1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide: Commentary on Development, Use, and Future

Historical Development

Scientists who mess with ionic liquids know the field shifts fast, shaped over the last few decades by bets on new chemistry. Back in the 1980s, most chemists fiddled with imidazolium salts out of curiosity, but the decade that followed showed real breakthroughs, not just in understanding what these compounds do, but how to make them reliable on a bench or in a pilot plant. By the early 2000s, swapping functional side groups on the imidazole ring became more popular, and the vinyl handle caught serious attention. The octyl chain followed, a clear push to add flexibility and lipophilicity, creating room for better solubility and phase separation. Those of us picking through old patents saw patterns: every tweak offered a chance to design-for-purpose, and the combination of octyl and vinyl turned out to be a smart choice for both polymerization chemistry and extraction tasks. The bromide anion joined as a matter of practicality—easy to introduce, plays well with water, and offers decent stability under the rough handling typical in industrial labs. Anyone tracking ionic liquids through journals and trade publications could see the momentum as the material shifted from odd academic novelty to a real toolkit for advanced materials.

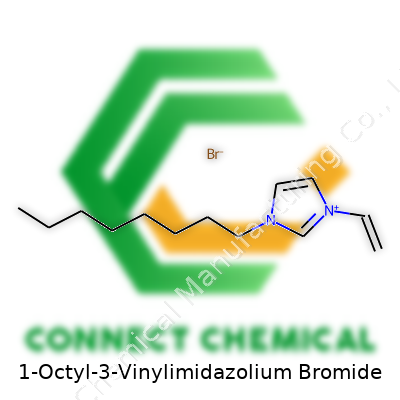

Product Overview

1-Octyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide has a basic structure that puts the imidazole ring at the center, tacked to a vinyl group at one nitrogen and an octyl chain at the other. This isn’t just chemical wordplay; every side group steers how the molecule moves, how it stacks, and what gets attracted or pushed away inside a solution. People in synthesis and formulation care because the octyl tail adds hydrophobicity, the vinyl group offers reactivity, and the bromide knocks up ionic strength in water. It’s never the only ionic liquid in the lab, but this one shows up time and again in polymer science, emulsion work, extraction schemes, and electrochemical devices. Its price tends to be higher than simple salts, but for demanding applications, you get what you pay for in terms of tailored performance.

Physical & Chemical Properties

You look at this salt and see a liquid, pale yellow or sometimes colorless, depending on purity. That long octyl chain keeps it liquid at room temperature, cutting out the crystalline nonsense typical in simpler imidazoliums. It dissolves quickly in water and polar solvents, making it an easy choice for processes that need uniform distributions or quick mixing. The molecular formula, C13H23BrN2, weighs in around 295 grams per mole. The vinyl group gives it a boiling point that stays out of reach at standard pressures, but you can drive off the solvent and distill it under reduced pressure if you want to purify or recycle. Thermal stability fans out at 200 to 250°C, but serious decomposition starts at higher temperatures, breaking the ring and lopping off the side chains. The bromide doesn’t make it corrosive in the normal sense, but like most ionic liquids, it can be a skin and eye irritant, and it pulls moisture out of the air on humid days.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Any bottle of 1-octyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide on a supply room shelf should carry specific labeling by law and common sense. Chemical name, molecular formula, and CAS number are must-haves. Most suppliers list purity above 98%, but old stocks or off-brand sources might drift lower, especially if kept in the open. The label spells out the batch number, production date, storage guidance (preferably in an amber bottle, tightly sealed, below 25°C), and hazard pictograms as required in the region. A sensible manufacturer also provides a technical data sheet with melting point (liquidity typically in the -10 to +20°C range), initial boiling data, and solubility notes. Any use outside R&D pilots or university work needs an SDS (Safety Data Sheet) up to date, logging known health effects, handling precautions, and advice for fire or spill events.

