1-Methoxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate: A Commentary on an Imidazolium Ionic Liquid

Historical Development

Ionic liquids have changed the way many chemists and engineers approach solvents and catalysts. The story of 1-Methoxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate grew alongside the broader search for alternatives to volatile organic solvents in the late 20th century. A push for greener chemistry led researchers away from traditional hazardous compounds, drawing attention to imidazolium-based salts. By connecting a trifluoroacetate anion to a substituted imidazolium cation, chemists discovered a pathway toward designing highly tunable, low-volatility liquids. This type of molecule illustrates how a focus on safety and sustainability can foster genuine innovation. In university and industrial labs, these compounds gained attention for their thermal stability and manageable viscosity, which matched shifts in both regulation and environmental awareness.

Product Overview

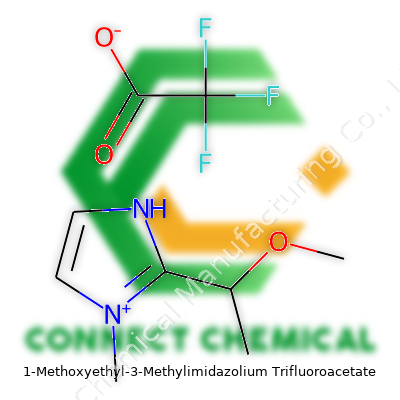

1-Methoxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate belongs to the broad class of room temperature ionic liquids with two distinctive features: a substituted imidazolium ring and a fluorinated carboxylate counterion. Chemists pick it for its unique blend of solubility, low vapor pressure, and the ability to act as a designer solvent. The molecular formula, C9H15F3N2O3, covers the imidazolium core, an added methoxyethyl side chain, and the fluoroacetate group, each part contributing to the balance of polarity, miscibility, and reactivity. Unlike conventional solvents, this ionic liquid demonstrates remarkable resistance to flammability and evaporation, making storage and handling less of a daily headache.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Density and viscosity often hold back the adoption of alternative solvents. Here, 1-Methoxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate shows a relatively moderate viscosity compared to more heavily substituted ionic liquids. Its melting point sits well below room temperature, so it remains in a liquid state at ambient conditions. Being hydrophilic, it mixes with water and polar organic solvents, but the trifluoroacetate counterion also brings a nontrivial chemical reactivity, making it a tool both for extraction and selective catalysis. The imidazolium core supplies thermal resilience, allowing the compound to withstand higher temperatures without breaking down quickly. Its ionic nature also drives low volatility, which lessens inhalation risks and chemical loss due to evaporation.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Suppliers provide this compound as a transparent or slightly yellow liquid, typically packed in sealed glass or PTFE bottles to avoid moisture uptake and contamination. Purity often exceeds 98%, as trace water or halides can influence performance and storage stability. Manufacturers rely on precise labeling for UN numbers, signal words, hazard pictograms, and storage instructions, reflecting its complex nature. Proper documentation supports research integrity and workplace safety. Certificates of Analysis feature NMR, IR, and elemental data to help chemists confirm both identity and purity—a must if reproducibility really matters for a study or scale-up.

Preparation Method

Synthesizing 1-Methoxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate involves alkylating 1-methylimidazole with 2-methoxyethyl chloride under basic conditions, generating the corresponding chloride salt. Subsequent anion exchange with sodium trifluoroacetate, usually in aqueous or polar organic phase, replaces the chloride with trifluoroacetate. Careful purification and solvent removal are needed to achieve the targeted purity and physicochemical profile. Residual reactants or water can complicate product consistency, so chemists watch each step closely, guided by both analytical evidence and practical bench experience. Knowledge of reaction kinetics, crystallization techniques, and washing procedures often separates a clean ionic liquid from a sticky, less effective by-product.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The trifluoroacetate anion opens doors for many applications where acidity and nucleophilicity both come into play. The imidazolium cation can undergo alkylation or functionalization, expanding the molecule’s reach into customized solvent design or ionic catalysis. Many researchers explore how this compound helps solubilize cellulose or fosters selective organic transformations, such as acid-catalyzed condensations. Its unique balance of stability and reactivity also makes it a candidate for immobilizing catalysts or modifying nanomaterials. Anion metathesis remains a powerful tool, allowing easy access to other related salts with different anions and allowing the base structure to evolve as new needs arise.

