1-Octyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dicyanamide: Context and Commentary

Historical Development

The history of ionic liquids stretches back to the early 20th century, but true commercial momentum began after the 1990s, when researchers started realizing these “designer solvents” could upend how industries handle tough chemistry. 1-Octyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dicyanamide (abbreviated as [OMIM][DCA]) entered the discussion as chemistry labs worldwide sought alternatives to harmful organic solvents. The need for safer, greener, and more adaptable reaction media shaped the exploration of imidazolium-based ionic liquids. Those working on catalysis, separation, and electrochemistry started including dicyanamide anion as an option for improved thermal and electrochemical properties. This compound didn’t just pop up overnight; it’s the product of decades of incremental shifts in how chemists think about liquids beyond water and typical organics.

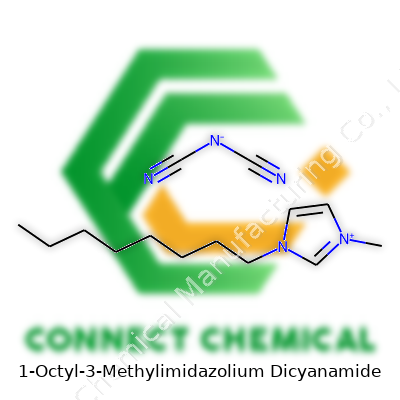

Product Overview

[OMIM][DCA] belongs to the family of room-temperature ionic liquids. The name signals both structure and utility: a long octyl chain for lubricity, a methyl group for fine-tuning polarity, tied to an imidazolium cation, balanced by the reactive dicyanamide. You find this material as a clear to pale yellow liquid at room temperature, stable enough for repeat lab handling and robust enough to serve niche manufacturing needs. You see it in bottles labeled for research, but increasingly, industrial partners eye it as a next-generation solvent, catalyst co-factor, or extraction fluid.

Physical & Chemical Properties

The most striking feature lies in its physical state; staying liquid below room temperature thanks to its highly tunable structure. The octyl chain stretches the cation, reducing the melting point to somewhere between -5°C and 10°C, with boiling points far out of reach of most normal labware. It resists water absorption much better than shorter-chain analogues, so storage doesn’t require the same paranoia about humidity as the earlier generations of ionic liquids. Visually, it shows up as a viscous, syrupy liquid, almost oily but slicker, and it rarely leaves residue that ordinary glassware can’t shed. Chemically, the compound resists oxidation under environment-standard conditions but reacts strongly under the influence of powerful oxidizers and strong acids. Conductivity measures show lower values than water but far higher than mineral oils, which speaks to a balance between ion mobility and overall viscosity.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

On a standard label, manufacturers display purity (usually above 98%), water content (below 0.2%), and halide/metal contaminant traces (in the range of a few ppm). The Molecular Formula, C12H20N6, and a molecular weight around 260.33 g/mol, make stock management and calculations more approachable in lab settings. Appearance gets noted for color and clarity, with periodic lab reports backing claims that a faint yellow hue points to ultra-trace impurities. Companies shipping this product in regulated markets stress compliance with REACH or TSCA for the EU and US, providing guidelines about bulk and storage conditions—dense, high-purity liquid, packed in tight-sealed, inert containers to prevent caking or accidental polymerization.

Preparation Method

Synthesizing [OMIM][DCA] takes a two-pronged approach. Chemists start by synthesizing 1-octyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide via quaternization. Mixing 1-methylimidazole with 1-bromooctane under controlled temperatures produces the desired imidazolium salt. After purification, metathesis brings in sodium or potassium dicyanamide, replacing the bromide with the dicyanamide group through aqueous extraction and washing. Partitioning finishes the job by separating the ionic liquid from the aqueous by-products. The final liquid receives multiple washes with organic solvents and gentle vacuum drying, yielding a pure, low-water-content liquid. The process isn’t new, but the refinement of purification techniques means labs and companies can scale production without letting cost or impurity levels run wild.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

In hands-on chemical processes, [OMIM][DCA] acts as a non-volatile solvent and co-reactant. The dicyanamide anion reacts in certain situations to form triazines, letting chemists use it in the synthesis of nitrogen-rich heterocycles. Under high voltage, this ionic liquid supports redox shuttling in electrochemical cells. Its structure doesn’t just sit idle; thermal degradation produces volatile nitriles when exposed to excessive heat. Occasionally, devising new derivatives means modifying the alkyl chain or swapping methyl for ethyl, giving rise to a family of similar but slightly tailored ionic liquids.