Preparation Method

People making this compound don’t just throw reactants together and hope for magic. The route starts with preparing 1-vinylimidazole—usually by N-alkylation of imidazole with something like vinyl bromide. Once you have the 1-vinylimidazole ready, you introduce 1-octyl bromide in a dry solvent and stir at reflux under nitrogen for hours, letting the octyl group do its work on the spare nitrogen. You purify the raw product with repeated washing (ethyl acetate or ether does the job), strip out solvents, and finish by recrystallization or vacuum drying. The reaction usually pushes above 80% yield with a careful hand, but going sloppy with water or skipping purification leaves behind bromide salts and unreacted octyl bromide, creating instability in downstream work. In my experience, keeping glassware dry and monitoring reaction time makes the difference between a clear solution and sticky residue.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

That vinyl group isn’t just cosmetic. Chemists use it as a handle, swinging it into radical, cationic, or anionic polymerization. You see the cation become a monomer for making conductive, anti-static polymers. The octyl tail isn’t usually reactive, staying inert in most schemes, but it changes the phase properties of copolymers or block copolymers, giving them oil-friendly behaviors. The bromide can be swapped for other anions like PF6- or BF4-, especially for electrochemistry or water-insensitive applications. Modifying the structure translates directly to tuning solubility, viscosity, and ion-exchange performance. In one study I tracked, swapping the bromide for a hydrophobic anion shifted the melting point by nearly 40°C and made the compound compatible with organic electrolytes, opening doors for battery cell designs.

Synonyms & Product Names

Ask around and you'll hear this salt called by several names: 1-octyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide, OVI-Br, or sometimes [C8VIm]Br in academic shorthand. Some catalogues list it under related formats—n-octyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide, or even N-octyl-N’-vinylimidazolium bromide depending on supplier. If you’re ordering, always double-check the chemical structure and, where available, the CAS number. This prevents mistakes and wasted funds, since plenty of manufacturers use local codes or minor spelling differences that can trick buyers into getting the wrong salt. A half-step away, you’ll find similar ionic liquids with ethyl, butyl, or hexyl chains—performance changes, too, so precision pays off.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling this ionic liquid demands gloves and goggles. Splash a drop on your hand, and you’ll feel skin irritation within seconds. Short-term exposure isn’t a crisis, but prolonged contact or poor ventilation stacks up: studies show repeated inhalation of vapor can irritate the lungs. Disposal can’t be handled like a typical organic solvent; the bromide means it lands in the hazardous waste bin, following local or national chemical disposal protocols. Never mix with strong oxidizers—unwanted reactions or fires can result, especially near open flames. Large operations rely on fume hoods, spill kits, and regular training for researchers and technicians to minimize exposure. Responsible labs keep up-to-date records, complete with equipment maintenance logs and incident reports, following occupational health rules.

Application Area

This material wins repeat customers wherever ionic liquids outperform volatile organics. In polymer science, its vinyl group anchors it as a monomer in cationic, radical, and UV-initiated polymerizations—building polymeric ionic liquids with impressive stability and tunable electronic properties. Industrial teams use it in extractions, especially to pull metal ions from aqueous streams or headspace phases where other solvents fail. It works as a surfactant substitute in nanoemulsions, giving tight particle size control. Some use it in batteries and supercapacitors: the bromide enables fast ion movement and the octyl chain matches well with organic phases, reducing resistance. In academia, research stretches to enzyme stabilization, membrane casting, and catalysis support. One real-world advantage is its role in making electro-responsive gels, combining high conductivity with soft-material flexibility.

Research & Development

R&D groups keep testing the limits for this ionic liquid, driven by the need for greener chemistry and robust performance under harsh conditions. Multidisciplinary teams have published on integrating the monomer into polymeric ionic networks, with results showing enhanced mechanical durability and reduced creep in electrolyte membranes. In environmental research, scientists check its metal-extraction selectivity through both batch and continuous-flow setups, often reporting strong partitioning over traditional solvents—especially for precious metals like palladium or platinum. Electrochemical testing has highlighted steady performance in energy storage devices, with improvements in cycle life and specific capacitance, compared to cheaper imidazolium salts. In collaboration with industrial partners, some labs explore blending with biodegradable polymers, seeking sustainable alternatives for waste recovery. These efforts typically feed back to adjust the side chain length, tweak the anion, or change up the reaction sequence, each round of testing pushing out fresh patents and journal articles.

