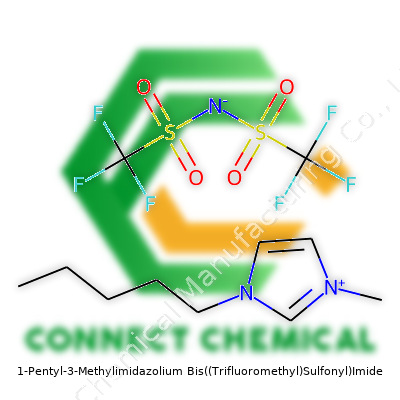

1-Pentyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide: An In-Depth Look

Historical Development

The emergence of 1-pentyl-3-methylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide, often referred to by its chemical shorthand [C5mim][NTf2], traces back to the late 20th century, during the broader quest for ionic liquids that sidestep the typical pitfalls of volatile organic compounds. Researchers around the globe noticed that traditional organic solvents caused all sorts of headaches, like environmental damage, workplace safety incidents, and mounting regulations. This compound stood out because it blended the low-melting-point characteristics of ionic liquids with remarkable stability and near-zero vapor pressure, lending itself to projects where air quality and chemical control matter most. By the early 2000s, labs began swapping in these new salts to minimize emissions in their synthesis and separation work, while tech firms eyed their potential for energy storage.

Product Overview

1-pentyl-3-methylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide combines an organic cation—1-pentyl-3-methylimidazolium—with a tough anion structure, paving the way for applications that are not just niche but transformative. You can spot it in vials with a typically colorless to pale yellow liquid appearance, usually clear and with a high viscosity. This ionic liquid promises less evaporation risk than water or alcohol, handles a range of organic and inorganic solutes, and stands up to the kind of demanding processes that most solvents wilt under. Technical and scientific communities keep turning to it when equipment corrosion or stubborn reactivity call for something tougher.

Physical & Chemical Properties

The compound sits on the heavier side, clocking in at a molecular weight of about 419.4 g/mol. It doesn’t flash off at ambient conditions, so you won’t smell much even right after pouring, thanks to its minuscule vapor pressure. The melting point typically hovers below room temperature, making it manageable without complex gear. It boasts thermal stability up to around 300°C, letting it ride out long syntheses without breaking down or releasing noxious byproducts. Its miscibility landscape covers several nonpolar and polar solvents, yet water’s a different story—while some mixing happens, you can usually separate the phases with a baffle or funnel. Researchers appreciate its electrochemical window of roughly 5 volts, making it a favorite in electrochemical research and battery tests.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Labeling requirements follow international standards, so suppliers mark every container with precise details. You’ll see the CAS number, lot identification, purity (often over 98%), manufacturing date, and recommended storage conditions. Packaging varies from amber glass bottles for small-scale lab work to fluoropolymer-lined drums in industrial shipments. Any serious player in the market sticks to rigorous quality control, providing spectroscopic signatures (NMR, FTIR) and impurity thresholds. If you’re selecting a batch for experimental or commercial use, these facts become important for both regulatory audits and reproducibility.

Preparation Method

Synthesizing [C5mim][NTf2] doesn’t require unreachable machinery, but it rewards careful technique. Typically, the process begins with the alkylation of 1-methylimidazole using 1-pentyl bromide, generating the intermediate 1-pentyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide. This salt then reacts with lithium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide in a solvent like water or acetonitrile, which induces a metathesis reaction leading to the target ionic liquid. For any lab or factory looking for high purity, repeated extractions and thorough drying remove water traces and unreacted starting materials. Labs often monitor purity using NMR, as trace contaminants like leftover halides or unreacted imidazole can skew results.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Thick with customization opportunities, the imidazolium backbone and bulky anion both accept modifications for applications that demand more from the molecule. Substituting the pentyl group with other alkyl chains changes viscosity and hydrophobicity, letting researchers tailor behavior for specific reactions or separations. The bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide anion can also swap with other large anions like PF6- or BF4-, which tweaks everything from solubility to electrochemical performance. Chemists studying catalysis, extraction, or even electroplating often tweak these ions, searching for the sweet spot between performance and practicality. The stability and resistance to nucleophilic attack make it less likely to break down, even in the presence of strong acids or bases.

Synonyms & Product Names

Expect to see this chemical named in several ways depending on the catalog, journal, or vendor. “1-pentyl-3-methylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide,” “[C5mim][NTf2],” and “1-Pentyl-3-methylimidazolium NTf2” all crop up in literature and supplier listings. Less often, suppliers will use alternative systematic names, like “1-Pentyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)azanide.” It pays to double-check registries and purity sheets; relying only on the acronym risks confusion if you’re working within groups that handle many ionic liquids.

