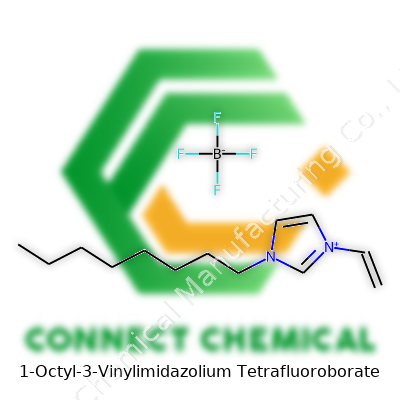

1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate: A Deep-Dive Commentary

Historical Development

From my own experience following chemical innovations through the late twentieth century, the arrival of ionic liquids like 1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate occurred around a surge of interest in green chemistry during the 1990s and early 2000s. Chemists searched for alternatives to volatile organic solvents, leaning on ionic liquids because they generally vaporize much less and reduce pollution. Several research groups, motivated by the push to develop more sustainable industries, extended the family of imidazolium-based salts. The addition of vinyl and octyl groups set the stage for further customization, encouraging adaptation beyond simple solvent replacement. Looking at early patents and journal articles, pioneers detailed the upgrades these modifications gave to both the stability of the materials and their reactivity in all sorts of organic syntheses. Unlike older halide-based precursors, this compound made new polymer and catalysis applications possible due to the special chemistry at its core.

Product Overview

1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate combines an imidazolium ring (a mainstay in ionic liquid chemistry) with a vinyl group for polymerization and an octyl chain which helps modulate solubility and viscosity. The tetrafluoroborate anion balances the whole, lending further chemical stability and moderating the reactivity in moisture-laden environments. I’ve seen chemical suppliers tout this compound as a standout ionic liquid for electrochemical uses, but its applications often spill far beyond into catalysis, materials processing, and certain niche areas of separation science. The vinyl function sets it apart from non-polymerizable counterparts, opening pathways into polymer science and novel composite materials. Its unique qualities put it atop lists for researchers chasing new properties in ionic liquid engineering.

Physical & Chemical Properties

From handling similar imidazolium salts in the lab, 1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate generally appears as a pale to colorless oily liquid, odorless with a medium-high viscosity compared to shorter-chain relatives. It shows considerable thermal and (importantly) electrochemical stability, holding up between minus twenty and about two hundred degrees Celsius without breaking down in most common laboratory settings. Hydrophobicity increases with the longer octyl chain—meaning it resists dissolving in water and favors organic solvents. Its ionic nature makes it a poor conductor of heat but an excellent medium for ionic conduction, which suits certain battery and sensor roles. The non-coordinating and weakly basic tetrafluoroborate anion cuts down on interference in catalytic cycles, letting the cationic part take the lead in guiding chemical reactivity. Handling its physical quirks during scaling, I’ve seen viscosity management cause real headaches, and sticker shock for larger synthesis runs is genuine, given the specialty reagents needed to build both the cation and the anion.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Product sheets typically lay out the necessary grading, purity levels (often at least 98% by NMR and elemental analysis), and precise water/acidity content since even small impurities muck up sensitive processes. Labels show chemical formula (C15H27BF4N2), molecular weight (338.20 g/mol), and standardized identifiers such as CAS numbers and EC numbers for supply chain tracking. Packaging follows the rules for moisture opposition, usually glass bottles or high-density polyethylene containers sealed against humidity. I have seen labs get burned by overexposure to air during sampling, as ionic liquids like this one grab water from the air, altering intended properties. Manufacturers should provide certificates of analysis and storage guidance, and batch numbers help trace any issues over time.

