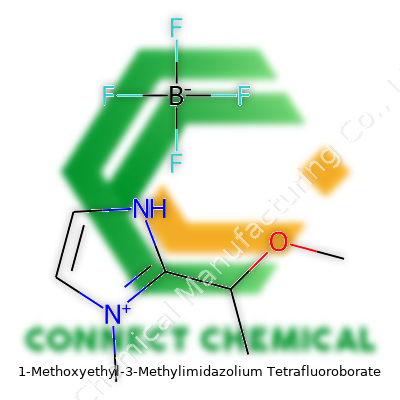

1-Methoxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate: A Close Look at a Modern Ionic Liquid

Historical Development

Ionic liquids once drew only curiosity from a handful of chemists who had the patience to keep track of unwieldy melting points and inconsistent properties. The field picked up steam late in the twentieth century when imidazolium-based compounds delivered stable, tunable fluids that broke some rules of traditional solvents. Fast forward a couple of decades, 1-Methoxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate—known to insiders as [C2OC1mim][BF4]—joined the crowd of these new solvents with a twist: its balance of hydrophobicity, chemical resilience, and ease of synthesis made it a favorite for researchers eager to swap out toxic, volatile chemicals in their labs.

Product Overview

The compound serves as an ionic liquid composed of the bulky, stable 1-methoxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium cation and the trusty tetrafluoroborate anion. Experts appreciate its liquid state at room temperature, its resistance to air and water, and its knack for dissolving more than its fair share of solutes—classic strengths for anyone synthesizing organometallic complexes or running electrochemical tests. Folks dealing with green chemistry spot this liquid as a drop-in alternative to more caustic stuff, streamlining not just benchwork but waste collection as well.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Pale yellow or colorless, with low volatility and almost no noticeable odor, this ionic liquid holds up under heat: thermal decomposition kicks in above 300°C in an inert environment. Viscosity trends run moderate, so solutions don’t gum up valves or glassware as easily as some rivals. Water? The tetrafluoroborate provides a moderate moisture tolerance, but the 1-methoxyethyl group tugs the liquid’s character slightly toward being amphiphilic, letting it dissolve both polar and nonpolar guests with skill. A conductivity score above 10 mS/cm stands out, proving useful in applied electrochemical setups and giving batteries or sensors a boost in performance.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

This ionic liquid often appears in glass-sealed ampoules or amber bottles, typically labeled with purity, moisture content, and CAS number. Users expect technical sheets to provide specific gravity (usually around 1.18–1.22), broad UV stability, and density suitable for scaling syntheses. The best suppliers guarantee water content below 1% and test every lot for trace metal contamination—a nod to those running sensitive catalyses or chemical separations.

Preparation Method

Lab protocols often start with methylimidazole and 1-methoxyethyl chloride, using simple alkylation in dry solvent. Careful temperature control and stirring give the desired imidazolium salt, which reacts next with tetrafluoroborate salts—frequently sodium or potassium sources, since these are cheap and easy to handle. Washing with nonpolar solvents like ethyl acetate, and final drying under vacuum, ensure a clean product, free of halide contamination and excess reagents. Well-practiced chemists clear away byproducts by measuring conductivity and checking NMR spectra for remaining chloride or alcohol groups.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

As an ionic liquid, this compound partners well in transition metal-catalyzed transformations, including Suzuki or Heck reactions. Its imidazolium ring tolerates a wide range of modifications—sometimes incorporating different alkoxy chains or alternative anions like PF6-. The tetrafluoroborate does break down in strong acid or at high heat, so those planning to ramp up reactivity have to choose catalysts and co-solvents with care. Functionalizing the cation opens new doors: swapping the methoxyethyl group shifts polarity, and new anions can boost conductivity or environmental compatibility depending on downstream uses.

Synonyms & Product Names

1-Methoxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate answers to several shorthand labels. Chemical catalogs often abbreviate it as [C2OC1mim][BF4], while older literature sometimes calls it 1-(2-methoxyethyl)-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate. Trade names rarely stray from these standards, keeping communication clear across labs using English, German, or Mandarin.

Safety & Operational Standards

Working with imidazolium-based ionic liquids means keeping an eye on skin and eye contact; they’re less volatile and combustible than their molecular cousins, but direct exposure may still irritate. Most routines demand goggles, gloves, and well-ventilated hoods. National safety data sheets usually flag possible chronic exposure risks, not because acute toxicity looms large, but since decades of hands-on use remain pretty sparse in the record books. Waste collection skips the organic solvent drum: these materials fall under non-halogenated organic waste, though labs tracking persistent pollutants opt for special neutralization or incineration instead.

