1-Propyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide: An In-Depth Commentary

Historical Development

Chemists first started exploring imidazolium-based salts seriously in the late 20th century as the push toward alternative reaction media grew. I recall reading about how organic chemists desperately wanted solvents that didn't catch fire easily and didn't poison the lab with fumes. As industries realized the drawbacks of volatile organic solvents, interest in ionic liquids shot up. 1-Propyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide evolved out of that period where researchers tinkered with countless side chains on imidazolium rings, seeking that right mix of melting point, viscosity, and solubility. The bromide counterion offered stability plus a certain simplicity in synthesis. The evolution of this compound runs closely with the newer wave of green chemistry that always asks: "Can't we do better for safety and the environment?" Now, it lands in a toolkit for both academic innovation and industrial process change.

Product Overview

Anyone who’s handled 1-Propyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide quickly learns it doesn’t behave like most laboratory salts. This material comes as a white to off-white crystalline solid, sometimes sticky, and likes to soak up moisture from the air. Known among chemists for reliably creating non-volatile, thermally stable, and conductive environments, it's tough and versatile. In synthesis, it swaps places with bulkier—and often smellier—reagents. What stands out is its low volatility and the near absence of toxic fumes. It fits snugly into what technicians call "designer solvents", letting users tune properties for tasks in catalysis or electrochemistry.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Running your fingers through the crystal powder, you'll note it clumps in humid rooms. The melting point sits around 110–120°C, giving a reliable baseline for process design. It dissolves in water and polar organic solvents, skips the need for aggressive heating, and holds up under microwave irradiation. The combination of a methyl group at the 2 and 3 positions with a propyl group at the nitrogen brings lower viscosity than bulkier alkyl chains—good news for folks who need fast mixing or want easy ionic mobility. Even at room temperature, solutions stay clear for extended periods, showing off chemical resilience not always present in standard salts.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Manufacturers label this compound with its systematic name, 1-propyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide, and the shorthand [PDmim]Br. Purity generally sits above 98%. Labeling always covers hazard notices, especially regarding its irritant nature to skin and eyes. Containers come tightly sealed with desiccant, bearing the CAS number, batch code, and storage recommendations to keep it away from direct light and moisture. Any reputable supplier will add spectroscopic or chromatographic certification, so users can check quality and confidently scale up synthesis without uninvited surprises.

Preparation Method

Anyone with standard training in organic synthesis can whip up 1-propyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide in the lab. I followed the standard approach in grad school—start by alkylating 2,3-dimethylimidazole with 1-bromopropane. The reaction runs in a polar solvent, often acetonitrile, at moderate heat. The trick is slow addition to avoid runaway heat and side reactions. Once the mix finishes bubbling, the product crystalizes on cooling or after adding ethyl acetate. Filtration, washing, and drying bring the salt to its final form. Sometimes, folks swap in anion exchange at this step for more exotic counterions, but the bromide sticks with classic protocols due to its efficiency and easy availability.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Under the right conditions, this imidazolium salt acts as both a stable solvent and a participant in organic reactions. Its ionic nature gives it exceptional ability to dissolve transition metal complexes for use as catalysts. In organic synthesis, the cation can promote nucleophilic substitutions and even help with the stabilization of unconventional intermediates. I've observed modifications where researchers swap the bromide for PF6− or BF4− when non-coordinating or hydrophobic properties suit the study. These anion exchanges unleash broader application, particularly for electrochemical cells or extraction techniques, adapting the parent structure in creative ways.

Synonyms & Product Names

This compound goes by a few names in catalogs and research papers. Common synonyms include PDmim-Br and 1-propyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide. Sometimes you’ll even spot abbreviations like [C3dmim]Br—especially in journals where page space runs tight. Commercial catalogs sometimes use internal product codes to keep things straight in warehouses. Whatever label it carries, the backbone stays the same: a three-carbon propyl, methyls at the 2 and 3 spot, and a bromide counterion.

Safety & Operational Standards

Every chemist needs to treat 1-propyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide with respect. Gloves, goggles, and fume hood work prevent skin and eye irritation—something I've learned firsthand after a careless spill. The material isn’t flammable, but it can cause eye redness or skin rashes. Spills mop up easily with water but never down the sink, as disposal must follow local chemical waste rules due to limited data on aquatic toxicity. Storage away from light and moisture keeps it from clumping or hydrolyzing, preserving shelf life. I always emphasize proper labeling—an unlabeled ionic liquid is a mystery you’d rather avoid in shared workspaces.