Synonyms & Product Names

You’ll find this chemical under names like 1-octyl-3-methylimidazolium dicyanamide, OMIM DCA, C8MIM DCA, or sometimes the simple shorthand [OMIm][DCA] in research papers and catalogs. Trade names vary by manufacturer, but the systematic nomenclature or recognized acronym usually leads the pack. In lab books, practical scientists just call it “the dicyanamide IL with octyl” to save breath and avoid letters.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling ionic liquids has gotten much safer since the early days of these compounds. I’ve seen labs treat [OMIM][DCA] with the same respect as strong cleaning agents—gloves, goggles, good ventilation, and a firm “no-drain” rule on disposal. The compound irritates skin and eyes upon direct contact, and inhaling its mist or vapor produces strong respiratory effects, so fume hoods remain non-negotiable. Prolonged exposure risks organ toxicity, mostly inferred from analogues, but smarter use of containment keeps incidents rare. Modern safety data sheets include explicit first aid and spill cleanup instructions, and companies supplying large quantities insist on full risk assessments before approving shipments.

Application Area

[OMIM][DCA] operates in a surprisingly wide range of technical fields. Electrochemists use it as a medium for supercapacitor research. Drug developers explore it for phase transfer catalysis, chasing reactions that fail in water or traditional solvents. Textile finishers look at it for dye extraction and clean-up, while metal workers think about it as a safer alternative for polishing solutions and electrolyte plating of rare metals. Environmentally-aware industries use its low volatility and resistance to oxidation for waste minimization in solvent exchange processes. Analytical chemists rely on its strong solvent properties to dissolve stubborn polar or nonpolar samples prior to chromatography. Each field pushes for more sustainable, less hazardous alternatives, and [OMIM][DCA] fits that mold better than most.

Research & Development

Research keeps expanding as more institutions invest in green chemistry. Labs keep testing [OMIM][DCA] for recyclability, both in solvent recovery and as part of closed-loop synthesis systems. Analytical chemists dig into solubility and partition coefficients, finding that unique ionic makeup creates niche selectivity for complex mixtures impossible to resolve otherwise. Studies on electrochemical stability extend to advanced batteries and even potential fuel cell technologies. Some teams explore using it as a replacement for volatile organic solvents in traditional extraction procedures, hoping results match the theoretical promise of lower emissions and easier product purification. My own reading of current literature suggests a wave of innovation focused on hybrid materials containing [OMIM][DCA] as a core structural or functional element—a trend with staying power as labs wrestle with tightening environmental rules.

Toxicity Research

As much as proponents tout its green credentials, [OMIM][DCA] still demands deep scrutiny on toxicology. Data from the last several years points to low acute oral and dermal toxicity, but chronic exposure effects remain under investigation. Early studies with model aquatic organisms such as Daphnia and zebrafish reveal moderate bioaccumulation and disruption at higher concentrations. The dicyanamide component raises red flags about nitrogen cycling in ecosystems, and wastewater studies measure slow but consistent persistence if treatment fails to break it down properly. The compound resists breakdown in normal treatment plants, so researchers look to advanced oxidative degradation or bioremediation. Most workplace guidelines recommend treating these liquids as potential hazardous waste, and responsible handlers always choose waste minimization procedures and closed systems over discharge.

