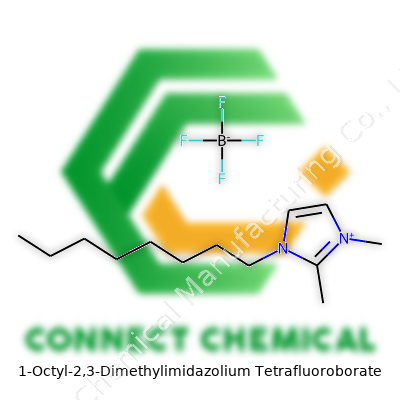

1-Octyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate: A Deep Dive

Historical Development

Decades ago, researchers in green chemistry circles began chasing after ionic liquids for their unusual stability and environmental promise. Among the early contenders in this field, 1-Octyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate (ODIM-BF4) came onto the scene as a strong candidate for replacing volatile organic solvents. Labs in Europe and Asia drove much of the initial synthesis work. The field started seeing ionic liquids not only as novel solvents but also as highly tailorable chemical tools. The imidazolium-based ionic liquids, such as ODIM-BF4, found a warm welcome as researchers sought ways to design substances with tunable properties for demanding processes.

Product Overview

ODIM-BF4 is built from an imidazolium ring, substituted with methyl groups on carbons two and three and an octyl chain at position one. The counterion, tetrafluoroborate, grants high solubility and significant electrochemical stability. By adjusting the length of the alkyl chain, chemists aim for an ionic liquid that tackles specific process needs, like dissolving both organic and inorganic materials. The product’s structure supports its use as a solvent, catalyst, and electrolyte across diverse chemical landscapes.

Physical & Chemical Properties

ODIM-BF4 pours out as a colorless or light yellow liquid, resistant to evaporation under normal atmospheric conditions, and refuses to ignite easily, which sidesteps many hazards common in traditional solvents. It clocks in with a density often between 1.1 and 1.2 g/cm³, depending on purity and water content. On the thermal scale, it handles high temperature without breakdown, surviving up past 350°C before serious decomposition sets in. Its low vapor pressure, wide liquid range, and broad electrochemical window give ODIM-BF4 an edge in situations needing solvents that stay put and outlast heat shocks. Conductivity and viscosity hinge on the purity, but most samples allow for moderate ion flow, which matters for electrochemical applications.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Producers label ODIM-BF4 by purity — research work demands levels above 98%, with strict limits on halides and water. Color and appearance offer first hints of quality, and batch sheets call out specific ionic conductivities and trace element readings. Shipping containers usually follow UN packaging guidelines for nonflammable, low-toxicity liquids. Regulatory documents accompany each shipment, mapped to GHS rules, with hazard pictograms mostly absent except for irritant warnings.

Preparation Method

ODIM-BF4 requires a two-step process in most labs. The starting imidazole receives octyl and methyl alkylations in controlled stages, relying on safe bases and dry solvents. The intermediate imidazolium salt forms as a halide and then undergoes anion exchange with sodium or silver tetrafluoroborate. Filtration clears precipitates, followed by careful drying under vacuum to avoid introducing moisture, which can destabilize ionic liquids. Methods continue to improve, reducing waste salts and tuning yields for larger operations.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Chemists work with ODIM-BF4 in several reaction spaces. The imidazolium core can tolerate moderate acid or base, helping catalyze reactions as both phase-transfer agent and reaction medium. It stands up against oxidation better than many organic solvents. Mix it with reactive nucleophiles, it's tough enough to hold form, thanks to the way the borate anion stabilizes the positive charge. Swapping out the octyl chain or methyl positions leads to ionic liquids of different polarity or viscosity, but ODIM-BF4 holds a sweet spot for organic synthesis and electrochemistry work.

Synonyms & Product Names

Across catalogs, ODIM-BF4 goes by several names: 1-Octyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, OMIM-BF4, and CAS references are common. Some suppliers brand it as a specialty electrolyte or designer solvent. Academic papers often shorten the naming to “[OctDMIM][BF4]” for brevity. Names may shift, but the chemical remains trusted in the labs that use it for precise tasks.