Preparation Method

Preparation starts with the quaternization of 1-vinylimidazole using octyl halide under carefully controlled conditions—usually anhydrous solvents and exclusion of light and air. This step often takes several hours at moderate temperatures, with the progress monitored by proton NMR. Once formed, the halide salt undergoes metathesis by mixing with sodium tetrafluoroborate, which, through a simple ion exchange, yields the final product. This salt washes with water to strip away impurities, then gets dried in vacuo. From experience, full removal of unreacted starting materials makes or breaks product performance since trace halides or organic contaminants kill both polymerization control and electrochemical utility. Labs using this material for synthesis projects obsess over purity because side reactions from unwanted contaminants can derail months of planning and data collection.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The vinyl group in this molecule opens doors for direct polymerization—think photopolymerization, radical, or ionic methods—enabling formation of polymerizable ionic liquids (PILs) and related networks. I’ve worked on ionic hydrogels where the vinyl handle lets you ‘graft’ or network the imidazolium salt straight into the polymer backbone, lending unique ionic conductivity and mechanical strength. Chemists sometimes tweak the alkyl chain length or swap the BF4- for other anions to tailor solubility or charge distribution. The vinyl group also invites click chemistry extensions or Diels-Alder adduct formation, dramatically expanding the utility for advanced materials. Being able to attach this compound onto surfaces or link it with nanomaterials changes its role from just a solvent to a part of the material itself.

Synonyms & Product Names

Chemical suppliers and academic papers list this compound under a variety of names. You’ll see 1-octyl-3-vinylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate as the main listing, but variations like vimiBF4, [OVIm][BF4], and even 1-octyl-3-ethenylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate pop up, especially in patents. For ordering or regulatory purposes, the exact structural identifiers—such as SMILES or InChI—help clarify any ambiguity, since naming errors have led to supply mishaps in more than one lab.

Safety & Operational Standards

Working with ionic liquids like this demands attention to toxicity, fire safety, and environmental exposure. Tetrafluoroborate salts occasionally liberate corrosive hydrogen fluoride if they break down in moist or high temperature conditions, which pulls strict storage and disposal guidelines into play. Gloves and goggles remain the baseline; working with a fume hood and having HF antidote kits nearby goes beyond caution—it’s about not taking risks I’ve seen others regret. Local regulations sometimes classify ionic liquids as hazardous materials based on aquatic toxicity, which limits large-scale disposal and calls for dedicated waste collection. Manufacturers publish SDS sheets that explain reactivity, exposure limits, and safe handling in clear terms. Shipping gets limited by both quantity and temperature; I’ve known delays and paperwork snags as these materials move across borders because one mislabel could freeze an entire batch in customs.

Application Area

Uses for 1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate run deep: advanced batteries, supercapacitors, antistatic coatings, and special catalysis spring to mind. In my time supporting polymer physics projects, I’ve watched these materials power new generations of solid-state electrolytes and ionic conductive films. Electrochemical researchers chase pure conductivity and high chemical stability; the polymerization possible here brings added structure and mechanical reinforcement in devices like actuators and sensors. The unique hydrophobic/hydrophilic duality—thanks to its octyl tail—lets it extract or separate compounds in ways neither classic ionic liquids nor ordinary solvents manage. Environmental remediation, rare metal recovery, and organic synthesis all see active exploration, usually driven by governmental grants wanting safer and more selective processing.

Research & Development

Research labs stay busy tuning the structure–property relationships of imidazolium ionic liquids. The vinyl feature lets scientists craft wholly new polymer architectures, blending ionic conduction with flexibility. Collaborations between chemical engineers and material scientists lead to composite membranes and new actuator materials—devices that bend or move in response to electric fields. Startups target ionic liquids to reduce toxic waste from extractions (like in critical metals), while academic centers probe catalytic cycles cleaner and faster than before. Even high school outreach programs sometimes include ionic liquids to show students the future of green chemistry, since handling these clear oils appears less menacing than old-school solvents.