Application Area

A big chunk of research taps this compound for green solvents—making cellulose dissolve, designing novel electrolytes for lithium batteries, or screening for efficient reaction media in pharmaceutical development. Teams working on CO₂ capture and conversion note its capture efficiency outpaces conventional amines, in part because of the liquid’s ability to form reversible complexes and withstand repeated cycling. Other groups load it into sensors or fuel cells, counting on its robust conductivity and low flammability to avoid the pitfalls of older organic electrolytes. The field also sees this ionic liquid supporting enzyme reactions by stabilizing proteins against denaturation, sometimes outperforming water as a supportive matrix.

Research & Development

Development work focuses on broadening the solvent window and boosting chemical stability. Consortia in the EU and China run parallel research lines scaling up production in greener ways—renewable starting materials, less energy-intensive syntheses, and recycling spent ionic liquids from real industrial processes. Every year, new research emerges on task-specific modifications: attaching catalytic groups, tuning hydrophobicity, or pairing custom anions for targeted separations. The literature reflects open sharing across scientific conferences, with reproducibility taking priority for synthetic advances and real-world pilot projects.

Toxicity Research

Short-term exposure studies on 1-Methoxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate point toward low acute toxicity for mammals and aquatic species at laboratory concentrations. Long-term effects draw less certainty; the imidazolium skeleton persists much longer than many traditional solvents, raising worries about persistence and potential bioaccumulation. Researchers use standardized OECD protocols to assess biodegradability and impact on microbial activity. Some short-term studies show that most ionic liquids, including this one, tend to resist rapid breakdown, but the methoxyethyl group sometimes aids microbial attack, nudging the compound toward safer environmental profiles. Regulatory bodies remain cautious, asking for continuous data, especially if its use expands beyond research and chemical processing into broader commercial or consumer settings.

Future Prospects

The appetite for ionic liquids in green chemistry keeps growing, and 1-Methoxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate stands ready for a bigger stage. As industries chase more sustainable ways to process biomass, recycle metals, or design safer batteries, this compound already checks many boxes: chemical resilience, task-tunable solvency, and less reliance on petroleum. A growing number of academic and industry groups pitch new applications each year, from removing stubborn organics in water treatment to making concentrated gases behave under mild conditions. Regulatory scrutiny and cost pressures push continuous innovation, so smarter preparation techniques and new combinations with other ionic liquids will steer its use further afield, driven by strong research and evidence-based safety standards.

A Chemistry Tool That Earns Its Place

Walking through a modern chemistry lab, you can’t miss the excitement around ionic liquids like 1-Methoxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate. Chemists value this compound for reasons that keep labs running cleaner, safer, and, most importantly, smarter. There’s good reason research and industry both rely on it for more than just traditional solvent tasks.

Shifting the Game in Green Chemistry

Years ago, working with volatile organic solvents ruined both my patience and plenty of glassware. Ionic liquids stopped a lot of that. This compound carries low vapor pressure, so evaporation and hazardous fumes don’t ruin the workday. Because it doesn’t light up easily, the fire risk stays low. Safety managers aren’t chasing down spills that smell up the whole building. For scientists who look for sustainable processes, switching to this ionic liquid means fewer headaches around disposal and environmental impact.

Better Electrochemistry and Energy Storage

Electrochemistry used to mean lots of trial and error with electrolytes. 1-Methoxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate changes that equation. Toss it into lithium-ion battery research, and researchers find improvements in ionic conductivity. Also, devices handle higher temperatures without losing performance. Supercapacitors and fuel cells become more practical with this ionic liquid holding the charge, boosting stability by cutting down on moisture sensitivity and side reactions.

Solvent Uses that Spark Innovation

This compound didn’t just find a home in one or two corners of science. Organic synthesis benefits from its ability to dissolve both polar and nonpolar compounds—something most solvents don’t do well. Transition-metal-catalyzed reactions seem less fussy in its presence. Several times, research partners celebrated higher yields and cleaner extraction steps using this medium. It behaves like a trusted colleague, supporting new methods for pharmaceuticals and advanced materials.