Application Area

In the last decade, 1-propyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide crept into a remarkable lineup of applications. Electrochemists value its high conductivity and stability in batteries and capacitors. Synthetic chemists enjoy its solvent power for tricky reactions—especially those sensitive to water or oxygen. I’ve seen it perform wonders in cellulose processing, pulling apart tough plant fibers more gently than acids or strong bases. In metal extraction and catalysis, its ionic environment can stabilize reactive intermediates or shuttle ions faster than sluggish, traditional solvents. Green chemistry circles keep a close watch on these imidazolium salts because they support less toxic, recyclable workflows, echoing demands for low-waste industrial procedures.

Research & Development

Laboratories continue dissecting every facet of imidazolium salts, constantly tweaking alkyl chains and counterions. 1-propyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide provides an interesting chassis—small enough for low viscosity, large enough to dissolve challenging organics and metals. Ongoing research covers its use as a solvent for biocatalysis, a medium for organometallic syntheses, and a stabilizer in next-generation solar cells. Some research circles focus on persistent challenges—mainly degradation under heat or in strong acid—prompting structural adjustments or the hunt for new purification steps. As industry demands compounds with tailored properties, the structure’s modular nature helps scientists anticipate problems like breakdown or leaching and to invent next steps in design.

Toxicity Research

Toxicology presents a critical question mark for broad adoption. Early findings suggest this salt isn’t acutely toxic to adult mammals at common lab exposure levels, though the ecological story unfolds less clearly. Some imidazolium salts hurt aquatic life, so ongoing research involves analytics to map degradation and bioaccumulation. Regulators and manufacturers pull toxicity data together to set limits for industrial emissions or accidental spills. Researchers crunch numbers and run exposure experiments with zebrafish embryos or daphnia to mimic real-world risk. Pulling from personal experience, cautious optimism about safety prevails in chemistry labs, driving teams to improve exposure controls and push for more public toxicity databases.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, chemists expect that 1-propyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide will keep earning a place in green chemistry toolkits. Synthetic routes will likely improve, pushing for lower waste and less energy-intensive processing. More nuanced toxicity assessments should help clarify environmental impacts; with that, regulatory frameworks and labeling standards could tighten to ensure safe handling not just in labs but also as applications grow industrially. Advanced battery and materials researchers eye modifications for ever-better performance, while solvent recyclers design ways to recover and reuse every drop. As society chases safer, greener technologies, this imidazolium salt stands to support not just risk reduction but also novel breakthroughs in energy, synthesis, and sustainable manufacturing.

More Than Just a Long Name

The name 1-Propyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide might look like alphabet soup to most folks, but behind the tongue-twister sits a compound that’s pretty handy around chemical labs. I’ve watched researchers grab for bottles of this salt whenever they need something with a bit of flexibility—something that can handle reactions without getting fussy. This stuff belongs to the family of ionic liquids, which basically means you get a salt that remains liquid at room temperature. No smoke or flash, just a clean solution that solves problems where others might struggle.

Helping Chemists Make Greener Choices

Most traditional solvents fill the lab with harsh smells and set off plenty of alarms about pollution and danger. I’ve been through uncomfortable afternoons due to the aroma of toluene or acetone hanging in the air. Because 1-Propyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide is an ionic liquid, it tends to be much less volatile. Fewer chemicals end up in the air, and folks in the lab get to breathe a little easier. That environmental bonus means researchers use this salt for dissolving all sorts of compounds, especially those that need a solvent but not the risky side effects. Universities and manufacturing plants have put these ionic liquids to work since the 1990s, chasing after cleaner and safer ways to make materials.

Speeding Up Industrial Reactions

Anyone who’s worked on chemical synthesis knows time matters—a lot. This particular compound often steps in to help speed up reactions or make them more selective. A good example comes in the world of catalysts; 1-Propyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide sometimes acts as both a solvent and a helper for catalysts to get the results companies want. Making specialty chemicals or pharmaceuticals demands precision, and the right environment can make the difference between a batch that passes quality control and one that ends up in the trash. Over the last decade, patents have piled up for using ionic liquids like this bromide-based salt in making everything from drugs to plastics.

Extracting Metals and Recycling Waste

One use that catches my eye is how this compound helps recover precious metals. Electronics waste piles up every year, and pulling useful materials back out for reuse has become a priority. Researchers have turned to ionic liquids because they can dissolve metals apart in ways water or other solvents just can’t. For example, silver and gold extraction from broken devices relies on solutions that grab the valuable stuff while leaving behind the junk. 1-Propyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide, with its unique chemistry, separates things cleanly—reducing contamination and sometimes even lowering costs.