Safety & Operational Standards

Even as ODIM-BF4 avoids many of the big dangers of organic solvents, operators should keep skin and eyes away from contact. Repeated handling in poorly ventilated rooms can dry skin or irritate eyes. Waste streams carrying ODIM-BF4 belong in specialized disposal bins and shouldn't mix with strong oxidizers or acids. The chemical resists sudden combustion, though high temperatures in closed systems demand monitoring for pressure buildup. Training workers to handle spills quickly and through standard personal protective gear makes all the difference — nitrile gloves, goggles, and basic lab coats cover all typical risks. Labs using the compound most often run fume hoods for added safety during transfer and reactions.

Application Area

ODIM-BF4 sees the most use in green chemistry, where switching out volatile, poisonous solvents matters immensely. In battery research, the stability and wide voltage window allow for durable, safe electrolytes in next-generation lithium and sodium cells. The compound finds a place in catalysis, helping reactions run faster or at lower temperatures, all while sidestepping emission of harmful fumes. Chemical separations — from rare earth recovery to pharmaceuticals — take advantage of its high selectivity and ability to dissolve targets that resist most solvents. Other researchers drop ODIM-BF4 into sensors and analytical gear, banking on its electrochemical reliability and chemical inertness under many stress tests.

Research & Development

University teams and industrial labs remain busy with ODIM-BF4 modifications, hunting for lower toxicity, better recyclability, and even stronger thermal stability. New work pushes into absorption of greenhouse gases, particularly CO₂, with ionic liquids that grasp pollutant molecules more effectively. Ongoing investigations chart the biological breakdown of ODIM-BF4 and its relatives, informing policies for environmental safety and waste management. As industrial scale-up grows, teams work at cutting costs to open the door to broader market entry.

Toxicity Research

Toxicity studies show that ODIM-BF4, like most ionic liquids, has a mixed profile. Aquatic toxicity comes up as a concern, with high levels threatening local water insects and fish, especially in small or poorly diluted discharge. Chronic exposure in people can cause skin dryness and mild irritation, but lab conditions and safeguards have kept incidents very low. Biodegradation runs slowly, so untreated waste can persist if mishandled. Studies highlight the need for closed-loop recovery and proper disposal, especially as regulatory agencies start including some ionic liquids in watch lists for industrial pollution.

Future Prospects

Growth looks strong as cleaner chemistry options gain ground in industry. Researchers hope to engineer more biodegradable, even smarter variants — ionic liquids that can act as catalysts, absorb pollutants, or tune electronic properties on the fly. ODIM-BF4 stands as a reliable, well-characterized option, trusted by engineers and chemists. If recovery methods and lifecycle management keep improving, expect to see ODIM-BF4 and its cousins leading the charge wherever old solvents fall short or regulations grow tighter.

A New Generation of Solvents

1-Octyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate stands out in labs and industry for its use as an ionic liquid. Ionic liquids didn’t catch much attention outside specialized circles until about two decades ago. Now, they help push the boundaries of what’s possible in chemical reactions, extractions, and electrochemistry. Out on the bench, this compound offers more than a fancy name—it brings real advantages, especially where traditional organic solvents lag behind.

Tackling Impossible Reactions

Researchers value this compound because it serves as a robust medium for reactions that demand both chemical stability and minimal volatility. Run-of-the-mill solvents like acetone or chloroform evaporate fast and create safety headaches. 1-Octyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate hardly evaporates at all at room temperature, which makes it safer for people who use it every day. The tetrafluoroborate anion keeps things stable, so side reactions stay low. That’s important in pharmaceutical labs, where impurities can threaten a whole project.

Powerful Solvent in Green Chemistry

Back in my grad school days, switching from traditional solvents to ionic liquids felt like stepping into a new era. I could run extractions, dissolve tough reactants, and avoid the headaches that come with volatile fumes. This compound, with its bulky imidazolium-based structure, dissolves both polar and non-polar molecules with ease. You can pull out targeted chemicals from mixtures without resorting to petroleum-based solvents, helping green chemistry projects move beyond promises into real progress.

Advantages in Electrochemistry

Energy storage research often deals with safety hazards. Lithium-ion batteries, for example, need safer electrolytes that don’t catch fire or break down easily. 1-Octyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate finds its place here because it stays stable at high voltages and doesn’t catch fire like traditional electrolytes. Electrochemical researchers have used this compound to boost ionic conductivity and switch to non-flammable platforms. It also resists water and doesn’t break down as quickly, letting engineers test new battery designs without worrying as much about breakdowns or toxic byproducts.