Industrial Separation and Purification

Separating valuable chemicals usually gets messy with water or harsh solvents. Applied in extraction and purification, this ionic liquid steps in with selectivity for metals and organic molecules. Hydrometallurgical processes, like those vital for recycling rare earths, benefit from high efficiency and fewer waste streams. I’ve watched colleagues in environmental industries rely on it to recover heavy metals from wastewater, making treatments both smarter and less polluting.

Potential and Cautions

1-Methoxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate unlocks new pathways for clean tech, but it’s not a magic answer. Some labs see cost as a hurdle for scaling up. There’s also a need for clear data about its toxicity and full environmental effects before industry goes all-in. Regulatory agencies want more information before giving a green flag for widespread use. Collaboration between scientists, safety experts, and industry decision-makers creates better answers for these open questions.

A Path Forward

Industry turns to 1-Methoxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate because it gets work done more safely and efficiently. New applications in catalysis, battery research, and pollution control keep growing as more people recognize its value. Testing, transparency, and a drive to use smarter solvents can open up a new era of cleaner, more responsible chemistry.

Understanding What Puts Chemicals at Risk

Every chemical brings its quirks, and ignoring them can cost you time and money. Some powders lose activity if the air gets too humid in the warehouse. Liquids can turn cloudy or give off odd smells once light creeps in. If you run a lab or work with chemicals for manufacturing, you learn fast: the label’s advice isn’t just legal CYA, it’s how you keep your reputation. I’ve seen a shipment sit near a window for a weekend, and by Monday morning, half of it was worthless because someone assumed the package’s outer box was enough protection.

Temperature: Not Just a Suggestion

Temperature swings ruin a lot of good research. I once worked with a reagent that everyone knew worked best cold. Still, the storeroom ran hot during the summer. After a week, the stuff barely reacted — the lab burned through the project budget buying more. Studies show certain drugs lose half their power just by spending a few days above 25°C. Keeping sensitive material below 8°C is a pain, but freezers and fridges are a must for more than just vaccines. Ice packs in shipments matter every bit as much in biotech as in gourmet food delivery.

Moisture: The Silent Saboteur

Moisture changes everything. Powders clump. Solids turn sticky. Hydroscopic chemicals, such as sodium hydroxide, draw in water straight from the air. Open a bottle carelessly, and the next person to use it ends up with soup, not powder. A cheap silica gel pack tossed inside the storage container can keep a bottle dry for months. Sealing containers tight and keeping warehouse humidity below 40% stops most trouble before it starts. The consequences of giving moisture an opening run from ruined experiments to outright safety hazards.

Light: The Overlooked Enemy

Some chemicals react just by sitting under fluorescent lamps. I remember a dye left by a sunny window for an entire afternoon — faded enough that a whole batch went wrong. Amber glass bottles save the day for most light-sensitive materials. Even cheap aluminum foil can block light if you run out of dark storage space. Not all products need this level of caution, but for those that do, skipping it means your results can’t be trusted.

Air and Oxygen: Not Always Your Friend

Oxygen isn’t always harmless. Some chemicals, especially with metal ions or organics, lose potency just by catching a whiff of fresh air. I’ve known labs who swap out air for nitrogen or argon in special cabinets. Each extra step adds work but pays off in fewer failures. For folks in bulk handling, vacuum-sealed bags and sturdy gasket caps can make a big difference. Even a bit of parafilm around the lid buys you time.

Keeping Records and Sharing Knowledge

Storage logbooks and batch tracking have saved me more times than I’d like to admit. Noting who opened each bottle, what the humidity and temperature looked like, and any odd smells or clumping gives teams a running start if things go sideways. Big firms add barcode tracking. Smaller groups rely on sharp eyes and common sense. For both, sharing lessons learned in real-time keeps everyone on the right side of safety and the profit line.

Solutions Start with Awareness

Investing in simple solutions — basic climate controls, blackout curtains, airtight jars — saves more in lost product than it costs up front. The science backs this up. Staff who learn these rules, not just read them, turn a risky stockroom into a reliable supply chain. Protect the chemical. Protect the work. The rest tends to follow.

Getting Real About Chemical Safety

1-Methoxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, or [MOEMIM][BF4], shows up a lot in labs working on green chemistry and advanced solvents. The rise of ionic liquids like this one gets a lot of scientists excited. They don’t evaporate like old-school solvents and promise cleaner methods in synthetic chemistry. But just because something carries a “greener” reputation doesn’t mean you can skip the gloves and fume hood.