Toxicity Research

Ecotoxicity and human safety raise concerns with any novel chemical. Early studies on imidazolium salts revealed moderate aquatic toxicity, particularly as the hydrophobic chains lengthen, pointing to bioaccumulation as a problem if larger spills or chronic use go unmanaged. Scientists have published data on cell viability, genotoxicity, and skin sensitivity, revealing that the toxicity profile ties closely to both the side-chain structure and the nature of the counterion. I recall reading about the unexpected behavioral changes in zebrafish at concentrations well below those found in manufacturing settings—reminders that small molecules can ripple through ecosystems. Regulatory agencies push for more rigorous, long-term assessment protocols as production of ionic liquids accelerates.

Future Prospects

Interest in 1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate continues climbing, driven by the pursuit of safer, more efficient energy storage, environmentally benign extraction, and adaptable polymers. Juniors in my lab speculate about embedding these compounds in flexible electronics for wearables and soft robotics, while funding bodies prioritize research promising reductions in solvent waste. Scale-up challenges—cost, purity control, regulatory hurdles—will require joint effort from academia and industry. Rising focus on circular economies means future designs could aim for easier recovery and recycling after use. All signs point toward a growing role for ionic liquids like this, especially as global industries chase both high performance and sustainability.

Diving Into Molecular Identity

I’ve always believed that chemistry has a funny way of showing off its elegance in the simplest formulas. Take 1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate, for instance. Its structure may look like a mouthful at first, yet once you break it down, each part tells a practical story. The chemical formula for this ionic liquid is C15H27BF4N2. That’s the stacked-up tally of each atom making up this compound.

What Goes Into This Ionic Liquid

Breaking down the name: You start with imidazolium, a ring built from carbon and nitrogen. Add an octyl group—a straight chain of eight carbons—onto one nitrogen. Next, bolt on a vinyl group—two carbons double-bonded at the other nitrogen. That’s your cation sorted out: pretty versatile, and already showing off some demand in research labs that focus on electrochemistry and green chemistry projects. The other piece, the anion, comes from tetrafluoroborate (BF4). This negative ion balances the positive charge, lending the compound its unique set of capabilities.

Why the Formula Steps Up in Research

I’ve seen this kind of molecule pop up in more academic papers over the last ten years. Ionic liquids stand out for their low volatility and thermal stability. So, people handling batteries or solar cells reach for compounds like C15H27BF4N2. The octyl tail gives the molecule flexibility in dissolving or blending with organic materials. The vinyl group means researchers dream up new applications, like polymerization reactions or surface modifications. In essence, the formula isn’t just a static string of numbers and letters; it acts as a blueprint for clever ideas in advanced materials.

Real-World Impacts and Safety

No one wants to ignore the health and environmental impacts of ionic liquids. Early on, folks thought all ionic liquids were inherently “green.” That’s not always true. Tetrafluoroborate-based salts sometimes break down under extreme conditions and could let out toxic fluorides. Paying attention to safety data sheets and proper disposal instructions matters. Labs switching from traditional organic solvents to ionic liquids like this one still need to tackle waste management head-on. Ignoring these considerations just passes the problem along to the next technician—or worse, into the water supply.

Looking Past the Beaker

I’ve watched this compound, and others like it, inch their way into more practical technology—especially in batteries and electroplating. Research sometimes outpaces marketplace readiness. High cost and uncertain sourcing can slow industrial rollout. Building local supply chains, recycling ionic liquids, or even designing easier-to-recover versions will drive broader adoption. Even as the formula seems static on paper, the real-world footprint depends on choices made in production, laboratory practice, and eventual recycling.

Better Chemistry Through Collaboration

The formula for 1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate isn’t just academic trivia—it sits at the meeting point of hope for sustainable technology and practical caution. Chemists, engineers, and policy makers have a shared challenge: unlock the value of these new materials without repeating mistakes from outdated solvents or reagents. Knowing the formula inside out forms the first step, followed by thoughtful action at every stage of its life cycle.

