Understanding 1-Octyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide: A Practical Commentary

Historical Development

Curiosity has always pushed chemists to create smarter chemicals. The story of ionic liquids runs back to the search for better solvents, ones that don't evaporate easily or damage the environment the way traditional organic solvents do. Back in the late 20th century, researchers came across imidazolium salts that remain liquid at room temperature. Among these newcomers, 1-Octyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide emerged as chemists tweaked chain lengths and tweaked different substituents on the imidazolium ring. This group of chemicals opened doors to solvents that can be recycled, tailored to different chemical processes, and sometimes even used as reagents themselves. From my perspective in research, the buzz about these ionic liquids has built up over decades because they promised cleaner chemistry without compromising performance.

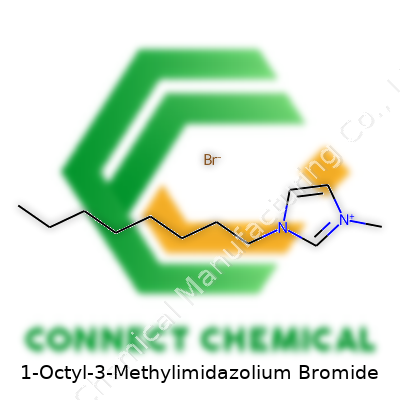

Product Overview

1-Octyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide, often known as [OMIM]Br, stands out as a member of the imidazolium ionic liquid family. Its formula, C12H23N2Br, spells out a balance between a mid-sized hydrophobic tail and a sturdy imidazole backbone. In the lab, you’ll often find it as a viscous, colorless to pale yellow liquid, sometimes appearing as a waxy solid depending on storage conditions. The bromide anion pairs well with the organo-cation, making this salt versatile in both organic and aqueous environments. It bridges gaps between oil-loving and water-loving molecules—a quality that turns out to be endlessly useful in chemical synthesis and extraction.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Pour a bit of [OMIM]Br and you'll notice the viscosity, which speaks to its relatively high molecular weight. It doesn't have a strong scent, which helps in busy research settings where fumes can get overwhelming. The melting point usually lingers around room temperature, but shifts a bit depending on purity. Its solubility leans toward organic solvents, but it will mix with water to a limited extent. This ability to dissolve both polar and nonpolar compounds creates possibilities for reactions that old-school solvents simply can’t handle. The thermal stability appeals to me whenever I run high-temperature syntheses, since the compound barely breaks down until you push temperatures past 200°C. The ionic liquid’s conductivity is another highlight, making it helpful in electrochemical studies and applications.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Companies usually ship [OMIM]Br in sealed amber bottles, labeled with product codes, purity (often >98%), CAS number (a unique identifier for chemicals), recommended storage temperature, and expiration date. Labels also include hazard pictograms, handling guidelines, and batch numbers for traceability. These details matter in practice; tracking purity and storage conditions directly influences the performance in lab reactions, and the emphasis on batch records helps catch any outliers in results. Regulations demand that storage spaces remain dry and cool, with containers tightly shut to keep out atmospheric moisture and contamination.

Preparation Method

Chemists synthesize [OMIM]Br by first alkylating 1-methylimidazole with 1-bromooctane. In practice, this involves mixing equimolar amounts of reactants in a suitable solvent—sometimes acetonitrile or toluene—to speed up the reaction. Gentle heating gets the reaction moving, leading to the formation of the desired ionic liquid. Afterward, purification steps usually involve extraction, rotary evaporation, and sometimes recrystallization if the product turns out as a solid. As someone who has handled ionic liquids in the lab, I know that purification can take patience, since small impurities impact the liquid’s color and reactivity. Overall, the process turns out a relatively pure product, ready for fine-tuning or direct use.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The chemical backbone of [OMIM]Br can accept further modifications, allowing researchers to tailor the alkyl chain length or swap out the bromide for another anion, like tetrafluoroborate or hexafluorophosphate. These tweaks impact properties like melting point, solubility, and toxicity. In chemical reactions, this ionic liquid frequently acts as both a solvent and a catalyst, especially in organic transformations such as alkylation and nucleophilic substitution. In my own experience, using [OMIM]Br as a solvent for reactions has sometimes improved yields and cut down on byproducts, thanks to its unique solvent environment. Some labs even use it in recycling loops, where its non-volatile nature comes in handy for green chemistry applications.

