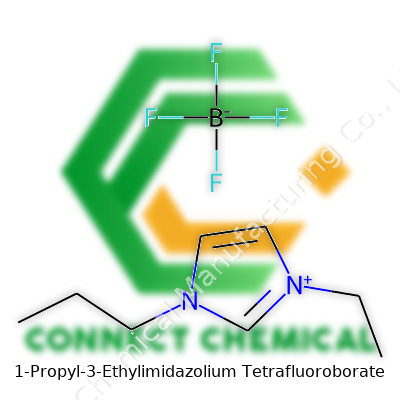

1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate: A Practical Look

Historical Development

Chemists often search for ways to replace volatile and hazardous organic solvents. Ionic liquids have stood out, and 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate (commonly shortened as [PEIm][BF4]) represents one of the newer alternatives that appeared at the turn of the 21st century. Before these compounds became popular in the laboratory, most chemical synthesis relied on solvents like ether, chloroform, and acetonitrile—each bringing its own safety baggage. Electrochemistry and catalysis, in particular, pushed research toward new solvent types. In those years, imidazolium-based ionic liquids, with their flexibility of design and stability, started gaining traction in journals and conferences. A decade after their introduction, commercial labs worldwide poured resources into evaluating and scaling processes with [PEIm][BF4] and its cousins.

Product Overview

[PEIm][BF4] brings together a straightforward structure—an imidazolium ring with propyl and ethyl side chains, and a tetrafluoroborate anion. It typically arrives as a clear, colorless-to-pale-yellow liquid, free-flowing and low-odor. Its low vapor pressure turns safety into a daily advantage. Compared to older salt-based solvents, its handling feels much safer, especially in environments that run multi-step syntheses and flow chemistry rigs all year. Commercially, it’s packaged in glass or Teflon bottles, with sizes ranging from laboratory milliliter samples to industrial-scale liters. Labels on legitimate batches always provide the precise molecular weight (about 226.1 g/mol), purity (98% or above), and the supplier’s quality control data—a growing expectation among chemists tracking batch-to-batch consistency.

Physical & Chemical Properties

This ionic liquid remains stable across typical lab temperature swings. The boiling point sits above 200°C under standard pressure but decomposition usually starts before reaching that mark, releasing toxic boron and fluorine species. Its melting point hovers just below room temperature, turning it into a liquid at standard bench conditions. Water solubility distinguishes it from many hydrophobic counterparts; this one mixes easily with water, acetonitrile, and polar solvents—yet separates from hydrocarbons. Its viscosity falls between syrup and light oil, which means stirring and pipetting require a careful touch. From experience, storage in dry, airtight containers matters, because prolonged exposure to air allows it to absorb moisture—sometimes altering reaction performance.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Reliable bottles of [PEIm][BF4] include data on water content (typically below 0.1%), absence of halide impurities, and a certificate of analysis. Safety sheets always remind users about its immiscibility with strong oxidizers and compatibility limits with base- or acid-sensitive reagents. Suppliers who focus on laboratory-scale lots usually indicate recommended shelf lives (1–2 years under nitrogen or argon) and storage temperatures (around 20°C for best results). Lot numbers and traceability codes show up on both carton and bottle, supporting research labs with good documentation practices or audits. Labels often display common synonyms too—like 1-Ethyl-3-propylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate and PEIM BF4—so chemists avoid mix-ups with dimethyl or methyl analogues.