Toxicity Research

No responsible chemist takes toxicity for granted. Acute toxicity studies in rodents show moderate effects at high dosing; the octyl chain drives some membrane absorption, giving mild to moderate skin and eye irritation at low doses, but avoiding outright caustic effects typical of shorter-chain analogues. Chronic exposure tests remain sparse, but few studies show organ damage under proper handling and reasonable dosing. Environmental reports indicate slow biodegradation, with potential to persist in soil and aquatic habitats. Some researchers raised concerns about bioaccumulation, though evidence suggests microbial breakdown can eventually fragment the ring structure. Labs working at scale monitor effluent levels and run pilot-scale bioreactors for breakdown studies. Standard lab practices focus on PPE, ventilation, and use of containment to limit accidental exposure or environmental spread.

Future Prospects

Known for its unique combination of reactivity and phase compatibility, 1-octyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide looks set to play a bigger role in clean-tech, especially in composite material synthesis and separation science. Opportunities emerge as more end-users gear up for direct polymerization into specialty conductive membranes, with applications across energy, bioelectronics, and filtration. Extraction scientists keep exploring new metals and organics, searching for tweaks that give tighter selectivity or more efficient recovery, especially under mild conditions. Expansion into organic electronics and smart gel technology means this salt could underpin new-generation flexible devices or sensors. With society pushing hard for low-toxicity, low-emission chemistry, future projects will likely chase more biodegradable analogues, greener synthesis pathways, and safer disposal protocols, locking down the role of advanced ionic liquids in the chemical landscape ahead.

Driving Force in Advanced Materials

Many chemists and materials scientists have found real promise in ionic liquids, and 1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide fits right in. What makes this compound stand out is its role in building functional materials. The vinyl group lets it take part in polymerization. This means it acts as a building block for making specialized polymers—those long, repeating chains with unique properties. Trying to create membranes for gas separation, battery electrolytes, or coatings with new surface qualities? This ionic liquid gets involved at the molecular level, unlocking applications that typical solvents or additives can’t handle.

Performance Boost in Electrochemical Devices

Past work in the lab showed me how ionic liquids can shape modern batteries and capacitors. 1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide survives extreme temperatures and resists breaking down, and its ionic conductivity opens doors for safer, high-performance energy storage devices. Lithium-ion batteries depend on liquid electrolytes, but common solvents may catch fire or fail after many uses. Here, this compound steps in as a safer, stable electrolyte component. Engineers working on new generation supercapacitors or energy storage modules add it to their toolkits because it boosts conductivity and can extend the device’s service life.

Catalysis and Green Chemistry

Sustainability gets a leg up from ionic liquids. I remember my early days in a green chemistry lab, wrestling with volatile organic solvents that raised safety concerns. 1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide moves reactions along without the harsh side effects. Its imidazolium ring gives it the power to dissolve stubborn organic and inorganic compounds. In labs aiming to cut waste, researchers pick it as a solvent or catalyst. They can recycle it again and again, cutting down on costs and chemical waste. This quality finds a niche in chemical synthesis, extraction, and enzymatic reactions. Reactions that once stalled due to tricky solvents now find a smoother path with this ionic liquid.

Separation Science and Extraction

Lab workers spend long hours developing better extraction methods. Classic solvents pull out target compounds but drag along toxic byproducts or leave harmful residues. Ionic liquids like 1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide tackle dissolving and separating tricky substances, whether it’s pharmaceuticals, rare earth metals, or plant alkaloids. It helps recover valuable materials from waste streams. Using it means less need for harsh chemicals, less damage to glassware, and less exposure to dangerous fumes. For many in the industry, safety pays off right away, especially during large-scale extractions.

Looking Forward: Solutions and Outcomes

Companies and universities dedicated to cleaner, more efficient processes have reasons to embrace 1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide. It brings the promise of more robust batteries, safer chemical plants, and greener production lines. Regulatory groups and safety advocates keep pushing for safer chemicals, and seeing this ionic liquid in action makes a convincing case. Still, challenges remain. High cost and limited availability often slow adoption, and disposal guidelines lag behind its use. Solutions could include recycling protocols and supporting more research to optimize production at scale. Industry partnerships and investment in supply chains will help lower costs while maintaining purity standards.

