1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate: From Lab Bench Curiosity to Industrial Relevance

Historical Development

Chemists started to tinker with ionic liquids in the late 20th century, chasing greener and more efficient ways to replace traditional solvents. 1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate came along as researchers looked for ways to use imidazolium-based ionic liquids with less environmental baggage. Its story grew out of the search for solvents that don’t evaporate at standard conditions and that show off unique chemical features. Researchers found that pairing 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium cations with dihydrogen phosphate anions opened new doors in both synthesis and separation science. Over a few decades, this compound shifted from being a lab curiosity to an important ingredient in electrochemistry, catalysis, and materials fabrication.

Product Overview

This chemical lands in the ionic liquid family—salts that melt below 100 °C and stay liquid at room temperature. Its core structure connects a propyl chain and a methyl group to an imidazolium ring, matched with the dihydrogen phosphate anion. This combination gives the compound high thermal stability, low vapor pressure, and strong ion conductivity. In my own work with sustainable solvents, I kept coming back to this family because they can dissolve a broad range of organic, inorganic, and even some biological materials, without releasing a cloud of volatile organics. So, for labs keen on reducing solvent-related emissions, this one stands out.

Physical & Chemical Properties

1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate forms a viscous, colorless-to-yellowish liquid at room temperature. Its density sits higher than most standard organic solvents, which often changes how samples layer or mix during extraction. Conductivity measures in the range needed for practical battery electrolytes. Solubility reveals another story: it dissolves well in water, but mixes less with nonpolar solvents. It also refuses to catch fire, which brings peace of mind to busy labs. Its thermal stability holds up well to strong heating, often withstanding more than 250 °C before notable decomposition sets in. Testing its acidity, the solution leans mildly acidic because of the dihydrogen phosphate, yet not so harsh as to corrode glassware or skin on contact.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Manufacturers list this chemical by the formula C7H15N2O4P, often sold at greater than 97% purity for research and industry. Typical bottles come with hazard warnings about skin and eye irritation, details on safe storage at room temperature, and clear expiration dates, since moisture can sneak in and change its properties. Labels note its CAS number, batch, and often the presence of any residual water. Transport guidelines follow standard rules for non-volatile chemicals, though labs need secondary containment to prevent leaks or spills.

Preparation Method

Synthesizing 1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate usually begins with quaternizing 1-methylimidazole using 1-bromopropane under controlled conditions. The resulting bromide salt gets purified before swapping the bromide for dihydrogen phosphate through anion exchange, often by reaction with silver dihydrogen phosphate or direct acid treatment. Recrystallization or vacuum distillation steps clean up the product, but workers in synthetic labs also dry the liquid under vacuum to strip out any traces of water. I’ve seen small-batch syntheses that run on the benchtop in glass reactors, and bulk processes scaling up in stainless steel—both need careful temperature and addition rates to keep the reaction mixture smooth.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

This ionic liquid steps up as a reaction medium for organic and inorganic transformations that need strong solvation but low volatility. For esterifications, transesterifications or acid-catalyzed reactions, it supports decent yields and often allows easier product isolation after the main step finishes. It solves transition-metal catalysts well and sometimes stabilizes sensitive intermediates, a fact not lost on those working in pharmaceutical or fine chemical synthesis. Chemical modification of the parent compound hinges on swapping the alkyl groups or the anion; even a small change can shift its hydrophobicity or melting point dramatically, which tailors the property set for each job.

Synonyms & Product Names

The most common synonyms are [PMIM][H2PO4], Propylmethylimidazolium dihydrogenphosphate, or 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium phosphate. Product catalogs show it listed with these names, and researchers often shorthand it as "PMIM DHP" in technical papers. Brand names rarely deviate, since suppliers want clarity in regulatory filings and chemical registries.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling this compound feels much safer than using volatile organics, yet gloves and splash goggles don’t leave the bench. Skin contact may tingle or redden but rarely burns outright—still, repeated exposure dries the skin, so a good barrier cream pays off. This chemical doesn’t fume or threaten with inhalation, but spills on lab benches stay sticky and tricky to clean if left to dry. Storage in sealed glass or high-density polyethylene bottles keeps it from soaking up moisture and helps contain any drips. Spills wash up with water, though in larger settings, absorbent pads and proper chemical waste tags cover the regulatory bases. Safety data sheets echo these points, flagging medium-level hazards and straightforward cleanup.

