroxy group attached to the ethyl arm of the imidazolium ring. The structure grants it a bit more hydrogen bonding compared to the standard 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium salts. Labs and industries buy it for use in electrolytes, extraction processes, and as a modifier in catalysis.

Physical & Chemical Properties

The tetrafluoroborate anion brings stability, which means bottles sit safely at room temperature. The liquid runs a bit thick but pours easily enough. Density sits around 1.24 g/cm³, and thermal stability stretches well past 150°C. Water dissolves it without much fuss, and the melting point typically stays below -15°C—one reason the stuff stays liquid on the bench. Its high ionic conductivity and wide electrochemical window matter for those building supercapacitors and batteries. The hydroxyethyl side chain pulls polar molecules and keeps the solvent miscible with polar solvents, adding another layer of flexibility for researchers.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Bottles shipped from chemical suppliers will often promise a purity above 99%. Labels should include the CAS number 646860-51-7, a molecular formula C6H11BF4N2O, and warning icons showing its irritant status. Safety Data Sheets (SDS) insist on gloves and goggles for handling. The regulatory status lands squarely in the “research-only” realm—most jurisdictions don’t approve it for medical or food applications yet. Labs keep it under nitrogen for long-term storage to avoid moisture pickup, as the hydroxy group and BF4 anion both like water more than most.

Preparation Method

Synthesizing 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate follows a standard two-step ionic liquid route. Chemists start with imidazole, methylate it at the N3 position, then alkylate the N1 position using an epoxide like ethylene oxide. After forming the 1-hydroxyethyl chain, they add tetrafluoroboric acid, which swaps the initial halide for the stable BF4 anion. Crude product goes through washing to remove unreacted starting materials and salts, then vacuum distillation strips out water and light impurities. The process needs careful control of temperature, as overheating can decompose the product or create hazardous byproducts from the BF4 group.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The real value in this ionic liquid comes from the hydroxy group hanging off the cation. That part serves as a “handle” for more advanced chemistry—derivatizations, click reactions, polymerizations, and even cross-coupling catalysis. Sometimes researchers will swap the BF4 anion for others, like PF6 or NTf2, each offering different levels of hydrophobicity and electrochemical window. The parent compound supports a wide range of reactions, acting as both solvent and phase transfer catalyst in Suzuki, Heck, and other transition metal-mediated processes.

Synonyms & Product Names

In catalogs, you will see 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, [HEMIM][BF4], HEMIM BF4, and simply Hydroxyethyl-imidazolium BF4. Trade names might run longer or shorter, but those seeking this material for an experiment usually find it listed under one of these five permutations.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling ionic liquids isn’t the wild west, but it’s nowhere near the world of table salt. This compound irritates eyes and mucous membranes, so most protocols require chemical-resistant gloves, splash goggles, and working under a hood. On skin, even small spills cause redness or itching for sensitive folks. The BF4 anion doesn’t play well with strong acids or bases, which release toxic fluorine emissions—clearly labeled fume hoods are mandatory. For spills, labs use dedicated absorbent pads and avoid contact with aluminum, which reacts with many BF4 salts. Waste goes in special containers marked for halogenated organics.

Application Area

Researchers and industry engineers reach for 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate when conventional solvents like DMSO or acetonitrile fail either for toxicity or volatility. Its greatest strength lies in electrochemistry—supercapacitor prototypes, battery electrolytes, and dye-sensitized solar cells all shoot for ionic liquids with stable, wide voltage windows. Extraction chemists separate rare earth metals or pharmaceuticals from water with it, beating most non-volatile solvents on speed and selectivity. As an additive in transition metal catalysis, the hydroxyethyl arm can sometimes stabilize intermediates or even accelerate reaction rates. Some green chemistry protocols favor this solvent for biomass processing thanks to lower vapor emissions compared to classic industrial chemicals.

