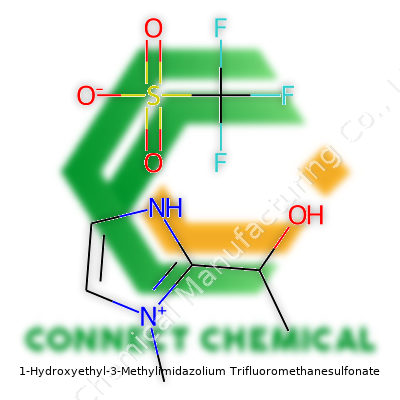

1-Hydroxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate: Unpacking a Modern Ionic Liquid

Historical Development

Chemists started to take a real interest in ionic liquids back in the late twentieth century, but the story of 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate—sometimes called [HEMIM][OTf]—is more recent. The compound grew out of work in the early 2000s, as the green chemistry movement gained traction. Scientists were on the hunt for new solvents that could do the job of old toxic hydrocarbons, without the same risks to health and the environment. Research groups realized that ionic liquids based on imidazolium cores struck a fine balance: stable, tunable, and less likely to evaporate or catch fire than traditional solvents. By tweaking the imidazolium ring with hydroxyethyl and methyl side chains and matching it with trifluoromethanesulfonate (a non-coordinating anion that boosts solubility), labs created a class of ionic liquids that combined power with flexibility.

Product Overview

1-Hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate doesn't look particularly remarkable at a glance. It shows up typically as a colorless to pale yellow, viscous liquid. For years, chemists have reached for this liquid in reaction vials because of its ability to dissolve all sorts of compounds—from transition metals to stubborn inorganic salts. Its unique structure, combining a polar imidazolium ring with a highly soluble triflate anion, gives it an edge in processes where traditional solvents stall. Beneath the surface, this molecule pushes reactions faster, cleaner, and sometimes even safer than the industry standard.

Physical & Chemical Properties

The physical and chemical personality of this compound springs from its molecular makeup. Molten at room temperature, it stays stable over a wide window—up to 250°C for many formulations. Its high polarity and ionic nature lead to low vapor pressure and high thermal stability. Viscosity tends to run higher than common organic solvents, sometimes ten or one hundred times thicker than water, which can be both a blessing and a curse depending on the setup. Water absorbs into it, but not as greedily as traditional salts, which means reactions needing a hint of moisture can usually get by without complete dryness. The triflate anion resists breakdown, so acids and bases can run their course within this solvent without outpacing it.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Packagers tend to sell 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate with purity above 98 percent, targeting applications where trace metal content and water have big consequences on reaction outputs. Labels usually include the CAS number 244102-32-7, batch number for traceability, and relevant purity measurements by NMR or HPLC. Containers need to be tightly sealed since exposure to air doesn’t ruin the substance outright but can let in moisture over time, altering its properties. Safety data sheets highlight its non-flammable nature, but they always urge caution due to the possible long-term health effects of exposure.

Preparation Method

Manufacturers produce this compound through a carefully controlled alkylation reaction. They start by reacting methylimidazole with 2-chloroethanol (which introduces the hydroxyethyl group), then follow with ion exchange using sodium trifluoromethanesulfonate. Mixtures are stirred under inert atmosphere—often nitrogen—and solvents like acetonitrile or methanol let the reaction run efficiently. Crude mixtures get filtered and evaporated, then purified by washing or distillation under reduced pressure. That final evaporation step leaves behind a thick ionic liquid ready for bottling. Each step asks for close monitoring to prevent leftover halides or water, both of which tweak purity.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

What sets this ionic liquid apart is its resilience: it stands up to a battery of organic and inorganic transformations. It doesn’t react directly with most catalysts, and the stable triflate anion shrugs off nucleophilic attacks. Side modifications on the imidazolium ring—swapping out the hydroxyethyl group or the methyl group—give rise to a library of related ionic liquids, each with their own quirks. The current formulation handles everything from metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions to acid-promoted rearrangements. Chemists tinker with it as a reaction medium and sometimes as a stabilizer for oddball intermediates too unstable in other circumstances.

Synonyms & Product Names

In catalogs and papers, 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate appears under several guises: HEMIM OTf, [HEMIM][CF3SO3], and simply imidazolium triflate (although that term technically sweeps up several variants). Some suppliers use product codes, but the right CAS number—244102-32-7—remains the gold standard for certainty in orders.