Application Area

Pulse research on ionic liquids into batteries, fuel cells, CO2 capture, and biocatalysis, and this particular compound shows up again and again. In one project to build safer proton exchange membranes, I mixed PMIM DHP with polymers. The blend delivers high ion conductivity under low humidity, which old-school materials couldn’t touch. In biochemistry labs, this chemical dissolves cellulose and starch, letting enzymes or catalysts reach target sites fast. Engineers also pump it through test rigs for lubrication, antistatic agents, or separation of rare earth metals. Its broad window of stability and low flammability win it slots in pilot plants pushing for green chemistry upgrades without gutting existing hardware.

Research & Development

Grant proposals still pour in to test new roles for imidazolium dihydrogen phosphates. Researchers want to know how the cation chain length or anion tweaks change recyclability in real-world devices. My own reading scans studies that tackle deep eutectic mixtures—by blending this solvent with other ionic liquids or cosolvents, new phases emerge for biomass pretreatment, pharmaceutical crystallization, and advanced coatings. R&D teams at academic and corporate levels check thermal performance, ion mobility, and resistance to fouling. The hunt continues for non-toxic, easily recycled versions, often through replacing part of the structure or shifting away from phosphorus-based anions for lighter environmental impact.

Toxicity Research

Toxicity tests rarely show major alarm bells for this compound, especially compared to classic volatile organic solvents. Acute readings in aquatic life show lower effects, though long-term or chronic exposure still calls for caution. Testing in rat models with doses much higher than would occur in ordinary handling gives mild adverse effects but nothing catastrophic. In my own routines, lab hygiene keeps possible chronic effects away—no food, drink, or bare hands in reach when this liquid comes out. As one advances into scale-up or disposal, the spent solution needs neutralization before entering waste streams to avoid trace phosphate buildup. Regulatory outlook keeps evolving, but right now, the safety footprint compares favorably to legacy acids or alkylphosphates.

Future Prospects

Walk through today’s chemical and energy research, and ionic liquids stay in the spotlight. 1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate carries the potential for safer, more sustainable manufacturing, especially as climate and emissions rules ramp up. Teams in materials science look to ionic liquids for 3D printing, biomedical coatings, and even solar cell electrolytes. One real advantage is the ability to recycle and regenerate these liquids after use, reducing both material costs and waste streams—provided separation techniques keep improving. Cutting down both the toxicity and phosphorus reliance would extend utility further, opening replacement of petrochemical solvents in even more sectors. The future for this chemical hinges on tuning the structure for targeted reactivity and easier recovery, guided by both environmental necessity and the need for fresh technical breakthroughs.

Digging into Its Story in the Lab

Scientists have given many ionic liquids odd names, but 1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate pops up a bit more often in chemistry discussions. If you’ve ever tried to break down cellulose or thought about green chemistry, you’ve probably seen this name on a bottle or two. Labs keep reaching for it not because it sounds exotic, but because it helps where regular solvents fail or make too much mess.

Turning Forest Waste into Something Fresh

Paper and pulp companies spend tons of money handling plant waste. Turning all that lignocellulose into usable stuff still takes too much energy and water. Researchers noticed that 1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate (some shorten it to [PMIM][DHP]) breaks down those tough plant fibers without needing enormous heat or crushing force. The result is cleaner sugar extraction or biofuel production, using fewer harsh chemicals.

Less Useless Gunk, Fewer Headaches

Most of my time near beakers ends with sticky leftovers or annoying by-products. Some solvents fill the air with fumes that leave you with a headache after a day in the lab. This phosphate-based ionic liquid doesn’t evaporate much and smells less than what’s usually sitting in chemical stores. You can wash it out with water, and it can be recovered for another round, which saves both money and the environment.

Green Chemistry: Not Just Buzzwords

University groups and companies—including a few in process engineering—started pushing [PMIM][DHP] because it fits the “green solvent” bill. Regular organic solvents often ignite, make poor air or even damage lab equipment over time. This liquid doesn’t catch fire easily and keeps its structure even at higher heat levels, making work safer for everyone. Production chains in both textiles and pharmaceuticals now see this as a real alternative. Less hazardous waste means less regulatory headache, too.