Future Prospects

Industries face constant pressure to move away from toxic, flammable, and high-emission solvents. [OMIM][DCA] and its kin look poised to take on bigger roles in sustainable process chemistry. As cost falls and large-scale synthesis streamlines, more sectors might turn to this ionic liquid for extraction, catalysis, or electrochemical work. Further advances in toxicity testing and waste treatment could bolster its case as a next-generation solvent that aligns practical needs with environmental stewardship. Ongoing refinements may improve biodegradability or biocompatibility, making future derivatives even safer. The real test lies in whether research, regulation, and market demand can keep propelling these substances away from the lab bench into manufacturing settings where safety, cost, and sustainability become daily production concerns.

What Sets 1-Octyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dicyanamide Apart

1-Octyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dicyanamide doesn’t roll off the tongue. Most working chemists and engineers, though, know it as a valuable ionic liquid in the lab or factory. I remember seeing this deep orange solution in the corner of a research space, always being measured for the next round of tests. Its true importance comes from its ability to solve problems that stump everyday solvents—cleaner extraction, stable electrolytes, reaction help, and sometimes straight-up safer handling.

Chemical Separations and Greener Chemistry

Teams around the world search for ways to pull metals from raw ores or recycle batteries. 1-Octyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dicyanamide’s biggest claim to fame lies here. It handles tough dissolving jobs that water, methanol, or even acetone can’t. Certain rare earth metals—what you find in magnets or phone screens—come out of waste streams or mineral sludges with its help. The payoff is less reliance on harsh acids and easier cleanup. Peer-reviewed journals back this up. I’ve read more than a few articles in Green Chemistry and ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering showing lab data: recoveries jump up, hazardous output drops down.

Role in Energy Storage and Future Batteries

Flammable solvents in lithium and sodium batteries catch enough headlines already. Ionic liquids like this one don’t catch fire so easily. Battery engineers want something stable, safe under pressure, and tolerant of ugly high or low temperatures. Here’s where this dicyanamide salt comes in. Its cation tail brings flexibility and conductivity. I remember my old group running conductivity tests at –20°C and getting results that put traditional mixtures to shame. Battery prototypes built on these properties last longer and put up with repeated stress that kills competitors.

Catalysis—Speeding Up Chemical Reactions

In the chemical industry, efficient catalysts cut waste and strength out bottom lines. 1-Octyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dicyanamide proves useful in reactions that create pharmaceutical intermediates or polymer building blocks. Its unique ionic structure means it holds certain metals close, tunes acidity, or even dissolves entire catalyst complexes others leave behind. I spoke with a pharma process chemist who pointed out that using these ionic liquids allows for selective product pickup, less troubleshooting, and easier purification. Practical experience shows the reaction vessel sometimes stays much cleaner, saving time and money.

Cleaning Up Environmental Messes

Industries deal with toxic metal contamination, whether from electronics recycling or old smelters. Ionic liquids, including dicyanamide types, trap and separate metals like lead, copper, or nickel from polluted water or soil. Water samples that once failed environmental standards often clean up faster with these salts mixed in. Public and private labs report lower costs and lower risks to workers, getting closer to what regulators demand.

Safer, More Efficient Manufacturing

One thing’s clear—technologies built with 1-Octyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dicyanamide bring flexibility to engineers. Tweaking manufacturing solvents, building batteries, or recycling waste becomes more straightforward and less messy. Companies moving toward greener, more resilient processes find value here. There’s no universal fix for complex chemistry, but these ionic liquids give real, tested options.

Understanding What We're Working With

1-Octyl-3-methylimidazolium dicyanamide falls into the family of ionic liquids. You find its name in scientific journals and industry papers when people talk about solvents for batteries, cleaners, or high-tech manufacturing. On the surface, it looks like a perfect fix: low vapor pressure and non-flammability have made it popular in labs and a few pilot plants. The chemical industry sometimes treats the ‘green’ label like a badge of honor here because the substance doesn’t evaporate or explode as easy as traditional solvents. That sentiment needs a reality check.