Safety & Operational Standards

Despite its stability, safe handling isn’t just a suggestion. Direct skin contact or inhalation over a prolonged period isn’t something anyone should get used to, especially in settings where ventilation or PPE isn’t adequate. Current research finds that long-term occupational exposure to many ionic liquids can irritate skin or eyes, and animal studies report mild toxicity with repeated doses; gloves, goggles, and fume hoods play a crucial role in regular use. Waste management involves collecting residues separately from aqueous or halogenated waste streams. Environmental regulations, especially within the EU and North America, increasingly watch for improper disposal. Following SDS guidance, users keep containers tightly closed, away from ignition sources, and typically store them below 30°C.

Application Area

The versatility of [C5mim][NTf2] shines brightest in chemical synthesis, electrochemistry, and advanced material processing. In organic labs, chemists use it to replace flammable solvents in catalysis, nucleophilic substitution, and extraction—cutting the risk of fire and reducing VOC emissions. It pops up in battery research, especially in next-generation lithium-ion and beyond-lithium cell studies, where the stability across voltage swings and negligible vapor pressure trump most alternatives. Analytical chemists lean on its ability to dissolve both hydrophobic and hydrophilic analytes; they often use it in chromatography as a partitioning medium. In the world of material science, additives based on [C5mim][NTf2] improve the performance of polymers and even ionogels, proving useful for sensors, actuators, and even new medical devices.

Research & Development

The lion’s share of breakthroughs in ionic liquid science over the past decade build on the backbone provided by compounds like [C5mim][NTf2]. Researchers keep pushing its boundaries, exploring new electrodes for sustainable energy storage, advanced lubricants, or “green chemistry” synthesis pathways aimed at reducing greenhouse gas footprints. Projects in university and industry settings evaluate its behavior under extreme conditions—high pressure, varying humidity, or intense electrochemical cycling. Scientists report on each small adjustment’s effect on ionic conductivity, solvation power, and chemical compatibility. As each experiment peels back another layer, paths open for everything from less toxic process streams to electronics with longer lifespans and lower failure rates.

Toxicity Research

Early studies painted a rosy picture, promoting [C5mim][NTf2] as a friendlier cousin to petrochemical solvents. Deeper dives, though, underscore that “non-volatile” doesn’t always equal “nontoxic.” Repeated exposure in cell cultures points to moderate cytotoxicity; aquatic toxicity data suggest that spillage or disposal in waterways should be curbed. Some metabolites produced in breakdown pathways may challenge water organisms even if they’re less harmful to humans. Long-term animal studies keep raising questions about bioaccumulation. Environmental scientists recommend that industries and research outfits don’t simply rely on the “green” label, but evaluate actual risk profiles through both field tests and laboratory modeling. Rising evidence signals that precaution and mitigation remain essential, especially as these formulations become mainstream.

Future Prospects

Demand grows for solutions that drive sustainability without taking away efficiency or flexibility. [C5mim][NTf2] shows strong promise where those goals intersect. Advances in synthesis have started to whittle down costs, making the substance attractive beyond just boutique research or specialty markets. Startups and multinational firms alike investigate new uses, from environmentally tuned cleaning formulations to safer, higher-output storage solutions for renewable energy systems. Real progress hinges on ongoing studies into environmental pathways and chronic toxicity, supported by clear, tough standards from both governments and professional bodies. With every conference and publication, the roadmap for [C5mim][NTf2] widens, pointing to deeper integration in manufacturing, energy, and analytical fields—always with a sharp eye on up-to-date data and honest risk assessment.

An Ionic Liquid Making Waves

This isn’t some tongue-twister for chemistry students. 1-Pentyl-3-methylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide, known to many researchers as a “Task-Specific Ionic Liquid,” holds a solid spot in modern lab work. From firsthand experience, dealing with this substance shows just how much it can handle—nearly impossible to ignite and not likely to evaporate at room temperature. Working with it feels less nerve-racking compared to flammable solvents, and its stability stands out during long experiments.

Green Chemistry’s Favorite Solvent

Sustainability stays high on every scientist’s list. Many labs—my own included—have shifted toward solvents that leave a lighter mark on the planet. This ionic liquid steps in where old-school organic solvents struggle. Its low vapor pressure means less exposure risk. Colleagues in pharmaceuticals tell stories of improved yields for extraction and separation tasks, all while cutting back on waste and toxic emissions.