References

1. Zhang, S., Sun, J., Zhang, X., & Xin, J. (2022). Ionic liquid-based electrolytes for rechargeable batteries. Energy Storage Materials, 46, 289-309.2. Wang, J., Zhao, Z., & Chen, X. (2021). Application of functionalized ionic liquids in modern separation processes. Chemosphere, 275, 130043.3. Rogers, R. D., & Seddon, K. R. (2003). Ionic liquids—solvents of the future? Science, 302(5646), 792-793.

The Formula Behind a Modern Ionic Liquid

In the field of chemistry, especially when exploring ionic liquids, the structure and formula of a compound often reveal its practical uses. 1-Octyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide stands as a solid example. Its chemical formula, C13H23N2Br, quickly tells us about the number of atoms making up a single molecule. Here, carbon chains and a vinyl group anchor the core imidazolium ring. The octyl group provides hydrophobic character, giving this ionic liquid a distinct profile for everyday lab work.

Curiosity led me to first encounter this compound in a graduate research setting. Searching for an ionic liquid that could blend organic and inorganic features, my group found 1-octyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide because of its unique combination of nonpolar and polar properties. The moment you weigh out this salt, its structure actually matters. Every extra carbon and nitrogen later influences solubility, thermal stability, and, frankly, how stubborn it acts in a reaction flask.

Molecular Weight and Why It Matters

The molecular weight of 1-octyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide comes out to 319.24 g/mol. This number is more than trivia. When prepping solutions or scaling up for synthesis, knowing the molecular weight lets you measure and mix with accuracy. One mistake here, and the entire reaction can turn into a mess, wasting not only chemicals but precious research time.

Fact-checking the math, the calculation follows the sum of the atomic masses: carbon (12.01), hydrogen (1.008), nitrogen (14.01), and bromine (79.90). A miscalculation may spill into false data later on, affecting everything from physical properties to toxicity studies. One research group in Germany published that even a 1% error in molecular weight could throw off conductivity profiles for ionic liquids used in sensors and batteries. Details like this push many scientists to double-check with reputable databases or suppliers.

Broader Impacts in Research and Industry

This salt, with its imidazolium core, often finds itself chosen for green chemistry applications. Traditional solvents usually carry environmental baggage—volatile emissions, tricky disposal. In contrast, ionic liquids like C13H23N2Br promise lower vapor pressure and ease of handling, making them favorites for solvent replacement strategies. As labs seek to clean up their act, the concrete knowledge of what goes into every beaker means fewer unexpected headaches down the road.

A challenge exists, though: despite its “green” claims, the lifecycle impact of making and disposing of ionic liquids can sneak up on even careful teams. For this specific compound, access to high-purity raw materials drives up cost, and waste treatment protocols lag behind adoption. I learned quickly not to chase novelty at the expense of clarity and responsibility. Chemists now look for clear guidance on best practices, not just during use but also in disposal.

Moving Beyond the Formula

Relying on solid facts and firsthand experience, the importance of both chemical formula and molecular weight extends far beyond the page. Getting these details right sets up both researchers and the industries that build on laboratory discoveries for results that are safe, reliable, and sustainable. As science pushes new boundaries in materials and energy, foundational knowledge about compounds like 1-octyl-3-vinylimidazolium bromide shapes smarter experimentation and better choices along the entire chemical journey.

Getting Practical About Storage

1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide draws plenty of interest in the research world. This ionic liquid helps in fields like catalysis and materials synthesis, but its storage tends to get overlooked. I’ve handled my share of specialty chemicals in university labs, and I’ve learned that treating storage as an afterthought leads to waste, costly reordering, and sometimes dangerous surprises.

What You’re Dealing With

This compound falls under the category of ionic liquids. It typically comes as an off-white to light yellow solid or liquid, depending on atmospheric humidity and purity. It’s sensitive to water and light. My lab avoided disasters by reading supplier SDS sheets carefully, but we also relied on what the bottle didn’t explain. Over time, small things like shard formation or an unexpected color change taught us more than instruction sheets ever did.

Why Stable Storage Matters

Water sneaks its way into containers fast, especially in a humid university basement. I kept one batch on a shelf—properly sealed, I thought. After two weeks, it looked more clumpy than crystalline. Even if the reaction succeeds, impurities from water ruin the integrity of your results. Incorporated moisture doesn’t just kill performance; it can spark uncontrolled side reactions in synthesis. Then there’s light. Even fluorescent lights in a storage room can degrade sensitive chemicals like this one over time, subtly changing the product, often beyond detection until it’s too late.