Preparation Method

Synthesizing [PEIm][BF4] follows a direct path. Most routes begin with 1-ethylimidazole and 1-bromopropane, heated together under reflux in a polar solvent until a viscous imidazolium bromide forms. This intermediate then goes through metathesis with sodium tetrafluoroborate in deionized water. The target ionic liquid, less dense than the brine phase, separates cleanly after several washes. Purification, usually a matter of extraction and vacuum drying, removes residual halides and lowers water content. Large-scale plants adapt this approach with continuous reactors and membrane-based ion separation, scaling yields without carrying over the by-products that can haunt reactions downstream.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

In daily lab use, [PEIm][BF4] acts both as a reaction medium and a participant in ion-exchange processes. Its ionic nature stabilizes carbocations and radical cations, making it useful for Friedel–Crafts and transition-metal catalyzed couplings. Mixing with varying anions—swapping out tetrafluoroborate for hexafluorophosphate or bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide—lets chemists tailor melting points and solubility for target reactions. Some teams, myself included, found it helpful in biphasic separations: organic products slip quickly from the ionic phase after completion, reducing the pain of extraction. At higher temperatures or under strong nucleophiles, the imidazolium ring survives with little breakdown—but persistent bases or heat can drive ring-opening or decomposition, creating waste and toxicity hazards in recycling cycles.

Synonyms & Product Names

Chemists often see [PEIm][BF4] under various names: 1-Ethyl-3-Propylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate, PEIM-BF4, or simply by its CAS number 133213-96-0. Some catalogs lump it under "ionic liquids—imidazolium salts", together with close relatives like [EMIm][BF4] (ethyl-methyl) or [BMIm][BF4] (butyl-methyl). Experienced researchers double-check product codes and supplier aliases, since confusion over ethyl and methyl substitutions can upend experiments. Product sheets frequently bundle this salt with application notes, mostly to help chemists pick the right combination for catalysis, battery, or extraction work.

Safety & Operational Standards

Ionic liquids like [PEIm][BF4] have an impressive safety profile compared to older solvents. Still, its tetrafluoroborate anion can hydrolyze with acids or hot water, liberating fluoride or boron-containing toxins. Fume hoods stay essential. Gloves—nitrile or neoprene—prevent long-term skin exposure, which can lead to irritation or, in rare cases, dermatitis with repeated contact. Waste handling follows local hazardous waste rules; never mix with chromates or azides since those risk triggering unwanted reactions. Many labs, mine included, now store ionic liquids in amber glass with PTFE seals, keeping light and moisture at bay. Regular monitoring of container seals and periodic checks on stored solutions help avoid accidents, especially in teaching spaces or shared labs.

Application Area

Battery researchers turn to [PEIm][BF4] for its wide electrochemical window and non-flammable character—qualities that lithium-ion battery designers need to minimize fire hazards. Catalysis groups use it to recycle homogeneous transition-metal catalysts, saving both money and rare element supply. Extractive chemists pull metals like platinum, ruthenium, and rhodium from ore leachates, taking advantage of its strong partitioning across phases. In CO2 capture, its ability to bind and release gases repeatedly under mild conditions gives power plants a less energy-hungry carbon solution. On the analytical side, its solvating power supports advanced HPLC and SFC separations, especially for stubborn nonpolar organics or plant-derived oils. College teaching labs have started to include it in green chemistry courses, using it to demonstrate concepts of sustainable solvents and to move away from classic but toxic benzene-based experiments.

Research & Development

Many companies and academic labs tinker with the side chains on the imidazole ring, tweaking length and functional groups for specific reaction outcomes. Some add ether or nitrile groups, hoping for lower viscosity and faster mass transport. Teams working on renewable energy hope that pairing [PEIm][BF4] with solid-state electrolytes could open the door to more robust batteries at scale. Others look at functionalizing the cation to act as a chelating ligand, building complex multi-phase reaction cascades. Universities have established collaborative cross-disciplinary networks, blending organic synthesis, battery design, and computational simulations to push the field faster. A big driver of this research comes from global efforts to reduce hazardous solvent waste—every major chemical manufacturer now tracks solvent environmental footprints as closely as product yields.

