1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Chloride: A Closer Look at a Modern Ionic Liquid

Historical Development

Back in the late 1990s, the search for safer solvents started driving researchers away from volatile organics and toward ionic liquids. 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Chloride (often written as [PEIM]Cl) grew out of this period, crafted in university labs where scientists looked for salts that stayed liquid below 100°C. The imidazolium backbone marked a breakthrough, offering chemical stability and low melting points. Gains in ionic liquid chemistry followed, with [PEIM]Cl standing out thanks to its balance of manageable viscosity and thermal tolerance — something I noticed first-hand in labs aiming to decouple solvent properties from fire hazards. Funding flowed in from government science initiatives and green chemistry programs, helping research groups tweak the alkyl chains on imidazolium rings. This hands-on exploration showed the benefits of moving from methyl and butyl groups to ethyl and propyl substituents, delivering a product with fewer handling headaches and better results in tricky synthetic routes.

Product Overview

1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Chloride appears as a colorless to pale yellow, highly viscous liquid at room temperature. From a practical standpoint, it rarely picks up water from the air, making storage less of a hassle than older salts. Its growing catalog of synonyms – such as PEIM chloride, 1-ethyl-3-propylimidazolium chloride, or simply [C2C3im]Cl – signals increasing adoption across sectors. Chemical vendors pack it in amber glass as both research and technical grade. Reliability in performance makes this salt a staple for labs focused on electrochemistry, catalysis, and advanced separation science.

Physical & Chemical Properties

From my own tests and those in published data, [PEIM]Cl shows a melting point hovering near 40°C, a boiling point well above 250°C under inert conditions, and a density sitting near 1.1 g/cm³ at room temperature. Viscosity climbs as temperature drops, so heat and stirring help in practical handling. Unlike older chloride salts, it holds a wide electrochemical window and resists decomposition up to moderately high temperatures. The structure—an imidazolium ring with two branched side chains—yields solid ionic conductivity and chemical robustness. Solubility stretches to polar organic solvents, water, and certain glycols, with limited compatibility for non-polar hydrocarbons. In air, it shows good stability, though exposure to strong base or oxidizer leads to breakdown. These features feed into its allure for anyone trying to avoid the flammability or volatility found in most organic solvents.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Technical data sheets track minimum purity above 98%, residual water below 0.5%, and heavy metal content at trace levels. Product labels specify batch number, date of manufacture, and certifications for research or industrial use. From experience, suppliers who test each bottle for halide purity and include safety data sheets win repeat orders. Regulatory compliance—especially with REACH and local chemical safety guidelines—often finds a mention, as oversight bodies look closely at ionic liquids due to their novel status and diverse uses. Packaging makes a difference too: thicker glass, PTFE-lined caps, and clear hazard statements cut down on shipping mishaps, which I’ve seen slow critical research in shared university labs.

Preparation Method

Most synthetic routes for [PEIM]Cl begin with 1-methylimidazole as the core building block. One common approach reacts this ring with ethyl chloride to form 1-ethylimidazole, followed by alkylation with propyl chloride. Control of the reaction environment, especially temperature and stirring rate, earns trust from analytical chemists betting on lot-to-lot consistency. Scaling up leaves little room for error — small traces of di-alkylated or incomplete products show in NMR or mass spectrometry, affecting purity and end-use suitability. Careful washing with ethyl acetate or ether helps remove organic byproducts, while vacuum drying targets residual water and volatiles. In labs, maintaining a dry, inert atmosphere in the reaction flask pays off in higher yield and colorless final product.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

[PEIM]Cl lends itself to metathesis, or ion-exchange, reactions for generating a slew of functional ionic liquids. Swapping out the chloride with a more weakly coordinating anion, like PF₆⁻ or BF₄⁻, tailors material for non-aqueous electrochemistry. Imidazolium chloride’s cation also acts as an efficient phase-transfer agent in nucleophilic substitutions, Suzuki couplings, and select oxidation reactions. My own group has used it as a solvent and ionic matrix during enzyme-catalyzed synthesis, capitalizing on its ability to stabilize protein structures without denaturing them. Heating or treating [PEIM]Cl with certain amines or thiols can yield N-heterocyclic carbenes, pushing research into organometallic complexes and homogeneous catalysis. Each modification steps up process safety or expands the pool of applications.

Synonyms & Product Names

Vendors and journals stick with several accepted names for this salt. 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Chloride comes up most often, though [PEIM]Cl, [C2C3im]Cl, and 1-ethyl-3-propylimidazolium chloride also appear. Tradenames drift based on the supplier or targeted field; as more companies enter the ionic liquid market, new labeling conventions pop up, but I stick with IUPAC standards to avoid confusion in group collaborations and regulatory filings.