Safety & Operational Standards

Though it's safer than volatile organic solvents, this ionic liquid warrants respect. It barely evaporates but can cause skin and eye irritation, especially with repeated exposure. Distribution facilities store it in well-sealed, corrosion-resistant containers, away from strong oxidizers. Standard gloves and goggles go a long way, and a well-ventilated fume hood should always be part of the workflow. Waste should be captured and dealt with per hazardous materials protocols: triflate almost never breaks down in the environment, so disposal needs attention to avoid unintended buildup in soil or groundwater. From a workplace perspective, limiting time in direct contact pays dividends in managing long-term risks.

Application Area

Labs and pilot plants draw on this compound in an array of cutting-edge work. Organic chemists count on it for cross-coupling, cyclization, and other complex transformations. In electrochemistry, the wide electrochemical window and high ionic conductivity lift it above traditional solvents for batteries and fuel cells; researchers explore its capacity to carry lithium ions faster, with a lower fire risk than carbonate-based solutions. Industrial players lean on it as a green solvent in biomass processing, dye-sensitized solar cells, and separation membranes. Whenever dissolving power and chemical stability go hand in hand, this molecule finds a role.

Research & Development

Research into 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate marches onward, especially in the quest for sustainable chemistry. Study groups push the boundaries in catalysis, pushing up yields in phosphorus, carbon, and nitrogen coupling processes. Interest in hybrid materials—embedding metal nanoparticles in the ionic liquid matrix for catalytic, optical, or sensing properties—continues to open new areas. Teams at universities and chemical institutes test recycling strategies, aiming to capture and reuse the solvent in multi-step syntheses, which brings real cost savings and reduces waste. The interplay between its solubility profile and reactivity drives ongoing publications, as researchers unlock fresh reaction schemes.

Toxicity Research

Safety lies at the crossroads of innovation and responsibility. Existing animal studies reveal low acute toxicity compared to classic organic solvents, but data on chronic exposures still leaves some questions on the table. The triflate anion resists breakdown, which signals persistence in the environment, and some imidazolium-based liquids have drawn scrutiny for their effects on aquatic ecosystems. Responsible labs treat all new ionic liquids as potential hazards until proven otherwise. Long-term monitoring, better life-cycle analysis, and wider transparency in reporting any health effects all contribute to a safer path forward. Open data-sharing between manufacturers, academic labs, and regulatory bodies remains crucial.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, the future of 1-hydroxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoromethanesulfonate depends on two factors—innovation and stewardship. Advances in green chemistry will keep shining a light on places where this compound outperforms legacy solvents. Applications in battery technology and carbon capture look promising, especially as companies tackle scaling challenges. Ongoing work aims to tweak the structure for even lower toxicity and improved environmental profiles without sacrificing performance. With regulatory agencies now paying closer attention to the fate of all new industrial chemicals, only responsible adoption—full safety data, improved recycling, and judicious end-of-life management—will secure its place in future labs and factories. That crossroads between technical progress and environmental caution shapes how emerging materials like this one will leave their mark.

What’s Behind This Ionic Liquid?

It’s a mouthful, sure, but this compound, often called a task-specific ionic liquid, gets plenty of action in labs and production lines. I’ve spent years watching chemical trends come and go, and it’s clear this isn’t just another chemical used for window dressing. This salt remains liquid at room temperature, which sets it apart from the pack. That property means it can dissolve things most regular solvents leave behind, and it usually doesn’t catch on fire or evaporate much.

Making Things Cleaner in Chemical Reactions

A lot of chemists prize 1-Hydroxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate for what it does in organic synthesis. It often acts as a so-called “green solvent.” Picture a world where labs aren’t always splashing traditional solvents around—less waste, safer spills, happier scientists. The low volatility helps keep it in the flask rather than the atmosphere. More than a buzzword, these ionic liquids are helping researchers reduce chemical footprints and tackle tougher synthesis work, such as tricky oxidations and catalysis with transition metals.

Tough Jobs in Electrochemistry

In battery research and electrochemical devices, this compound shows up because of its big, stubborn anion—the triflate. It helps form electrolytes that last longer and keep safe at higher voltages. Old-school electrolytes tend to break down or even catch fire if you push too hard. I’ve seen this ionic liquid sit in coin-cell prototypes and run cyclic voltammetry without throwing unpredictable curves. It’s not quite ready for the gigafactory, but the jump from benchtop to scale-up looks less bumpy than with some of its peers.