Big Picture: Meeting Practical and Environmental Demands

The world doesn’t move forward on hope alone. Chemical industries face tighter rules on emissions, worker safety, and waste. Using compounds like 1-Octyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate keeps them out in front. They can recycle ionic liquids more easily than most solvents, which means less chemical waste in waterways or landfills. Several studies, including work from the University of York and others, show how plants can re-use ionic liquids for multiple cycles without a dip in performance, slashing costs over time.

Challenges and Better Ways to Use It

The story doesn’t end with glowing reviews. One problem is cost. Synthesis and purification of this ionic liquid can set budgets back, especially compared to off-the-shelf solvents. Scaling up production safely also needs care, since the fluorine content must be managed to avoid environmental impact. Researchers look for cheaper raw materials, create cleaner processes, and design recycling methods for these liquids. There’s also a push to understand toxicity. Good lab habits and regular hazard reviews go a long way here.

Wrapping Up: Beyond Lab Curiosity

In my experience and across peer-reviewed studies, 1-Octyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate proves its worth in places where other solvents come up short—boosting yields, keeping people safer, and cutting waste. Researchers keep improving how they synthesize and recycle it, which paves the way for cleaner and more efficient chemical processes worldwide.

Salt: More Than What Fills the Shaker

Anyone who’s baked bread or seasoned a stew knows salt is a kitchen regular. That grit turns up in chemistry class too, under the name sodium chloride, NaCl. While it lands on food by the pinch, it holds a central role in science and industry. My first introduction came during a simple experiment: add some to water, watch it vanish. Right there, you see both a physical and chemical world at play.

What You See, What You Measure

Sodium chloride shows off as colorless, cubed crystals or a white powder. It crunches underfoot and dissolves in rain puddles along city sidewalks. You can spot straight lines in a salt crystal, a reason students latch onto its cubic shape in early science labs. Salt refuses to melt in the average oven, standing strong with a melting point of about 801°C (1,474°F). That number signals it needs hefty heat for a phase change, something not every kitchen encounter will supply. It boils off as vapor at an even higher temperature, about 1,413°C.

Sometimes kids lick a driveway in winter on a dare. They get it instantly: sodium chloride tastes salty, one of the classic flavor triggers for the human tongue. That taste ties to its ionic nature. The compound isn’t going to stink up the room either; it carries no noticeable smell to the nose.

Going Down to the Molecular Level

This humble crystal packs a simple, sturdy structure. Each sodium ion lines up next to a chloride ion, locked in a repeating pattern. This neat arrangement explains a lot. Drop salt into water, and the ions leap apart, each getting tugged by water molecules. That ability to break into ions explains why salt solutions conduct electricity. As a teenager wiring a potato clock, saltwater made the difference between silence and ticking.

It resists catching fire or crumbling from sunlight exposure. It won’t gas off or corrode pipes like some substances, but if it piles up unchecked, it can rust metal and kill garden plants. Those real-world headaches show up every winter from road salting, hinting at the environmental price of convenience.

Real-World Uses and Downsides

Salt’s impressive stability and affordability let it slip into almost every industry. It can help preserve meat, tan leather, flavor chips, clean wounds, and even treat icy sidewalks. Those uses sound positive, but the heavy mining and dumping needed to meet global demand leave scars. Salt mining can ruin landscapes, and over-salting soil pushes farmers and communities to spend more money restoring land for crops.

Communities are starting to look for smarter salt use. Road crews experiment with brine blends and temperature-targeting so they apply less per storm. Some cities invest in salt-tolerant landscaping, while researchers explore alternatives, like beet juice mixtures for de-icing. Households can rethink how much salt they pour onto food or paths outside, taking small steps with large-scale ripple effects. Every time we handle a scoop of the stuff or watch it dissolve, we play our part in this compound’s journey across science, environment, and health.