Challenges and Smart Changes for the Future

Ionic liquids offer fresh options, but they aren’t perfect. Sourcing or disposing of them brings up concerns—it’s not always clear how these new-age salts behave once they leave the lab. Green chemistry keeps gaining support, so the next smart move means studying impacts from start to finish. Some research teams have begun testing how these compounds break down in the environment and what happens if they get into water supplies. Others have suggested tweaks to the molecular structure, using the same imidazolium backbone but swapping out side chains to limit toxicity. Companies devoted to chemistry should put transparency and sustainable development at the core of their business, so decisions line up with both health and safety and the climate goals we all share.

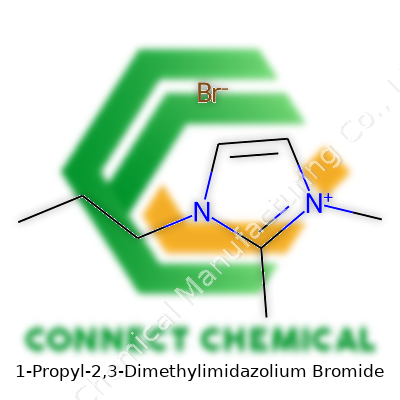

Breaking Down the Molecule

Digging into 1-propyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide, you see a chemical designed with both purpose and performance in mind. Picture an imidazole ring at the base, similar in look to a pentagon with two nitrogens holding the fort at positions 1 and 3. The “2,3-dimethyl” part hints at methyl groups stuck onto spots 2 and 3 of that ring, tuning the molecule’s physical properties and chemical quirks.

There’s a propyl group fastened to the nitrogen at position 1, a modest three-carbon tail that does more than just fill space. It plays a real role in shifting solubility, viscosity, and sometimes even how this salt behaves in a real-world lab setting. And on the other side, the bromide sits as the counterion, balancing out charge and enabling a whole menu of reactions. The chemical formula here lands at C8H15N2Br.

Why Structure Shapes Use

People often overlook the way a tiny shift in structure flips behavior on its head. Add a propyl instead of an ethyl, suddenly the compound dissolves differently or jets off into a new temperature range. In tasks like catalysis or solvent design, these tiny choices dictate success or a flopped experiment. The bulkier the groups on the imidazolium, the lower the melting point tends to run. Big reason so many see these compounds slot into the “ionic liquids” group—liquids that don’t dry up like water or ethanol.

Industry’s slow shuffle to greener methods makes these ionic liquids valuable. They don’t vaporize easily, so you don’t breathe in fumes, and they won’t catch fire so easily during use. The stability makes recycling and reuse more of a routine than a headache. Real lab experience tells me cleaning up after one of these ionic liquids means less worry about lingering fumes or hard-to-remove residues, since they stay put much more than old-school organic solvents.

Impact in the Lab and Beyond

In a lab, you want a solvent or catalyst that works every time, not just under perfect conditions. 1-Propyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide holds up during tough reactions, shrugging off heat and not breaking down before the job wraps up. In eco-friendly chemistry, that resilience stands out. The compound doesn’t break down into something toxic while it’s doing work. Chemists can plan multi-step syntheses knowing this ionic liquid won’t throw a surprise by-products party mid-reaction.

From my own work, ionic liquids have made some reactions not just easier, but possible in the first place. You get more control, less waste, and a cleaner separation at the end. There’s a learning curve, sure—more viscous liquids mean a slow pour and new stirring tricks, but after a few uses the routine falls into place. Colleagues in electrochemistry or extraction have said similar, finding these chemicals nifty tools for tricky separations or battery technology tests.

Challenges and Where to Go Next

Scaling up always throws new hurdles at the best ideas. Producing these specialized imidazolium salts needs pure starting materials and careful handling during synthesis, especially since unchecked impurities can wreck performance. Costs run higher compared to simpler salts or traditional solvents, so researchers angle for routes that cut waste and streamline purification.

Efforts in green chemistry point toward tweaking the alkyl chain or substituents on the ring. The aim is to keep performance high while trimming environmental impact further. Teams across the globe run small batch tests, swapping methyl for ethyl, or propyl for butyl, trying to land on better recyclability and lower toxicity. Each tweak means new challenges in purification and testing but also fresh opportunities for safer, better-performing materials.

Understanding Chemical Risks Through Experience

Talking about safety in the lab always brings up memories from my own work with ionic liquids and specialty chemicals. 1-Propyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide, with its mouthful of a name, falls into the class of imidazolium salts often used as solvents or electrolytes. The curiosity around safety isn’t out of place. Over the last decade, imidazolium-based ionic liquids have exploded in use across chemistry and engineering. Along with that surge, stories get shared—stories where something unexpected happened, and folks start asking whether these chemicals really are as harmless as some early papers made them sound.