Bringing Out the Best in Biomass

One big challenge in renewable fuels and chemicals: breaking down plant material. Lignocellulose, the tough stuff in stalks and sawdust, usually resists most solvents. Here’s where this ionic liquid stands out. It pries apart cellulose and hemicellulose so enzymes and acids can work faster and cleaner. Researchers in biofuel labs rely on its power to help pull sugars free with less mess, using lower temperatures and milder conditions. In real life, anybody who’s tried to make ethanol from corn stover or old switchgrass knows how frustrating gummed-up reactors can be. This ionic liquid brings down costs because it works even when water and industrial feedstocks are far from pure.

Challenges and the Way Forward

Nothing’s perfect. These specialized ionic liquids can get pricy, and getting rid of them after use can make waste-handling tough. Some researchers mix in supporting salts or recycle the liquid, but there’s room for better solutions. I’ve seen startups tinker with “greener” imidazolium cores and ways to recover triflate-based solvents more cheaply. The next step comes from building closed-loop processes that keep these fluids moving from batch to batch without losing performance or racking up bills for waste disposal. Years from now, there’s a good chance this family of chemicals helps open up new frontiers in sustainable chemistry, if labs and producers get serious about lifecycle management.

Why Purity Matters Outside the Lab

In the world of chemicals, purity is far more than a checklist number. I remember my early days working in a small lab where we scrounged for supplies and every supplier’s certificate mattered. Purity told us if our process would deliver the results we needed or come up short. A lot of buyers glance at specifications—98%, 99.5%—without thinking about what it truly means for downstream work.

Let’s take sodium hydroxide as an example. The stuff you might buy from a generic supplier often sits at around 96% to 99% purity. Grades with the highest numbers fetch higher prices and wind up in demanding sectors like pharmaceuticals and semiconductors. Big-name processors, the ones whose logos land on products worldwide, don’t gamble with lesser grades. Their reputation and the safety of their products, from cleaning agents to tablets in your medicine cabinet, depend on high-purity ingredients.

What’s Hiding in the Other 1%

Buyers sometimes ask, “What’s in the rest?” That 1%, or even half a percent, carries a lot of weight. Impurities range from trace metals to other salts or moisture. In bulk work—water treatment plants, large-scale paper production—a few stray ions may not wreck the batch. But put that same contaminated product into pharmaceutical production or an analytical lab, and losses start piling up. A small amount of calcium or iron can set off a chain of quality problems.

My own experience ordering cheaper sources to save money taught me how the impurities show up exactly where you don’t want them. Once, a batch of “technical grade” hydrochloric acid left strange white precipitate in our glassware because it carried too much sulfate contamination. Chasing the source of the problem took longer than buying the proper, higher-purity acid in the first place. That lesson stuck: better to ask for documentation upfront and pay a little more if quality is crucial.

Certifications and Third-Party Assurances

Some companies wave their specification sheets like a badge. But paper isn’t always proof. Verifying with third-party assays or ISO certification gives extra peace of mind. Responsible chemical distributors often publish batch-specific analysis; the best even allow full traceability, so you know exactly what’s in your drum or tote.

Without that transparency, industries risk product recalls and regulatory problems. A well-known case hit the food industry years back, where substandard ingredients led to product contamination and a wave of recalls. Tightening up transparency from supplier to shipment to lab means better safety for everyone. Modern customers want QR-code access to purity certificates. Some small buyers still get by with word of mouth, but big industry prefers data be available on demand.

Moving Toward Solutions

Manufacturers should invest in more rigorous batch testing and share results openly. Buyers can establish minimum specifications in purchasing contracts and routinely audit suppliers. Building long-term partnerships between buyers and sellers keeps both sides honest and focused on improvement. Strong communication stops costly surprises down the line.

Product purity shapes everything from end-use performance to public health. As digital platforms make it easier to exchange information, everyone gets to benefit—not just the scientists working behind a lab bench. The little numbers on the spec sheet might look dry, but in real terms, they can decide between success and disaster.

Understanding What’s Really Inside the Bottle

Working in a chemistry lab teaches you caution, especially with ionic liquids like 1-Hydroxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoromethanesulfonate. This compound isn’t just another bottle for the bench. Ionic liquids can surprise you if you ignore the details, and this one—commonly used in advanced synthesis and as a solvent—brings unique hazards courtesy of both its imidazolium core and the aggressive triflate anion.

Factoring In Moisture, Air, and Light

Running an experiment gets frustrating quick if your materials degrade before you start. Moisture loves to creep into imidazolium salts, and once it does, purity goes out the window. Chemists run into inconsistent results because humidity slipped in through the cap or because the compound soaked up water off an open benchtop. Keeping this compound in an airtight container (think well-sealed glass, with a reliable gasket) blocks moisture and helps preserve quality.