Fighting Back Against Microbes

People in pharmaceuticals chase new ways to knock out microbes without contributing to antibiotic resistance. Some medical researchers looked into [PMIM][DHP] and spotted mild antibacterial activity. While it doesn’t replace classic drugs for now, adding it to packaging or medical coatings could keep germs at bay and extend shelf-life for products that don’t play well with moisture. Food-tech teams even tried it as an additive for this reason.

Challenges and Some Fixes on the Horizon

There’s no magic bullet in chemistry, and this liquid isn’t perfect. Large runs still cost a fair bit, and making it in huge batches takes careful handling. Wastewater treatment facilities aren’t always set up to handle ionic liquids. Research groups suggest building better recycling systems in labs and scaling up green production methods, such as continuous-flow reactors or closed-loop cycles. Some manufacturers started investing in raw materials that don’t depend on fossil sources, which could cut its carbon footprint.

Putting Money and Hope on the Table

Even a few years ago, “green” chemicals got lots of talk and little funding. With new sustainability goals and stricter laws around chemical waste, labs and industry leaders now gamble real money on ionic liquids like [PMIM][DHP]. The success of this solvent depends not just on what it can dissolve, but how responsibly it gets produced and reused. Advanced materials—and all those future tech promises—sometimes lean on a single, well-chosen liquid. From what I’ve seen, this one earns its spot on the shelf for researchers who really want to change the game.

Getting to Know the Substance

Anyone working in a lab long enough runs into a long list of chemicals with complicated names. 1-Propyl-3-methylimidazolium dihydrogen phosphate joins the growing family of ionic liquids, a group often celebrated for their low volatility and potential as “green” solvents. Yet, as with any chemical, a fancy reputation never guarantees safety in the hands of a researcher, technician, or factory worker.

Looking at Health Risks

Researchers have looked at the toxicity of various imidazolium-based ionic liquids. Some show irritation to skin and eyes, and a few cause problems when inhaled or ingested. The 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium cation isn’t the most toxic member of the group, but that’s not a green light for sloppy handling. Skin contact can still lead to redness, and it’s tough to predict who will have a stronger reaction. Ingestion brings its own dangers, with gastrointestinal discomfort reported in some cases. My own time around imidazolium salts taught me to wear gloves every single time, even for quick weighing or transfers.

Environmental Concerns

Marketed as alternatives to organic solvents, ionic liquids seemed like a gift to chemists hoping to cut back on volatile organics. But this same lack of evaporation means spills don’t just float away on a breeze. Once in the sink or down a drain, these compounds can end up in waterways. Studies show that some ionic liquids linger in the environment and show moderate toxicity to aquatic life. I’ve often watched colleagues, pressed on time, rinse out flasks and let residues wash down the drain. That’s not smart—especially for anything persistent or bioactive.

Common-Sense Safety Practices

A chemical’s safety starts with respect—and the basics pay off. Gloves and goggles act as the first line of protection. Lab ventilation goes a long way in reducing airborne traces. It’s a mistake to assume that “non-volatile” means “harmless.” Spills need clean-up kits and prompt attention. I always keep a spill kit handy when working with any new compound. For disposal, collecting waste in separate, clearly labeled containers avoids accidental reactions or illegal dumping down the drain.

Training and Documentation Matter

Experience shows gaps in safety training make for accidents. Clear, up-to-date material safety data sheets (MSDS) help. Everyone handling this ionic liquid should see the hazard ratings and recommended precautions. New lab members learn by watching, but they also need reminders—posted signs at the bench or sink help prompt better habits. The best labs I’ve worked in made training routine, not a one-off event.

Possible Solutions and Responsible Handling

Sourcing chemicals from suppliers who offer tested, well-documented products helps reduce risks. Encouraging research into more biodegradable alternatives keeps the field moving forward. Some labs now monitor effluent carefully, treating waste before it leaves the building. These steps keep not just workers but whole communities safer. For a chemical like 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium dihydrogen phosphate, balancing innovative uses with real safety keeps progress on solid ground.