This whole class received a reputation for “green chemistry” because of lower volatility compared to classic solvents. A liquid that doesn’t evaporate much seems great, right? But not all toxicity comes from fumes. I learned this the hard way working with similar imidazolium compounds—spilling a little on your glove and realizing how easily it seeps through unless you double-layer up. The structure of this specific salt, with its propyl and dimethyl groups tacked on, suggests it could hang around in the environment, especially since these salts tend not to break down quickly in water or soil.

What the Data Tells Us

Diving into published safety data, you won’t find large-scale studies on human exposure for 1-propyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide specifically. Most information comes from imidazolium salts as a group. Lab assays frequently show moderate toxicity toward aquatic organisms, especially algae and invertebrates. A study from 2013 out of Germany showed significant mortality in Daphnia at concentrations above 50 mg/L. Other reports flagged cytotoxic effects on human cell lines, especially immune and liver cells, often at low micromolar levels. This doesn’t mean everyone handling a bottle is doomed—just that the safety profile hasn’t been mapped out fully.

Some folks in chemistry still wave off these concerns, pointing out that quantities in research are small and that nobody’s chugging this stuff. It’s true, most exposure will come through skin or accidental splashes, not inhalation. But it pays to remember that many chemicals thought safe at the bench ended up showing more impact as they became popular. The experience with methyl mercury or certain pesticides comes to mind—nobody sounded the alarms until it was far too late.

Staying Smart in the Lab and Beyond

Keeping risks low means respecting what we don’t know. I always recommend double gloves, eye protection, and fume hoods even when working with “low volatility” compounds. Waste should go to a hazardous waste stream and not down the drain. Simple practice, really, but sometimes overlooked in busy labs.

On the regulatory side, more review and transparency help. Manufacturers and suppliers need to push for robust, independent testing on new specialty chemicals. The current REACH and TSCA frameworks demand some disclosure, though enforcement varies. Companies making or importing larger volumes bear more responsibility—if they want to market these compounds as “green,” full toxicology tests, chronic exposure studies, and environmental persistence checks should back up the claim.

For anyone using these compounds outside a tightly controlled workplace, the stakes rise. Water treatment companies, academic researchers, and manufacturers share responsibility for tracking where waste goes and monitoring for unexpected contamination. It doesn’t hurt to slow down and assume higher risk with any imidazolium-based compound until more is proven about long-term effects—for people and for the planet. The lesson from past chemical rollouts remains clear: better safe than sorry, every time.

Why Storage Can’t Be an Afterthought

Stepping into a chemistry stockroom, few people spare a thought for the real risks sitting on those shelves. From personal experience, it only takes one unexpected spill or degraded container for the dangers to show up. I’ve worked with ionic liquids enough to know that not every white powder or colorless fluid shares the same quirks. 1-Propyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide falls into this group. An imidazolium salt like this isn’t some everyday seasoning you toss in the pantry. This stuff demands real care, starting with where and how it’s tucked away.

Why Proper Storage Matters

A lot of labs cut corners, shoving bottles wherever they fit or leaving labels half peeled. Mistakes become real lessons when you realize moisture has crept in, changing the compound or, worse, creating toxic byproducts. The chemical’s shelf life can shrink fast, and purity may escape before you even get to your next experiment. Published data shows that even slight exposure to air can let moisture sneak into hydrophilic ionic liquids, altering their physical properties and reactivity. Dealing with spoiled chemicals means more wasted money and greater safety risks.

What Works: Environment Control

Keeping 1-Propyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide in an air-tight glass bottle, clearly labeled with hazard information, sets a strong base. I remember one lab mate who reused a water bottle as a chemical container; the result was a chalky mess and a round of safety retraining. Resealable glass with a reliable seal keeps outside air from creeping in.

Storing chemicals like this ionic liquid in a dry, cool place does the heavy lifting. A temperature between 15°C and 25°C helps slow down unwanted reactions. I learned early on that chemistry built on shortcuts won’t stick around. If your storage room creeps up over 30°C in the summer, that jump can make moisture absorption and degradation pick up speed. Moisture control, then, becomes more than just a good idea. Desiccators or specialized cabinets with silica gel make a difference if your lab air feels sticky.

Labeling and Inventory: Reducing Risks

A reliable system for tracking containers needs to be part of the setup. Handwritten notes fade, and memory tricks don’t always work. Logging each transfer, recording the date of purchase, and checking conditions each month can reveal problems before they spread. In one industrial lab I joined, the inventory sheet picked up a bottle with creeping black mold. It turned out moisture slipped in months earlier. Early action saved everyone the headache of decontaminating a much wider area.