Electrochemistry and Energy Storage

The leap toward new batteries or supercapacitors depends a lot on electrolytes that serve up high ionic conductivity. I’ve watched storage researchers blend this ionic liquid into lithium-ion and sodium-ion battery prototypes, aiming to boost stability over thousands of cycles. Reports show devices running safer, handling larger charges, and sometimes even stretching past high temperatures just fine. These perks attract investment from battery startups and established energy firms.

Solving Problems in Synthesis and Extraction

Chemical manufacturing often gets tangled in problems with purity and recovery. In my circle, process chemists using imidazolium-based liquids saw better selectivity in catalytic reactions—less side-product, less mess. Separating rare earth metals, for instance, feels less like guesswork and more like precision work with this tool in hand. Environmental labs, too, scoop up pollutants using similar ionic liquids, snagging metals and organic waste from water samples without much fuss.

Applications in Biomolecular Research

Protein folding, DNA isolation, and enzyme studies count on gentle, dependable solvents. Peers describe how the ionic liquid preserves the structure of biomolecules in tricky experiments. This means less denaturing and higher confidence that results match real biology. Universities running protein engineering projects report sharper, more reproducible outcomes, especially when working with difficult natural products or hydrophobic peptides.

Azoth to Industry: Next Steps

Real progress in bringing this material to more industries requires safer handling protocols. The cost sometimes slows scale-up, and questions about environmental breakdown after use crop up among teams looking for responsible options. More studies on end-of-life disposal and toxicity can lay out clear roadmaps for chemical firms, pharmaceutical companies, and energy labs. Funding agencies should continue spotlighting projects where these ionic liquids create safer, greener, and more cost-effective systems. With real collaboration, more sectors could take advantage of the unique package that 1-pentyl-3-methylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide offers.

Ionic Liquids: Behind the Buzz

Ionic liquids have picked up a solid reputation in labs thanks to their unusual ability to stay liquid at room temperature and their promise for green chemistry. Unlike common solvents, these salts dodge many of the volatility problems. They don’t evaporate the way water or alcohols do, so accidental solvent losses stay low, which keeps both the workplace safer and the lab budget happier.

Chemical Stability: Real-World Experience

One of the biggest reasons researchers flock to ionic liquids centers on stability. Many of the ones I’ve handled, like 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate, barely flinch under tough conditions like high heat or strong acids. These liquids laugh off most air exposure and resist breaking down in sunlight. Knock an open bottle off the lab bench, and you don’t lose half your volume or stink up the room.

That said, it still pays to dig deeper. Some ionic liquids—especially the ones built with organic structures—start to suffer when left out in open air for long stretches. Depending on the anion, moisture from air can sneak in and break down components over time. For example, most chloride-based options grab water quickly, which can trigger hydrolysis and shift their chemistry. Flammability won’t keep you up at night, but long-term air exposure makes a difference, especially for purity.

Storing Ionic Liquids: Lessons Learned

Storing these liquids isn’t always as simple as screwing the cap on and tossing the bottle back on the shelf. The stuff you buy comes sealed for a reason—exposure to moisture and CO2 from air, especially for imidazolium salts, can mess with integrity. Many times, a desiccator becomes a close friend, keeping humidity away and the contents reliable. In high humidity labs, ionic liquids can cloud up or shift color overnight if left out.

Opaque, airtight bottles replace clear glass to block UV damage and moisture. Someone new to the field might think a standard chemical cupboard does the trick, but for expensive samples, I make space in a cold storage cabinet, especially below room temperature, to hold off any decomposition. For ionic liquids with PF6- or BF4- ions, extra caution becomes key, as they can react in the presence of even small acidic vapors to release toxic gases. Negative experiences with this are hard to forget, and simple labeling or color-changing indicators help track if a batch has gone bad.

Making the Most of Stability

Many labs run into problems from cuts in funding and overworked staff, skipping proper storage or skipping tests on chemical stability. Simple fixes like regular water content checks by Karl Fischer titration, or picking up airtight storage containers, make a real difference. If a storage room feels humid or air conditioning is iffy, desiccators or silica gel packs get cheap insurance status.

Clear communication on storage practices helps teams avoid mixing up stable samples with degraded ones. I keep logs on batch age and storage conditions, and recommend others do the same. Whenever a batch gets exposed, running an NMR or even just checking physical appearance keeps the workflow honest. Many waste hazardous chemicals from lack of stable storage—and that means lost time, money, and lab safety.

Solutions and Takeaways

Ionic liquids bring big promise, but without respect for chemical stability and storage details, even the flashiest compound loses its edge. Lab training, airtight containers, and regular checks guard samples and results. Small steps add up to longer shelf life and more trustworthy science. Finding the right balance with storage makes sure ionic liquids live up to their reputation and deliver the reliable performance researchers came for.