Research & Development

Academic groups and corporate R&D teams both stake out new ground using this ionic liquid. They have used in situ NMR, FTIR, and Raman spectroscopy to pin down its solvation properties and reaction profiles. Studies have mapped out the best parameters for lithium-ion and redox-flow battery electrolytes, showing substantial gains in cycle life or charge capacity compared to older solvent systems. Meanwhile, a steady march of papers trace new modifications of the hydroxy moiety, seeking “designer” ILs with even broader application ranges. Several grant-funded projects target more robust biodegradation pathways for the tetrafluoroborate anion, aiming to minimize environmental legacy as these chemicals leave the bench and enter larger-scale operations.

Toxicity Research

While 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate sharply reduces fire risk compared to traditional organic solvents, researchers cannot ignore the possible toxicity. Cell culture experiments indicate moderate cytotoxicity—lower than the classic imidazolium cations, but higher than sugar-based ionic liquids. Aquatic studies highlight lingering persistence and potential adverse effects on aquatic organisms at higher concentrations. The BF4 anion might break down into boron and fluorine-containing species under harsh conditions, but most typical use sees it stay intact. Regulatory bodies in Europe and Asia recommend environmental controls to keep ionic liquid emissions tightly contained.

Future Prospects

Interest keeps building for 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate as governments and industries ditch high-volatility solvents for greener, fire-resistant options. Ongoing work focuses on tuning the hydroxyethyl handle, switching out or modifying the counterion, and blending this ionic liquid with polymers for next-generation actuators and solid-state electrolytes. Some groups investigate recyclable or degradable alternatives to both the imidazolium core and the BF4 anion. The goal is a solvent as green as possible, with industrial strength for extraction, synthesis, and energy storage—minus the environmental hangover. This compound stands at an interesting crossroad, ready for more advanced study and industrial trials as safety guidelines and sustainable processes catch up with its potential.

A Modern Tool for Green Chemistry

Anyone following advances in chemistry has seen a growing spotlight on ionic liquids, with 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate often coming up as a standout choice. This compound has developed a strong reputation, especially among researchers trying to cut down on environmental waste. Its main draw comes from the fact that it stays liquid at room temperature, which makes it less risky in everyday handling compared to older solvents that evaporate and cause pollution.

Applications in Organic Synthesis

Chemists wearing their synthetic hats will know how tough it is to run reactions cleanly, safely, and with minimum waste. This ionic liquid replaces traditional volatile organic solvents, which means you see cleaner air in labs and less risk of dangerous by-products. For instance, using this compound in alkylation and polymerization reactions reduces the need for hazardous chemicals, and its stability under heat gives more flexibility during long runs. Research out of universities and chemical companies points out that yields frequently rise compared to typical solvents.

Electrochemical Devices

Mixing electricity with chemicals gets complicated quick, and keeping things stable over time is tough. In supercapacitors and lithium-ion batteries, this ionic liquid serves as a solid electrolyte. It doesn’t easily evaporate or break down during cycles, which means batteries can last longer and leak less. Data from testing labs show that it even allows charge to flow smoothly at higher voltages than water-based or old-school organic formulas. This has helped fuel new rounds of research into safer and lighter energy storage, especially for mobile electronics.

Biocatalysis and Enzyme Work

This ionic liquid often appears in enzyme-based processes. Normally, traditional solvents break down proteins or limit how well enzymes can do their job. Scientists have noticed that 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate lets enzymes work at higher rates for longer periods, which matters if you’re trying to make medicines or food ingredients with less chemical waste. Published studies out of the biotech sector confirm that enzymes hold up better, producing higher-quality results without nasty side-effects or by-products.

Environmental Cleanup

Across city labs and industrial settings, cleaning up metal ions—think waste from plating companies or electronics factories—presents a real headache. This ionic liquid works as a powerful extraction tool. When dealing with heavy metals like copper, lead, or chromium in water, it can draw out contaminants without mixing in new toxins. Real-world pilot tests show that waste water treated with this chemical meets tight public health guidelines quicker and with less downstream processing.

