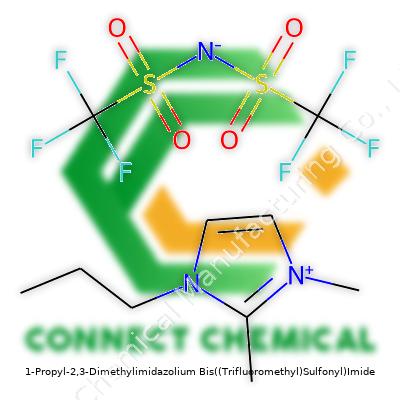

1-Propyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide: A Practical Perspective

Historical Development

Researchers looking for greener solutions began exploring ionic liquids in the late 20th century. Classical solvents for industrial use, like toluene and acetone, raised one red flag after another: volatility, toxicity, and complicated waste management protocols. 1-Propyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide (often shorted as [PDMIM][NTf2]) stands as a product of this period—where innovation answered the call for less hazardous, higher-performing alternatives. Years of looking for stable, non-volatile compounds led chemists to design and tune ionic liquids such as this one by stacking on methyl and propyl groups for stability and adjusting the anion for a wide liquid window. It sprang into view in published literature on advanced electrolytes and soon after showed up in patents for specialized solvent systems.

Product Overview

At first glance, [PDMIM][NTf2] looks like an oily liquid with no color but a reputation for getting things done in tricky environments. The imidazolium cation brings a certain chemical flexibility. The bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide anion offers impressive thermal and electrochemical stability, making [PDMIM][NTf2] suitable for projects where many solvents fail to deliver. This liquid doesn’t give off much vapor at room temperature, so you don’t get the usual solvent haze in labs or pilot plants. It handles temperature swings and electric stress without coming apart or charring.

Physical & Chemical Properties

[PDMIM][NTf2] typically turns up as a viscous, light yellow to colorless liquid above room temperature. Its melting point usually slips below freezing, sometimes dipping under -10°C, making it reliable even when chills roll through production spaces. The density sits close to 1.4 g/cm3 at 25°C, and high purity samples pour clear with little odor. Viscosity runs higher than common organic solvents, but this can be an advantage in applications needing stable mixtures. It dissolves more polar compounds than you’d expect—plus, it even tolerates a bit of water, which means less trouble drying glassware or worrying about trace humidity. Electrochemical windows tend to stretch, giving 3–5 volts depending on electrode material, so engineers use [PDMIM][NTf2] in high-voltage battery systems. Its hydrophobic nature resists water pickup, and it resists both acidic and basic attacks better than most chlorinated solvents.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Labs looking to buy or ship [PDMIM][NTf2] want to see clear details on purity, water content, and halide contamination. Most suppliers run quality checks using NMR, ion chromatography, and Karl Fischer titration—critical for scientific or engineering contexts where even parts-per-million impurities cause big problems. Labels ought to report the IUPAC name, batch number, production date, and prominent hazard symbols for corrosion or possible toxicity. UN numbers and GHS-compliant hazard statements show up on drums and bottles. For large volumes, drums often get inert-gas overlays to prevent moisture degredation, and transport follows guidelines developed for other non-flammable liquids. Storage recommendations push for cool, dry spots away from acids or oxidizing agents.

Preparation Method

Chemists build [PDMIM][NTf2] in steps, starting with alkylation of 2,3-dimethylimidazole using 1-bromopropane under controlled heating. Watch out for side reactions, so labs often add inert atmospheres and stick with dry solvents. The resulting [PDMIM]Br salt then gets swapped out through metathesis with lithium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imide in water or acetonitrile. After the reaction, the product gets washed to pull out lithium bromide and dried under vacuum until every bit of water is gone. Purification runs smoother when using phase separations instead of distillation, since the ionic liquid won’t evaporate well at common pressures. Analytical tools check for color, residual bromide, and organic byproducts to confirm product meets standards for use in sensitive areas like electronics or pharma.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