Unlocking Green Chemistry’s Puzzle

Walk into any lab that cares about green chemistry, and you'll notice how every choice—every solvent, every reaction—matters. 1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, a mouthful to say, but even trickier to replace, finds a sweet spot where others fall short. This ionic liquid trades the pungent smell of volatile solvents for something far more gentle—no wonder researchers keep circling back to it. Its unique molecular structure brings together both hydrophobic and conductive properties, making it valuable where water-based systems just don’t cut it.

Electrochemistry Needs Reliable Friends

Electrochemists like myself have run through the laundry list of solvents over the years—acetonitrile, propylene carbonate, even sulfolane—trying to nudge electrons efficiently. The sticking point comes from traditional solvents’ limited voltage windows, not to mention safety headaches and environmental mess left behind. Step into the lab, set up a cell with 1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, and suddenly that window opens wide. Not just a lab quirk: the battery and capacitor industries turn to this particular ionic liquid when looking for safer electrolytes that hold voltage steady and resist flammability.

Polymer Science and Cleaner Manufacturing

As a base for polymerization, this compound lets researchers skip harsh initiators or complicated reaction routes. Its vinyl group builds right into the growing polymer chain, leading to innovative materials with unique conductivity and flexibility. Having tinkered with polymer synthesis, I've seen how this shortcut slices days off longer protocols. More and more teams combine it with advanced plastics (think: antistatic flooring or flexible displays), betting on lower toxicity and tailored electronic properties. The aversion to legacy compounds—and demand for greener, high-performance materials—keeps factories switching over, even if some may grumble at upfront costs.

Catalysis: Small Changes, Big Impact

Put this ionic liquid in a catalytic system, and the whole picture shifts. Scientists lean on it as a recyclable medium that actively stabilizes metal catalysts. Here, it's not just a bystander, either. The structure tunes reaction rates and selectivity, meaning less waste and fewer byproducts clogging up the process. On a pilot plant scale, that difference can drop disposal bills and make regulatory headaches a thing of the past. A close friend in the industry saw firsthand how swapping in ionic liquids trimmed their emission figures for EPA reporting—real-world impact, not marketing fluff.

Pharma, Sensing, and a Dash of Curiosity

Pharmaceutical work demands purity and precision—no room for slip-ups. This ionic liquid slips into extraction processes and sensor development, where it grips target molecules tighter than water or regular organic solvents. Sensors built with it handle biofluids, cleaning up signals in a way that’s tough to match. Every time a new compound crops up—be it a stubborn impurity or tricky metabolite—1-Octyl-3-Vinylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate gives analysts a fighting chance to separate and detect without tossing health or environmental safety out the window.

Paving the Way for Safer Alternatives

Every year, green chemistry pushes forward, while budgets and timelines lag behind. Products like this ionic liquid spark real excitement because they share hard-to-find traits: high conductivity, thermal stability, and minimal impact on the planet. To keep progress going, suppliers must pay close attention to long-term toxicity and recyclability. In academic and industrial circles alike, experiments show promise—emphasizing not only performance but also how waste disposal can improve. Open collaboration, transparent data-sharing, and funding for life-cycle analysis stand as the clear next steps for bringing these sustainable choices from lab bench to daily business.

References

1. Welton, T. "Room-Temperature Ionic Liquids: Solvents for Synthesis and Catalysis", Chemical Reviews, 1999.2. Rogers, R.D., Seddon, K.R. “Ionic Liquids--Solvents of the Future?”, Science, 2003.3. Endres, F., Zein El Abedin, S. "Air and water stable ionic liquids in electrochemistry", Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 2006.

Respecting Chemistry in Real Life

Most folks don’t wake up thinking about chemical storage. But anyone dealing with lab work, pharmacy inventories, or even home projects knows hazards climb quickly without respect for safety. A compound isn’t just a building block for products—it's a responsibility. Eyes, skin, lungs, water, and land don’t get a reset button after a spill or exposure. Smart storage habits and careful handling give professionals and communities the kind of protection that goes beyond checking off compliance boxes.