Training and Mindset Matter

Good storage habits don’t last unless everyone buys in. Junior staff, students, and seasoned techs all end up sharing the same tight spaces and supplies. Training gives a clear picture of both hazard and handling. Most accidents I’ve seen grow from unfamiliarity and shortcuts, not malice. Real safety culture shows through in how people treat everyday routines.

Backing up these personal lessons, research in chemical safety consistently ties strong habits to fewer incidents and longer shelf lives for sensitive chemicals. Even so, rules work better with real follow-through—labels must stick, inventory checks must happen, and the urge to “just leave it there for now” has to be resisted.

Practical Fixes for Lasting Safety

If your lab struggles with shifting temperatures or humidity, investing in environment-controlled cabinets pays off. If forgotten bottles build up, regular inventory checks clear the clutter. Digital logs beat paper charts. Finally, sharing stories—mistakes included—keeps everyone alert. A team that knows why a bottle spoiled or a label failed stays ahead of trouble.

Care for 1-Propyl-2,3-Dimethylimidazolium Bromide and similar chemicals starts with where the containers stand and ends with the stories told in training sessions. Mistakes happen quietly; good habits are loud and obvious. Long-term safety and quality hang on the small details.

Getting to Know the Substance

1-Propyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide belongs to the expanding family of ionic liquids. These salts tend to stay liquid at room temperature and below, which stands out right away against traditional, more volatile solvents. Ionic liquids like this one usually combine an organic cation and an inorganic anion, and propyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide falls squarely in that category. In a lab, handling it means dealing with a white, sometimes off-white powder or a clear to pale liquid, depending on moisture and temperature.

Physical Profile in the Real World

This compound packs some interesting features. It’s highly hygroscopic, soaking up water from the air faster than most common salts. Leave a container open in a moderately humid room, and you’ll come back to a damp, sticky substance within an hour, sometimes even less. The melting point drops well below 100°C, often in the range of 70°C to 90°C, depending on purity and sample preparation. The material doesn't ignite easily and smells close to nothing, helpful when working indoors for long hours.

1-Propyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide dissolves well in water and mixes without a fuss with solvents like methanol and acetonitrile. Density lands a bit above water—most pure samples hover around 1.15-1.25 g/cm³. This comes from closely packed ions, which also give the substance a thick, almost syrupy feel if the material is kept slightly warm or moist. These traits can make cleaning glassware a challenge, so rinsing well with polar solvents becomes routine in any lab using it frequently.

Why Chemists Value These Features

Ionic liquids keep showing up in research because of properties like those in 1-propyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium bromide. Their negligible vapor pressure cuts down on air pollution in the lab and reduces fire risk—not many solvents give that peace of mind. When I handled them during my internship, the lack of strong fumes stood out compared to acetone or ether. That makes long synthesis days more bearable and lowers spill emergency risks in busy research groups.

Another benefit comes in the way they dissolve a dizzying range of substances. Some metal salts, organic dyes, and biologically active molecules struggle to dissolve in traditional solvents but slip right into an ionic liquid bath. This ability lets chemists try out green chemistry approaches, aiming to cut waste and scale up without so much hazardous junk. The nature of ionic liquids changes dramatically with small tweaks—putting a methyl group here, a propyl there. This flexibility lets scientists fine-tune melting temperature, viscosity, and solubility, focusing on exactly what they need for a reaction or materials process.

Where Trouble Starts

Not every lab is ready for what comes with ionic liquids. The same viscosity and sticky nature that helps dissolve tough compounds also makes spills harder to manage. My own experience cleaning up a beaker confirms it—paper towels tend to smear instead of absorb, and a bit of the material almost always stays behind unless you use a strong squirt of solvent. This residue sometimes interferes with sensitive electronics or glassware used for delicate reactions.

Many ionic liquids, including this one, raise some questions about long-term toxicity and environmental impact. While they don’t vaporize easily, that also means spills hang around, possibly leaching into waste streams. Current data shows low acute toxicity for the cation here, but more research tracks what persistent exposure does to people and ecosystems. Good lab practice means keeping tight controls on amounts used and waste disposal—something stressed by every safety officer I've ever worked for.

Finding Practical Solutions

Improving lab procedures starts with better training on handling sticky, viscous materials. Running small-scale tests with glassware helps newcomers get a feel for pouring and cleaning up. Researchers also need better waste management tools, including absorbent materials designed specifically for ionic liquids. Manufacturers can invest in designing compounds that degrade faster outside controlled environments or carry less toxic baggage in their breakdown products. Knowledge sharing—through open-access research or cross-industry talks—pushes everyone toward safer, smarter use of these promising chemical tools.