Getting Familiar with the Chemical

1-Octyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate doesn’t show up at most kitchen tables, but it pulls some weight in research labs. People often call it an “ionic liquid,” which means it’s a salt in liquid form at room temperature. These materials fascinate chemists because they have almost no vapor pressure and won’t just float into the air like regular solvents. This can cut down on air pollution in labs, though it doesn't mean the chemical lives up to the hype as “safe.” Many ionic liquids, especially those containing tetrafluoroborate, have health and environmental risks buried beneath those long, complicated names.

Risks in the Real World

Way back in college, my lab group started experimenting with ionic liquids. These chemicals sounded magical since they don’t burst into flames easily and barely smell at all. Still, we learned fast to treat every new compound with skepticism. Some imidazolium salts can irritate skin and eyes; a careless splash left a friend’s hand red and itchy for hours. Studies show even minor skin exposure may cause a reaction. Inhaling dust or tiny droplets can bother your lungs. Even a few drops left uncleaned can go unnoticed until someone rubs their eye mid-experiment or sneaks a sandwich into the lab, despite every warning poster in sight.

Fire and Chemical Stability

Anyone who reads a chemical’s data sheet looks for fire risk above all else. Now, 1-Octyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate won’t catch fire like gasoline, but heating it up or mixing it with strong acids can cause nasty decomposition fumes. Tetrafluoroborate likes to break down under heat, and that sometimes means toxic boron or fluorine-containing gases. It pays to remember that just because something doesn't explode, doesn't mean it's harmless. I once walked into a lab after a fume hood leaked, and the stinging eyes and sore throat stuck around long after the broken bottle got mopped up.

Protective Gear and Common Sense

Everyone around chemicals should get used to lab coats, gloves, and goggles. If you’re handling this compound, toss nitrile gloves on your hands instead of cheap latex; ionic liquids can eat right through the thin stuff. Always wear eye protection since one bad splash could cause permanent damage. Work in a fume hood, every single time. Trust me, it only takes one strong whiff to remember why these rules exist.

It’s tempting to cut corners during cleanup or late-night experiments. Don’t. Wash any splash from your skin right away, and keep the area tidy—ionic liquids can leave sticky residues. Used containers and gloves go into chemical waste, not regular trash. A safe lab stays quiet and boring for a reason.

Watching the Environment

Ionic liquids used to market themselves as “green” alternatives, but research shows some won’t break down easily in water or soil. If you spill or dispose of 1-Octyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate down the drain, you risk contaminating rivers and harming aquatic life. The best practice is to collect all waste, label it, and hand it off to professionals who know how to process these chemicals safely.

Training, Not Guesswork

Having worked with dozens of specialty chemicals, I can say that even confident chemists benefit from plain language training. Every new user should read safety data sheets, learn emergency procedures, and ask for help before working alone. Safety never slows progress; it keeps people around long enough to see the next breakthrough.

Why We Care So Much About Solubility

In school, solubility seems like a dry chapter in a textbook. Once you get into a real lab or start dealing with pain relief pills, acne creams, or something as basic as table salt, the story quickly changes. Solubility drives how much of a substance enters your body or the environment, and how quickly it does so. Pour a scoop of sugar into your coffee. If it dissolves fast, your coffee is sweet right away; if not, you get that grainy taste until you give up and stir harder.

Water: The Universal Challenge

Most of us have at least tried to mix oil and water. It doesn’t go well. That’s because water, a polar molecule, only likes to buddy up with other polar substances. Salt, which separates into charged particles, goes into solution easily. Things like caffeine and citric acid, which can form hydrogen bonds, also disappear in water with little effort. Try dissolving nail polish or black pepper: they’re stubborn, and water can’t do much. The world gets more complicated with drugs that need to dissolve in blood (mostly water) but don’t like being wet. Pharmaceuticals spend millions trying to redesign molecules or wrap them in clever casings just to get better water solubility. If you ever wondered why some painkillers kick in faster than others, check the label—solubility makes all the difference.

Switching to Organic Solvents

Not everything plays nice with water. Many compounds, especially fats, oils, or waxes, do way better in solvents like ethanol, acetone, or chloroform. These organic solvents have very different structures from water. They help dissolve lipstick pigments, clean grease in industry, and break down markers and paint. If you drop essential oils or perfume into alcohol, the scent spreads fast and even. Cleaning up oil stains with soapy water mixes polar and non-polar chemistry, which makes detergents work where plain water fails. Chemists and factory workers often run tests in alcohol or hexane, picking the best match for the task.