Safety & Operational Standards

With a relatively low vapor pressure and limited flammability, [PEIM]Cl poses less risk than standard organics, but gloves and goggles stay non-negotiable in handling. Direct skin contact can cause mild irritation, and accidental ingestion leads to discomfort; I’ve seen poor ventilation stir up lingering odor in closed labs after spills. Waste disposal falls under hazardous organics due to potential aquatic toxicity, so neutralization and collection in suitable containers is best practice. Safety data sheets flag the compound for environmental monitoring, urging efforts to keep effluent streams clean. Regular training on chemical hygiene and first aid, plus consistent review of new toxicology reports, helps teams avoid careless exposure in fast-paced research settings.

Application Area

Interest in [PEIM]Cl stretches across electrochemistry, catalysis, and green chemical processing. Battery researchers use it thanks to its broad electrochemical window and high ionic conductivity. Analytical chemists embrace it as a solvent for extraction of heavy metals and organics from complex environmental samples. In synthesis, it dissolves polar and even some poorly soluble reagents, steadying enantioselective catalysis or pharmaceutical manufacturing. Its use as a stabilizing medium for nanoparticles and enzymes brings breakthroughs in protein crystallization and biosensor development. I’ve seen it streamline nucleic acid extractions and reduce cleanup issues in chromatography. Its low volatility and thermal stability appeal to chemical engineers designing processes with minimal environmental emissions. By side-stepping the toxicity or air quality pitfalls of older solvents, [PEIM]Cl clears a path for safer, more efficient lab work.

Research & Development

Research into [PEIM]Cl often covers new synthesis strategies, improved purification, and expansion into emerging technologies like dye-sensitized solar cells or advanced capacitors. Grant-backed teams chase higher ionic conductivities, lower viscosity, and greener manufacturing pathways. Academic consortia pool data on structure–property relationships, supporting smarter choices for cation and anion pairs. The push for upscaling highlights needs for continuous-flow synthesis and modular purification — lessons I’ve picked up working with pilot plant engineers seeking more reliable routes from gram- to multi-kilogram batches. Open-access publishing and industry-academic partnerships speed up innovation, hack away at cost, and shorten lead times.

Toxicity Research

Toxicity profiles paint a mixed picture. Acute exposure usually causes mild irritation, but stories of imidazolium ionic liquids persisting in waterways and impacting local biology led to in-depth aquatic testing. Most studies peg [PEIM]Cl as moderately toxic to water fleas and fish at higher concentrations; continuous monitoring keeps levels well under regulatory thresholds. My time in industrial toxicology flagged the danger of relying only on short-term mouse or rat studies — we need more work tracing low-level, long-term exposure in real-world conditions. Calls for closed-loop use grow stronger, and interest mounts in designing biodegradable analogs to close the gap between performance and safety.

Future Prospects

The outlook for 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Chloride looks strong as industries shift focus to greener, safer solvent systems. Advances in computational chemistry and material science could widen its application in fields like carbon capture, next-generation batteries, and enzymatic synthesis. Sustainable manufacturing, life-cycle management, and regulatory compliance will steer future development; product stewardship moves from afterthought to headline concern. From my work in collaborative research consortia, it’s clear that real progress demands both high-performance materials and smart management of health and safety risks. Keeping these salts on the right side of environmental policy and public trust anchors their role in tomorrow’s laboratory and industrial toolbox.

The Changing Face of Laboratory Tools

In the last decade, anyone spending time in a chemistry lab would notice the rise of substances called ionic liquids. One such compound, 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Chloride, keeps showing up in research journals and conference posters. At first glance, the name sounds intimidating, but its uses tell an interesting story about where chemistry stands today.

Why Chemists Reach for It

Old-school solvents like benzene and toluene shaped the chemical industry but came with health and environmental risks. Once scientists understood the costs, the search for safer alternatives took off. Ionic liquids like 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Chloride made an entrance as non-volatile, thermally stable replacements. They won chemists over, partly because no head-throbbing fumes escape them, and they don’t burst into flames as easily.

I worked as a student in a materials science lab where we needed to dissolve stubborn polymers. Many organic solvents just couldn’t cut it, or they would evaporate halfway through the experiment. Trying out 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Chloride, we found materials dissolved rapidly and stayed dissolved—helping us avoid hours of repeat work. For labs, saving time and cutting down on chemical waste means a lot.