Toxicity Research

Early hype sometimes missed the risks associated with ionic liquids. Over the years, thorough studies examined what happens when [PEIm][BF4] gets into soil or water. Results show moderate toxicity to aquatic life, mostly when concentrations exceed milligram-per-liter levels. Biological breakdown moves at a crawl; its persistent nature raises alarm over unchecked disposal. In vivo studies in rodents point to mild liver and kidney changes after large doses—enough evidence for regulators to demand careful waste disposal and handling. No major inhalation risk comes from its low volatility, but mouth or skin dosing can produce irritation and—at high enough exposure—systemic effects, especially in sensitive populations. Most of this toxicity traces back to the tetrafluoroborate anion, which can slowly liberate fluoride over time.

Future Prospects

With mounting global pressure to cut hazardous waste, [PEIm][BF4] sits in the crosshairs of regulatory bodies and innovation labs. Price for high-purity stocks still slows wide adoption in fine chemical and pharmaceutical production. Researchers are pushing synthetic methods that use renewable feedstocks, aiming to cut environmental impact from both manufacture and end-of-life. In energy storage, its nonflammable and stable nature could support the next leap in grid-level batteries, especially if ongoing tweaks can further widen the electrochemical window. Teams with access to powerful molecular modeling platforms are screening for new analogues with even lower toxicity but equivalent utility. Success in scaling, recycling, and green synthesis could one day make [PEIm][BF4] a mainstay—if the chemistry community stays alert to the double-edged sword of persistent synthetic molecules in our environment.

Why This Ionic Liquid Catches Attention

This molecule, known by those in chemistry circles as [PEIm][BF4], has been shaking up how people think about solvents. It belongs to the group called ionic liquids, which means it stays liquid at room temperature, doesn’t evaporate like acetone, and handles stubborn chemicals. The rise of green chemistry owes some of its spark to compounds like this one, which sidestep toxic solvents and bring sustainability a step closer to the lab bench.

Electrochemistry and Its Real Impact

In electrochemistry, familiarity grows around [PEIm][BF4] for its reliable performance. Many batteries and supercapacitors rely on stable, efficient electrolytes. This ionic liquid offers both high ionic conductivity and a wide electrochemical window, which lets devices run safely at higher voltages. That means better energy storage without frying the hardware. I’ve seen engineers get excited over tiny tweaks like this, since just one adjustment can stretch battery lifespans or help someone’s self-built solar charger run through harsher weather.

The semiconductor world also appreciates the chemical stability brought by compounds like this. Research in fuel cells and sensors keeps stretching the limits, and materials that don’t break down or poison the system have to step up. Using [PEIm][BF4], labs craft safer, longer-lasting prototypes. Researchers find themselves able to test for longer and push for new breakthroughs without hitting roadblocks caused by reactivity.

Solvent Power and Cleaner Processes

The first time I watched an extraction swap out a toxic organic solvent for an ionic liquid, the waste drum just about emptied itself. You notice straight away that emissions from these processes drop. Instead of breathing in harsh solvent fumes or struggling with messy cleanup, labs get a cleaner air and smoother workflow.

Industries handling pharmaceuticals or specialty chemicals look for the kind of precision [PEIm][BF4] brings. Separation tasks, like pulling out exactly the right ingredient from a mixture, turn more efficient. Less waste and lower risk mean safer workplaces and savings that trickle right down to the consumer. Some processes, like metal plating or rare earth extraction, relied heavily on harmful chemicals before researchers switched over to ionic liquids for selective extraction.

Environmental and Economic Wins

Ionic liquids promise less evaporation and reduced fire risk. In workshops and production lines, safety managers prefer them for obvious reasons. Fewer spills, less fire hazard, and real cost savings from not losing product to evaporation mean even small-scale operations get a boost.

Green chemistry brings responsibility into the lab and the factory floor. The environmental profile of [PEIm][BF4] sits in a better place than most competitors. Where laws and public opinion push for eco-friendlier solutions, this ionic liquid fits right in.

What Blocks Broader Adoption?