Synonyms & Product Names

You might find [OMIM]Br listed under several names in catalogs and scientific papers. Variations include 1-Octyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide, Octylmethylimidazolium Bromide, and OMIM Br. Chemical suppliers often tag the product with proprietary codes or alphabetical prefixes. Researchers must pay attention to these synonyms to avoid confusion and ensure they’re using the intended compound, especially since a small change in the alkyl chain can create a whole new material with different chemical behaviors.

Safety & Operational Standards

Lab safety guides recommend gloves, goggles, and lab coats when handling [OMIM]Br, since it can irritate the skin and eyes on contact. Keep the product away from strong oxidants and acids, as it could lead to unwanted decomposition or hazard. Companies include safety data sheets (SDS) with every shipment, detailing spill management practices and fire hazards. Having worked with this material, I’ve learned that ventilated hoods prevent unnecessary exposure, especially during weighing and mixing. Disposal requires proper protocols to avoid environmental impact, as ionic liquids, though greener than many older solvents, still bring concerns about persistence in soil and water.

Application Area

Uses for [OMIM]Br stretch across fields such as catalysis, electrochemistry, material science, and even biotechnology. In my projects, I’ve used it to solubilize stubborn chemicals that wouldn’t dissolve anywhere else, and as a medium for forming nanoparticles. Industrial processes benefit from its stability under heat and voltage, making it a favorite in battery research and organic synthesis. The ability to extract precious metals from complex mixtures also draws attention from environmental engineers and recycling specialists. Some research even explores medicinal and pharmaceutical use, since the imidazolium backbone interacts favorably with certain biologically active molecules.

Research & Development

Academic groups continue probing [OMIM]Br for new functions, including drug delivery, protein folding studies, and energy storage. The ionic liquid structure leaves room for fine-tuning, which researchers exploit to create less toxic or more biodegradable alternatives. Grant proposals often focus on designing new versions of these chemicals with improved application in mind. In meetings with colleagues, I’ve heard plenty of excitement about mixing these materials with polymers or nanoparticles to yield hybrid materials for smart coatings, membranes, or selective separations.

Toxicity Research

While [OMIM]Br and other imidazolium-based ionic liquids look like cleaner alternatives, toxicity remains a concern. Animal studies and aquatic toxicity research show that longer alkyl chains generally boost toxicity, both for environmental microorganisms and in animal tissue. For [OMIM]Br, toxicity is moderate, with some reports of effects on fish, algae, and water insects at high concentrations. Toxicologists stress the need for proper containment, recycling, and disposal to keep these risks in check. My own reading of recent literature suggests that optimizing chain length and exploring biodegradable anions offer the most promising routes to safer, more sustainable ionic liquids. Regulatory agencies started to pay more attention to these factors, tightening guidelines for research and industrial use.

Future Prospects

Interest in ionic liquids like [OMIM]Br keeps growing as industries search for less hazardous, more effective chemicals. Upcoming research points toward smarter design using computational chemistry, which predicts even safer and more specialized imidazolium salts. There’s a strong push to combine renewable resources, such as using fatty acids or biomolecules as building blocks. From environmental cleanup to advanced manufacturing, [OMIM]Br holds potential—if researchers and industry partners keep a critical eye on safety, scalability, and cost. Having followed several patents and industrial reports, I see momentum toward integrating these materials into processes like battery electrolytes, recyclable catalysts, and even biodegradable solvents. The future will bring more collaboration across disciplines as scientists and engineers work to unlock the full capabilities of this fascinating chemical.