Stepping into the Future

People in the chemistry industry look for practical, safe, and affordable solutions. As more regulations limit old solvents and call for gentler processes, this ionic liquid seems poised to stay important. Labs have started shifting toward recyclable solvent systems, reusing this compound after filtering or distillation. These efforts cut down on hazardous waste and lower overall operating costs, which matters for both startups and legacy manufacturers. In my experience, a shift to ionic liquids like this always sparks new ideas in the lab—hybrid solutions, greener reactions, and better yields keep pushing the envelope.

Hands-On Reality of Lab Chemicals

Working in labs, I’ve noticed that a chemical name can look intimidating or harmless, but you never really know until you check its actual risk profile. 1-Hydroxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate fits this description. On paper, it falls under the broad family of “ionic liquids,” which get used a lot for green chemistry, separation science, and energy storage. Some folks pitch ionic liquids as safer than the flammable organic solvents they replace, and they often don’t evaporate easily. That doesn’t mean they’re risk-free or you can get lax—or else trouble follows.

Hazards Too Easy to Miss

Digging through safety data, this compound doesn’t jump out with wildly toxic warnings, but trouble comes in subtler ways. It won’t boil away and fill the air like acetone, but spills stick around and might sneak through thin gloves you’d use for ethanol. Tetrafluoroborate gets attention because, under the right conditions, it can let loose hydrogen fluoride if heated or hydrolyzed. Anyone who has messed with HF knows a drop means real pain—and possible hospital time. Even outside the worst-case scenarios, ionic liquids often cause skin and eye irritation or sneaky respiratory discomfort if you breathe in aerosols for too long.

Common-Sense Handling Matters

Personal experience taught me that complacency breeds accidents. One time, I watched a seasoned scientist handle a similar liquid wearing torn gloves, convinced “green” meant harmless. Several days later, chronic skin rashes cropped up. Turns out, longer exposure makes a difference, even if nothing dramatic happens right away.

Wearing impervious gloves, not just thin nitrile, actually matters here. Eye protection needs to cover the sides—splashes do happen, especially when transferring from commercial containers. If people get the stuff on their skin, washing right away with a lot of water cuts down the risk. Ventilated hoods make a difference, especially when heating or mixing with acids, because even slow vapors or accidental heating might send off hazardous gases. I always kept a tube of calcium gluconate gel for emergencies around anything with boron and fluoride, since it provides fast first-aid for fluoride exposure. The stuff seems expensive until you need it.

Labeling, Storage—Never Skimp

One big mistake comes with casual storage—stashing ionic liquids in a warm office or random drawer. Even if the original bottle says it's fine at room temperature, I stick to cool, dry storage with tight labeling, so nothing leaks or reacts with ambient moisture. Never blend reagents unless you’ve checked reactions—tetrafluoroborate can break down with strong bases or acids, and an innocent shelf-mate can become a problem starter after a long weekend.

No Shortcuts for Safe Lab Culture

Folks often remember safety for big/explosive compounds but let their guard slip around “new green” chemistry. Encouraging direct safety training helps—nothing beats practicing spills with fake ice tea (or water with dye). One-on-one coaching and repeat walkthroughs reinforce safe habits, more than the thickest binder of SOPs.

Building Better Choices

Researchers want cleaner, sustainable chemistry, which makes ionic liquids seem attractive. Ongoing research should keep digging into what happens after repeated exposure—long-term toxicology for these compounds remains sparse. Industry and academia both need to report accidents or near-misses, so future safety sheets match reality on the bench. A new material always promises benefits, but cutting down on risk never goes out of style.

Stability Depends On Good Habits

Anyone working with ionic liquids learns quickly that storing these chemicals is key for safety and for keeping their properties intact. 1-Hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, often called [HEMIm][BF4], falls squarely into this category. I remember the first time I opened a bottle in the lab, just how easily a little moisture from the room air could cloud the solution. This hydrophilic nature gives away one of the biggest challenges — water can degrade ionic liquids, and in this case it can throw off experimental results or weaken what makes the compound special.

Water—The Friend You Want To Keep Far Away

My first supervisor always drilled home the need to store ionic liquids in a dry environment. For 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, even a few drops of moisture can start breaking down its benefits, including conductivity and chemical stability. On top of that, tetrafluoroborate as an anion tends to hydrolyze, especially if left open to humid air. You can end up with toxic byproducts like boron trifluoride or even very corrosive acids.