Start with the MSDS, Not Your Gut

For every chemical, the manufacturer’s safety data sheet (MSDS) spells out physical and health risks. Too many people skip this step, guessing at shelf placement or trusting their memory. One careless moment and the results can range from ruined equipment to poisoning. With some acids, missing the fine print about needing glass or special plastic over metal can trigger corrosion and leaks. Some powders form explosive dust clouds with the tiniest spark—an oversight I’ve seen cause real scare in a busy research setting. Rely on the MSDS and cross-check it for storage temperature, humidity, sunlight exposure limits, compatibility with surrounding products, and even the pressure in the room. It may feel like a chore, but nobody's immune to trouble if they ignore details.

Labeling, Lighting, and Location Matter

Clean, legible labels are just common sense. In my own lab, faded stickers led to confusion more than once. Relabeling everything with waterproof markers and bold warnings prevented mix-ups. Chemicals left in mystery containers or under vague abbreviations invite mistakes. The routine of keeping everyone up to date, especially during staff changes or reorganizations, really pays off.Storage shelving should never crowd materials together. Flammable liquids get separated from oxidizers. Water-reactive powders aren’t left near sinks or pipes. Eye-level shelving avoids the risk of dropping containers while reaching up high or stooping down low. Some compounds break down faster with direct sunlight—simple blackout curtains or solid cabinet doors help maintain product quality and prevent dangerous byproducts from forming.

Personal Protective Gear and Team Training

No amount of warnings mean much if staff brush off goggles and gloves. People grow used to routines and start cutting corners, but skin absorption and chemical splashes happen much quicker than folks expect. Walking through a spill drill or evacuation plan with new team members sets a serious culture early on. Supervisors who model good practices—washing up after each session, inspecting fire extinguishers, checking ventilation—set the tone for everyone else. Line workers notice these efforts and are more likely to ask questions or point out risks when they spot something off. This openness guards against silent accidents, the kind nobody sees coming until it’s too late.

Don’t Ignore Small Steps for Big Results

It all comes down to culture and diligence. Simple acts like keeping workbenches uncluttered, tightening container caps right away, or storing acids away from bases prevent mishaps more than any fancy technology. Temperature logs, humidity monitors, and even the humble reminder sticker create a safer environment. Sometimes, just double-checking where a substance fits in the chemical family chart keeps a warehouse full of products from becoming a hazard zone. No detail is too small: vigilance shows respect not just for the compound itself, but for the people nearby and the long-term safety of the workplace and surroundings.

What is This Chemical, and Where Does It Show Up?

1-Octyl-3-vinylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, usually called an ionic liquid, tends to show up in lab settings and advanced manufacturing. Ionic liquids promise less air pollution compared to some old-school solvents. Folks see them as a new way to do cleaner chemistry, but the health and safety profile is still in the early stages of understanding.

Safety Data and Health Hazards

Nothing makes me raise an eyebrow faster than a substance with gaps in the safety record. Most ionic liquids get marketed as “green,” but that label can be misleading when no long-term studies exist. Take this one—1-octyl-3-vinylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate doesn’t pop up on mainstream regulatory lists as a restricted hazard, but the fine print tells a more nuanced story.

Folks who’ve handled it in real-world labs have run across skin and eye irritation. The imidazolium part, given its structural similarity to other compounds, could pose risks once inhaled or absorbed. Toxicology reports can’t write a blank check here—one rat inhalation study with related ionic liquids pointed to lung inflammation and liver stress after repeated exposure. No full-scale studies for humans have turned up, so anyone working with the stuff should lean on gloves, goggles, and fume hoods.

Chronic toxicity still feels like a black box. The tetrafluoroborate piece can break down, especially under heat or in water, sometimes releasing boron- and fluorine-containing byproducts. Some of those, like boron trifluoride, are considered highly toxic and corrosive. Chemical burns aren’t just a chemistry-class cautionary tale; they happen in rushed labs. Making sure the space has proper ventilation and spill gear feels non-negotiable.