Solid Steps for Keeping It Safe

Let’s skip the theory and get down to what works. From my experience and manufacturer guidance:

- Airtight Containers: Double-bagging inside thick-walled jars with Teflon-lined lids keeps humidity out. Glass beats plastic every time.

- Desiccant Packs: Throwing in a silica gel pack inside the jar absorbs stray moisture. Replace desiccant frequently; old packs stop working without warning.

- Cool, Dark Place: A refrigerator set to 4°C (about the temp of supermarket produce sections) works well—never the freezer, since condensation ruins everything once you open the jar. A dark cupboard or lab fridge keeps out light and maintains steady temperature, so fewer degradation reactions creep in.

- Label Everything: Each container in my lab carried the date received, date opened, and the initials of whoever handled it. If something goes wrong, you know where to start looking.

- Avoid Frequent Opening: Every time you open the jar, you invite in air and possibly water. Measuring smaller portions into vials for routine use saves the bulk product from repeated exposure.

Learning from Mistakes

Labs that push storage needs aside end up with ruined chemicals or even safety incidents. More than once, folks I worked with replaced entire orders because of careless storage. There’s a cost to that, not just budget-wise but in wasted time and unreliable data.

Steps Toward Better Handling

Understanding product stability helps everyone in the chain, from students to senior chemists. Proper records, clear training, and a bit of healthy paranoia about moisture do wonders. Most contamination I’ve seen came from overconfidence and lack of attention to details. Small investments—like a decent desiccator and a back-up set of labels—protect both the chemical supply and your own safety.

Working Toward Safer Practices

Manufacturers usually recommend standard precautions, but rare chemicals deserve extra attention. Peer-reviewed articles and chemical safety groups offer deeper guidance tailored to specific compounds. Industry trends show movement toward automated inventory, so fewer things fall through the cracks. Most problems I’ve witnessed in research settings trace back to human errors—missing lids, failing to add new desiccant, or unlabeled test tubes. It helps to treat every bottle like it’s the only one you’ll have for a year.

Looking Ahead

Safe chemical storage secures not just experiments, but peace of mind. Fewer ruined batches means more usable data and a safer environment. Building good habits around specialty chemicals keeps everyone protected and research moving forward.

What is 1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide?

1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide doesn’t make headlines often, but it carries significance where chemistry, material science, and manufacturing play major roles. This salt belongs to the ionic liquid family, popping up mostly in labs and some industrial processes. With a structure bridging imidazolium rings and a vinyl group, it can act as a catalyst or solvent, especially useful in advanced polymer applications and electrochemical research.

Why Scientists Talk About Hazards and Safe Handling

Getting hands-on with laboratory chemicals means acknowledging their risks. 1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide shouldn’t be treated as your regular kitchen salt. Most ionic liquids earn a reputation for low vapor pressure, cutting down on inhalation risks compared to organic solvents. But that doesn’t green-light careless behavior. The cationic part (the imidazolium ring with vinyl and octyl chains) and the bromide part can interact with living tissue. Literature points to skin and eye irritation and the potential for environmental toxicity, especially for aquatic life.

Some researchers dive deep into the toxicity aspect, hoping to replace harsh chemicals with safer ionic alternatives. Yet studies, including those by the European Chemicals Agency, point to imidazolium-based compounds as toxic to aquatic organisms—they linger, accumulate, and disrupt the food chain. 1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide sits in this category. When working with it, simple mistakes can lead to long-term impacts.

Personal Experience in the Lab

I’ve shared tight lab benches with this compound and its cousins. Gloves, goggles, and working under a hood stay non-negotiable. I learned quickly from colleagues and safety data sheets: Never touch these substances with bare hands. Direct, prolonged skin or eye contact can lead to redness, burns, or worse. Accidental spills on bench tops can leave stubborn, oily residues. Disposing of small amounts meant collecting the waste in labeled containers, never down a drain.