Opening Doors in Research and Industry

Ionic liquids take up a growing share of tasks. This particular compound finds regular use in cellulose processing—think of turning wood pulp into raw materials for biofuels. Experts like the late Professor Robin Rogers at the University of Alabama inspired years of study into how these liquids break down plant fibers. That research keeps fueling talks about greener paper mills and renewable energy sources.

In battery research, ionic liquids step in as safer electrolytes. Engineers want to keep pushing batteries to higher capacities. Using ionic liquids as electrolytes can bring more reliability and less risk of fires. This trait catches the attention of companies who see lithium-ion batteries as the future of transportation and storage. Tests with 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Chloride and its cousins point to batteries that work even at wide temperature swings.

Challenges to Widespread Adoption

Every time my team considered a new solvent, a big question stuck out: What will it cost? Ionic liquids like this one often hit the budget harder than standard options. For now, that puts them out of reach for many small companies. Synthesis routes—meaning, how companies make these chemicals—don’t always scale up smoothly. Factories struggle to streamline the process without leftover impurities. As a result, some applications wait on cheaper, cleaner production lines.

Toxicity doesn’t vanish, either. Not every ionic liquid is a model citizen for the environment. Researchers have learned to test carefully and avoid tossing these substances down the drain. If labs and factories treat them with respect, the impact stays smaller than many solvents from the past, but rules fail if future generations don’t learn how to handle them safely.

What the Future Could Bring

There’s hope on the horizon for those looking to make chemistry safer and more sustainable. Developing next-generation ionic liquids with friendlier price tags and better green credentials remains a hot area. Universities, national labs, and private research teams collaborate to bring costs down and lift performance higher. As material science, battery technology, and biomass processing keep evolving, 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Chloride could play a bigger role if its current hurdles get cleared. Until then, it stands as an example of what smart chemistry can offer and reminds us not to skip the safety and cost questions along the way.

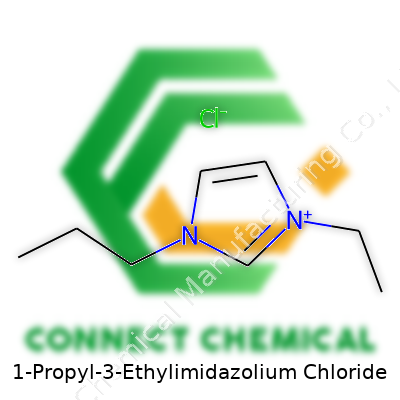

The Shape of the Molecule

Chemists usually picture a chemical structure as a map of atoms and bonds. For 1-propyl-3-ethylimidazolium chloride, this map begins with its imidazolium core. Picture a five-membered ring made up of three carbon atoms and two nitrogen atoms. At one nitrogen, a propyl group—that’s three carbon atoms in a row—hangs off the ring. Opposite that, the other nitrogen holds an ethyl group with two carbons. Chloride, the classic salt-forming ion, balances everything, but doesn’t jump onto the ring itself. If you sketch it, you see that most of the molecule’s bulk comes from these side chains.

The Role in Everyday Science

Ionic liquids like this one stepped into the lab limelight because they hardly evaporate and dissolve many things that regular solvents can’t touch. In high school, I used to mix salt with water and watch it swirl away. Here, that mixing happens on a more exotic scale. Liquid at room temperature, 1-propyl-3-ethylimidazolium chloride opens doors for chemists wanting less flammable, flexible solvents. It’s not about just finding a new way to mix chemicals for sport—the safety angle matters. Fewer fumes mean less risk to lungs; less flammability lowers hazmat worries.

Stability and Use

The specific mix of propyl and ethyl side chains on this imidazolium ring isn’t just artistic flair. Subtle shifts in those side groups tweak the molecule’s melting point, how well it works with water, and what kinds of things it can dissolve. Several labs use this compound to pull rare metals out of waste or recycle plastics. Journal articles show that swapping even a single carbon changes how two molecules interact. So, the shape isn’t just trivia—it’s the key to what this fluid can do.

The Challenges and Hurdles

Using ionic liquids sounds perfect until you get into the details. Many cost more than older solvents. Some break down if you heat them in the wrong way or let too much water in. Throwing away used liquids gets complicated too, since some of their broken-down products harm fish or soil microbes. This trade-off between safety in the lab and safety in the world pops up a lot. As a grad student, I learned firsthand how cleaning up after an experiment sometimes proved trickier than getting the reaction to work.

Looking for Better Options

Labs can test these molecules by tweaking the side groups or swapping chloride for other ions, aiming for greener formulas. Some research looks at ways to recycle and reuse these liquids after each round of reactions. It helps to test for toxicity early, even if most never leave the lab bench. Publishing negative results—what didn’t work—gets more attention now, so the wider community can skip dead ends.