We always used tightly sealed amber glass bottles, sometimes topped with a layer of inert argon gas if we valued the batch. Even a loose screw cap could mean trouble in wet or steamy labs. I’d suggest storing it in a desiccator packed with fresh silica gel or molecular sieves. Every time the bottle opened, you lose just a little more purity to the room — and that adds up over long-term storage.

Light, Temperature, and Chemical Neighbors

Light creeps up as another hidden threat. I saw injectable samples lose their clarity and performance simply by sitting under fluorescent lab lights for a few days. Ultraviolet exposure, and even strong ambient light, speeds up the breakdown process. Keeping storage bottles in dark cabinets makes a difference, or better, grab some amber-tinted glass which blocks most stray UV rays.

Temperature swings also cut into shelf life. High heat can accelerate decomposition, pump up pressure inside the bottle, or cause unexpected reactions. In our group, we stuck to room temperature, kept bottles out of direct sun, and used warning labels to keep them out of high-traffic hot zones like windowsills or near heat sources. Never freeze ionic liquids unless the supplier recommends it — low temperatures can change their crystalline structure or knock their properties out of balance.

Small Steps To Make Labs Safer

Keep it isolated from bases, strong acids, or anything you wouldn’t want mixing if a bottle tips over. I always separate hygroscopic chemicals into their own closed cabinet; one spill can start a chain reaction of contamination. Safety Data Sheets from most chemical suppliers flag the risk of toxic decomposition, making gloves, protective eyewear, and working in a well-ventilated fume hood much more than just a checklist item.

1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate offers exciting promise for green chemistry and unique industrial processes, but only when it’s stored right. Taking the extra steps to safeguard it from water, light, heat, and incompatible chemicals guarantees that properties stay reliable and workers stay safe. In my experience, careful attention to a chemical’s quirks saves time, money, and headaches later. That’s a habit worth building.

Understanding the Nature of the Chemical

1-Hydroxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate tends to show up in discussions about ionic liquids and green chemistry. Folks are drawn to these salts because of their low volatility and thermal stability. The cation in this one, an imidazolium ring, usually plays nicely with other chemicals in terms of blending. The tetrafluoroborate anion brings some added stability but also raises flags about what it can do when it meets water or bases.

Key Compatibility Issues Seen in Practice

I’ve worked on teams mixing ionic liquids with solvents, acids, and metals, and one thing that always comes up is water reactivity. Tetrafluoroborate anions break down when water sneaks in, especially at higher temperatures or if traces of acid or base join the party. That breakdown releases HF—hydrogen fluoride—which nobody wants around. Even in fairly dry conditions, mixing with strong alkaline chemicals turns risky. You can get unwanted reactions, making it clear you can’t assume this salt will stay stable everywhere.

Pairing this ionic liquid with strong oxidizers never went smoothly for us. In the lab, oxidation breaks the imidazolium ring or creates noxious byproducts. So if you’re thinking of using it with things like concentrated nitric acid or peroxides, it’s time to reconsider.

Metal ions bring their own challenges. Certain metal salts react with the tetrafluoroborate, often precipitating or forming new, sometimes unpredictable, compounds. Copper and silver salts, in particular, don’t mix well. We lost a batch once after seeing a cloudy mess instead of our expected product when combining these. Compatibility screening on small scale always wins over wishful thinking.

Real-World Importance for the Lab and Industry

Some manufacturers sell this compound because it dissolves cellulose or supports electrochemical reactions. Still, scientists I know double-check the full chemical profile before scaling up. Even trace contaminants in commercial batches, like chloride or moisture, shift outcomes. I once saw an entire project’s yield drop by half over supposedly “minor” impurities.

Regulation adds another layer. Though the tetrafluoroborate group isn’t classified as highly dangerous on its own, breakdown products like HF fall under tight restrictions. Anyone handling this chemical has to consider not just their own safety, but also that of the environment. Proper ventilation, gloves, and regular pH checks on waste streams come standard in the better labs and plants.