Synonyms & Product Names

1-Methoxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate pops up under different commercial and IUPAC names: [2-methoxyethylmethylimidazolium][trifluoroacetate], [CMMIm][CF3CO2], or simply as a “fluorinated imidazolium ionic liquid.” Researchers sometimes abbreviate it as [MOE-MIM][TFA] in technical discussions or journal articles, a shorthand that echoes the growing use of imidazolium salts across disciplines. Commercial catalogs feature it under slight variations, underscoring the need for careful identification to avoid mix-ups with similar compounds bearing only minor structural tweaks.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling fluorinated carboxylates comes with particular responsibilities. Some ionic liquids seem benign compared to volatile, flammable solvents, but this one absorbs water from the air and can irritate skin, eyes, and mucous membranes, especially in concentrated or warm environments. Labs make use of gloves, goggles, and efficient fume extraction since accidental contact or mixing can release acidic vapors. Waste collection follows guidelines for halogenated organics. Long-term exposure studies remain limited—it pays to take extra care, practice regular hygiene, and maintain strict records for both storage and disposal.

Application Area

Research groups value 1-Methoxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate in biomass dissolution, particularly for breaking down cellulose and lignin structures. Its high polarity and acidity facilitate the extraction of plant fibers, creating opportunity in sustainable material development. Others use it in pharmaceuticals as a medium for challenging transformations or as a catalyst. More recently, it made inroads in electrochemical applications, such as batteries or capacitors, where ionic transport and stability drive performance. The compound’s solvating ability also breathes new life into certain separation processes, including liquid-liquid extractions where both selectivity and recyclability matter. Its adaptability spurs ongoing interest from green chemistry consortia and technology transfer offices alike.

Research & Development

Innovation efforts circle around improving selectivity, biocompatibility, and recyclability, each a key factor for scaling up from laboratory curiosity to process staple. Synthetic organic chemists keep trying to streamline preparation and purification, since byproducts and residual reagents influence downstream applications. As part of an international move toward less toxic solvents, new data sources inform choices about operating conditions, including water tolerance, thermal stability, and chemical compatibility. Collaborations with environmental scientists and toxicologists aim to map out degradation routes, persistence, and interaction with common substrates. I’ve seen first-hand that universities partner with industry here, not just out of curiosity, but because real economic gains emerge when ionic liquids prove stable, reusable, and greener.

Toxicity Research

Compared to legacy organic solvents, imidazolium ionic liquids look less hazardous in short-term exposure tests. Still, emerging evidence suggests caution—particularly with trifluoroacetate anions, because breakdown can form persistent, bioaccumulative compounds. Biodegradability and chronic toxicity don’t always match desired lab performance, so researchers continuously dig into metabolism, aquatic toxicity, and soil risks. Real progress depends on transparent sharing of negative results as much as on positive headlines. Lessons from earlier solvents, like dichloromethane or benzene, remind chemists that initial promise often falls apart if risk assessment lags behind. Institutions assess long-term toxicity using zebrafish embryos, bacteria, and plant models, and establish clear protocols for tracking emissions along the supply chain. Regulatory agencies expect robust, reproducible studies before green-lighting large-scale adoption.

Future Prospects

Ionic liquids like 1-Methoxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate continue to push chemists to rethink what counts as a green solution. Industrial adoption will hinge on price, production scale, and data from long-term environmental monitoring. A move toward renewable synthesis, including bio-based imidazolium cores or less persistent anions, could take this family of liquids from specialty niches into everyday manufacturing. Tabletop and pilot studies foreshadow wider use in battery electrolytes, biorefineries, and pharmaceutical processes. Policy developments will likely focus on lifecycle analysis and real-world toxicity. Startups, academic labs, and established producers all look for ways to tweak structure–activity relationships to manage risk and boost performance, seeing in this liquid not just another solvent but a platform for broader change in chemistry.

A Peek into the Chemical Backbone

1-Methoxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate isn’t a name you’ll stumble into at the grocery store, but it deserves some attention. Its chemical structure starts with an imidazolium ring. If you picture a five-membered ring with two nitrogen atoms at positions 1 and 3, you’re in the ballpark. Off the first nitrogen, the chemical features a 1-methoxyethyl group—a two-carbon chain with a methoxy group hanging off the first carbon. There’s also a methyl group attached to the nitrogen at position 3. These tweaks give the molecule personality, making it more than just another ion in a bottle.

The positive imidazolium chunk pairs up with trifluoroacetate, an anion with the structure CF3COO-. That’s a little carbon skeleton with three fluorine atoms clustered on one end. These fluorines tug on electrons, making the anion stable and unreactive. For people who deal with ionic liquids, stability like this takes the stress out of the lab.