[PDMIM][NTf2] doesn’t just sit in a flask. Under the right push—heat, light, electricity—it can act as a solvent, electrolyte, or even a participant in some synthetic schemes. Other imidazolium variants tend to decompose under strong bases, but this one hangs on unless exposed to extremes. Halogens and strong oxidizers eventually prove too harsh, but regular organic syntheses carry on without breakdown. Some researchers fine-tune its properties by swapping out the imidazolium alkyls to tweak solubility or add function, but most stick to the standard form for performance in energy storage and catalysis. In lab practice, using [PDMIM][NTf2] as a medium often accelerates reactions that drag in low-polarity traditional solvents, opening up routes for new products and shorter reaction times.

Synonyms & Product Names

Suppliers and researchers trade several names for this compound. People call it 1-propyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide, [PDMIM][NTf2], or just “propyl-dimethylimidazolium NTf2.” Some catalogs stick with the systematic name; others drop the parenthesis and use TFSI for the anion. Misspelled labels or swapped digits pop up from time to time, so researchers always double-check the structure before kicking off an experiment.

Safety & Operational Standards

Legitimate safety protocols guide how people handle [PDMIM][NTf2]. Direct skin or eye contact causes irritation, so gloves and splash goggles show up in MSDS sheets and lab SOPs. Despite its non-volatility, the compound shouldn’t go near open flames or strong oxidizers, given theoretical risk of decomposition to toxic gases under fierce reaction conditions. Clean gear and secondary containment trays matter during transfer, since spilled ionic liquid stains surfaces and can stick for ages. Waste goes into special bins for incineration following local hazardous material laws. Regular ventilation and spill kits round out safe operation—any worker with real lab time under their belt knows a little caution prevents big, expensive messes.

Application Area

[PDMIM][NTf2] found its first real calling in electrochemistry, where stable, wide-voltage solvents matter for lithium-ion or next-gen batteries. Supercapacitors, which need media that won’t break down under high charge/discharge rates, also benefit from the liquid’s resilience. Researchers blend it into lubricants for gears that run hot or at high vacuum, where mineral oils come up short. Its non-flammable, hydrophobic character makes it a helper in harsh process environments—extracting rare metals from scrap electronics or refining pharmaceutical intermediates where trace water ruins the reaction. Environmental chemists use it to soak up pollutants or mediate recycling schemes; it absorbs hydrophobic organics that water misses. Oddly enough, some labs pour small amounts into polymerizations or doping setups to boost performance in flexible circuit materials, LEDs, and demanding sensors.

Research & Development

Academic and industry labs keep pushing the limits. Modifications on the imidazolium ring or anion tune physical behavior, hydrophobicity, or environmental toxicity. Groups look for easier preparation routes with fewer steps or safer, less expensive reagents. Custom ionic liquids based on this backbone offer task-specific solvents, but with the technical know-how to navigate synthesis and quality control. Ongoing work focuses on recycling: since these compounds don’t break down quickly, scientists want to recover and reuse them rather than burn or dump them. This push links directly to global goals for circular chemistry and reducing the chemical industry’s carbon footprint. Peer-reviewed literature constantly reports new data on stability, compatibility, and breakthrough uses in fast-growing tech.

Toxicity Research

Every new class of compounds raises questions about health and environmental risks. Toxicology studies on [PDMIM][NTf2] show low volatility, but moderate acute toxicity by ingestion or skin absorption in animal tests. Chronic, low-level exposure hasn’t been studied as much, so prudent labs keep exposure near zero. Water solubility remains very low, suggesting less environmental spillover—though disposal into wastewater doesn’t fit with responsible handling, since persistence in soil raises alarms about slow microbial breakdown. Some aquatic toxicity turns up in studies on imidazolium-based ionic liquids as a group, causing immobilization in Daphnia magna at higher doses, but real-world environmental contact stays limited if users follow disposal protocols. Industry and environmental agencies continue to track long-term impacts as new applications ramp up.