The main pushback? Production costs. Ionic liquids still demand complex setups to synthesize and purify. Scaling up usually runs into supply chain or technology hurdles. But with battery demands booming and emissions targets tightening, demand continues to surge. Researchers working together with manufacturers have started to find shortcuts and recycling methods to drive prices down.

Companies and labs willing to invest in smarter, safer technologies keep an eye on this space. As lower costs and wider knowledge come together, expect to see [PEIm][BF4] pop up in more places—from energy storage to greener synthesis—and bring chemical innovation home for good.

Digging Beneath the Chemical Name

Laboratories develop new chemicals all the time, and ionic liquids like 1-propyl-3-ethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate have shown up in recent years with great fanfare. They rarely evaporate, spark little fire risk and dissolve a lot of stuff regular water or oil can’t touch. They land in chemistry research, battery prototypes, and sometimes even green chemistry pitches. Cool credentials, but with a name like that, folks start asking: Will it hurt me? Will it hurt our planet?

The Science Behind the Label

1-Propyl-3-ethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate belongs to a family of salts that stay liquid at room temperature, not unlike their better-known cousin, table salt, but slippery and often colorless. These liquids can soak up ions, dissolve metals, and catalyze reactions that traditional solvents struggle with. Tetrafluoroborate acts as the counterion, keeping the mix neutral, while that odd imidazolium ring forms the core.

Digging into scientific data and chemical safety sheets, you spot some red flags. The boron-fluorine part (BF4−, as chemists say) doesn’t split up easily, and in water, it sometimes releases small amounts of hydrogen fluoride (HF). Ask any lab worker about HF, and their face tightens—a drop on the skin can trigger serious burns and eat through bone. That doesn’t mean this ionic liquid belches HF everywhere, but the risk hovers if things go south.

What About Touching or Breathing It?

Not much of this chemical drifts into air, so inhalation barely comes up. Touching the liquid is a different story; sometimes these ionic liquids soak through nitrile gloves, prickling skin or leaving chemical burns. Published studies point to low acute toxicity in animal testing, so gulping a mouthful won’t trigger instant collapse, but repeated exposure makes the story murkier—especially for those working long hours with it in close quarters.

Environmental Fate

Ionic liquids got popular partly because they don’t catch fire or vanish into clouds of vapors. But staying put doesn’t always mean safe. Once down a drain or into groundwater, this imidazolium compound lingers. Microbes struggle to break it down. Some studies flag aquatic toxicity: fish and water plants exposed to this family of chemicals show slowed growth, odd tissue damage, or even death if concentrations run high enough. And since these compounds resist natural breakdown, they stick around, building up over years.

Handling It Wisely

Wearing protective gloves and eye shields should not feel optional—even for experienced hands. Labs want closed systems and good ventilation. Spills need special cleaning powder, not a paper towel. Researchers have pushed regulators to study disposal of ionic liquids and create specific waste streams. Sadly, household or small-scale users rarely get that kind of guidance, so lots end up mixing it with regular trash or sewage, risking contamination downstream.

Moving Toward Solutions

Safer alternatives catch attention. Chemists explore new ionic liquids with biodegradable backbones and weaker halide counterions. Companies write safety policies from day one, not as an afterthought. And every researcher—from student to senior—learns that just because a chemical works doesn’t mean it can be rinsed down the drain.

Toxicity isn’t always dramatic. Sometimes, harm creeps in through little leaks, lingering in water, or through skin after a dozen careless exposures. Responsible handling, honest discussion, and smart design build trust—not just among scientists and regulators, but also communities who don’t want invisible hazards showing up in their rivers or food chain.

Looking Beyond a Simple Bottle on a Shelf

Too often, people see chemical storage as tossing whatever bottle into a cabinet. 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate, an ionic liquid, needs a little more thought. This isn’t table salt. Its unique mix of stability and sensitivity can be misleading, and a bad storage setup could mean ruined product, safety hazards, or faulty research results.