An Honest Look at Hazards

Safety data on newer ionic liquids sometimes feels thin compared to classic solvents like ether or toluene. MOEMIM BF4 slides under the radar in public toxicity databases, yet we know enough about its imidazolium base and tetrafluoroborate anion to read between the lines.

Imidazolium salts, while less volatile, can irritate skin, eyes, and lungs. Researchers who accidentally spill or splash these onto themselves report burning and redness. If you’ve ever worked with alkyl imidazoliums, you’ve probably noticed they feel “slippery” but any contact leaves a stinging tingle. I never touch them without proper nitrile gloves and always clean up spills fast. Tetrafluoroborate can degrade, especially around water or acids, freeing up toxic fumes like hydrogen fluoride. HF, even in low concentrations, attacks tissue and poses a genuine hazard if inhaled or splashed.

Facts From Recent Literature

A number of 2023 studies demonstrate moderate toxicity in aquatic organisms. In one study, MOEMIM BF4 showed inhibition of microbial cultures at concentrations above 100 mg/L. Fish and water flea tests registered negative effects above 50 mg/L. That suggests disposal down the drain isn't just a regulatory misstep—it’s reckless. Chronic exposure in rodents caused mild liver toxicity and changes in blood chemistry over a multi-week span.

Now, this doesn’t mean the stuff will poison you instantly. What it means is that cumulative exposure, especially in poorly ventilated labs, could be more dangerous than people expect. Every bottle I've handled arrives with a GHS exclamation mark and the standard warnings about avoiding contact and inhalation.

What Responsible Work Looks Like

In my experience, hazard isn’t just theoretical. Colleagues once ignored a tiny spill and smelled a faint acrid odor—nobody thought much of it. Hours later, a few started coughing and developed mild skin rashes. Small mistakes around ionic liquids add up fast.

Personal protective equipment matters: gloves, goggles, long sleeves, and solid ventilation. I always use a chemical fume hood, and I keep calcium gluconate gel nearby in case of accidental skin contact with any fluorinated chemicals. Training new lab members on the real risk, not just the written protocol, makes a difference. I also advocate for more thorough hazard reviews: ask the manufacturer for detailed toxicity data, not just what’s on a safety sheet.

Smarter Practices, Healthier Outcomes

Education beats fear. Treating every new or “green” chemical as a potential irritant or toxin protects your health and the environment. Sustainable chemistry succeeds when safety grows alongside innovation. MOEMIM BF4 solves tough lab problems, but only safe habits keep progress from backfiring.

Purity Grades Matter More Than Most People Think

Almost every step in a laboratory or manufacturing environment asks for attention to purity. From years of tinkering with various reagents in research labs, I’ve seen firsthand how lower purity materials can sabotage an entire project. Even trace contaminants have a way of introducing error or dangerous byproducts, and fixing those mistakes often takes more time than just starting over with the right product from the beginning.

Purity grades usually come in a few main types. Technical grade sits on the lower end, mostly for industrial or cleaning processes where small impurities don’t threaten the result. Lab grade lands a little higher, making it good for educational or routine lab work but not suitable for sensitive research. Analytical grade and reagent grade markers signal higher quality—good enough for most chemical analyses and syntheses. At the very top sits ACS grade or ultrapure, essential for specialized instruments, pharmaceutical production, or any situation where even a whisper of contamination could ruin everything.

Environments Dictate the Right Choice

It helps to think practically about what the work calls for. A factory blending cleaner doesn’t need top-end purity—what matters is cost savings without introducing toxins. Anyone synthesizing a pharmaceutical ingredient or running diagnostic tests can’t take those shortcuts. One time I used lab grade sodium chloride instead of ACS grade for a high-precision experiment. My chromatography results came out fuzzy; I later traced the trouble to a tiny amount of something else that crept along with the salt. Quality control labs, especially in regulated industries, often need certificates and documentation showing consistent purity lot-to-lot. Skipping that verification can bring whole batches under suspicion, triggering expensive recalls or safety investigations.

Packaging Sizes Reflect Real-World Needs

Suppliers try to accommodate a range of customers, so the same chemical turns up in lots of container sizes. Smaller bottles—around 100 grams or 250 milliliters—are common for high-purity or expensive materials, allowing research teams to save money and storage space. Labs with more frequent use turn to 500-gram or liter containers. Industrial clients order drum-sized quantities, sometimes 25 kilograms or even 200 liters at a time, buying in bulk to keep production flowing.