Future Prospects

[PDMIM][NTf2] doesn’t serve as a universal green solvent, but it holds a real stake in specialty applications where most commercial solvents can’t compete. Energy storage, specialty separations, and durable lubricants anchor present-day uses. Researchers are dialing in on biodegradable analogues and cost-cutting in synthesis to open up bulk markets. If regulators keep pushing for phaseouts of volatile organic compounds and hazardous solvents, demand for robust ionic liquids like this one will keep climbing. The bridge between bench-scale formulations and full industrial scale-up hinges on cost, safe handling, and proven routes for collecting and recycling the liquid after each use. Watching the speed of publication and patent claims, it’s clear this technology has plenty of runway left for practical, meaningful impact on green chemistry and next-generation energy systems.

Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquids on the Frontline of Green Chemistry

Ionic liquids have carved out a future for themselves in labs and industries, offering an alternative to volatile solvents. The compound 1-Propyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide, sometimes abbreviated as [pdmim][NTf2], truly matters in this evolution. What sets this material apart is its remarkable ability to dissolve a large variety of organic and inorganic substances, while showing almost no measurable vapor pressure. This quality alone wins the attention of chemists looking to cut down exposure to toxic vapors, waste, and the ever-present risk that comes from open beakers of noxious chemicals.

The Real-World Application: Electrolytes in Next-Generation Batteries

Digging into the daily use, the biggest story centers on batteries—especially the quest for safer, more reliable lithium-ion cells. Researchers have been searching for safer electrolytes that still deliver the performance needed for energy storage. Traditional organic solvents, like ethylene carbonate, often catch fire or break down in extreme conditions. In comparison, ionic liquids like [pdmim][NTf2] open the door for higher thermal stability. Testing in academic and industrial settings shows that batteries built with this salt manage to avoid combustion across a much wider temperature range. Experiments at national labs show lithium-ion conductivity doesn’t have to be sacrificed for safety. For electric cars, stationary storage, or even aviation, these qualities make a difference in reducing both risk and maintenance.

Catalysis and Synthesis: Streamlining Chemical Manufacturing

Outside the battery field, [pdmim][NTf2] finds practical use in catalysis and synthesis. Pharmaceutical companies and materials scientists use it as a unique reaction medium. In manufacturing fine chemicals, the ability of this ionic liquid to solubilize both catalysts and substrates means reactions proceed faster and with fewer side-products. For instance, Suzuki couplings and selective oxidations have shown higher yields with less environmental impact. Technical papers back up these claims, noting increased productivity and the advent of “recyclable” reaction media—no more dumping spent solvent down the drain.

Challenges That Still Require Solutions

There’s no magic bullet. The production cost of these ionic liquids remains higher compared to common solvents. Scarcity of large-scale suppliers pushes up the price. While the toxicity of [pdmim][NTf2] itself remains low, breakdown products and the fluorinated anion carry unknowns for long-term waste management. Researchers at green chemistry forums highlight this bottleneck. I’ve seen first-hand that regulatory frameworks haven’t caught up with the pace of research. Chemical engineers, regulators, and corporate safety leaders must work together, sharing test data and process tweaks, so these advanced materials don’t trade one problem for another.

Practical Steps Toward Safe, Scalable Adoption

Industry won’t shift en masse without convincing data, affordable pricing, and support from safety experts. Making this compound viable for widespread use comes down to three things: collaborative research on cost-cutting synthesis routes, open-access toxicity and biodegradability studies, and investment in recycling infrastructure. Government labs can fund pilot projects that prove recyclability, while universities and startups push for scalable syntheses. The ripple effect could transform battery manufacturing and chemical processing in a way that lines up with sustainable development goals, rather than short-term profit alone.