Fact-Based Guidance and Better Choices

Chemists who want to get repeatable results screen new reaction partners before trying this salt in earnest. Compatibility charts help, but running a test reaction with real feedstocks provides real answers. In industrial cases, full process reviews detect places where moisture or other triggers can sneak in.

Some researchers now turn to alternate ionic liquids with more robust anions, like bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide, which stands up to impurities and temperature swings better than tetrafluoroborate. This move doesn’t solve everything, but it reduces some of the more notorious failure points.

Careful sourcing—buying from suppliers who deliver with quality certificates and low residual moisture—helps reduce variables. Where possible, teams install on-line monitors for pH and other indicators to catch trouble before it escalates.

After working with ionic liquids and seeing projects stall because of hidden compatibility issues, I see real value in building a work culture that treats every new input with skepticism at first. With a chemical this sensitive to both process and context, only vigilance and practical prep keep things running right.

Purity Isn’t Just a Number—It’s a Promise

Anyone regularly working with ionic liquids will recognize that purity isn’t just about hitting a percentage on a datasheet. Manufacturers usually aim for at least 99% purity for 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, often advertising it with specifications like “≥99%” or “99.5%.” This isn’t overkill. Trace impurities, especially water or chloride, can throw off sensitive applications, skew results in catalysis, or damage electrodes in electrochemical setups. If you’re running a process that’s sensitive to moisture content, searching for values under 0.5% for water makes sense—and some trusted suppliers produce even tighter specs, giving you more confidence.

Throughout years spent in labs, nothing highlighted the practical importance of purity like watching supposedly minuscule contaminants cause headaches in what should’ve been a routine reaction. Impurities become costly beyond the bottle price when they lead to failed syntheses or wasted time. That’s why solid QA documentation—complete with detailed certificates of analysis—counts for more than a glossy datasheet.

Packaging Choices Reflect Real-World Needs

Suppliers typically provide 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate in glass bottles for lab-scale quantities, commonly ranging from 25 grams up to 500 grams. Industrial customers often request larger formats—one-kilogram bottles, five-kilogram containers, or even metal drums. Storage choices can seem like small details, but they shape workflow. Take it from anyone who’s ever fished for the last crystals from a bottle too small for the pipette or struggled with a container that let moisture seep in.

The practical side of packaging deserves respect: glass protects against the corrosive nature of ionic liquids and helps keep out unwanted humidity. Larger operations sometimes ask distributors for custom packs, like high-integrity HDPE drums sealed with PTFE, to minimize atmospheric exposure. In my experience, the occasional call to a supplier requesting non-standard packaging always boils down to this: reliability and consistency during ongoing projects.

Why Detailed Specs Deliver Real Value

It’s easy to take for granted the detailed information lists: melting point, density, and degradation temperature. Working on projects that push solvents near their thermal limits drives home the need for up-to-date, accurate data. 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate finds uses from separation science to green synthetic routes. Without honest handling of water and chloride content, the whole “green” pitch crumbles before the project even begins.

Most reputable producers update their safety sheets and technical data to match both regulatory changes and evolving user needs. This has saved me and colleagues more than once—especially in collaborative projects where a single outdated parameter could mean running afoul of university protocol or even legal compliance.

What Better Specs and Packaging Make Possible

Many suppliers now offer traceability right to lots and batches. That transparency delivers peace of mind. For anyone scaling up, specifying “anhydrous,” “ultra-high purity,” or requesting a breakdown of potential residuals helps weed out surprises. All these steps echo the priorities laid out in solid chemical practice—clarity, reproducibility, and safety.

One area for improvement in this field lands around access to technical support. Many smaller labs—especially outside of big commercial centers—still struggle to get responsive feedback if specs raise red flags or if they need advice on container compatibility. Direct lines to manufacturer technical staff can cut downtime. Expanded online resources and support would go a long way.

The value of precise purity and the range of available packaging for specialty chemicals isn’t academic. It’s real-world risk management. My experience says the right chemical, in the right package, backed by honest data, saves a project as often as the right idea does.