Why Chemical Safety Hits Home

Jobs in the lab never look as glamorous as in movies. You spend hours reading safety data sheets and double-checking labels. Most chemists get a gut feeling about substances with a name as long as 1-Pentyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide. The length usually hints at complexity—and real risks. Many ionic liquids, especially those containing imidazolium, catch the eye because they break away from typical solvents. Research labs turned to these for better efficiency and lower volatility, but that doesn’t mean nontoxicity.

What the Science Tells Us

Peer-reviewed studies and chemical safety databases don’t mince words. The cation in this compound—1-pentyl-3-methylimidazolium—carries potential for toxicity, especially in aquatic settings. Environmental groups flagged several imidazolium-based ionic liquids after routine toxicity tests revealed clear risks for fish and other wildlife. The bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide part adds to the concern. Fluorinated chemicals stay in the environment for decades. Researchers often find these building up in water, soil, and sometimes even in food chains.

Direct human contact opens another can of worms. Exposure routes include breathing dust or mist, spillage on the skin, and accidental ingestion. Toxicology studies—like those published in journals such as Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry—place some imidazolium salts in “moderate to high” hazard categories for skin and cell toxicity. Repeated or high-dose exposure has produced skin irritation and organ stress in animal models. These effects don’t always translate one-for-one to humans, but they send a logical warning: treat with respect, minimize exposure, wear proper gloves and goggles, use a fume hood for any transfer.

Environmental Persistence and Bioaccumulation

It’s easy to see the temptation of ionic liquids: they make tough reactions smoother, and they don’t catch fire like ether. The catch? Compounds like this one, with several fluorine atoms, resist breaking down. Sewage treatment plants can’t fully remove molecules like bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide. Over time, low doses released into wastewater can build up and move through the environment. Water fleas and small crustaceans often serve as early warning systems; lab tests show stunted growth and lower survival rates when these organisms face repeated contact with certain imidazoliums.

Improving Lab Safety and Accountability

People working with this substance can’t afford to rely on outdated habits. The path forward includes swapping in less persistent chemicals when possible or carefully tracing where waste streams end up. Chemical hygiene educators carry the responsibility of teaching young scientists about long-term impacts—not just the dangers of mixing chemicals, but what happens after the lab work stops.

Tighter workplace guidelines, better personal protective equipment, and real-time air monitoring now play an everyday role in many labs. Some countries push for stricter inventory control, labeling, and disposal reporting. These steps aren’t red tape—they come from real incidents where spills or improper disposal led to contaminated groundwater or worker illness.

Looking Ahead

Every chemical choice tells a story. Picking 1-Pentyl-3-Methylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide means committing to extra responsibility. If a process calls for this compound, it pays to review fresh toxicity data, check disposal restrictions, and ask if a safer alternative exists. Organizations that stay ahead of the curve show real respect for both worker health and environmental standards—and often escape costly accidents. Experience in the lab proves that reading beyond the label keeps everyone safer.

A Closer Look at an Everyday Compound

You find sodium chloride in just about every kitchen. Common table salt doesn’t grab headlines, but its properties shape both our food and the industries behind the scenes. Looking past its role at dinnertime, you notice how much science sits behind each pinch.

Physical Traits You Notice

Salt arrives as a white crystalline solid. Each crystal forms a cube, which you can see if you look closely under a magnifying glass. Granules crunch beneath your spoon, telling you something about its hardness. On the Mohs scale, sodium chloride ranks at about 2 to 2.5, meaning fingernails can scratch it but it will outlast chalk. Melting requires heat—specifically, about 801 degrees Celsius. Boiling jumps to 1,413 degrees. That wide spread shows great temperature stability in solid and liquid states.

Sodium chloride dissolves well in water. The classic image—salt vanishing in a glass—reflects an important point: this compound is highly soluble, reaching up to 360 grams per liter at 25°C. In oil, on the other hand, it just settles at the bottom, refusing to mix.

Chemical Behavior That Matters

The formula NaCl looks simple, but behind those letters, sodium and chlorine create a strong ionic bond. Pour it in water, and the crystals break apart into Na+ and Cl− ions. This ionic nature supports the electrical conductivity found in saline solutions, which matters in everything from home water softeners to hospital IVs. Without those ions, sports drinks and medical treatments wouldn’t work the same way.

Sodium chloride doesn’t burn, nor does it give off dangerous fumes under normal conditions. At the same time, it resists most chemical reactions at room temperature. Acids like hydrochloric or sulfuric won’t faze it. Still, leak a little electricity through a saltwater solution, and you’ll split the compound, making chlorine gas and caustic sodium hydroxide. This process, called electrolysis, serves as the backbone for several big industries worldwide.