Peering Into a New Class of Materials

I remember standing in a small university lab, peering into a beaker with a classmate, both baffled by a clear liquid that wouldn’t freeze—no matter the temperature. We had our hands on an ionic liquid. Back then, I didn’t realize how much these liquids would matter for chemistry and technology.

What Makes an Ionic Liquid Different?

Ionic liquids act unlike the solvents most people know from school. A common solvent, like ethanol, evaporates and frequently brings along flammable fumes. Ionic liquids rarely do this because of their structure. They consist of positively and negatively charged ions packed together, but not so tightly that they lock up into a solid. At room temperature, these ions slide past each other and stay liquid.

Physical Properties That Matter

The physical properties of an ionic liquid can throw off expectations. Try pouring some, and the first thing you notice is the weight. The density sits much higher than water, making even a small vial feel significant in the hand. Viscosity depends on the particular ions—longer chains or bulkier structures in the cation or anion lead to thicker, almost syrupy textures. On lab days, I used to swirl the vial and watch the slow movement, like honey on a cold morning.

Ionic liquids usually avoid volatility. This means they stay put, not wafting their molecules into the air as easily as traditional liquids. Low vapor pressure translates to greatly reduced fire hazard in many labs, freeing up some headspace for focus. Ionic liquids handle wide temperature ranges without breaking down or thickening too much, which allows them to play a bigger role in high and low temperature reactions or devices.

Chemical Behavior in the Real World

From the chemistry side, ionic liquids offer up a massive solvent flexibility. Their dissolving power stretches across chemicals you’d never thought could mix. This comes down to the tunability of their ion pairs. Swap out one ion for another, and suddenly the liquid might prefer dissolving organic molecules, metals, or even complex bio-materials. This customization proved vital for researchers pulling rare earth elements from discarded electronics—something I tried myself during a short project on recycling phone components.

Another strong point: ionic liquids often resist breaking down under harsh conditions. Ultraviolet lights, electric fields, or strong acids chew through most organic solvents, but the bonds in ionic liquids frequently hold up. This makes them attractive for next-generation batteries, fuel cells, and even as catalysts for tough chemical reactions. Several studies (such as work from the Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters in 2023) back up their ability to perform under stress, a property that expands what industries can expect from chemical processes.

Addressing Environmental and Safety Concerns

The big hurdle comes from their lifecycle. Some ionic liquids, for all their remarkable stability, hang around in the environment for ages. Early versions included toxic ions that turned out to be harmful to aquatic life. The community responded to mounting evidence by shifting research toward ionic liquids based on natural or biodegradable ion structures. Today, green chemistry journals often highlight newer compounds that break down safely after use, such as choline-based versions used in extraction and processing. Transparent safety data and ongoing toxicity testing firmly ground these advances.

Pushing Toward Better Solutions

Ionic liquids challenge many old assumptions in both research and industry. They force chemists like myself to reconsider solutions for waste, energy, and safety. Factories using them cut down significantly on air pollution, since fumes stay out of the air. In energy storage, ionic liquids help batteries last longer and minimize risk of fire. These liquids prove that a shift in chemistry can nudge entire industries toward safer, cleaner practices—if each innovation keeps health, cost, and environmental futures in mind.

Recognizing Risks: Getting the Basics Right

Plenty of products on the market bring both benefits and risks. Stores sell cleaners packed with chemicals strong enough to cut through grime, but just as likely to harm skin or lungs. Kids’ toys sometimes show up with parts too small for safety. Electric tools speed up work but punish mistakes in seconds. If you’ve spent time around household products or job sites, you already know how easy it is to overlook those bright warning labels stamped on bottles or boxes. Ignoring them often leads to trouble—sometimes a trip to the ER, sometimes worse.