What’s the Deal With 1-Octyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide?

In any lab where researchers chase after greener reactions or puzzle through thorny problems in separation science, 1-octyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide—let’s call it [OMIM]Br—makes a regular appearance. We’re talking about an ionic liquid. This stuff doesn’t act like water, oil, or the usual chemicals piling up in storerooms. Instead, it stays liquid down at low temperatures and carries strong electrostatic charges from its imidazolium head and chunky octyl tail.

I’ve spent late afternoons hunched over test tubes and glassware, and more than once I’ve seen [OMIM]Br swing results from “useless” to “promising.” Anyone who’s tried to pull rare metals or spent an hour distilling off toxic solvents will get it. Ionic liquids cut out a lot of old pollution-heavy steps for chemists, and [OMIM]Br lands near the top of that list because of its sweet spot between solubility and chemical stubbornness.

Driving Greener Chemistry

What ranks as breakthrough for green research? Swapping out volatile and toxic solvents for something safer, for one. [OMIM]Br pours in as one of those “designer solvents” that won’t catch fire, stink up the lab, or boil away easily. Chemists hunting down gold, palladium, or rare earths will stir in this ionic liquid instead of nasty stuff like chloroform. Once blended, [OMIM]Br helps dissolve, transport, and separate out metals without dumping poison into waterways or trashing air quality.

A big push comes from regulations. The European Union put pressure on labs with strict REACH guidelines and now plenty of projects demand ionic liquids like [OMIM]Br in place of legacy solvents. It’s not perfect—there’s always a tradeoff when you scale up—but seeing waste drop and safety rise shifts the game for a lot of teams.

Extraction Without the Drama

People in mining and recycling circles probably argue the most about separation science. Take e-waste: pulling out precious elements looks easy on paper, but most methods eat up acids and end up with toxic sludge. [OMIM]Br steps in to grab metals from scraps, recovering what’s valuable with a lot less mess. From batteries to old circuit boards, this ionic liquid keeps its cool during extraction and rarely reacts with other things in the mix. Researchers published work in journals like Green Chemistry and Separation and Purification Technology showing extraction rates go up—plus, less acid means less risk for technicians.

A Cleaner Route for Catalysis

Not every scientist has the luxury of big budgets, so running catalytic reactions with recyclable materials makes sense. [OMIM]Br clicks with catalysts, lending a “solvent cage” effect that boosts performance for hydrogenation, carbon-carbon coupling, and oxidation. I’ve tinkered with reactions where the same batch of [OMIM]Br worked three or four times. That’s cash saved and less headache during disposal. These ionic liquids even tolerate heat and light better than water or methanol, making them practical for industry and pilot-scale setups.

Future Hurdles and Better Choices

No chemical solves every problem without giving up something on safety, price, or lifecycle. Toxicity data on [OMIM]Br isn’t bulletproof, and nobody wants green chemistry that leaves a new kind of pollution behind. Research groups in Europe and Asia chase down ways to recover and recycle it after use. Some teams test shorter or longer “tails” on the molecule, looking for the right combo of power and safety. Universities teaching lab safety now spend time debating the balance between innovation and responsible disposal.

If you’ve ever tried balancing a research budget, dodging hazardous waste bills, and hoping for fewer headaches with regulations, it starts to make sense why researchers keep reaching for [OMIM]Br. This little ionic liquid changes the calculations—making tricky chemistry cleaner, safer, and just plain simpler.

Why Storage Matters for Ionic Liquids

1-Octyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide belongs to a group called ionic liquids. Their benefits fill research journals—low volatility, powerful solvents—but these perks mean nothing if the compound degrades in storage. I’ve cleaned up enough ruined chemicals to know: cutting corners on storage leads to wasted time, shredded budgets, and sometimes, unexpected safety risks. Like most imidazolium salts, this one draws water from the air. A little care goes a long way toward keeping your materials in top shape for reactions or scale-up.