Why This Chemical Matters

I first encountered ionic liquids like this during some research on alternative solvents. Solubility plays a huge role in chemistry, green manufacturing, and recycling. Traditional solvents can escape into the air, hurt the planet, or catch fire easily. Ionic liquids such as 1-methoxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate bring something new: they barely evaporate, they stay put, and their reactivity can be tailored. That’s no small feat.

With trifluoroacetate as the counterion, this salt tackles pesky organic molecules that shrug off water-based treatments. Think cellulose, stubborn dyes, or old plastics. The strong electron-withdrawing properties of those trifluoromethyl groups tweak acidity and polarity in the liquid, opening up new reaction pathways. In the world of recycling or precision synthesis, that flexibility clears the way for new technology.

Challenges and Room for Growth

Nothing in chemistry comes without problems. Working with ionic liquids means balancing their benefits against cost, toxicity, and long-term environmental impacts. The trifluoroacetate anion shares some of the downsides seen in other fluorine-heavy molecules; they don’t break down easily and can stick around in soil or water longer than we’d like. Research labs and manufacturers should test alternatives and monitor waste streams to keep production sustainable.

From my own experiments, contamination or incomplete purification sometimes throws off anticipated performance. To draw out the best in imidazolium-based liquids, researchers could try new synthesis routes that ditch harmful reagents or pave a shorter path to pure products. Computer modeling helps by predicting how tweaks to the side chains alter physical and chemical stability. Working directly with teams from green chemistry, toxicology, and disposal backgrounds adds another layer of safety and insight.

Paving the Road Ahead

As new industries explore ways to process tough materials or limit solvent footprints, chemicals like 1-methoxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate show up more often in the conversation. Companies and universities should invest in both life-cycle studies and scalable recycling for used ionic liquids. We won’t find all the answers overnight, but paying close attention to structure, impact, and innovation lets these complex molecules live up to their promise instead of just adding to tomorrow’s problems.

Real Workhorse in Chemical Processing

People inside laboratories and factories lean hard on chemicals that can handle tough tasks. 1-Methoxyethyl-3-methylimidazolium trifluoroacetate—let’s call it MEMIM TFA—regularly pops up in research focused on green chemistry and advanced material sciences. Chemists treat this ionic liquid almost like a heavyweight lifter in their toolbox. Its room-temperature liquid state brings some big advantages. For one thing, it won’t burst into flames or evaporate like volatile organic solvents. That’s a good thing if you care about workplace safety and waste. With stricter rules about pollution and exposure, nobody wants to deal with fumes and fire hazards that come with old-fashioned solvents.

Apple of the Eye for Cellulose Dissolution

Anyone who’s worked with plant fibers knows dissolving cellulose isn’t simple. Regular solvents won’t touch it. MEMIM TFA finds a niche as a cellulose solvent. Researchers aiming to develop biodegradable plastics or sustainable textiles choose this chemical to break down tough fibers from wood, cotton, and agricultural waste. After cellulose gets dissolved, it can be re-shaped or spun into new forms. This trick unlocks ways to make high-value products that cut down on plastic pollution and fossil-fuel-based materials. According to reports in Green Chemistry and Carbohydrate Polymers, scientists use ionic liquids like MEMIM TFA to drive breakthroughs in sustainable packaging and specialized films.

Key Player in Synthesis and Catalysis

My own dive into chemical synthesis highlighted how these ionic liquids smooth out tricky reactions. MEMIM TFA stands out because it keeps a steady liquid form even at room temperature, so you don’t need extra heat. It often serves as a reaction medium for organic transformations where water or regular solvents cause trouble. Experts prize its low volatility and non-flammability, especially in pharmaceutical labs where safety and purity stay top priorities. The presence of both the imidazolium and trifluoroacetate parts lets it both dissolve a huge range of compounds and even help coordinate reactions. This helps fine-tune yields and reduce the mess of by-products. That’s the sort of edge that means less waste, greater precision, and fewer headaches with cleanup.

Cleaner Pathways for Extraction Processes

Solvents remain everywhere in chemical extraction, whether for flavors, medicines, or precious metals. MEMIM TFA comes up more often as researchers look for “greener” swap-outs—one of many ionic liquids that avoid the toxic, hazardous side effects of older methods. Environmental Health Perspectives and similar journals have flagged ionic liquids as a realistic bridge between strong performance and lower toxicity for workers and ecosystems alike. Using this chemical, labs can pull target compounds from plants or minerals without dumping hazardous solvent waste down the drain. I’ve seen it used to extract fine chemicals from lavender and rosemary, processes that once called for harsh chemicals.