Looking at Human Health

Even if something doesn’t give off toxic fumes, you can’t call it safe just because you can’t smell it. Research has pointed out that some imidazolium-based ionic liquids raise red flags for cell health. Tests with dicyanamide salts (the part that gives this chemical half its name) show stress responses in human liver and nerve cells in petri dishes. That means cells start dying or stop dividing like they should. Scientists at European labs have flagged possible connections to oxidative damage and enzyme interference, especially when these salts break down. Dicyanamide ions break apart into cyanide under harsh conditions, and that’s a compound you don’t want in your body—cyanide clogs up how oxygen flows in your blood.

Direct skin or eye contact leads to irritation for some people. No industrial accident stories have gone public so far, probably because this chemical hasn’t gone mainstream like acetone or toluene, but the risk rises as its use spreads. Wearing gloves, using fume hoods, and keeping careful inventory of spills aren’t empty rituals; they grind down the odds of an emergency. In my last chemistry job, nobody wanted to get lazy about handling oddball solvents, no matter what a safety data sheet claimed.

Environmental Impact: Green Promise or Greenwash?

Marketing claims love calling ionic liquids “environmentally friendly,” but persistence tells you more than buzzwords. 1-Octyl-3-methylimidazolium dicyanamide wants to stick around in water and soil. Rain, time, and soil bacteria won’t break it down as easy as an old-school organic solvent. A European Chemicals Agency report marks it as not readily biodegradable, and those dicyanamide ions don’t play nice with aquatic life. Fish and algae react badly even at low exposures—a few milligrams per liter can slow growth or tip off stress reactions. Accidents, sloppy disposal, or leaky storage containers send these salts into rivers and groundwater, where their persistence turns short-term mistakes into long-term headaches.

Data on large-scale spills stays thin, mostly because researchers and regulators don’t have decades of history to draw from, unlike with oil or lead. But the basic chemistry hints at risk: low volatility means less air pollution, but that same stability means anything dumped stays put.

What Makes Sense Going Forward

No silver bullet exists for chemical safety. Substitution makes sense—only choose these kinds of ionic liquids if nothing safer does the job. Invest in proper waste capture, sealed storage, and good ventilation, not just to meet lab standards but to cut exposure and off-site contamination. Companies and labs need to demand and share more toxicology research before ramping up production. For regulators, tightening disclosure rules and following up with real-world water and soil monitoring helps spot trouble before it spirals. If chemists, managers, and policy-makers all pull in the same direction, the workhorse solvents of the future won’t come with a hidden toxic bill.

Getting Real About Why Stability Counts

Growing up in a small lab where Dad stored every bottle with almost obsessive care, the topic of chemical stability never felt far away. It’s not just about whether a compound will stay “intact.” It’s about waste, costs, safety, and plain old peace of mind. Take 1-octyl-3-methylimidazolium dicyanamide, an ionic liquid that pops up in research and some niche industrial processes. If this compound breaks down, lab budgets evaporate, experiments fizzle, and sometimes, worse poisons form than anyone bargained for.

Heat, Moisture, and the Elephant in the Room

The stability of this dicyanamide salt takes a real hit at higher temperatures. Studies suggest once you get above 120°C, decomposition enters the conversation quickly. Cyanamide and other nitrogen-based byproducts start showing up, bringing questionable toxicity with them. My old mentor used to pull out the thermal balance and glare at me sternly: “Don’t go overboard just because it’s an ionic liquid.” His suspicion proved well-placed. While it outperforms many standard solvents in low- and mild-heat reactions, it pays not to push these boundaries.

Moisture in the air brings another layer of headache. Those imidazolium-based liquids aren’t fans of water, and even modest levels can prompt hydrolysis or slow but steady structural changes. This usually means more impurities down the line, not just in the laboratory but in waste streams, too. Simple humidity you ignore during storage ends up stretching project deadlines—and sweetening the bill from waste management companies.