My own ordering mistakes taught me that picking the right size avoids both waste and risk. One time I bought a 5-kg drum of a solvent to save on bulk pricing, only to realize we’d never use it all before the expiration date. On another occasion, colleagues ran experiments using material that sat around in opened containers for too long, picking up moisture and losing effectiveness. It’s best to match usage rate with container size, taking into account shelf life and storage limits.

Staying Safe and Saving Money

Certification, labeling, and traceability matter most for regulated products or high-stakes applications. Picking the right grade and size comes down to weighing how much risk the application can handle. Checking documentation and consulting supplier expertise pays off. Students and small labs do best with smaller packages and perhaps a lab or technical grade, as long as purity matches their experiments. Facilities handling sensitive processes or producing goods for market should always lean toward better documentation and higher grade, with appropriate packaging to keep quality stable over time.

Looking Beyond the Hype

I’ve come across a fair share of new products claiming to be game-changers in the world of ionic liquids. Anyone working in electrochemical systems or catalysis can recall ambitions cropping up every year—promise in a bottle, waiting for trial. People ask, will this product deliver something different? Without question, there's excitement about unlocking unique reactivity, better stability, or safer handling. Sorting marketing buzz from genuine advancement—this remains the challenge.

The Details Matter

If I’m assessing a substance for use as an ionic liquid, real performance starts with the basics: actual ionic conductivity, electrochemical windows, and chemical stability. Some of the supposed “ionic liquids” fold under scrutiny, breaking down under mild voltage or temperatures. Classic research flagged early pitfalls, like trace water ripping apart supposedly non-volatile systems. Stability in a glovebox doesn’t always carry over to bench-scale reactors or larger cells. Rigorous purity measures, and reporting all impurities, shape reliable results.

Electrochemical Performance Counts

Experienced electrochemists test multiple cycles before declaring a winner. In my personal attempts, some novel ionic liquids showed promising conductivity but failed to support redox reactions after repeated sweeps. A high-profile paper on pyrrolidinium-based salts comes to mind; plenty of conductivity, not enough tolerance to strong electrochemical fields. Just because something looks good in a test tube doesn’t mean I’d trust it in a lithium battery or fuel-cell stack.

Let’s face it, predictability in a lab doesn’t always scale to pilot plants or industry. Being able to repeat results across labs sets the foundation for trust in new ionic liquids. Established benchmarks—like the iconic imidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide—provide reference points, but useful claims need direct side-by-side comparisons under identical conditions.

Catalysis: Reactivity and Recovery

Over the years, catalytic researchers keep pushing soft boundaries—higher yields, shorter cycles, straightforward separation steps. A product with low vapor pressure and chemical resilience might anchor a catalyst system, but the devil is in leaching and ease of separation. In some of my own catalyst recycling projects, products touted as “ionic liquids” proved too expensive to recover or contaminated the product stream. Clear reporting of recovery rates, as well as any loss in activity, avoids headaches down the road.

Some creative teams are using task-specific ionic liquids tailored for enzyme reactions or CO2 capture. These cases show promise, but transition from elegant lab data to cost-effective industrial throughput isn’t overnight. Every chemist learns: what looks robust in a 10 mL vial often runs into trouble with evaporation, ingredient cost, or cleanup in a 10 L reactor.

Safer, Smarter Choices for the Lab and Beyond

Safety standards shape adoption. Ionic liquids commonly get cited for low volatility, but not all are benign or biodegradable. Many carry questionable toxicity profiles or form stubborn emulsions in water treatment systems. In recent years, regulations around workplace safety and end-of-life disposal made me much more cautious about testing experimental liquids that lack toxicology data.

And it’s not just chemists and engineers. Operators, waste handlers, and end-users have to live with these substances. A recent push for greener chemistry rightly calls for open data in material safety sheets, clear labeling, and thorough environmental impact studies. No shortcut replaces rigorous testing and transparency.

Path Forward: Collaboration Over Hype

Development picks up speed when chemists, engineers, and environmental scientists talk openly about both success and failure. Peer-reviewed comparatives, not just splashy press releases, guide meaningful innovation. My experience says that new products succeed when labs and companies share negative data and partner on real-world tests. Until a fresh product runs the gauntlet through conductivity, reactivity, safety, economic, and environmental tests, its place in electrochemistry or catalysis stays open to debate.