Moisture: The Quiet Threat in Most Labs

Many ionic liquids pull in water from the air. Over time, this downgrades their purity and messes with their performance in reactions. You can see it in the hazy results or the strange color shifts during use. Sealing this compound tightly, using air-tight bottles and even a layer of dry nitrogen, makes a big difference. I’ve dropped the ball on this with similar salts in my early years, and nothing ruins an experiment quicker than surprise hydrolysis.

Light and Temperature: Silent Compound Killers

A lot of people trust shelf life too much. Even stable ionic liquids like this one lose their punch under sunlight or in hot storage rooms. A dark storage space, preferably a chemical fridge hovering just above freezing but far from the frost line, gives peace of mind. Labs in humid regions feel this pain more. I learned from colleagues overseas who found sticky residues in their samples, all thanks to muggy nights and useless storage.

Container Quality: Cheap Plastics Don’t Cut It

Leaching and slow degradation sound like “future-you” problems. In reality, cheap containers just turn a valuable batch of chemical into unpredictable gunk. Glass with chemical-resistant stoppers, or certified polyethylene containers, set the baseline. I once used generic plastic, only to find the label peeling and the sample contaminated in a few weeks. The savings weren’t worth it.

Labeling and Documentation: Not Just Bureaucratic Hassle

Recognizing what sits in your storage is more than staying compliant. Mixing up compounds, especially similar-looking ones, leads to major setbacks. Date of opening, storage conditions, hazard symbols—all matter. I’ve seen researchers reach for the wrong bottle, thinking they saved time but actually doubling their workload after contamination.

Personal and Environmental Safety

People forget the waste angle. Ionic liquids often tout themselves as “green,” but improper disposal or leaks tell a different story. Secondary containment, working away from drains, and clear protocols minimize long-term headaches. A spill kit nearby saves not just money but health.

Improving Storage for Lab Longevity

Good storage starts with a culture of respect for chemicals. Training lab members, auditing inventory, and keeping up with safety data sheets all factor into sustainable use. Automated environmental monitors—humidity, temperature, and light alarms—help busy teams avoid losses.

Wrapping Up Storage Realities

Storing 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate safely isn’t just about following a checklist. Tight seals, dark and cool conditions, quality containers, careful labeling, and strict waste management create a safer lab and better research. Each small step protects investments, health, and the environment.

Unpacking the Purity Concerns

Every time I’ve ordered a specialty ionic liquid like 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate from a chemical supplier, the same question circles back: “How pure is this batch, really?” On paper, many commercial products sport a purity of 98% or even higher. Yet in any research lab, one percent can turn the tide. That sliver could be water, unreacted imidazole, residual solvents, or even decomposition products. Each of these brings noise to the experiment. I remember wasting weeks on an electrochemical study before finding that a trace contaminant in the ionic liquid had been quietly torpedoing my results.

Manufacturing Realities

Most producers rely on rigorous processes: high-grade starting materials, advanced purification techniques, and regular testing. In the real world, though, small-batch synthesis often feeds the market. It’s not just the synthesis stage that matters — how the product gets handled post-purification has its own story. Moisture and light can creep in if vials get opened often. Polytetrafluoroethylene-lined caps and amber bottles help, but not every supplier takes that extra care at every step.

GC-MS, NMR, or HPLC analyses often accompany commercial lots of 1-Propyl-3-Ethylimidazolium Tetrafluoroborate. If a lab receives a batch without a recent chromatogram or a detailed impurity profile, it’s wise to ask for it. In my own group, we once found significant chloride contamination—way above the supplier spec—simply because storage protocols slipped at the warehouse.

Impact on Real Experiments

The problem becomes obvious once an ionic liquid that’s supposed to boost conductivity instead clogs up your electrode. Even a smidge of extra water changes viscosity, shifts solubility, or flips selectivity in catalysis work. Impurities that seem too minor to matter can unravel experiments built on precise chemical balance. It’s not just academic curiosity: in battery development, small impurities act as silent saboteurs, gutting cycle life or yielding misleading performance data.