Light and Air: Less Obvious, Just as Tricky

Labs with big south-facing windows sometimes forgot to cover their samples in direct sunlight—a mistake I’ve made. Under strong UV or just persistent daylight, you start seeing breakdown. The dicyanamide part feels this stress most. You get color shifts, odd smells, and new peaks in the spectra. If you’re chasing consistent results, covering your glassware turns into a true act of self-care.

Oxygen brings problems, too. Not every ionic liquid stays cozy around air. For 1-octyl-3-methylimidazolium dicyanamide, slow but real oxidation can change its properties over weeks. You notice this when preparing reference standards and find small, unexplained differences. Sometimes that means the difference between publishable data and a failed experiment.

Bigger Picture: Safety, Policy, and Environmental Worries

In the US, the EPA keeps a close eye on dicyanamide salts because of unclear long-term impacts. Water solubility and mobility can send these chemicals far downstream, raising flags in wastewater analysis. People who re-use these ionic liquids in continuous processes talk about slow but significant buildup of byproducts, some of which resist typical treatment. From firsthand frustration, no one wants the extra paperwork—or to face pricey remediation down the line.

Some labs have shifted to using glove boxes, silica gel, and vacuum sealing to slow down decomposition. Others worked up alternate ionic liquids or built in monitoring steps to catch tiny changes before full batches go off-spec. Quality control saves more than money here. It keeps students and staff safer, cuts down on questionable environmental releases, and allows honest labeling—something funders and journals now demand.

Toward Practical Solutions

Storing 1-octyl-3-methylimidazolium dicyanamide dry, cool, and away from sunlight grew into policy at my last workplace. Using nitrogen atmospheres became second nature, like locking up biohazards at night. Routine GC-MS screens kept manufacturing honest. It sometimes feels like overkill until you tally up the cost of a batch gone bad. Support from institutions, clear safety data, and funding for better degradation studies will help everyone from grad students to manufacturers. In chemistry and life, stuff that holds together tends to matter most.

Understanding What You’re Working With

Dealing with 1-Octyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dicyanamide, often shortened to OMIM DCA, means paying close attention to chemical safety. This compound belongs to the family of ionic liquids—a class known for low volatility and great thermal stability. Some folks get lulled into a false sense of security because these liquids don’t give off the telltale fumes of danger. Don’t fall for it. Just because it doesn’t smell harsh doesn’t mean it can’t harm you.

Decent Storage Matters

Direct experience in a busy lab taught me the value of proper storage. OMIM DCA holds up under moderate conditions but still demands respect. Store it in tightly closed containers, made from materials that hold up against strong chemicals. Glass bottles or high-grade plastic containers work best. Humidity can mess with it, so keep things cool and dry. A general-purpose chemical storage cabinet away from direct sunlight does the trick. Sunlight can help break down some organic compounds over time, so avoid window ledges and warm corners.

Handling Isn’t a Casual Affair

OMIM DCA feels slick and can spill easily. My first encounter with this liquid on a lab bench drove home a point—good habits save headaches later. Always wear nitrile gloves, even if handling a sealed bottle. Lab coats and splash goggles add the needed layer between your skin and any mistake. This isn’t exaggerating risks; ionic liquids can soak into your skin and bring along toxic effects.

Spills need attention right away. In my own work, I always kept absorbent pads nearby and avoided working over cluttered benches. If anything drips, blot the area with a pad and dispose of the waste according to your institution’s hazardous disposal plan. OMIM DCA shouldn’t go anywhere near a drain. Ionic liquids have uncertain environmental impacts; better to collect and send them out with chemical waste pickups.

Ventilation and Common Sense Go Hand-in-Hand

Some researchers talk about how these ionic liquids seem “greener” than traditional solvents. Even so, don’t treat them like something as harmless as water. Work in a well-ventilated space. Fume hoods give added peace of mind, especially around quantities larger than a few milliliters. I’ve seen accidents happen by thinking a drop or two could be handled anywhere—splashes and vapors don’t ask for permission about where they go.