Oxygen can quietly react with some organic ionic liquids. The safest bet for long-term projects keeps the container under an inert gas like nitrogen or argon, especially if you’re storing large amounts. The extra step saves lost time and wasted material down the line. I remember hunting for the cause of decomposing liquid and realizing it sat next to a window in a warm, humid office. Light plays its own part, sometimes accelerating breakdown. Opaque or amber bottles shelter sensitive compounds from both ambient light and accidental exposure during workday chaos.

Locking Down Temperature and Cleanliness

Temperature swings don’t do anyone favors. This compound prefers a cool, stable spot, away from heat-generating devices or sunny sills. Most researchers launder their ionic liquids in refrigerators set between 2°C and 8°C. Freezers rarely enter the conversation unless a chemical truly benefits, since some salts can crystallize out oddly or separate on thawing. Storing chemicals like these reminds me of that notion: “Tidy lab, tidy results.” Cross-contamination causes headaches. Labels peel; bottles get mixed. Dedicated secondary containment and regular checks guarantee nothing accidentally drips down shelves or mixes into the wrong family.

If someone’s moving the material between storage and fume hoods, every spill or transfer should use gloves and goggles. Triflate-based solvents resist degradation but show their toxicity in subtle ways, so careless splashes or residue can build up on hands and bench tops. I’ve seen new students tempted to skip double gloves “just this once,” only to regret the shortcut later.

Fire and Emergency Pointers Many Skip

No lab should downplay fire risk. Trifluoromethanesulfonate salts rarely catch fire on their own, but mixed with the wrong organic vapor or spill into the wrong waste, the results escalate fast. Keep small amounts on the bench; tuck reserves into flame-resistant varieties of chemical cabinets. Review SDS sheets regularly—every bottle comes with handling and spill information most people never read until something goes wrong. I’ve worked through minor spills by being ready with proper neutralizing agents and pads, practiced not just preached.

Real-World Solutions for Everyday Storage

Follow best practices even after years in the same lab. Keep the bottle tightly closed, away from bright sunlight, in a dry and cool place. Use clear, up-to-code labels showing date of receipt and opening—expiration sneaks up if you don’t track it. Double-check shelf life during each setup. If in doubt, run a purity check or talk with the supplier before trusting old stock.

Respecting chemical storage pays off in real safety and fewer failed runs. That confidence in your materials shows through in accurate, reproducible results—and it keeps the lab drama where it belongs, in memories, not reality.

Real Hazards Lurk in Familiar Places

A lot of folks see a new chemical label and their eyes gloss over the warnings. I’ve been there on job sites, labs, and dusty old garages, hearing someone mutter, "It’s just a little powder, caustic, sure, but it’ll be fine." Problems creep in once complacency sets up shop. Small mistakes—wet gloves, an accidental splash, a quick sniff—can spiral into ER visits faster than you’d expect. Even compounds used for routine cleaning or gardening sometimes pack enough punch to burn skin, aggravate asthma, or corrode tools. Sometimes the risks aren’t obvious. Strong solvents and acids can cut through more than just grime; a careless pour can eat through clothes, leave blisters, or start a chemical reaction that’s hard to stop.

Hidden Dangers: What You Don’t See Can Hurt You

Many compounds look safe. They come in shiny bottles with picture-perfect instructions. Often, they don’t carry a skull-and-crossbones, so folks underestimate their power. Yet, the true risk lives in the dust, the fumes, and the residue left behind after mixing or application. That smell people say is “barely noticeable” is often volatile organic compounds (VOCs) leaking out. Over time, exposure leads to headaches, chronic coughing, or even lung problems. The dust from crystalline materials, often ignored, can settle deep in your lungs and stay there for years, working quietly on your health. Regular exposure, especially for those working daily with certain compounds, brings on real respiratory issues. Skin contact leaves invisible scars, too—sensitivities that build up and turn a mild rash into a dangerous allergy.

What Experience Teaches

After a couple of decades under the hood and in the workshop, you learn where corners get cut. Folks want to save a minute by not bothering with eye protection. Gloves get skipped, especially when the task “looks easy.” A lot depends on reminders that chemicals rarely forgive mistakes. My own knuckles have seen more burns from acid and base than I’d like to admit. Lessons hurt less if you pick them up from someone else’s stories. Once, a coworker mixed a cleaning agent with a simple degreaser and ended up creating toxic fumes. We learned quick that even “safe” products can turn dangerous with the wrong combination. Manufacturers sometimes bury important details, so reading the small print on safety data sheets (SDS) becomes a daily habit.