Real-Life Messes Solubility Leaves Behind

The quirks of solubility shape the world in ways most of us miss. Take environmental messes. Rain can wash fertilizers and pesticides (soluble in water) into rivers, fueling algae growth and hurting fish. On the flip side, waste oils and some industrial chemicals refuse to dissolve, sticking around in soil and water for decades. Cleanup becomes nearly impossible. Limited water solubility can make life hard for doctors, too. Some treatments for cancer or infections can’t get where they need to be in the body if they won’t dissolve in blood.

What We Can Do About It

Adjusting solubility often comes down to creative chemistry. Some scientists change the molecular shape to balance how a drug acts in water and fats. Others add helper molecules that drag stubborn compounds along. In the world of green chemistry, people look for safe solvents that dissolve the tough stuff without harming workers or the environment. At home, knowing which cleaners or solvents to reach for can save time and keep you safer. Water handles some stains, but for grease and paint, there’s usually a better, less toxic match than what’s under your sink.

Solubility Is More Than a Science Term

This isn’t just about lab coats and glassware. Whether you’re choosing shampoo, picking the right cleaner, or voting on chemical safety rules, solubility plays a role in your day. Understanding which compounds like water, which prefer solvents, and how they shift between environments matters far beyond schoolwork. It touches health, safety, industry, and the planet itself.

Facts in the Bottle

Nobody grabs a bottle of 1-Octyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate to set it on the living room shelf. This ionic liquid shows up in specialized places—university labs, clean chemical facilities, and a few industrial operations. I spent my grad school years tackling similar bottles, with gloves snapped tight and goggles steaming up at the worst moments. Handling this stuff taught me the importance of respecting both its usefulness and risks.

Storage Makes All the Difference

Keep chemicals safe, and the basics almost never change. Use a dry, cool room. Temperatures above standard room temperature may nudge decomposition or coax off unwanted vapors. This compound keeps stable below 30°C, so skip the windowsill or any spot near a radiator or sink with hot pipes. Toss the bottle in with oxidizers, peroxides, or strong acids and you gamble with fires or surprise reactions worth a trip to the hospital.

What always helps: a strong, clearly labeled container—preferably amber glass or a good quality high-density polyethylene. Chemicals always find a way to creep through cheap plastic, and this ionic liquid doesn’t need any temptations. Tight-fitting caps with good threads keep moisture out and stop leaks or fumes. I once watched a poorly closed cap start to corrode the shelf after just a month, so double-checking stoppers never wastes time.

Good labs use secondary containment: plastic bins or trays catch any surprise drips. I still remember an intern learning this lesson the hard way after a teaspoon-sized spill ate through some paint. No singing “just a little bit” if that little bit ends up in the air or on skin.

People and the Planet

Most folks don’t think about the health angle until someone starts coughing or develops a rash. 1-Octyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate presents low volatility, which means the vapor isn't bad at low temperatures, but skin and eyes prefer not to meet it. Gloves, lab coats, goggles: basic gear, every time. In labs I worked in, safety showers and eyewash stations earned their place—not ornaments, but last-ditch backups after a mistake.

Saying Goodbye: Disposal Isn’t a Trash Can Affair

I have seen too many new chemists think a little “liquid” can swirl down the drain. That’s a good way to spread hazardous waste far, fast. Waste like this belongs in a sealed, clearly marked container, set aside for hazardous waste collection. At the university, professionals would arrive each month for solvent pickups. They logged everything and sent it off for high-temperature incineration. That broke down the compound without spewing fluorine or boron byproducts into the environment. Municipal rules usually prohibit pouring any tetrafluoroborate compounds into regular trash or into sewage systems. A single careless pour can disrupt treatment plants or damage local ecosystems.

Improving Habits

Cleaner storage areas make safer storage. Regular checks for leaks, labels in bold, fresh supplies of appropriate gloves and spill kits—these fix half the problems before they start. Staff training and culture matter even more than the best gear. I always appreciated working in places where every team member felt able to speak up about chemical risks. Research grows safer and more productive when people know the routine and care about the environment and each other.