Knowing what’s in a product matters. Bleach, for example, causes burns on contact and throws off toxic fumes if mixed with ammonia. Lithium batteries, left loose in a toolbox or pockets, find ways to short and start fires. Disposable vapes bring nicotine plus flammable batteries into homes—double the hazard for families with kids or pets. At home or work, rushing through cleanup with a new product can blindside people with unexpected reactions. Eyes sting, throats close, or strange smells creep from cracks in the packaging. I’ve adapted my cleaning habits over the years: using gloves for harsh detergents, stashing the more dangerous stuff on high shelves, and never trusting packaging to keep curious hands out.

Smart Habits That Head Off Trouble

It doesn’t take fancy gear to lower risk, but it does take common sense and a bit of discipline. Reading the directions and any warnings can feel like a chore, but I’ve seen simple steps prevent a mess from turning into a disaster. Gloves keep acid and solvents away from skin, especially if you cover up exposed arms. Good ventilation clears away fumes that creep from strong cleaners, paints, or glue—you don’t want to breathe that in. Safety glasses may feel clumsy, but I’d rather look silly for a minute than spend hours flushing my eyes.

Labels usually lay it out plain. Some products demand storage far from food or heat sources. Others should never go near kids or pets. Sprays with propellants can explode if left in a hot car. Power tools need checked cords and sharp bits. Even non-toxic products can cause reactions, especially if you are sensitive to fragrances or preservatives. I always find it easier to keep original packaging, since tossing out instructions means you end up guessing about every step later on.

Companies bear some responsibility. Safer packaging and honest labeling go a long way. As a parent, I watch for child-resistant caps and check ingredient lists for allergy triggers. When safe alternatives exist, I reach for greener products or ones marked with clear safety standards.

Solutions Start With Awareness

We don’t live in a risk-free world. Tiny steps—gloves, goggles, open windows, distancing hazards from little hands—cut danger down in a way expensive safety tools never could on their own. Knowing the hazards, whether hiding in a household cleaner, battery, or unfamiliar gadget, gives everyone a fighting chance. Training families, workers, and friends to respect safety recommendations turns knowledge into habits, and those habits can save lives.

The more companies invest in honest labeling and user-friendly protection, the less often we see needless injuries or close calls. Watch out for shortcuts. Choose the right protection. Pass on the habits that keep people safe, instead of just taking risks for granted.

Understanding What’s at Stake

Dealing with chemicals like 1-Propyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bis((Trifluoromethyl)Sulfonyl)Imide, a mouthful for sure and typically called an ionic liquid, demands a grounded approach to safety. An ionic liquid might sound exotic, but in labs and industry, it pops up as a solvent, catalyst, or electrolyte because it can tolerate some serious heat and handle moisture better than the average chemical. Anyone working with it will notice a faint hint of chemical aroma and a thick, viscous feel—nothing you’d want on your skin or in your lungs.

Storage Conditions Matter

Let’s be honest—most accidents don’t start in the lab, but in the storeroom. I learned this the hard way as a young chemist, opening a bottle that had been stored near a radiant heater. Strong odors and pressurized caps were the giveaways that something had gone wrong. This isn’t just nitpicking: Ionic liquids like this one tend to break down in heat, and while they handle moisture better than sodium metal, they’re still happier in a cool, dry place. Most teams use refrigerators set between 2°C and 8°C, away from the lunch leftovers, with the chemical tightly sealed in glass or non-reactive plastic containers. Avoid metal unless you know for sure it won’t corrode; these salts have a mind of their own with metal ions.

Light also comes into play. Sunlight streaming into storerooms creates warm spots and degrades sensitive chemicals, so shelves away from windows (and lined with sturdy, labeled containers) keep surprises to a minimum. Reliable labels with the full chemical name and hazard info reduce mix-ups—I’ve seen too many folks reach for “the blue bottle” and realize at the last second they grabbed the wrong compound.

Handling: Respect Goes a Long Way

In labs, no shortage of folks have underestimated ionic liquids because they don’t splatter or evaporate fast like ether or acetone. Familiarity breeds complacency, but gloves—nitrile, not latex—are non-negotiable, and if you get splashed, washing up right away spares your skin. Make sure goggles fit snugly, because this salt stings and burns just like any strong solution. Ventilation matters too, especially if you transfer or mix the liquid, as fumes linger and can irritate your eyes and throat.