Labeling and Record Keeping

Even senior chemists can misjudge clear or slightly yellow liquids. Always label every bottle in storage with the full chemical name, the date received, and your initials. This sounds simple until a few months pass and you’re trying to remember where a mystery bottle came from. I once retraced hours of work due to a missing label; those hours are better spent elsewhere.

Training and Ongoing Awareness

Safety training isn’t busywork. If you’re new to handling OMIM DCA, ask for supervision. Watch someone experienced before you try it yourself. Universities and labs often fall into the trap of letting unofficial habits replace clear rules—stick to what the safety data says instead. Routine training helps keep everyone on the same page and refreshes habits as new risks pop up or protocols change.

Investing in Good Practices

Storing and handling OMIM DCA the right way protects your health, the workplace, and the environment. This isn’t just about regulations; it’s about setting up a lab culture where people watch out for themselves and each other. Respect for the material, clear labeling, and using the right equipment make all the difference. Stumble once, and you learn fast why the details matter.

The Real-World Value of Purity in Chemical Purchases

Anyone who’s ordered specialty chemicals for research or industrial work knows the stakes tied to product purity. With 1-octyl-3-methylimidazolium dicyanamide—a compound widely used in catalysis, extraction processes, and electrochemistry—these stakes rise even higher. A lab trying to optimize a battery won't get far if contaminants skew experimental results by introducing variables that don’t belong. Same story for synthetic chemistry, where small differences create big headaches.

What Purity Levels Actually Arrive in the Box?

From major suppliers, you’ll usually see quoted purities of 97% or 98%. This number means that for every 100 grams you order, only a couple grams (at most) are things you didn’t pay for. These trace impurities can include residual solvents, unreacted imidazolium salts, or minor by-products from the synthetic process. Some sources market a premium 99% grade, but the difference between 97% and 99% might seem subtle until a project goes off track. Industries using this ionic liquid in sensitive roles—such as engineering advanced batteries or conducting fundamental research—tend to demand the highest purity possible. For routine separation or less-sensitive applications, the standard grade works just fine.

What’s in the Specification Sheet?

Suppliers list more than just purity. Moisture content stands out, because water in an ionic liquid drastically shifts its physical and electrochemical properties. Some producers guarantee water content under 0.5%, and a good supplier gives you a Karl Fischer titration value right up front. Typical specifications will also flag halide content (such as chloride less than 500 ppm), which can act as a silent saboteur in electronic or catalysis work. A certificate of analysis often details heavy metals and other residuals. This information separates serious vendors from mystery-batch offers.

How Do Buyers Make the Most of Their Purchase?

It’s easy to ignore the fine print on a product page. Yet the difference between a compound that’s “good enough” and one that’s truly pure often decides whether a chemistry team hits publication—or hits a wall. From personal experience, labs that rely on low-purity material tend to run repeated troubleshooting experiments, wasting both money and energy. Real trust builds over time with vendors who don’t cut corners and who offer detailed specs for every batch. Even for cost-conscious buyers, reviewing test data before every purchase prevents bigger headaches down the road.

Navigating Pitfalls and Seeking Solutions

Few issues frustrate more than untrustworthy chemicals. One way forward calls for requiring batch-specific certificates of analysis. Transparency in supplier relationships—shared data, open communication on batch changes, and clarity about shipping storage—pays off in quality control. For companies or universities new to purchasing ionic liquids, I recommend building a shortlist of vendors known in the scientific community for consistency.

Some leading brands also provide detailed spectroscopic data, including NMR or mass spec, as part of their delivery. This extra layer of assurance narrows the risk of surprises. Investment in a small benchtop instrument for routine checking (even a portable moisture analyzer) can serve as insurance, particularly for labs where results need to stand up to publication scrutiny.

Why Purity Isn’t Just a Number

Every decision around chemical quality reflects hard-earned lessons. Labs save time and protect budgets by tracking every variable, starting with the raw materials. While a two-percent impurity level can sound trivial, those little extras decide whether projects soar—or stumble. Success grows from the details, and getting the right specification puts that success within reach.