Shield the Compound from Moisture

Ionic liquids, especially those with longer alkyl chains, love drawing moisture from the air. Leaving a vial uncapped for just a few minutes on a humid day, you might see clumps or changes in texture. I learned early on: returning even a ‘dry’ sample to storage after it’s soaked up moisture can throw off your chemistry, especially where precise stoichiometry matters. Use tightly sealed, screw-cap containers—glass works best. Drop in resealable desiccant pouches (silica gel or molecular sieves) before closing things up, and check them occasionally. Lab desiccators may look unfashionable in a modern wet lab, but their power hasn’t aged one bit.

Keep Your Cool: Temperature Settings

1-Octyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide stays stable at room temperature if it’s not exposed to blazing heat, open flames, or direct sunlight. The material can degrade under prolonged heat, so pick a cabinet or drawer away from heating elements or sunny windows. In my own lab stints, temperature swings—especially in older university buildings—have led to surprises. Try 18-25°C as a steady range. No need for a fridge unless the specification states otherwise, but a cool, steady spot beats the top of a radiator or a sunlit shelf every time.

Avoid Contamination: Label and Segregate

Once, after grabbing a poorly labeled vial, I had to repeat a week’s worth of synthetic work—nobody enjoys that. Mark everything with the full name, concentration, batch number, and date opened. Keep it separate from acids, strong oxidizers, and anything that might react, especially in a chemical stockroom crowded with organics and inorganics. Cross-contamination in a busy teaching lab isn’t rare, but it’s avoidable with a bit of discipline. I recommend a dedicated shelf or clear bin for ionic liquids. If your chemicals share a fridge, store them in secondary containment to catch any accidental spills.

Personal Experience Meets Good Practice

From research assistant gigs through process chemistry roles, I’ve seen mishaps both small and spectacular. One time, an ionic liquid container lost its label, leading to hours of spectral analysis just to confirm its identity before use. Trust me, nobody wants to be that person. Common sense rules apply: avoid stacking heavy items on top, keep chemicals reachable, and make it easy for the next person to find exactly what they need. Less confusion and cleaner results follow from these habits.

Smart Solutions for Efficiency and Safety

Buy only what you expect to use in a reasonable time frame, since opening and closing containers over months can accelerate degradation. Automated inventory systems can help track expiration and opening dates. A system for rotating stock, just like in your kitchen, cuts down on waste. In larger labs, regular training prevents simple mistakes—like using the wrong solvent for cleaning or storing, or leaving the chemical bench exposed during humid weather.

Chemistry’s about control, not just in the reaction flask, but at every step leading up to it. Proper storage takes minutes, but those minutes protect your science, your budget, and your team. That’s experience you can trust, not just a line from a handbook.

Understanding the Risks Behind the Chemical Name

Many chemicals come with long names and even longer safety data sheets. 1-Octyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide falls into that class of compounds known as ionic liquids, which have turned up as solvents and components for chemical reactions in research labs. The chemical lets scientists replace more traditional, volatile organic solvents, and its presence in a lab signals progress toward cleaner technologies. Yet, any new chemical deserves a clear look at risks.

The Science: What We Know

People often assume ionic liquids come with less environmental baggage than old-school solvents. For 1-octyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide, the reality gets a bit more mixed. The substance doesn’t evaporate easily. That brings some relief — it won’t fill the air with unhealthy vapors like acetone or benzene. Still, just because a liquid doesn’t go airborne doesn’t mean it’s entirely safe.

The real questions come up with handling, spills, and the possibility of getting the compound on skin, or in the eyes. Scientists looking at imidazolium ionic liquids notice some trends: these substances stick around in the environment, don’t break down easily, and can cause trouble for aquatic life. Imidazolium derivatives in general show moderate to high toxicity to aquatic organisms, and this version, with its long octyl chain, sits on the higher end of toxicity among its peers.