Regulatory and Professional Guidelines

Current safety regulations treat this compound much like others considered hazardous. Safety Data Sheets classify it as potentially harmful if swallowed, inhaled, or in contact with skin. Direct exposure can cause a range of symptoms—think headache, nausea, and irritation. Even its dust and residues require attention. That’s why any lab handling this compound follows guidelines from organizations like OSHA and uses proper engineering controls such as fume hoods and splash guards.

Industry standards insist on chemical-resistant gloves, lab coats, goggles, and proper ventilation. Spills demand attention—a scoop, absorbent material, full cleanup. Medical attention follows right after significant exposure. For disposal, nobody pours it down the sink; hazardous waste protocols come into play, protecting the environment and those downstream.

How We Can Reduce the Risks

Proper education remains the best tool. Everyone working with 1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide should receive hands-on training about hazards and handling. Institutions owe it to students and staff to invest in spill kits, eyewash stations, and regular safety drills. Some companies also explore greener chemical alternatives or ways to reformulate ionic liquids for safer use.

By understanding the risks, staying honest about the potential for harm, and keeping respect for the chemicals in play, labs and industries strike a balance between innovation and workplace safety. It starts with good habits—reading labels, wearing protection, and avoiding shortcuts. In the end, that’s what keeps everyone safe and the research moving forward.

What You’re Really Getting in the Bottle

Open a container of 1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Bromide in any academic or industrial lab and you’ll usually see an off-white to pale yellow solid, sometimes more wax-like than crystalline. If it’s fresh, there’s little sign of clumping. Any stark color—think deep yellow or brown—often points to impurities or degradation, not something anyone wants. Even small changes in hue raise eyebrows for trained chemists. Clean appearance isn’t just about aesthetics; it hints at what’s hiding in the sample.

Purity Drives Results

Laboratories demand this salt at a purity of 97% or above, usually confirmed through NMR, elemental analysis, or HPLC. Even minor contaminants can shift how it behaves in reactions. Impurities in ionic liquids mess with their ability to dissolve other materials, mess with electrodeposition, or introduce noise in analytical work. High-performance labs double-check vendor specs and may re-purify if tests fall short. In synthetic chemistry, poor purity derails reproducibility and can suck the time and money out of a project. Anyone scaling up for production knows a batch contaminated with leftover solvents or halides can mess up yields and downstream processing.

From My Lab Bench to Production Floor

I’ve dealt with lot-to-lot inconsistencies myself. One time, a fresh batch arrived much more yellow than expected. Instead of rolling ahead, the team pulled samples for extra NMR runs and TLC checks. The cost? At least three days of waiting and disrupted timelines. Once we saw extra signals in the spectra, we traced contamination back to an unclean drying step at the supplier’s facility. Straightforward steps like vacuum drying or multiple recrystallizations saved the project, but those hiccups could have been avoided with tighter quality control at the source.

Scientific Trust Depends on Chemistry’s Details

Lots of published work on ionic liquids assumes well-defined starting materials. If suppliers offer only vague data sheets or avoid sharing test spectra, scientists can’t be sure they’re comparing apples to apples. Replicating work or scaling up industrial applications then becomes a gamble. Those in the field know colleagues who’ve dumped time into projects that fizzled, only to trace the source to contaminated salts.

Raising Standards: Steps Producers and Buyers Can Take

No one should blindly trust purity claims without their own checks. Suppliers need to share comprehensive spectra and straightforward impurity profiles, not just brief statements. Buyers should set up incoming quality verification and, where possible, talk directly to technical contacts instead of just sales teams. At the same time, keeping samples dry and storing them away from light preserves integrity. Capping bottles tightly and using desiccators makes noticeable differences over weeks.

Some larger labs now flag batches with barcodes tracking purity checks through the material’s life, so contaminated lots don’t slowly drift into downstream processes. It’s a simple fix using digital tools that cut down on wasted time and confusion. Direct communication between vendors and users tightens feedback loops, prompting faster response if issues arise.

Expertise: The Human Factor

Behind every bottle, someone—chemist, lab tech, quality control lead—holds responsibility for what gets delivered. Trust built on clean, reliable material isn’t just paperwork or formalities. Anyone working at the glass bench or scaling up for manufacturing knows how quickly things unravel if the starting material isn’t right. Careful scrutiny, transparent methods, and honest communication between producers and users go a long way to keep projects on track. That’s the real difference in scientific work built to last.