The Bigger Picture in Daily Life

Folks with high blood pressure hear about salt all the time. It pulls water into the bloodstream, raising volume and pressure. Doctors point to these properties when talking about diet. In my own family, switching to less salt made a real difference for someone with hypertension. This simple change cut down on headaches and kept blood pressure in check without heavy medication.

Industries use sodium chloride beyond the table. Treating icy roads, preserving foods, dyeing fabrics—each application leans on an aspect of salt’s physical or chemical qualities. Road crews use coarse grains because they cut through slush and melt ice by lowering freezing points. Food manufacturers cure meats since salt draws moisture out, holding bacteria at bay. My own hands have mixed brines for homemade pickles, relying on salt’s power to draw water from cucumbers and preserve flavor.

Reducing Problems Linked to Salt

Understanding how much salt ends up in rivers after a long winter, city planners face tough choices. High salt concentrations can harm aquatic life and leach heavy metals from pipes. To limit these effects, some towns swap out sodium chloride for alternatives like calcium magnesium acetate. Others use real-time weather data to time salt spreading more carefully, avoiding overuse during mild storms.

Sodium chloride may appear ordinary, yet its basic properties touch science, health, and the environment. Handling it with better planning and a deeper grasp of its chemistry helps solve problems that stretch far beyond what’s on the dinner table.

Digging Into Solvents and Electrolytes

Deciding if a product fits as a solvent or electrolyte in electrochemistry really pushes me to look at my own hands-on experience in the lab. Handling chemicals day in and day out, you notice that not every clear liquid or salt makes itself useful where ions move and reactions pop. Electrochemistry lives and dies by the details—solubility, reactivity, conductivity, safety. Before rolling out something new, I always ask: Can it carry current? Will it trigger side reactions? How does it hold up under voltage or at different temperatures? These aren’t just textbook questions. My own frustration grew the day a seemingly harmless solvent set off a runaway side reaction that left me with ruined data and a week’s mess to clean up.

Specifics That Matter: Polarity, Stability, Compatibility

Polarity sets the tone for any good solvent. Water works wonders for many systems, but plenty of electrochemical devices call for something less likely to rust metals or break down in sunlight. Organic solvents like acetonitrile or propylene carbonate come up because they don’t just dissolve salts, they hold up against the stresses life throws at batteries or sensors. These aren’t trade secrets—just earned facts. I’ve watched simple mistakes in solvent choice slow down ionic movement or even corrode sensitive electrodes, turning promising setups into costly headaches.

Matching electrolyte with solvent also brings up questions of compatibility. Not every salt actually dissolves well outside of water. When a new product crosses my bench, I look at its dielectric constant, viscosity, and chemical structure against what I’ve learned. Can it let ions run free, or do they stick together? Every failed attempt to push lithium salts into a stubborn solvent reminds me: structure and chemistry matter. If a product’s too viscous, it chokes off conductivity. If it’s too reactive, it starts chewing up electrode surfaces. These aren’t “what ifs”; red flags pop up fast in practice.

Safety, Cost, and Environmental Impact

Every bottle in the stockroom comes with its own warnings. Electrolytes and solvents get hot in more ways than one. One leak of dimethyl sulfoxide or nasty perchlorates can have the whole building emptying fast, and not every shop can afford that kind of risk. A safe product doesn’t just keep researchers from harm—the right choice means better results, less equipment damage, and less paperwork. My time supervising undergrads convinced me: give people safe options and you cut down accidents by half.

Cost rears its head, too. Industry moves quicker on cheap, widely available options. It isn’t just big companies that count pennies; academic labs feel pressure to stretch grants. If a product demands fancy purification or high-end waste treatment, interest starts to dry up, no matter how well it performs. I remember the short-lived excitement around ionic liquids. Their high price and tricky disposal meant only a handful of groups could really dig in.

Environmental impact can’t be ignored. A product that doesn’t break down or pollutes groundwater turns fast from promising to problematic. Growing up near rivers tainted by industrial run-off, I stay suspicious of new chemicals touted as green without real third-party data. Sustainable chemistry needs real transparency on what happens after the experiment ends.

Finding the Right Fit and Moving Forward

Evaluating a product for electrochemical work isn’t just a box-ticking exercise. Every success or failure in my lab comes from honest review, clear metrics, and wide-open curiosity. The top performers get there through stability, solubility, safety, affordability, and a clean environmental profile. Sometimes the leap to something better comes from re-examining old favorites; sometimes it's a brand-new compound with solid evidence behind it. Surprises come to those who put in the time, ask the hard questions, and respect the unforgiving nature of electrochemical systems.