Simple Steps Make the Difference

Respect for chemical safety doesn’t require fancy gear or expensive training. It takes a real commitment to reading instructions, wearing basic protection—like goggles, gloves, and masks—and keeping workspaces well ventilated. Spills get cleaned immediately, containers get labeled, and no one stores chemicals next to food or drink. Families who keep cleaners in a locked spot up high sidestep trouble. Workers in labs and shops look out for each other—regular checks on storage conditions, good ventilation, clear labeling, and hands washed before touching anything else.

Smarter Choices and the Bigger Picture

There’s no end to creative solutions if you care enough. Safer alternatives have made big strides. Water-based cleaners knock out a lot of the fumes. Pre-measured packets reduce spills and accidental overdosing. Technology now flags exposure in real time, helping folks fix issues before they snowball. No system works perfectly, but a community that shares good practices and honest mistakes can push fatal accidents further out of reach. The best safety gear sits between your ears—talk about mistakes, double-check the label, and never, ever shrug off the gear.

Why Compatibility Really Matters

Working day in and day out with new chemical systems, one thing stares anyone in the face: will this ionic liquid play well with others? If someone skips that question, unpleasant surprises show up fast. The world of ionic liquids has exploded in the last decade, with hundreds finding their way from academic papers to actual chemical processes. Too many labs have watched a promising project stall just because the ionic liquid refuses to mix, instead separating or fouling things up. Sometimes, the answer seems simple on paper — if the ionic and solvent molecules look similar, compatibility must follow. But chemistry refuses to play that game so neatly.

A Lot More Than Just Solubility

Easy mixing, clear solutions, no precipitation: these sound great, but surface appearance won’t tell the full story. Dive a little deeper. Miscibility feels like a checkpoint, not a finish line. Take an ionic liquid that dissolves beautifully in dimethyl sulfoxide. Once a polymer enters the mix, you might see everything cloud up in seconds. At the bench, seeing a blend turn milky never feels good. Now, you end up back to square one — separating phases, recovering materials, and explaining lost time to management.

Where Things Go Wrong: Charge Interactions and Size

Every chemist who’s tried to tune an ionic liquid for a special project knows the pain of mismatched ion sizes. The wrong pairing, and van der Waals forces win out, making the blend unstable. Electrostatic repulsion can break up a solution before it even has a chance. Polarity differences create invisible walls between the liquid and stubborn polymer chains. Add a polar solvent, and suddenly everything behaves differently again. Some of the biggest headaches come from blends that look perfect at room temperature but separate when things heat up during a reaction, or after sitting on the shelf overnight.

Reading the Literature Doesn't Replace Real Testing

Plenty of databases claim to rank “good” and “bad” solvent combinations for new ionic liquids — but real-world performance depends on factors those charts miss. Aging, exposure to light, and plain old batch-to-batch variations all trip up “ideal” systems. Solutions that pass an initial mix may break down after a few days inside a process vessel. Polymer chemistry throws an extra wrench: chains twist, coil, and trap micro-droplets, so testing needs to go well past clear/opaque observations.

Facts on the Table: What Really Works

A few ionic liquids, such as those based on imidazolium with short alkyl side chains, mix reliably with polar solvents like water and acetonitrile. Push those alkyl chains longer and hydrophobic exclusions start to dominate. In work with methyl cellulose and other biopolymers, adding just a splash of the wrong solvent caused brittle solids instead of smooth gels. Patents on ionic liquids for battery electrolytes share endless test graphs — nobody gets trusted on faith alone.

Thermodynamic data helps but looking at viscosity, density, or the simplest “shake flask” experiment has saved plenty of time over chasing theoretical predictions. Collaborating with polymer scientists also adds a reality check: they flag what truly matters on the shop floor, like handling and clean-up hazards, rather than just lab solubility notes or marketing blurbs.

Staying Ahead: Smarter Solutions and Honest Trials

The right answer never comes from paperwork alone. Getting to know ionic liquids and their “personalities” means running hands-on tests. Blends that promise green chemistry or better performance must answer the basics first: will everything stay together, from prep to application? Taking a cue from those who batch-tested hundreds of polymer-ionic liquid pairs, the message is clear. Predict, yes, but always prove it. And don’t let a few nice results in clean glass stop you from checking what happens once time, temperature, and real storage get involved.