Personal Experience: Navigating Chemical Handling

The first time I worked with these ionic liquids in a research lab, I kept gloves on and washed up like I was prepping food in a hospital kitchen. My supervisor drilled home a core principle: never treat a new chemical as harmless, no matter what the greener advertising says. Even trace splashes can irritate the skin, and in a busy lab, a little carelessness turns into a ruined day fast. No matter how sleek these liquids seem, there’s always a trade-off. Less flammable doesn’t mean non-toxic; odorless doesn’t mean you want it in your system.

Anecdotes in the lab showed mild skin irritation from minor exposure. Some colleagues with sensitive skin noticed redness and itching. Cleaning up after a spill took more effort than with volatile solvents, as these compounds grip surfaces. It pushed us to rethink our safety procedures: double gloves, out-of-reach storage, and stricter labeling.

Looking At Health Effects and Environmental Impact

Research into long-term toxicity for humans runs thin, since these liquids are still relatively new. Animal and cell studies give some clues. Rats exposed through ingestion and skin contact show signs of organ stress — liver, kidneys — so routine exposure probably wears down the body over time. If a chemical harms aquatic species, there’s good reason to believe it can cause chronic issues for humans, just at different doses and through different paths.

For the environment, persistence stands out as a real concern. These compounds settle into water tables and don’t break down quickly. Runoff from labs and factories slowly builds up, threatening delicate habitats. Once in a stream, a little goes a long way in harming fish and tiny freshwater life. It shows that switching chemicals doesn’t automatically mean reaching a safer endpoint for the environment.

Practical Solutions for Safer Labs

Each researcher or technician working with this compound should treat it with genuine respect. Training on safe handling helps, as does keeping rigorous accident protocols in place. Proper disposal becomes non-negotiable: no pouring down the drain, no hasty wipes with paper towels. Containerizing waste and using professional chemical collectors may cost extra, but that trade-off protects both people and wildlife.

Regulators and companies benefit from frequent reviews of toxicity data and real-life spill reports. Substituting this ionic liquid with a compound known for quicker breakdown can reduce the footprint. An open conversation between manufacturers, labs, and environmental scientists supports informed choices, and steady research pushes for ever-safer alternatives.

Understanding the Backbone

1-Octyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide draws curiosity for people working with ionic liquids. The chemical structure starts with an imidazolium ring—a simple five-membered system containing two nitrogen atoms. This ring forms the base and kicks off the unique abilities of the compound. At the one position of the ring, chemists attach an octyl group—eight carbon atoms forming a straight hydrocarbon chain. It’s not just a random addition. The length of this tail shapes the way this material behaves, especially in solutions and mixtures. The three position gets a methyl group, a one-carbon sidekick that rounds out the organic part.

On the salt side, the compound partners with bromide. This halide isn’t just hanging around; it balances out the charge from the positively charged imidazolium core. The pairing is tight on the molecular scale, yielding a room-temperature ionic liquid under many conditions.

Drawing Connections: Real World and Laboratory Relevance

During years in the lab, it becomes clear that 1-Octyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide doesn’t show up just because someone likes complex names. The presence of a long alkyl chain makes this ionic liquid useful for dissolving a wide range of substances. Unlike water, which struggles with greasy materials, this compound holds both organic and inorganic molecules with surprising ease. This flexibility means breakthroughs in green chemistry. Classic solvents come with fire risks, volatility, and toxicity. Ionic liquids like this one step in, offering negligible vapor pressure and lower flammability.

Researchers found this structure offers potential for extractions from tough feeds, such as removing heavy metals or separating troublesome dyes. Chemists exploring ways to make batteries and solar cells more stable look this way because ionic liquids resist evaporation and decomposition under stress. The octyl tail increases solubility for hydrophobic targets, pushing the range of possible applications further than a methyl or ethyl derivative ever could.