Challenges and The Road Ahead

No one makes progress without facing a few obstacles. Even though MEMIM TFA offers a safer alternative in many settings, its price tag tends to run high compared to bulk chemicals. Getting a supply at scale takes planning, and recycling the liquid still poses technical problems. As manufacturers eye larger operations, finding systems for recovery and reuse turns into a priority. There’s also the question of long-term toxicity. While it beats many fossil-fuel-based solvents on toxicity, its full environmental profile still needs more honest, open research. Anyone working with new chemistry owes it to the planet to understand not just what the chemical can do, but how it behaves throughout its whole life cycle.

Why Storage Really Matters

Stashing a product onto any old shelf can lead to a host of headaches down the road. Years of working in industries ranging from food to chemicals have taught me that the little things matter the most: temperature swings, damp corners, even direct sunlight creeping across a pallet can change a product’s quality or safety profile. Some will point to rules or charts for guidance, but personal vigilance wins the day. For example, I once saw an entire batch of flour turn clumpy and unusable because it shared warehouse space with a leaking window. The moisture didn't just wreck one bag; it triggered a domino effect—mold, spoilage, financial losses, and, in the worst case, recalls.

Temperature’s Silent Influence

Incorrect temperature can quietly chip away at both effectiveness and safety. In the case of pharmaceuticals or perishable foods, too much heat weakens their strength or speeds up spoilage. One of the most frustrating calls I’ve fielded came from a grocer who struggled with medicine complaints during a summer heatwave. His storeroom thermometer read ten degrees higher than recommended—customers noticed, and word spread fast. The fix? Simple investments in fans, shade, and digital thermometers paid for themselves multiple times over through fewer complaints and better returns.

Keep It Clean, Keep It Dry

Dirt and moisture seem harmless, but they provide breeding grounds for bacteria and pests. I’ve found that quarterly deep cleans and basic pest control stop big problems before they start. Packaging should stay dry and intact. Even small tears in a bag or box open the door to contamination. In one case, a pallet stored near the receiving dock picked up not just dust but rodent droppings—everything had to be discarded. Establishing clear storage zones with physical barriers, like pallets off the ground and away from exterior doors, made a dramatic difference in loss rates, according to a study by the Institute of Food Technologists.

Labeling and First-In, First-Out

Clear, bold labels with expiration dates save headaches—not just for workers, but for management audits. I make a routine of rotating stock every time a new shipment arrives. This “first-in, first-out” habit means older products are distributed before new ones. It sounds basic, but skipping this step happens more than people admit and costs real money. According to the FDA, lack of proper product rotation ranks among the top three causes of recall notices in packaged foods.

Employee Training Makes or Breaks the Process

Workers often juggle many responsibilities. Slowing down to check conditions or read labels sometimes feels like a hassle. Skills stick best through hands-on demonstrations and clear procedures. At one plant, we lost hundreds of hours to retraining after a single spill because no one caught a leaking drum early enough. After that, we put in regular drills and it all changed—for the better.

Solutions That Stick

The best results grow from a mix of simple habits and smart investment. Reliable climate controls, regular maintenance, and clear labeling do far more than just meet guidelines. Preventing loss or contamination isn’t glamorous, but it keeps customers coming back and authorities off your back. Over the years, I’ve learned that the companies with the best records handle every box with the same care as the first one off the truck. Every dollar spent on prevention beats ten lost fixing avoidable mistakes.

Looking Past the Chemical Name

Names like 1-Methoxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate sound intimidating. To people in labs or industrial spaces, these ionic liquids show up as the latest in green chemistry. Big promises usually tag along—better solvents, cleaner reactions, sometimes easier separation. Marketing aside, every compound deserves a hard look at its downsides, including health risks and environmental impact. Experience in chemical research taught me to hesitate before trusting claims about “safer” reagents. New chemicals often outpace the toxicology studies and, by extension, clear workplace safety guidelines.

Digging Into Known Data

For 1-Methoxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate, detailed public studies sit in short supply. Ionic liquids based on imidazolium have been around for a few decades, increasingly in use for extractions, catalysis, and electrochemistry. The allure comes from their low vapor pressure—less risk for inhalation compared to volatile solvents like ether or benzene. Lower volatility cannot distract from other risks. These compounds still make skin and eye contact risky, and spills leave cleanup burdens behind.

Researchers already pointed out that many imidazolium-based ionic liquids disrupt aquatic life at pretty low concentrations. Certain species struggle to survive even in trace amounts. It can be tough to break these molecules down, so anything released into water or soil lingers—possibly for years. Add in the trifluoroacetate part: Fluorinated compounds often stick around, resisting microbial breakdown and sometimes moving up food chains. Even if this specific combination hasn’t triggered an environmental scandal yet, history with similar substances gives clear warning signals.