We store spill kits right by the ionic liquid storage, and it’s paid off before. Small leaks get cleaned with absorbent pads and a neutralizer, which usually means a mild base. No one uses shop rags or paper towels—these soak up liquid but spread contamination. Waste gets chucked in a dedicated bin for hazardous chemicals, and the area gets wiped with a detergent solution, not just water. I tell new hires there’s no glory in seeing how quickly you can clean a mess—slow and steady keeps everyone safer.

Building a Safety Culture

Nothing beats a well-placed warning sign or a training session that drives home what happens if you get careless. Teams that log every use, check expiration and hazard info, and report anything off-kilter keep accidents rare and minor. Safety goggles on the bench don’t keep anyone safe—they stay on your face. Sharing stories about close calls, without shame or blame, helps everyone learn and manage risk.

If you use this ionic liquid regularly, check the latest documentation, not just a worn-out printout from five years ago. Regulations change, new findings emerge, and the best practices shift. Respecting what the science says and trusting the experience of seasoned pros keeps work smooth, labs intact, and colleagues healthy.

A Close Look at Chemical Potential in Energy Storage

People love their phones, cars, and laptops, but few stop and think about the chemistry ticking under the hood. Battery breakthroughs don’t just appear overnight; research teams try dozens of new mixes before one finally sticks. The right chemical in a battery isn’t just about storing more power. Safety, raw material supply, cost, and how quickly ions move from one side to the other all shape how that battery works.

What Makes a Chemical Good for Batteries?

Ask someone who’s ever pried apart an old AA battery, power comes from how easily electrons and ions shuffle back and forth. Chemicals need to handle that game without falling apart too fast. For example, lithium itself shines because it’s light and gives up electrons quickly, letting devices go longer between charges.

But lab work reveals risks. Lithium reacts with water and air. Other chemicals, like nickel and cobalt, help pack a charge into a small space, but come with headaches. Cobalt mining in Congo raises alarms about worker safety. Price swings in nickel throw off production costs. The best chemicals usually balance energy, safety, price, and even where they come from.

Real-World Testing, Not Just Theoretical Promise

Books make almost any compound look promising with the right numbers. In reality, raw performance matters, but if the chemical corrodes metal parts, forms dangerous byproducts, or just costs a small fortune per kilo, companies walk away. I watched a startup try building zinc-air batteries. Early hype faded when electrodes quickly clogged up and the system struggled to work after a few recharges. This isn’t just bad luck—it’s in the chemistry.

Cathodes and anodes have to keep working in tandem. If a chemical breaks down after a hundred cycles, output drops, and the battery won’t last in a real device. Engineers try new combinations every year hoping to find something stable, powerful, and safe. Some look at organic molecules or sodium compounds because those elements are everywhere, not just in a handful of countries.

Possible Solutions and Where Innovation Heads Next

Fixing these challenges pulls in teams from across the globe. Finding safe coatings that keep new chemicals stable can open the door for non-lithium batteries. Sodium-ion, sulfur, and even iron-based batteries start making sense—especially for grid storage, where size and weight matter less than safety and price.

Clean processing and recycling rise in importance, too. I’ve seen labs test electrolytes that protect battery components from rotting away. Other groups explore lithium-iron-phosphate because it skips rare materials. Some hope artificial intelligence will sift through huge data sets and spot hidden gems among thousands of compounds. Real progress comes from thinking about the bigger picture: a chemical that works in the lab, can scale in factories, and won’t wreck ecosystems at the end of life.

For any chemical, researchers spend years figuring out its true potential for electrochemical work. There’s no magic shortcut, just trial, error, and honest conversations between labs and industry. The future won’t hang on one miracle chemical—it’ll need smart choices that line up science, sustainability, and practical needs for decades to come.