Published papers rarely mention struggles with commercial chemical quality, but anyone who regularly handles ionic liquids can tell story after story. Real-world testing actually starts after the reagent arrives. Drying over phosphorus pentoxide, running Karl Fischer titrations, or redistilling from potassium carbonate becomes routine for groups that value reproducible results.

Toward Better Quality

What improves reliability is transparency from chemical suppliers. Some now include detailed water content and halide analysis, stress-tested against conditions closer to actual use. Researchers also benefit when vendors open their doors for scrutiny—welcoming independent quality audits, or working with labs to develop custom purification steps.

For those starting out, basic validation makes a world of difference. Always check the COA and ask pointed questions about trace ions and residual solvents. Setting up a few simple quality tests in-house, even if that’s a single NMR run or a trial reaction prone to sabotage by water, can highlight unseen risks before a whole project rides on an impurity.

Purity looks great on a label, but reliability shows up in experiments that consistently work. The more demand there is for transparency and proof, the better for both the chemistry and everyone depending on its success.

A Look at Melting Point and Its Value for Chemists

I’ve always been struck by how the melting point of a substance can tell you so much about what it can do in the lab. With 1-propyl-3-ethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, the melting point lands comfortably below room temperature—right around 6 degrees Celsius, give or take a degree or two, depending on the exact conditions. This means it tends to stay liquid unless you’re working in a really chilly environment, which opens the door for it to act as a solvent in all sorts of interesting scenarios. No need for special equipment to keep it fluid in most climate-controlled labs, which saves resources.

Organic liquids with low melting points like this one can be handled with standard glassware and simple heating devices. I’ve worked with ionic liquids in grad school, and I always appreciated not wrestling with solid chunks or clumps when measuring out what I needed. Being a liquid at room temperature helps keep things simple and consistent.

Solubility: Water-Friendly and Beyond

Solubility always matters if you want to avoid layers or sludge at the bottom of a flask. This ionic liquid dissolves pretty well in water, which honestly surprised me at first, considering that some similar salts hardly budge in water. Its solubility in water shows up as miscible—meaning it mixes in any proportion, no phase separation or cloudiness. That plays a huge role if your reactions or separations need compatibility with aqueous solutions.

What about mixing with organic solvents? I’ve found that imidazolium-based ionic liquids often blend comfortably with polar organics like methanol or acetonitrile but tend to steer clear of non-polar ones such as hexane. If your workflow leans toward polar reaction media, this property provides some flexibility.

Staying Stable: Why It Matters for Real Applications

Ionic liquids get a lot of attention in research circles for their ability to stay stable over a range of temperatures, moisture, and even air exposure. Tetrafluoroborate, as the anion, usually helps deliver that stability. I remember a project where we stored a sample on a shelf for weeks without obvious change. You don’t have to worry about it evaporating or decomposing under standard conditions, a big plus compared to more volatile solvents.

Any chemist facing scale-up has probably run into the headache of solvent recovery and safety. Low volatility for this ionic liquid means lower risk of inhalation and less loss to evaporation. The tetrafluoroborate part keeps it from picking up water from the air and turning into a sticky mess, making cleanup easier and keeping equipment in better shape over time.

Pushing Toward Greener Chemistry

Many scientists look for ways to reduce waste and avoid dangerous fumes. This compound fits that trend. Less evaporation, less odor, and fewer handling hazards matter when you’re spending hours in a lab. Tetrafluoroborate-based ionic liquids, like the propyl-ethylimidazolium variety, have helped streamline extraction processes where water or volatile organic solvents might fall short. I’ve used ionic liquids to pull metal ions from wastewater and noticed not only efficiency but also reduced secondary pollution.

There’s always room to push for more data, especially about long-term environmental effects and recycling after use. But at the bench, the physical properties make this ionic liquid a practical, greener alternative for extractions, separations, and sometimes even as a reaction medium itself.