Why Structure Still Matters

Every small change in the chemical structure of 1-propyl-3-ethylimidazolium chloride tells researchers something about future green solvents. Students, scientists, and engineers all get a little closer to safer, more efficient chemistry by sweating the details. Understanding structure cuts waste, saves money, and can protect both workers and the environment. That might sound simple, but it keeps chemistry moving forward, one molecule at a time.

Looking Beyond the Chemical Jargon

If someone asked me about 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Chloride during my first year working in a university chemistry lab, I would have had to dig for information. This isn’t a household chemical name like bleach or ammonia. But it pops up now and then, especially among people who deal with advanced materials and new solvents designed for industrial use. For everyday folks, the question isn’t about its performance — it’s about whether this substance poses a risk to people or the environment.

Drawing the Line: Hazardous or Not?

To figure out risk, a lot depends on the details. For many ionic liquids like 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Chloride, the conversation often comes back to toxicity in humans and aquatic life. Researchers, including regulatory agencies, judge toxicity by what happens after spills, contact with skin, and inhalation. Unlike traditional solvents—think acetone or toluene—a lot of these newer ionic liquids don’t vaporize much and tend not to ignite easily. This suggests less flammability and fewer harmful fumes at room temperature, which is a plus.

Toxicologists have flagged some imidazolium compounds for their effects on organisms in water. Some forms harm fish and small aquatic creatures at pretty low concentrations. That doesn’t mean every single ionic liquid poses a huge risk, but it does highlight the need for test data and common sense. Many chemical producers urge folks to avoid skin contact, use gloves and safety glasses, and keep ionic liquids away from drains. This is not paranoia—just basic precaution, which I’ve learned the hard way makes daily lab work much smoother.

Regulations and Fact-Checking

Diving into regulations, I look at safety data sheets and public data from the European Chemicals Agency and the US EPA. There’s no wide-scale ban on this compound because its use rarely leaves the controlled environment of labs or specialty factories. But that doesn’t mean it gets a free pass. Most chemical manufacturers categorize it as “irritant” to eyes, skin, and the respiratory system. Side effects show up mostly after direct or prolonged exposure. Chronic long-term risks—such as carcinogenic effects—haven’t been proven, but testing is ongoing. That’s a common story in this family of chemicals, where researchers work to balance technical properties with potential health effects.

A big lesson from past chemical mistakes involves what happens after disposal. Some ionic liquids build up in nature if they’re flushed away. No one wants to repeat the mistakes of the early pesticide era, so workers get trained to use closed systems and proper containers. Simple things, really—collecting waste for incineration and labeling everything—cut down on accidents and pollution. These habits don’t just protect factory workers, but limit leaks into air and waterways.

The Common-Sense Path Forward

So, what do we do moving forward? People who handle chemicals like this have to take personal and collective responsibility. Anyone working in science knows labs change as new data comes out. Better labeling, smart storage, personal protective gear, and ongoing toxicity testing keep the risk low. Industry leaders need to keep asking for alternatives that offer the same technical benefits with less environmental burden. At the same time, regulators have to watch for new evidence and step up rules if new findings demand action.

Years of hands-on lab work and helping train students taught me one thing: If you ever need to ask about toxicity, stop and read the data sheet, ask for the latest tests, and respect the unknowns. No one gets hurt by being careful.

Knowing the Principles of Chemical Storage

Nobody wants a chemical spill or ruined batch tucked away in a forgotten corner of the lab. I’ve seen situations turn chaotic from a simple oversight—containers sweating chemicals onto shelves, sticky residue under the lid, or the label fading beyond recognition. Storing chemicals like 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Chloride takes more than putting a lid back after you scoop some out. This compound is a type of ionic liquid, finding its way into battery research, green chemistry, and specialty synthesis. Because of its special structure, it demands honest attention to detail in storage.

The Real Dangers Behind Poor Storage

People sometimes shrug off risks in the name of routine, but chemicals like this don’t pardon sloppy habits. Storing 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Chloride in a humid room can ruin its purity. This substance loves water from the air, so any exposure adds impurities and messes with experimental results. One failed synthesis wastes time, budget, and can skew a whole project. Lab workers who open a jar, scoop out a bit, leave it sitting, and forget to reseal quickly learn how fast things turn south. From my own time in chemical stockrooms, the mess becomes clear after a week—a chunked solid, sometimes a pool of goo, impossible to weigh out the right amount, with a growing price tag on replacements.

What Works for Storing 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Chloride?