Environmental Impact and Persistence

I’ve talked with researchers who worry that ionic liquids don’t break down easily in soil or water. Long alkyl chains, like the octyl group here, tend to stick around. If these substances escape into the environment, biodegradable claims get shaky fast. Fish and algae take the hit; some studies link imidazolium-based liquids to interference with aquatic life growth and reproduction.

Big chemical manufacturers like BASF and Merck urge caution and suggest keeping any waste out of water streams. Waste management plans need to get in place before anyone buys a single bottle. Hoping things biodegrade on their own doesn’t work well for ionic liquids with these long chains.

Practical Solutions and Safer Use

I always tell lab newcomers: treat unknown chemicals with respect, not overconfidence. For substances like 1-octyl-3-vinylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, a thorough risk assessment before use pays off. Start with small quantities. Review the latest Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) and stay cautious around spills. Wear full PPE, avoid skin contact, and don’t breathe in vapors.

Disposal should never mean pouring it down the drain. Partner with a hazardous waste contractor who knows how to handle ionic liquids. Keep clear records so nobody stumbles into accidental exposure later.

Researchers and industry professionals keep pushing for less toxic alternatives as lab automation and sustainable chemistry progress. Until then, solid training and a healthy skepticism of “green” marketing claims go a long way for anyone who deals with these advanced materials.

Purity Matters in Every Industry

Purity often ends up as the question customers ask once they realize how much it drives cost, safety, and reliability. In my own early days working in a lab, purity wasn’t just a detail—it could be the reason an experiment succeeded or failed. Later, talking with formulators or food producers, I found the same concern echoed: purity’s a promise, not a footnote.

Typical Purities and What Drives Them

Purity levels differ depending on the use. In pharmaceuticals, 99.9% purity is the expectation for raw ingredients. Even a stray ion in a reagent can affect the chemistry of a batch. In the food sector, the numbers usually run lower, but oversight from agencies like the FDA means food-grade materials can’t carry heavy metals, pesticides, or microbial risks above set limits. Labs selling to researchers aim higher, sometimes offering 99.999% purity for the purest experience—a demand often driven by analytical methods rather than laws.

Electronics might push things even further. Semi-conductor industries measure impurities not just in percentages, but in parts per billion. That specification isn’t for show. Contaminants can create faults on a microscopic level, killing yields and costing millions. I once watched a wafer processing line come to a total halt over an impurity smaller than a dust grain.

What Sets the Purity Standard?

Price caps and supply often push companies to favor technical grades over premium purities. Yet honest suppliers publish certificates of analysis, not just numbers on the side of a bag. Without that transparency, buyers learn the hard way that not all “99%” claims mean the same thing. Years ago, my team tried to save money buying “industrial” chemicals from an unfamiliar source. We faced corrosion and contamination issues from unseen trace elements, and lost precious time tracing the issue to the source.

Certifications and independent testing keep people honest. Looking for ISO compliance or GMP standards brings peace of mind, since third parties have verified what’s actually in the drum. Reputable shops agree to full documentation, batch-to-batch traceability, and clear lists of what’s left in terms of moisture, ash, or unintended trace contaminants. Anything less should trigger red flags.

The Cost of Cutting Corners

Saving a few bucks upfront may come back to bite. Cutting purity increases the risk of downtime, product recalls, or regulatory headaches. One contaminated batch can destroy reputations. A major vitamin manufacturer once recalled thousands of bottles after learning a trace solvent exceeded legal limits, all for a minor cost saving. That episode taught everyone involved that purity isn’t just a paperwork exercise, but a core business concern.

Smart Moves for Buyers

Buyers who value reliability ask for more than a number. They look for proper audit trails, challenge ambiguous claims, and keep communication open with suppliers. Some run third-party tests on incoming batches, even though it costs extra. Knowing the difference between “food grade,” “lab grade,” and “technical grade” helps avoid surprises and keeps operations running smoothly.

At the end of the day, purity isn’t an abstract standard. Every percentage point earns its keep through less risk and more consistent outcomes.