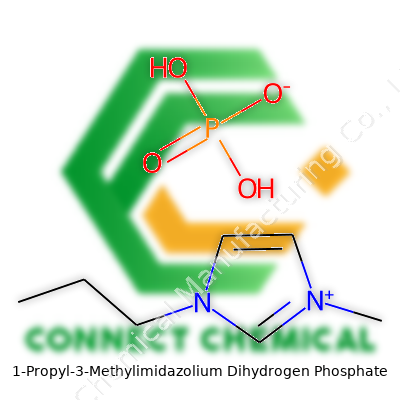

The Formula: C7H15N2O4P

Talking about ionic liquids, the name 1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium Dihydrogen Phosphate often shows up. The chemical formula, C7H15N2O4P, seems like a jumble at first glance. If you look closer, though, there's plenty going on behind each letter and number. C7H15N2O4P tells you there are seven carbons, fifteen hydrogens, two nitrogens, four oxygens, and one phosphorus atom packed inside each molecule. This compound stands as an example of how chemistry can shape cleaner technologies, better batteries, and greener industries.

What the Formula Teaches

I remember grinding through chemistry in college, rolling my eyes every time a formula popped up on the board. After a while, these letters turned from a random sequence into stories about the way molecules behave. In this case, C7H15N2O4P supplies us with a cation that is basically an imidazolium ring with propyl and methyl groups stuck to it. The anion part—dihydrogen phosphate—brings in not just balance, but properties that encourage strong interaction with water and hydrogen bonds.

C7H15N2O4P shows up in labs around the world because of its reputation as a low-volatility, thermally stable ionic liquid. It does not easily evaporate, making it safer to handle than many volatile organic solvents. Types like this are earning more attention as scientists turn away from solvents that pollute and linger in the environment.

Why It Matters in the Real World

Switching old industry habits takes something tangible—like a liquid that works just as well without the fumes. Ionic liquids with 1-Propyl-3-Methylimidazolium cations and dihydrogen phosphate anions fill that spot. The chemical formula means nothing unless it brings real results. Research shows these liquids handle cellulose well, helping break down plant fibers that could replace plastics or become renewable fuels.

As industries try to shrink their environmental footprint, more of them turn to compounds like this one. For example, the C7H15N2O4P molecule dissolves certain kinds of biomass without the need for explosive or toxic additives. It's getting easier to imagine a time where instead of barrels of traditional chemicals, factories start with safer, non-volatile liquids that make less mess to clean up.

Challenges and Next Steps

People sometimes worry about the cost or the unknown risks of brand-new chemicals. No one should ignore those. Some ionic liquids end up being expensive, and researchers need clear ways to predict their effects on ecosystems before rolling them out. The best way around those hiccups comes with open data, tight safety standards, and governments backing green chemistry.

Producing and testing C7H15N2O4P on a large scale brings out lessons few can learn in book chapters alone. Scientists often share their findings in open journals, letting others test ingredients and tweak processes. Quality research looks at biodegradability, effectiveness, and cost—topics that affect real decisions on whether this formula finds a home in new products.

At the end of the day, C7H15N2O4P shows how chemistry can steer the wider transition to cleaner living and sustainable industry. That formula means more than a label; it flags a shift toward safer, smarter ways to run factories, labs, and even homes that think ahead for the next generation.

Day-to-Day Handling of a Sensitive Chemical

Dealing with 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium dihydrogen phosphate in a real-world setting takes more than reading a datasheet and calling it a day. A bottle of this ionic liquid can’t just be left on the nearest shelf. Over the years, too many labs ignore storage rules, only to see containers end up sticky, contaminated, or downright hazardous. Watching this stuff turn brown at the edges or pick up water like it’s a sponge brings home why careful storage matters.

Stability Rests on Basic Storage Choices

Strong air exposure, high heat, and stray moisture—these pile up as risk factors for any ionic liquid, and this one is no different. Most seasoned chemists stick these bottles in a dry, cool store room, away from windows and steam pipes. I’ve seen colleagues forget, with labels peeling and caps crusted over. The purity tanks, and so does the trust in your experiments.

Humidity turns this chemical into a headache fast. I once worked in a lab where the desiccator got overlooked between deliveries, and whole batches had to be tossed. A dry atmosphere, with a proper desiccant, protects both your research and your safety. A sealed glass or compatible plastic container—preferably amber to knock back light exposure—always wins over open beakers and reused jars.