Practical Considerations and Solutions

It’s not all upside with 1-Octyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide. The environmental impact takes center stage. Some studies raise questions about aquatic toxicity and biodegradability—long alkyl chains don’t break down fast once they leave the bench. Responsible laboratories now chase alternatives or tweak processes to recycle and recover these salts. It’s possible to cut down environmental risk by using closed-loop systems, or by pairing these ionic liquids with established waste treatment protocols. Students in chemical engineering courses now look at ionic liquid structure-function relationships. This approach delivers better and safer compounds, without leaving legacy pollution.

Knowledge grows when scientists look beyond the obvious. The detailed structure of 1-Octyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bromide, from the imidazolium head through the octyl tail to the bromide counterion, shapes how this material opens doors for new technologies. It’s worth every bit of scientific attention—and every question about how it can fit in a cleaner, more efficient laboratory future.

Getting to Know the Chemical

1-Octyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide shows up in chemistry labs and some manufacturing spaces as an ionic liquid. Its low volatility helps with green chemistry experiments, though low vapor doesn’t mean harmless. Harm can come from skin contact, inhaling dust, or spills that find their way into drains. Strong gloves, safety goggles, and lab coats become basic gear, not just optional add-ons. Splashing a bit onto bare skin or breathing in any powder during a transfer isn’t far-fetched. It’s easy to think a small amount won’t hurt, but stories of persistent rashes, headaches, or worse aren’t just science fiction.

Why Caution Matters

Government agencies like OSHA and the CDC haven’t set strict exposure thresholds for this ionic liquid yet, but that doesn’t signal safety. Experience in the research world taught me that sometimes the biggest risks show up years later. Ionic liquids slipped past early hazard radars for years, but scientists now connect many of them to toxicity in aquatic life and potential health effects in people if handled carelessly. The EPA’s Toxic Substances Control Act is catching up, not sitting back. I once watched as a colleague ignored recommended protection, later regretting it as they struggled with irritation and near-missed a trip to the clinic.

Responsible Handling in the Lab

Real safety means treating unknowns with respect. Prepare as if things will go wrong, not right. Gloves made of nitrile or butyl outlast latex. Working inside a chemical fume hood stops dust from entering the room, and spill trays or secondary containment prevent lively chemicals from leaking off the bench. Spill kits for liquids are handy, but a tech with experience, not just a manual, helps avoid panic when a beaker tips or a bottle cap goes flying. Good labs keep eyewash stations and chemical showers clear of clutter. Folks new to these measures can benefit from short, hands-on safety briefings from someone with scars and stories, not just diplomas.

Practical Disposal Moves

Pouring anything down the drain might feel easy, but this ionic liquid would travel quickly through plumbing and sneak into water treatment facilities completely unmonitored. Once there, the chemical remains active, quietly damaging fish, plants, and all the things downstream locals depend on. Instead, seal up the waste in a correctly labeled, strong container—something that’s been double-checked for leaks especially after a day of use. Waste should get logged in a designated hazardous materials journal, with staff scheduling regular pickups through a licensed chemical disposal vendor.

If the lab generates a lot of this waste, segregation helps—mixing with solvents or acids multiplies the disposal headache. I’ve seen mismanagement turn a small cabinet into a hazardous swamp, causing panic during surprise audits. No one enjoys cleaning up the aftermath or facing steep waste disposal bills when rules get ignored.

Pushing for Change and Protecting the Community

Training sessions run by actual chemists or hazardous waste experts—folks who know what an accident smells like—make protocols stick. Posting clear checklists by disposal stations helps catch mistakes before they cost time or harm. Students, researchers, and staff should speak up if supplies run low or safety labels wear off. Making safe disposal standard goes beyond a single lab or plant; mishandling here can spiral into bigger environmental and health issues elsewhere.

It’s tempting to shrug off the rules as overkill, especially during busy stretches. My own experience taught me: one minor shortcut often leads to a string of extra chores, fines, or even preventable injuries. Respect for chemicals starts small, with one glove, one container, one honest log. These everyday choices matter most.