Understanding Health Effects

There’s little sense in taking chances. Most imidazolium ionic liquids bother the skin and eyes, triggering irritation or even burns with enough contact. Some break down into methylimidazole under certain conditions, and that byproduct causes its own problems. Trifluoroacetate can act as a metabolic disruptor in some organisms. Labs handling this stuff usually warn staff to work behind fume hoods, double up on gloves, and prevent any spills. Without solid long-term toxicology studies, only assumptions exist about cancer risk or systemic damage from repeated exposure.

Regulatory bodies lag behind because compounds like these stay niche for now. Judging by workplace requirements around similar ionic liquids, basic protection feels non-negotiable: eye protection, nitrile gloves, and full skin coverage. Ventilation cuts down any risk from accidental heating or splashing. Disposal never fits standard systems—these chemicals count as hazardous waste, and pouring anything down regular drains means pollution, plain and simple.

Building Safer Practices and Greater Transparency

Precaution feels smarter than regret, especially in a world where new chemicals keep appearing faster than the studies do. Researchers and companies should demand open data on toxicology and environmental fate before new ionic liquids see wide use. Any step skipped today risks worker safety and can sow the seeds for tomorrow’s environmental headaches. Chemical innovation has real value, but it loses meaning if it creates new hazards behind the scenes.

Until independent studies give a green light, users of 1-Methoxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate have every reason to treat it as hazardous—using every layer of protective gear and training possible, and always handling waste like it can cause harm. No compound’s convenience beats real caution.

Staring Down the Facts in the Bottle

I’ve spent plenty of time pacing back and forth in a lab, watching colleagues debate whether our chemical supplier’s certificate of analysis means anything tangible. Purity isn’t just a bragging point whispered in a catalog; it's the promise that what’s inside your flask performs just the way you hope. For 1-Methoxyethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Trifluoroacetate—sometimes called MOEMIM TFA for short–purity means the difference between a chemical that supports clear scientific results and one that clouds the whole process.

Real Numbers Instead of Speculation

Commercially available MOEMIM TFA most often carries a listed purity between 95% and 99%. I’ve seen trusted catalogs like Sigma-Aldrich or Acros Organics put theirs at 98% or higher. This level doesn’t come as a surprise in academic labs hoping to avoid fluke results or wasted research hours. In industry labs, anything less rarely lands on the shelf unless the budget leaves no other option.

The natural question kicks in—why not push for 99.99% every single time? The answer ties to the production and purification steps. Trifluoroacetate salts attract water and odd impurities during synthesis and handling. Drying them past 98% demands time, vacuum work, and more resources than some uses can justify. If you just need a solvent for a test reaction, 95% sometimes clears the bar at a lower price.

The Gritty Side of Purity

In my own work, running ionic liquid synthesis in glassware that always seems to develop a chip, I’ve watched the headaches cause by "trace" contaminants. Those last few percent aren’t just numbers—they mean lithium leaching from an impure stirring rod or some lingering solvent sneaking past a too-quick distillation. Ionic liquids like MOEMIM TFA draw water from air almost as fast as you can turn off a desiccator. Picking 98% over 95% can shrink wildcards, but the shelf environment also plays its tricks. Real-world purity lies not just on the label but in how you store and handle the stuff.

Certificate data usually lists water by Karl Fischer titration, along with halide, heavy metals, and residual starting materials like 1-methylimidazole or trifluoroacetic acid. Actual measured water content can swing from below 0.5% in the best-stored lots, up towards 2% in poorly handled ones. Each percentage point alters reactivity, especially in moisture-sensitive processes—like catalysis or battery electrolyte studies—where even a hint of water can throw months of planning sideways.

The Path to Reliable Results

Focusing on trustworthy supply chains and sporadic third-party testing pays for itself. Every technician I know who’s run a failed batch because of off-spec reagent learns this lesson once, sometimes the hard way. Asking suppliers for lots with full impurity profiling, instead of just total organic content, matters more than many believe. Refrigeration, desiccation, and prompt use after opening knock out the sneaky purity drops that can sabotage a project.

Peer-reviewed data backs up a simple point: the closer you draw to 99% purity in MOEMIM TFA, the more reproducible your chemistry gets. In sensitive applications, the upfront effort secures safety and scientific integrity. For the high-stakes or high-cost situations, penny-pinching on purity rarely works out over the long run. Every small impurity brings a chance at failure or faulty data—and that’s not something you want looming over your next publication or product run.