Keeping Safety Front and Center

Many researchers find these ionic liquids less risky than solvents that burn or catch fire, but it’s easy to develop a false sense of security. Spills and accidental contact still cause real harm. If you store it close to acids or oxidizers, trouble multiplies. I made the mistake of stacking incompatible materials in a cramped storage area early in my career—it taught me how quickly a small oversight becomes a major problem.

Storing chemicals should never feel routine enough to get sloppy. Labels need to be clear and legible. Gloves and goggles mean fewer accidents, and in a shared workspace, everyone has to pay attention so one person’s mess doesn’t become everyone’s problem.

Long-Term Preservation and Accountability

Beyond protecting your own work, proper storage shows respect for the team. When containers leak or start to break down—sometimes thanks to cheap plastics—everything nearby risks contamination. For long-term use, glass with airtight seals pays off. It lets the liquid keep its color and keeps out whatever’s floating in the air.

Inventory logs can sound like bureaucracy, but real records catch mistakes before they spread. I’ve seen labs lose hours to hunting down mislabeled chemistry, or swapping out entire sets of reagents because someone guessed and got it wrong. The best teams have a “date received” and “date opened” right on the label.

Room to Improve: Training and Facility Design

Training isn’t just for newcomers. Even those with years on the job need refreshers on storage rules. Peer review and regular walk-throughs catch problems early. Better air quality, moisture controls, and clearly marked safe areas shift chemical storage from an afterthought to a priority. Good habits, more than fancy systems, keep people and substances safe year in and year out.

Understanding the Basics

1-Propyl-3-methylimidazolium dihydrogen phosphate stands out among the ever-growing list of ionic liquids showing promise beyond academic curiosity. This salt, built around an imidazolium ring and a phosphate counterion, walks the line between solid-like structure and the easy-flowing movement common to liquids. Most folks working in chemistry or energy storage start to recognize the value of such substances for their fluidity, thermal stability, and their quirks under the microscope.

What Shows Up in the Lab

Talking about appearance, you see a clear or very pale yellow liquid at room temperature. It pours much thicker than water. Measuring viscosity, you find numbers shooting well above what you’d get with ethanol or acetone. That’s partly due to the ionic nature—cations and anions, strong attractions, not many ways for the molecules to zip past each other. A stirring rod moves slowly, and you know right away you’re working with something outside the everyday world of solvents.

Boiling it doesn’t make sense for most experiments, since decomposition tends to happen long before you hit anything like the boiling point of water. Thermal gravimetric analysis usually shows this liquid sticking around up to roughly 200–250°C before breaking down into something no longer useful. In my own lab shelf, accidentally heating this too far meant smelling sharp, acidic vapors—a quick signal you’ve crossed a line. Freezing is also uncommon under normal bench conditions. The specific melting point might land around 15–20°C, meaning cold rooms or winter mornings can push it toward a glassy or hardened slug, but in most labs it stays pourable most of the year.

Hydrogen Bonding and Water

This compound loves water. Its phosphate anion pulls in moisture from the air. Sitting open to the atmosphere, you’ll end up with a heavier, more diluted liquid—sometimes a minor shift in mass, sometimes a real headache for someone looking for tight purity in their measurements. That affinity lets it blend with water and hydrophilic solvents easily, much more so than hydrophobic ionic liquids, opening up greener options for extraction or as reaction media.

Electrical Conductivity and Applications

Imidazolium ionic liquids catch attention partly for their ability to carry electric current, even without added salt. This compound conducts better than most oils or glycols, but not as freely as simple acids or salt solutions. Lab readings for conductivity often land between 1–10 mS/cm at room temperature. Such numbers suit it for electrochemical cells or as a part of electrolyte blends. Countless researchers, myself included, have run basic aluminum corrosion and see this type of ionic liquid resist the worst pitting and wear, likely due to its stable hydrogen phosphate backbone.

Challenges and Paths Forward

Handling and storing this substance goes smoother in low-humidity rooms. Anyone who’s spilled a bit on scales or benchtops knows how sticky and persistent these films become. The solution often comes down to proper sealing and silica gel in storage containers. That said, the growing toolbox of ionic liquids like 1-propyl-3-methylimidazolium dihydrogen phosphate calls for stronger researcher training, clear datasheets, and industry guides. Green chemistry circles aim for even lower toxicity, lower cost options, but seeing this molecule in your own hands, its usefulness feels immediate and practical for the right niche.