Experience and guidelines point toward the same simple plan. Choose containers with tight-fitting lids, preferably something corrosion-resistant like glass or high-density plastic. Clearly mark the label with the name, received date, and hazard information. Pick a dry, cool spot, away from sunlight or heat sources. A standard chemical cabinet with desiccant packs inside protects from moisture in the air. More advanced setups include desiccators with humidity indicators, which serve as a real-time check.

For longer-term storage, small aliquots reduce the number of times the bulk supply opens. If someone needs more, they grab an aliquot rather than repeatedly opening and closing a big jar. It also reduces the chance of contamination. Never underestimate the detail of wiping a lip before closing the lid; I’ve seen cross-contamination from dried chemical dust ruin more than one experiment. In shared spaces, communication helps too—a simple log or sticker system tracks who opened which sample last, and why.

Personal Responsibility in Chemical Management

Keeping labs safe and budgets under control means following these basic routines. Secure your stock, keep moisture out, label every jar, and don’t wing it with storage. I always keep a logbook on the shelf, within reach. If the material gets old or starts clumping, replace it. No experiment justifies taking shortcuts with safety or purity. Tools like humidity indicators, good quality containers, and careful habits go further than expensive storage gadgets.

Practical Steps for Every Lab or Facility

The storage of chemicals like 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Chloride does not come down to accident or luck. If your facility values research, safety, and return on investment, set a culture of careful handling from the start. Review guidelines, inspect stock regularly, and keep lines of communication open among users. With each step, the risks shrink—making for solid research, predictable outcomes, and a safer environment for everyone working nearby.

Looking at the Physical Side

A lot of folks in labs pick up 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Chloride, often written as [PEIm][Cl], because it behaves differently from water and most common salts. This compound puts itself among ionic liquids—a family of materials that look like liquids around room temperature but don’t rely on water. Pour it out, and you’re usually staring at a colorless to pale yellow fluid. People often notice that it feels a bit viscous, thicker than water, which comes in handy for controlled mixing.

Unlike standard table salt, this chloride doesn’t make crunchy crystals at the bottom of your jar. Instead, it usually sticks around as a slick, sticky liquid that doesn’t let go of moisture easily. That’s part of why so many researchers keep it sealed up—the stuff loves to soak up water from air, almost like a sponge. This property, called hygroscopicity, plays a starring role in how it handles and stores.

It also doesn’t like to catch fire. Compared to typical organic solvents that evaporate and go up in flames, [PEIm][Cl] holds its shape as a liquid up well above 100°C, and you’d struggle to light it with a typical flame. Its stability across a wide temperature range has opened the door to creative uses, especially for chemists pushing past normal limits.

The Chemical Personality

Digging into chemical details, this compound combines an imidazolium cation with a chloride anion. The imidazolium part shows strong ionic behavior—it holds on tight to the chloride, which explains why it doesn’t evaporate easily. Most organic solvents break up or boil long before [PEIm][Cl] budges.

Its resistance to breaking down in the face of acids or bases sets it apart. Pour hydrochloric acid or sodium hydroxide onto this ionic liquid and you may be surprised to find not much happens, at least not compared to most household chemicals. This chemical stability helps it survive both punishing lab conditions and industrial settings.

What really makes it special is how it interacts with other materials. 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Chloride can dissolve a wide list of substances that usually stay stubbornly solid or separate from regular water. Lignin from plants, cellulose from wood, and even some tough polymers start to break down in its presence. Many labs are using this ability to develop greener, cleaner ways to process biomass or recycle plastics, cutting down on hazardous waste they used to create with harsher chemicals.

Why Bother with This Compound?

Folks in the field know that finding a solvent that breaks barriers—stays stable under heat, doesn’t catch fire easily, and can dissolve difficult materials—can be a game changer. My own experience working with ionic liquids taught me how tricky temperature control is with regular solvents. Once I tried a handful of imidazolium-based liquids, the time spent dealing with hazardous vapors and constant evaporation dropped, and my team felt more relaxed in the lab.

The fact that [PEIm][Cl] skips some of the biggest environmental and safety headaches that hit traditional solvents means scientists can rethink old methods. They’re starting to run reactions with less pollution and more recycling. There’s nothing perfect out there yet, though. The current price for high-purity samples still runs higher than old-school options, and cleaning them up after use takes some planning. Still, with work, researchers can design waste treatment and recovery steps that fit better with this compound than with solvents that just disappear into thin air.

Steps to Move Forward

To unlock the full benefits, companies and universities will need to share best practices—especially when it comes to safely handling, recycling, and disposing of these liquids. Developing reusable purification setups and using renewable sources for the raw materials could cut costs and limit environmental impact. Grant funding that streamlines these efforts could bring the price point down and help smaller labs step into greener practices.